Source: Link

Lindsay (Lindsey, Linzy, Linsday), John Washington, abolitionist, blacksmith, businessman, and community activist; b. c. 1805 in Washington, D.C.; m. Harriet E. Hunter in St Catharines, Upper Canada (the marriage licence is dated 4 Aug. 1840), and they had nine children, of whom six survived to adulthood; d. 31 Jan. 1876 in St Catharines, Ont.

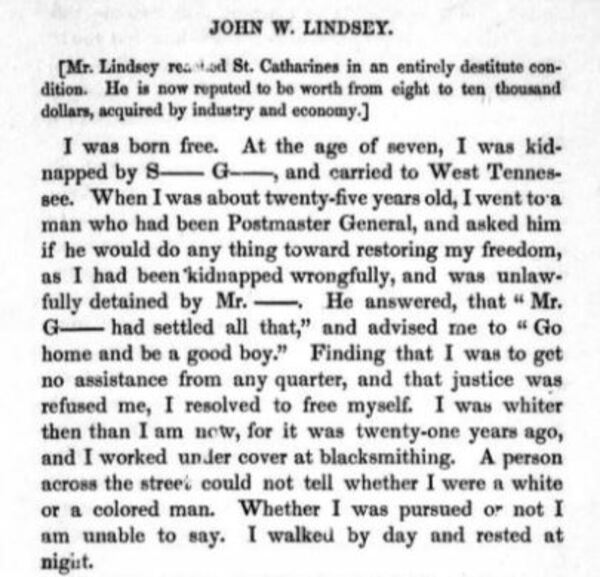

Sometime around 1805 John W. Lindsay was born into a free Black family in the newly established capital city of the United States. When he was seven, slave catchers abducted him; he would later assert that “a great many colored people who were free born have been kidnapped.” Taken to South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama, he eventually found himself in western Tennessee. There, aged about 30, he came to a profound decision after an attempt to assert his right to liberty was rebuffed: “Justice was refused me, I resolved to free myself.” Escaping bondage, he considered returning home to find his parents, but learning that the American capital remained a dangerous place for Black people, he headed to British Canada. In order to receive the rights granted to natural-born white men by the United States constitution, he had to flee his native land.

Since he was light complected and spoke “in so important a way” (not using the deep Black vernacular associated with enslaved people), Lindsay had “little difficulty,” he said, in reaching the borderland town of St Catharines, where he had settled by 1835. There he joined a small Black population in the Niagara region, whose presence dated from the arrival, after the American Revolutionary War, of Black loyalists [see Richard Pierpoint*] and the slaves of white loyalists. He made his home in the “Colored Village,” where most of the town’s Black settlers lived. According to the Reverend Hiram Wilson, an abolitionist missionary, he arrived penniless but by 1854 had become the wealthiest person in the Black community. In 1842, using the name John Washington Linzy, he applied for naturalization as a British subject, and he officially obtained it on 10 June 1844. In contrast to the majority of Black residents, and many whites as well, he was able to sign his name.

The industrious Lindsay worked as a labourer, farmer, pedlar, and blacksmith. He had learned blacksmithing in the American South, and he promoted economic growth in his Canadian community by instructing others in the trade. Finding that “the colored people in Canada … are barred out from every thing that will give them a living,” he also promoted Black self-sufficiency or, as he phrased it, making “business within ourselves.” He managed to establish several ventures, including a grocery store and a beer company, that catered to the Black community. Between 1854 and 1876 the value of his taxable property grew from some $575 to over $6,000. In 1863 he would tell the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission (AFIC), which took evidence in Upper Canada, that he had “got along astonishingly well, considering there was so much prejudice.” He rented out many of his properties, showing no bias as to occupation, age, gender, or colour. He met and married Harriet Hunter of Cincinnati, Ohio, in St Catharines. Educated in her home state at Oberlin College, she had arrived in Upper Canada in 1839 as a teacher, under Hiram Wilson’s auspices. She was Lindsay’s companion for over 35 years and played an important role in his business success.

Lindsay was deeply involved in the community, in the affairs particularly of the Black residents, who by the time of the 1861 census numbered more than 600 (in a total population of some 6,200). His standing would come to rival that of other Black Canadian leaders, such as Harriet Tubman [Ross*], Wilson Ruffin Abbott, and Mary Ann Camberton Cary [Shadd*]. From the time of his arrival, he was a noted figure in the annual August First Day celebration of the date in 1834 when Britain’s Slavery Abolition Act came into force. He belonged, as did Tubman (a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad), to two local interracial organizations, the Refugee Slaves’ Friends Society and the Fugitive Aid Society of St Catharines. During the 1850s, as a long-standing trustee of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (from 1856 the British Methodist Episcopal Church [see Richard Randolph Disney*]), he played a key role in funding and building Salem Chapel. In the same decade he worked to settle the affairs of a failed Black settlement in Dawn Township [see Josiah Henson*]. During elections he publicly supported those he believed would advance the interests of Black residents, his influence ensuring that these candidates had the Black voting bloc.

During the American Civil War from 1861 to 1865, Lindsay followed the conflict’s developments and continued to help fugitive slaves settle on Canadian soil. After the Emancipation Proclamation came into effect in 1863, many Black people in Upper Canada returned to the United States, but he decided to stay in a country that he felt offered him greater opportunities, despite the discrimination his community faced. “I find the prejudice here the same as in the States. I don’t find any difference at all,” he told the AFIC. “Very often, when a colored man goes to a farmer for work, he will not take him, though he may want help ever so bad, because he won’t condescend to have him about his house.… A man, you know, cannot help his skin.” Still, he thought that “perhaps God means to bring good out of this great war.” He understood that Canada and the United States were interconnected and that the eradication of bondage south of the border would benefit Black residents to the north.

The segregation of education in St Catharines was a long-standing issue for Lindsay. Throughout the 1850s and 1860s there was only one school that Black children, “from one end of the town to the other,” could attend, and it was not as well funded as other schools. “Here are our children, that we think as much of as white people think of theirs, and want them elevated and educated,” he said to the AFIC, “but … I have never seen a scholar made here [St Catharines] amongst the colored people.” In 1871 he spoke out about educational injustice and signed a petition asking that Black children be permitted to go to schools in the wards in which they lived. The successful conclusion that year of a court case brought by labourer William Hutchinson, whose son had been denied entry to a white school, effectively desegregated education in St Catharines.

In addition to supporting Black youth, Lindsay took an interest in the senior members of his community and sought to ensure that they were properly housed. In 1868 he had pleaded before the municipal council for an aged woman in need, and he provided living quarters in his rental properties for two elderly widows. He remained active to the end. In 1873 he led the August First Day parade as a marshal, and the following year, still advocating for his community, he requested that sidewalks be constructed on Geneva Street, which served as a main street for the Black population. After falling ill in 1875, he spent four months under the care of leading local physician Lucius Sterne Oille before dying of hypertrophy on 31 Jan. 1876. He was interred in Victoria Lawn Cemetery two days later. In his will, drawn up shortly before his death, he left his wife a substantial estate. Harriet Lindsay would die of paralysis on 28 March 1881.

Lindsay made a number of interesting contacts during his Canadian years. He was interviewed by Boston abolitionist Benjamin Drew in 1855 and by the AFIC’s Samuel Gridley Howe in 1863. On good terms with local politicians, he may also have become acquainted with journalist Samuel Ringgold Ward*, who visited St Catharines in 1853, as well as with American abolitionists Frederick Douglass and Jermain Wesley Loguen, who lectured in St Catharines on occasion. In 1860, at the one white-organized social event – a Conservative Party banquet – he was asked to attend (“as a general thing, the colored people are not invited into society,” he noted), he met the attorney general of Upper Canada, John A. Macdonald*, the future first prime minister of Canada.

John Washington Lindsay had an eventful life, rising from the injustice of bondage to enjoy a position of relative affluence and influence. The most remarkable thing about his story, however, is that his success was achieved in Canada. He had, after all, been born free in the capital of the United States of America.

In 2023 John Washington Lindsay’s badly broken grave marker was uncovered and reassembled by the Salem Chapel Underground Railroad Cemetery Project.

Lindsay’s interview with Benjamin Drew is found in Benjamin Drew, The refugee: or the narratives of fugitive slaves in Canada … (Boston and Cleveland, Ohio, 1856; another edition, The refugee: narratives of fugitive slaves in Canada, intro. G. E. Clarke (Toronto, 2008)). His testimony before the American Freedman’s Inquiry Commission appears in Slave testimony: two centuries of letters, speeches, interviews, and autobiographies, ed. J. W. Blassingame (Baton Rouge, La, 1977). The other sources for his life are detailed in the author’s “‘Justice was refused me, I resolved to free myself’: John W. Lindsay finding elements of American freedoms in British Canada, 1805–1876,” Ontario Hist. (Toronto), 109 (2017): 27–59; and Borderland Blacks: two cities in the Niagara region during the final decades of slavery (Baton Rouge, 2022).

Cite This Article

Dann J. Broyld, “LINDSAY (Lindsey, Linzy, Linsday), JOHN WASHINGTON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lindsay_john_washington_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lindsay_john_washington_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Dann J. Broyld |

| Title of Article: | LINDSAY (Lindsey, Linzy, Linsday), JOHN WASHINGTON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |