Source: Link

MASSEY, LILLIAN FRANCES (Treble), philanthropist and educator; b. 2 March 1854 in Newcastle, Upper Canada, only daughter of Hart Almerrin Massey* and Eliza Ann Phelps; m. 26 Jan. 1897 John Mill Treble in Toronto; they had no children; d. 3 Nov. 1915 in Santa Barbara, Calif., and was buried in Toronto.

Educated in Newcastle and at Wesleyan Female College in Hamilton, Lillian Massey moved with her parents to Cleveland, Ohio, in 1871. There she attended the Cleveland Female Seminary and by 1876 was involved in the Sunday school and the missionary and women’s aid societies of First Methodist Episcopal Church. She participated, as well, in family outings to the religious-educational Chautauqua Assembly at Chautauqua Lake, N.Y. In 1882 the Masseys settled in Toronto, where Hart soon resumed control of the family’s implement-manufacturing business. Though frail, Lillie travelled widely, taking world trips in 1877–78 and 1887–88. She was ever subject to the custodial attentions of her father and brothers. Only by the mid 1890s did she, in her forties, begin to emerge from domestic anonymity.

Hart Massey’s wealth and charitable interests gave his demure daughter the opportunity to make the “difficult art” of philanthropy her calling. That she would devote herself to helping women was evident from her early work in women’s aid, her reading of redemptive literature, and her special interest (piqued at Chautauqua and elsewhere) in the emerging field of household science. These preoccupations found encouragement in the pioneering efforts at social reform by Methodists in Toronto. Lillian subscribed from 1888 to the inner-city work of Metropolitan Church, supported the Toronto City Missionary Society, and in 1894 helped her father establish the Fred Victor Mission for “direct evangelistic ministry” to the poor and profligate. At his death in 1896, Lillian and her surviving brothers, Chester Daniel and Walter Edward Hart*, not only received substantial inheritances but were named trustees of his estate and thereby made responsible for the philanthropic disposition of more than $1 million. Until 1899, for instance, the Masseys continued to fund the operation and expansion of the Deaconess Home and Training School in Toronto.

In 1896, “convinced that social reform must take account of household conditions,” Lillian started at the Victor mission a “kitchen garden” and sewing and cooking classes for young women and girls from the surrounding slums. Lillian was in a privileged position: few Canadian women had the means to realize such a concept within a predominantly male institution. Though she was involved in planning and equipping the classes, instruction and in-home demonstrations were initially provided by staunchly middle-class deaconesses, a number graduates of the Chicago Methodist Episcopal Training School and the Drexel Institute of Technology in Philadelphia.

The classes at the mission did not have the impact likely desired by Lillian. After visiting domestic science schools abroad, in 1900 she set up the separate Lillian Massey School of Household Science and Art. Almost immediately she moved to broaden the base of support for household science. Later in the same year she approached Ontario’s Department of Education to start a program for training teachers in conjunction with her school. The idea was accepted the following year, the school was renamed the Lillian Massey Normal Training School of Household Science, and enrolment began in February 1902. Moreover, she worked to have household science established at the university level. A member of the Toronto branch of the National Council of Women of Canada, she enlisted the help of the Winnipeg branch to have a program implemented at the University of Manitoba in 1902. The next year she agreed to fund one at Mount Allison College in Sackville, N.B., if it was made a permanent department, a condition accepted in early 1904. She also supported a department at Columbian Methodist College in New Westminster, B.C.

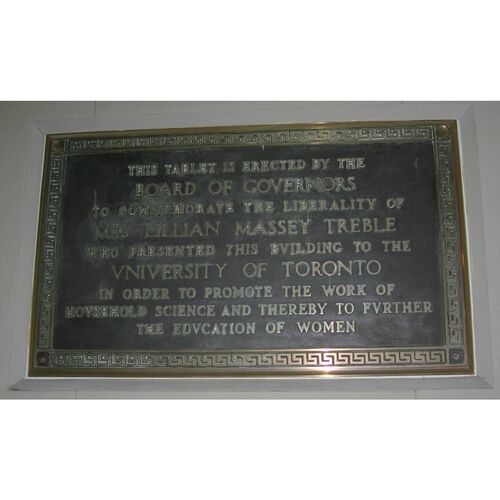

Her greatest progress was achieved at the University of Toronto. Working through Nathanael Burwash, a family friend, she succeeded in having the country’s first four-year degree program in household science instituted in 1902. Normal training at the Massey school was transferred to it in 1905. A year later a faculty was set up under the direction of the school’s former principal, Annie Lewisa Laird*, and Massey agreed to provide a building. Begun in 1908 and opened in 1913, it was regarded as the finest facility on the continent and went far to counter persistent questioning of the credibility of household science. The structure was designed by family architect George Martell Miller, but Massey and Laird planned much of the interior. In addition, Lillian set up a household science school at the Azabu Methodist mission in Tokyo, and was probably influential in Chester’s decision to fund a “diet kitchen” at Toronto General Hospital.

Lillian Massey’s views on social reform through domestic science emerge in part from the work she sponsored; her own thoughts remain elusive. The females who attended the classes at the Victor mission were evidently “self-respecting poor.” Some success was claimed among them but reports by the deaconesses displayed contempt for many working-class and immigrant mothers, whom they regarded as poor nurturers and thus a cause of domestic problems. Further, Massey’s student teachers, by showing mothers and daughters how to prepare only cereals, beans, and tough meats, were perhaps realists but none the less sustained class distinctions. Biases were also apparent in the travellers’ aid work initiated by Massey through the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in 1903 and performed by deaconesses looking for fallen women.

Massey’s initiatives in domestic science were not undertaken in a vacuum. At least one other school operated in Toronto in the 1890s. Adelaide Sophia Hoodless [Hunter*] of Hamilton championed the movement, to great effect, though she never enjoyed the financial independence or denominational backing that shielded Massey, who rarely operated in public. Massey and Hoodless did not have a cordial relationship, but they both promoted a conservative version of the home economics movement, wherein women’s destiny lay in the home. This position contrasted sharply with that of Alice Amelia Chown*, whom Massey knew through the Canadian Household Economic Association of which she was honorary president in the 1900s. Not only would Chown use the movement to challenge the traditional role of women, but she also came to advocate a secular and scientific approach to social work that threatened the volunteer philanthropy exemplified by Massey.

Lillian drew unquestioning support from her family, particularly Chester, her sole surviving brother after 1901. In 1897, at age 43, she had married John M. Treble, a men’s-wear dealer with children. A director or treasurer of such Methodist organizations in Toronto as the Victor mission, he knew the Masseys well. After their marriage Lillian and John resided at her mother’s home, Euclid Hall, which Lillian remodelled, displaying the same flair for design as had her father. She put together a collection of Chinese robes and Mediterranean embroideries, which she donated to the Royal Ontario Museum “to give the women of Canada a standard of what is possible in the arts of weaving and embroidery.”

Lillian’s constitution was invariably described as delicate. Raymond Hart Massey*, with some exaggeration, would remember his aunt as a “confirmed hypochondriac and dietary faddist.” Beginning in the 1900s she suffered long periods of undiagnosed ill health, made worse by her husband’s death in 1909 and the “heavy burden” of establishing the household science faculty in Toronto. Recuperative trips to Atlantic City, N.J., New Hampshire, Arizona, and, finally, California were marked by pathetic letters to Chester, fretting over her cherished household science building and asking him to visit. Lonely and “badly crippled by neuritis,” she died in 1915, leaving an estate worth more than $2 million, which included bequests of $100,000 for the maintenance of the household science faculty and $300,000 for training Methodist clergy.

In praising her, male Methodist eulogists evoked without intended contradiction Lillian’s autonomous achievements and her conformity to a conventional model. “In her retirement into the narrower sphere of home life she embodied the finest characteristics of Christian womanhood. Patient in suffering, her quiet, invalid life was passed uncomplainingly and in submission to the divine will.”

AO, RG 2-29, box 3, domestic science files, 1882–1905; RG 2-103; RG 22-305, nos.22009, 30966. NA, MG 32, A1. UCC-C, Church records, Toronto Conference, Fred Victor Methodist/United Mission records. UTA, A73-0026/312(03); A75-0008; A85-0020. Christian Guardian (Toronto), 10, 17 Nov., 29 Dec. 1915. Allisonia (Sackville, N.B.), 1 (1903–4)–11 (1913–14). Mollie Gillen, The Masseys: founding family (Toronto, 1965). In memory of Lillian Massey Treble ([Toronto, 1915?]; copy at UCC-C). R. [H.] Massey, When I was young (Toronto, 1976). Alison Prentice et al., Canadian women: a history (Toronto, 1988). E. C. Rowles, Home economics in Canada; the early history of six college programs: prologue to change (Saskatoon, [1964]). Patricia Saidak, “The inception of the home economics movement in English Canada, 1890–1910: in defence of the cultural importance of the home”

Cite This Article

David Roberts, “MASSEY, LILLIAN FRANCES (Treble),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 20, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/massey_lillian_frances_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/massey_lillian_frances_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Roberts |

| Title of Article: | MASSEY, LILLIAN FRANCES (Treble) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | February 20, 2026 |