Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

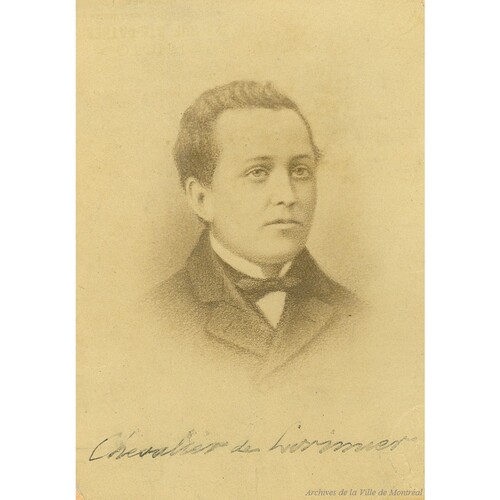

LORIMIER, CHEVALIER DE (baptized François-Marie-Thomas, he later received the given name Chevalier, apparently from his uncle and godfather François-Chevalier de Lorimier; generally referred to as François-Marie-Thomas-Chevalier de Lorimier, he always signed Chevalier de Lorimier), notary and Patriote; b. 27 Dec. 1803 in Saint-Cuthbert, Lower Canada, third of the ten children of Guillaume-Verneuil de Lorimier, a farmer, and Marguerite-Adélaïde Perrault; d. 15 Feb. 1839 in Montreal.

Chevalier de Lorimier was a descendant of an old family of French nobility which had remained in New France after the conquest and whose decline led its members to seek integration into the rising Canadian bourgeoisie in the 19th century. It is not known when his parents came to live in Montreal, but it is certain that in 1813 young Chevalier began his classical studies at the Petit Séminaire de Montréal. At the time he finished these in 1820, he evidently had not yet chosen a profession, since he did not begin articling under Pierre Ritchot, a Montreal notary, until three years later. During his period of training he became friends with his employer.

In his political testament Lorimier noted that he had become active in politics as early as 1821 or 1822, when he was 17 or 18 years old. An idealist enamoured of liberty and drawn from the outset to the national cause, he was one of a group of young men who early became involved in the struggles that Louis-Joseph Papineau* and his supporters were waging against the governor, Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay], and the Executive and Legislative councils of Lower Canada. Lorimier in all likelihood participated in the vast campaign organized in 1822 to protest against the plan to unite Lower and Upper Canada [see Denis-Benjamin Viger*]. In December 1827, when the conflict between the governor and the House of Assembly had entered an extremely tense phase, he signed a petition from the inhabitants of Montreal County to King George IV that among other things condemned the “arbitrary and despotic” conduct of Dalhousie and asked for his recall, denounced the pluralism engaged in by a small group of privileged individuals, and requested an enlarged number of seats in the assembly proportional to the increased population of Lower Canada.

Lorimier was commissioned to practise as a notary on 25 Aug. 1829 and drew up his first instrument on 6 September. A fortnight later he set up his office in a house in the faubourg Saint-Antoine, probably not far from the home in which his parents had resided since at least 1819. Subsequently he went into partnership with Ritchot, and when Ritchot died in 1831, he drew up the inventory of his assets as a mark of gratitude and friendship. On 10 Jan. 1832, in Montreal, he married Henriette Cadieux, eldest daughter of the late Jean-Marie Cadieux, a notary. He then went to live on Rue Saint-Jacques, in a house his wife had inherited at her father’s death, and he also moved his office there. The couple were to have five children, but two of their daughters and their only son died in infancy. Through intelligence, transparent integrity, and devotion to work, Lorimier built up a good practice. His minute-book discloses that his clients in the main were members of the liberal professions, small merchants, craftsmen, and Canadian farmers from the town and island of Montreal; in particular he drew up a great many contracts for Gabriel Franchère*, the American Fur Company’s principal agent in Montreal, during the period from 1832 to 1837.

By his activity as a notary and his enthusiasm for politics Lorimier soon became an influential member of the professional middle class of Montreal and a figure close to the Patriote leaders. During the 1832 by-election to the assembly for Montreal West he was one of the keenest supporters of Daniel Tracey*, the publisher of the Montreal Vindicator and Canadian Advertiser, who had been imprisoned for libelling the Legislative Council, and he was largely instrumental in securing him the seat. However, on 21 May during a riot at the end of the polling in which three Canadians died, Lorimier narrowly escaped injury when a shot fired by a soldier of the 15th Foot broke the handle of his umbrella. He took an energetic part in the Patriote party’s campaign in the 1834 general election, supporting the candidates who were in favour of the 92 Resolutions. Two years later he eagerly contributed to the subscription launched by Édouard-Raymond Fabre* to compensate the publisher of La Minerve, Ludger Duvernay*, for his imprisonment on a charge of contempt of court.

Like most of Papineau’s supporters, Lorimier was strongly opposed to the British parliament’s adoption in March 1837 of Lord John Russell’s resolutions, which flatly rejected the Patriote party’s demands for reforms and confirmed the hold of the provincial executive on the public moneys of Lower Canada. Thus he threw himself into the resistance movement organized by the Patriote leaders in April. He was present at nearly all the large protest meetings in the Montreal region in the period preceding the rebellion. On 15 May he was appointed secretary for the Montreal County meeting held at Saint-Laurent on the island of Montreal. At this gathering a body to focus resistance, the Comité Central et Permanent du District de Montréal, was set up and Lorimier and George-Étienne Cartier* were elected co-secretaries. The committee was to meet weekly in Fabre’s bookshop on Rue Saint-Vincent, and its task would be “to attend to the political interests of this county” and “to correspond with the other counties” in order to coordinate resistance. On 29 June Lorimier also acted as secretary for the city of Montreal meeting that solemnly protested against the implementation of the Russell resolutions, “which annihilate the constitutional rights in the Province.” He made a point of honour of attending, along with many prominent Montreal Patriotes, the Assemblée des Six Comtés held on 23 October in Saint-Charles-sur-Richelieu. He went as well to the meeting of the Fils de la Liberté in Montreal on 6 November, only to be shot in the thigh during a clash between this society and the Doric Club which deteriorated into a ransacking of the Vindicator’s offices.

On 14 or 15 Nov. 1837, before warrants for the arrest of the Patriote leaders were issued by the governor, Lord Gosford [Acheson], Lorimier fled Montreal hurriedly, leaving behind his wife, children, possessions, and practice, and headed for the county of Deux-Montagnes. Arriving there on 15 November, he was soon appointed captain in the local militia battalion and was ordered to put himself under the command of Jean-Olivier Chénier at Saint-Eustache. During the month that followed he played an important role alongside Chénier and Amury Girod in preparing for armed struggle in the region. He was at the battle of Saint-Eustache on 14 December. Realizing the futility of the efforts to repel Sir John Colborne*’s forces, which were superior in number, he advised Chénier and his followers to lay down their arms, but in vain. At the height of the fighting he escaped, while there was still time, to the neighbouring village of Saint-Benoît (Mirabel). From there he went to Trois-Rivières with a few companions, crossed the St Lawrence, and finally reached the United States by way of the Eastern Townships.

After his arrival Lorimier stayed in Montpelier, Vt, for a time and then moved on to Middlebury, where a group of Patriotes had arranged to meet in order to discuss the possibility of a new uprising. Among those present on 2 Jan. 1838 were Lorimier, Papineau, Robert Nelson*, Edmund Bailey O’Callaghan*, Cyrille-Hector-Octave Côté, Édouard-Élisée Malhiot*, Édouard-Étienne Rodier, the curé Étienne Chartier*, and Lucien Gagnon. Undoubtedly Papineau’s temporizing and hesitant approach at this meeting disappointed Lorimier. A week later he was present at a meeting in Swanton. It was probably then that he came around to the views held by Nelson and Côté and to their plans for setting in motion an invasion of Lower Canada. After Nelson took command of the Patriote army and began preparing for the invasion, Lorimier went to join him at Plattsburgh, N.Y. On 28 February he was serving as a captain in the army that crossed the border. When Nelson read the proclamation of the independence of Lower Canada, Lorimier was at his side. Poor organization and planning and intelligence leaks doomed the expedition. Lorimier sought refuge in the United States, where he was imprisoned, along with others, for violating American neutrality. He was quickly acquitted by a jury sympathetic to the Patriote cause.

In the first months of exile Lorimier had a difficult time. To all intents and purposes he had given up his profession and consequently had no work or income. He was also without news of his family and worried about having left them in Montreal without means of subsistence. But rather than let himself be discouraged by his personal problems and by the set-back in February 1838, he decided to devote himself to reorganizing the rebel movement. By March Lorimier in all probability was helping to set up the Association des Frères-Chasseurs, which he undoubtedly lost no time joining. As Nelson and his colleagues saw it, the purpose of this secret, paramilitary society was to support the Patriote army by initiating an uprising inside Lower Canada once an offensive had been launched from the American border. In May Lorimier’s wife, Henriette, came to join him in Plattsburgh, where she lived with him until August. It can be assumed that her visit caused Lorimier to vacillate painfully between his obligations to his family and his commitment to revolution. He nevertheless returned to Lower Canada several times that summer to recruit members for the society and make preparations for the uprising in the counties of Deux-Montagnes and Beauharnois. On the strength of promises from Nelson and Côté, he assured those joining the society that an army enjoying the blessing of the American government would come to their support and provide the weapons and ammunition they needed. In July, having returned to Plattsburgh from one of these trips, he confided in a letter to a friend the deep feelings stirring in him just months before the new insurrection: “I am ever ready to spill my blood on the soil which gave me birth, in order to upset the infamous British Government – top, branches, roots, and all.”

It is difficult to determine exactly what role Lorimier played when the second uprising began on the night of 3–4 Nov. 1838. Laurent-Olivier David* says only that Lorimier was at Beauharnois when the Patriotes there seized Edward Ellice*’s seigneurial manor-house and went on board the steamship Henry Brougham to inspect it. The author of the account of Lorimier published in the Swanton North American on 15 May 1839 and another biographer, Hector Fabre*, state that Lorimier had the rank of brigadier general in the Patriote army at the time these events took place. François-Xavier Prieur, a merchant at Saint-Timothée who was one of the leaders of the uprising at Beauharnois, noted that until that night “de Lorimier had taken no active part in the movement, at least as far as I know.” What is certain is that once the Patriotes from Beauharnois had completed their mission, they waited in vain for Nelson’s orders.

On 7 November Lorimier and Prieur set out from Beauharnois with 200 men to reinforce the Patriotes at Camp Baker, in Sainte-Martine, who were facing the approach of an infantry regiment. Another leader of the uprising, Jean-Baptiste-Henri Brien, a doctor at Sainte-Martine, disclosed in a declaration made to the authorities two days after he was imprisoned on 18 November that Lorimier had come “to encourage the people to remain firm” and not to give up the fight. On 9 November after the Patriotes at Camp Baker had beaten off an attack by a detachment of the 71st Foot, Lorimier strongly condemned their commanding officer James Perrigo, a merchant at Sainte-Martine, for dissuading his companions from pursuing the soldiers as they fled. A few hours after the fighting ended the Patriotes from Beauharnois received news of Nelson’s defeat at Odelltown. They dispersed the next day, before two militia battalions from Upper Canada arrived. Those of them who were the most gravely compromised attempted under Lorimier’s leadership to seek refuge in the United States, but Lorimier himself, caught in the crossfire of a corps of volunteers, lost his way in the dark and was arrested near the border on the morning of 12 November. He was taken on foot to the jail in Napierville, and on 22 or 23 November was removed to Montreal Prison.

On 11 Jan. 1839 Lorimier, along with 11 companions, appeared before a court martial presided over by Major-General John Clitherow*. Shortly after the court opened, Perrigo was excluded from the trial. The accused were represented by lawyers Lewis Thomas Drummond* and Aaron Philip Hart, who were allowed to prepare only written pleas for their clients. Having consulted with them, Lorimier made an initial protest challenging the jurisdiction of the court martial and demanded a trial before a civil court. His demand was dismissed. The trial was conducted in an atmosphere of violence. Lorimier defended himself tenaciously in a hall filled with officials eager for blood. He proceeded to cross-examine the witnesses, led them to contradict themselves, and disputed all the evidence brought against him. It was so much wasted effort. Unbeknown to Lorimier, Brien, who was terrified at the prospect of mounting the scaffold, had already signed a declaration informing in particular against his companion in return for the authorities’ promise that he would be treated leniently. This confession proved more damaging to Lorimier than any of the testimony given by witnesses. Having failed to capture the principal leaders of the rebellion, the authorities fell back on the one they considered the most prominent of the Beauharnois rebels. Charles Dewey Day*, the deputy judge advocate, specifically attacked Lorimier, depicting him in his address to the court as an extremely dangerous criminal who had fomented the rebellion and deserved to die on the gallows. At the end of the trial on 21 January, the accused were all found guilty of high treason; Lorimier alone was not recommended to the executive for clemency.

Drummond and Hart took repeated steps with Governor Colborne and the members of the Special Council to save Lorimier’s life, but in vain. On 9 Feb. 1839 they made their final move, asking for a writ of prohibition. Unfortunately, the Court of King’s Bench rejected the request. On 14 February Henriette de Lorimier sent a letter to Colborne begging him to reprieve her husband, whose execution had been decreed the day before. Colborne did not even deign to reply to her petition.

On 15 Feb. 1839, at 9:00 a.m., Lorimier mounted the steps of the scaffold with a firm tread, in company with Charles Hindenlang, Amable Daunais, François Nicolas, and Pierre-Rémi Narbonne. On the eve of his execution he had written his political testament, in which he expressed the hope that his country would one day be liberated from British domination. He concluded it with moving and pathetic words: “As for you, my compatriots – may my execution and that of my companions on the scaffold be of use to you. May they show you what you must expect from the British government. I have only a few hours to live, but I wanted to divide this precious time between my religious duties and the duty [I owe] to my countrymen. For them do I die on the gibbet the infamous death of the murderer; for them do I part from my young children, [and] from my wife, who have only my industry for their support; and for them do I die exclaiming – ‘Long live Liberty! Long live Independence!’” Lorimier’s body was buried in the former Catholic cemetery of Montreal, where Dominion Square is today. His wife, unable to pay the debts that he had contracted, was obliged to renounce his estate. Lorimier’s remains are believed to have been exhumed in 1858 and in all probability were placed beneath the memorial in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery dedicated to the victims of 1837–38.

In 1883 journalist Laurent-Olivier David got up a public subscription to assist Henriette de Lorimier and her two daughters, who were living in poverty at L’Assomption. With the help of Honoré Beaugrand*, publisher of La Patrie, and writer Louis-Honoré Fréchette*, he collected $1,300; $1,000 went to Lorimier’s widow by way of reparations from the nation. That year the Montreal city council in a fitting reversal passed a resolution changing the name of Avenue Colborne to Avenue de Lorimier. According to the North American, Lorimier was of roughly medium height and had a dark complexion and black hair and eyes. In an article on him in the 10 March 1881 issue of L’Opinion publique, David described him as having an “oval-shaped” face, regular features, a high forehead, and a “gentle and intelligent countenance.” “One thought on sight,” David concluded, “of a good-hearted, imaginative man with a refined intellect.”

That a figure such as Chevalier de Lorimier has been presented in very different ways in historical works is hardly surprising. There is one point, however, on which historians and his biographers are in agreement: the sincerity of his convictions. Historian Pascal Potvin, though he condemned the blindness of some of the leaders in the 1838 rebellion, was forced to recognize this quality in Lorimier. The author of the North American biography and David maintained that Lorimier was one of the Patriotes who believed most strongly that the rebellion would succeed. True to himself, he had carried out the mission that had been entrusted to him: the Beauharnois Patriotes had fulfilled their part in the planned invasion, and they had then formed one of the last groups of insurgents to resist the British army. Lorimier’s only errors were probably to have trusted too much in Nelson and Côté for the preparation and progress of the uprising – but could he have done otherwise under the circumstances? – and to have believed in the Americans’ promise of support. His greatest merit was to have taken to the limit his political ideal and his revolutionary commitment, at the cost of his own life. Lorimier has won his place in history as a great Patriote and as a martyr to the cause of independence for Lower Canada.

Chevalier de Lorimier’s minute-book, containing notarized instruments for the years 1829–38, is at ANQ-M, CN1-122. Originals and copies of some interesting correspondence with his wife, relatives, and friends, which he wrote mostly during the time he spent in the Montreal jail, are located in various archives, including the following: ANQ-M, P-224/1, no.78; ANQ-Q, E17/37, no.2972; P1000-8-124; P1000-49-976; P1000-66-1317; P1000-87-1806; ASQ, Fonds Viger–Verreau, carton 67, no.6; ASTR, 0032 (coll. Montarville Boucher de la Bruère), papiers Wolfred Nelson; BVM-G, mss, Lorimier à [L.-A.] Robitaille, 12 févr. 1839; and David MacDonald Stewart Museum (Montreal), Lady La Fontaine album, Lorimier à [Lady La Fontaine (Adèle Berthelot)], 15 févr. 1839. The declaration of political principles which Lorimier wrote on the eve of his execution is at ANQ-Q, E 17/37, no.2971 (copies in P1000-49-976 and P1000-66-1317).

Lorimier’s correspondence has been reproduced in newspapers and other publications. The North American, a paper put out by sympathizers to the Patriote cause, published most of his letters on 15 May, 7 Aug., 6 Nov. 1839 and 22 Jan., 24 June, 25 July 1840 (the issue of 22 Jan. 1840 contains a letter which is particularly illuminating about his state of mind while he was planning the second insurrection of July 1838). In addition, Ludger Duvernay’s Le Patriote canadien (Burlington, Vt.), a paper for Patriotes who had sought refuge in the United States, printed a few items in its issue of 13 Nov. 1839. Less than ten years later, author James Huston* included all of Lorimier’s letters in Le répertoire national (1848–50), 2: 97–108. Toward the end of the 19th century Laurent-Olivier David also published the entire correspondence in “Les hommes de 37–38: de Lorimier,” L’Opinion publique, 10 févr. 1881: 61–62; 3 mars 1881: 97; 10 mars 1881: 109–10; this article was reprinted in his Patriotes, 237–63. Some correspondence has been published in the 20th century: “Testament politique de Chevalier de Lorimier (14 février 1839)” and “Lettre du patriote Chevalier de Lorimier à sa femme (15 février 1839),” ANQ Rapport, 1924–25: 1, 32; “Lettre de Chevalier de Lorimier à Pierre Beaudry (14 février 1839),” ANQ Rapport, 1926–27: 145; and “Lettre du Chevalier de Lorimier au baron de Fratelin (15 février 1839),” BRH, 47 (1941): 20.

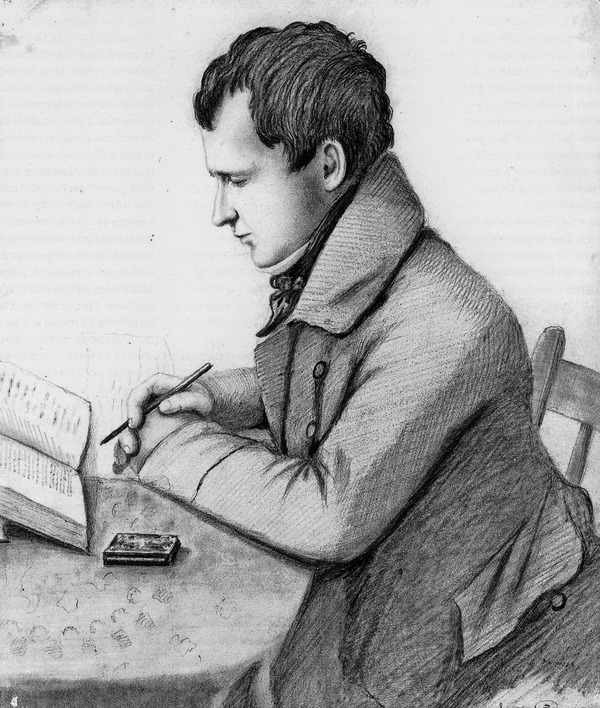

A pencil sketch of Lorimier, attributed to Jean-Joseph Girouard*, is found in the Lady La Fontaine album, David MacDonald Stewart Museum.

ANQ-M, CC1, 23 avril 1839; CE1-51, 10 janv. 1832; CE5-19, 27 déc. 1803; CN1-32, 10–13 mai, 20 juin 1839; CN1-270, 3 sept. 1823, 9 janv. 1832. ANQ-Q, E17/6, no.7; E17/14, no.793; E17/27, nos.2027–30; E17/28, nos.2031, 2047, 2051, 2058–60, 2062–63, 2075; E17/37, nos.2968, 2973; E17/39, no.3116; P-68/3, no.313; P-68/4, no.429; P-68/5, no.559; P-92. Arch. de la ville de Montréal, Doc. administratifs, procès-verbaux du conseil municipal, 27 juin 1883. BVM-G, Fonds Ægidius Fauteux, notes compilées par Ægidius Fauteux sur les patriotes de 1837–38 dont les noms commencent par la lettre L, carton 6. David MacDonald Stewart Museum, Pétition, janvier 1828. PAC, MG 24, A2, 50; A27, 34; B2, 17–21; B39; RG 4, B8: 2908–18; B20, 28: 11218–19, 11256–59, 11297–300; RG 31, C1, 1825, 1831, Montreal. [Henriette Cadieux], “Lettre de la veuve du patriote de Lorimier au baron Fratelin,” BRH, 46 (1940): 372–73. “Un document inédit sur les événements assez obscurs de l’insurrection de 1837–38,” [F.-L.-G.] Baby, édit., Canadian Antiquarian and Numismatic Journal, 3rd ser., 5 (1908): 3–31. Amury Girod, “Journal kept by the late Amury Girod, translated from the German and the Italian,” PAC Report, 1923: 370–80. “Papiers Duvernay,” Canadian Antiquarian and Numismatic Journal, 3rd ser., 6: 6–7, 9–10; 7: 20–23, 25–26, 184–85. L.-J.-A. Papineau, Journal d’un Fils de la liberté. F.-X. Prieur, Notes d’un condamné politique de 1838 (Montréal, 1884; réimpr. 1974), 89–139. Rapport du comité choisi sur le gouvernement civil du Canada (Québec, 1829), 351–53. Report of state trials, 1: 293–376; 2: 141–286, 548–61. Le Canadien, 15 nov. 1839. La Minerve, 13, 20 déc. 1827; 10, 28 janv. 1828; 21 sept. 1829; 11, 15, 18 mai, 29 juin 1837. Montreal Gazette, 22 Jan., 19 Oct. 1839. North American, 22 May, 4, 11, 18 Dec. 1839.

Appleton’s cyclopædia of American biography, ed. J. G. Wilson and John Fiske (7v., New York, 1888–1901), 4: 26–27. Fauteux, Patriotes, 19–20, 65–74, 141–42. J.-J. Lefebvre, Le Canada, l’Amérique: géographie, histoire (éd. rév., Montréal, 1968), 175. Le Jeune, Dictionnaire, 2: 168–69. Montreal directory, 1819. Quebec almanac, 1830–38. Wallace, Macmillan dict. J. D. Borthwick, History of the Montreal prison from A.D. 1784 to A.D. 1886 . . . (Montreal, 1886), 40, 43–44, 51–52, 90–96. L.-N. Carrier, Les événements de 1837–38 (2e éd., Beauceville, Qué., 1914). Chapais, Cours d’hist. du Canada, 3: 189–91. Christie, Hist. of L.C. (1866). David, Patriotes, 171–72, 277–86. Émile Dubois, Le feu de la Rivière-du-Chêne; étude historique sur le mouvement insurrectionnel de 1837 au nord de Montréal (Saint-Jérôme, Qué., 1937), 122, 177–78. Hector Fabre, Esquisse biographique sur Chevalier de Lorimier (Montréal, 1856). Émile Falardeau, Prieur, l’idéaliste (Montréal, 1944). Filteau, Hist. des patriotes (1975), 117, 207–8, 274–76, 301–6, 358–63, 371, 401–22, 435–39. [C.-A.-M. Globensky], La rébellion de 1837 à Saint-Eustache avec un exposé préliminaire de la situation politique du Bas-Canada depuis la cession (Québec, 1883; réimpr. Montréal, 1974). Augustin Leduc, Beauharnois, paroisse Saint-Clément, 1819–1919; histoire religieuse, histoire civile; fêtes du centenaire (Ottawa, 1920), 175–78. Michel de Lorimier, “Chevalier de Lorimier, notaire et patriote montréalais de 1837–1838” (thèse de ma, univ. du Québec, Montréal, 1975). É.-Z. Massicotte, Faits curieux de l’histoire de Montréal (2e éd., Montréal, 1924), 86–98. Maurault, Le collège de Montréal (Dansereau; 1967). Ouellet, Bas-Canada. J.-E. Roy, Hist. du notariat, 2: 453; 3: 7, 9–17. P.-G. Roy, Toutes petites choses du Régime anglais (2 sér., Québec, 1946), 2: 33–36. Rumilly, Papineau et son temps. Robert Sellar, The history of the county of Huntingdon and of the seigniories of Chateauguay and Beauharnois from their first settlement to the year 1838 (Huntingdon, Que., 1888), 505–43. André Vachon, Histoire du notariat canadien, 1621–1960 (Québec, 1962). Mason Wade, Les Canadiens français, de 1760 à nos jours, Adrien Venne et Francis Dufau-Labeyrie, trad. (2e éd., 2v., Ottawa, 1966), 1: 342.

Ivanhoë Caron, “Une société secrète dans le Bas-Canada en 1838: l’Association des Frères Chasseurs,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 20 (1926), sect.i: 17–34. L.-O. David, “Les hommes de 37–38: de Lorimier,” L’Opinion publique; 24 mars 1881: 133–34; 7 avril 1881: 157–58; 14 avril 1881: 169–70; 21 avril 1881: 181. “De Lorimier,” L’Opinion publique, 28 juin 1883: 301. L.-A. Fortier, “Correspondance: victimes de 37–38,” La Tribune (Montréal), 24 mars 1883: 2. J.-J. Lefebvre, “Jean-Marie Cadieux, notaire, 1805, et sa descendance,” La Rev. du notariat (Outremont, Qué.), 69 (1966–67): 122–32, 196–202. É.-Z. Massicotte, “La famille de Lorimier: notes généalogiques et historiques,” BRH, 21 (1915): 10–16, 33–45. Victor Morin, “Clubs et sociétés notoires d’autrefois,” Cahiers des Dix, 15 (1950): 185–218; “La ‘République canadienne’ de 1838,” RHAF, 2 (1948–49): 483–512. Pascal Potvin, “Les patriotes de 1837–1838: essai de synthèse historique,” Le Canada français (Québec), 2e sér., 25 (1937–38): 667–90, 779–93. Marcelle Reeves-Morache, “La Canadienne pendant les troubles de 1837–1838,” RHAF, 5 (1951–52): 99–117. “La veuve de Lorimier,” L’Opinion publique, 19 juill. 1883: 340. “La veuve du patriote de Lorimier,” BRH, 32 (1926): 330.

Cite This Article

Michel de Lorimier, “LORIMIER, CHEVALIER DE (baptized François-Marie-Thomas) (François-Marie-Thomas-Chevalier de Lorimier),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lorimier_chevalier_de_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lorimier_chevalier_de_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michel de Lorimier |

| Title of Article: | LORIMIER, CHEVALIER DE (baptized François-Marie-Thomas) (François-Marie-Thomas-Chevalier de Lorimier) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |