Source: Link

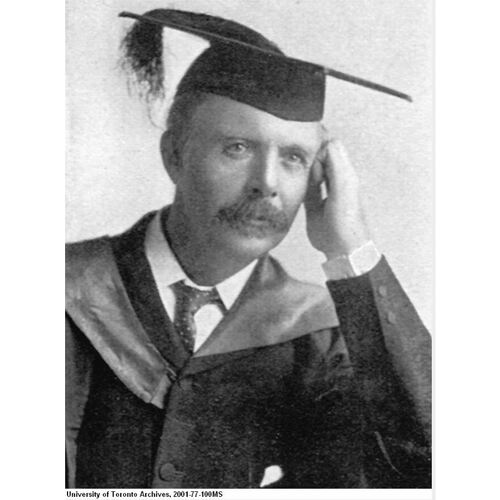

HUTTON, MAURICE, scholar and educator; b. 8 Oct. 1856 in Manchester, England, son of the Reverend Joseph Henry Hutton and Mary Mottram; m. 2 July 1885 Annie Margaret McCaul (1849–1923) in Toronto; d. there 5 April 1940.

Maurice Hutton’s father, a graduate of the University of London, was a Unitarian minister who later embraced the Church of England. One of Maurice’s uncles was Richard Holt Hutton, owner and joint editor from 1861 of the Spectator (London) and a leading 19th-century British intellectual. After attending Magdalen College School in Oxford, Maurice entered the university there. He graduated with a first in literae humaniores from Worcester College in 1879 (ma 1882), won a fellowship at Merton College, and then taught for a year at what would become the University of Sheffield.

In 1880 Hutton was made professor and chair of classics at University College, Toronto, which had been established in 1853 by the University of Toronto Act. Classics was considered to be the most important chair in the university, and the previous incumbent, John McCaul*, had also been president of the college. Unable to find another person qualified to hold both positions, the Ontario government had named Daniel Wilson* president. The appointment of Hutton, a 23-year-old Englishman, to the classics chair, initially at a higher salary than that of the other professors, sparked something of a nativist backlash. But Hutton quickly won golden opinions for his scholarship, teaching, and personality, and for staging, in 1882, the third production in the English-speaking world of Sophocles’s Antigone in the original Greek, in which he played the title role. The production attracted wide attention. It involved students and staff as actors, members of the chorus, and musicians, and it was long remembered by many students as the high point of their university experience. Three years later Hutton married Annie McCaul, his predecessor’s daughter. They would have three children: Guy Maurice, who attended the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston and joined the Indian cavalry; Ruth Marjorie, a brilliant scholar whose premature death from pneumonia in 1929 was a devastating blow; and Mary Joyce, who in 1922 married future diplomat Humphrey Hume Wrong*, son of the historian George MacKinnon Wrong*, Hutton’s colleague.

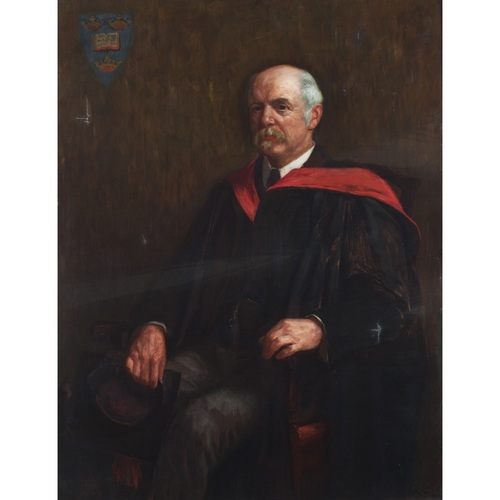

“An epoch in universities,” wrote Sir Robert Alexander Falconer* in 1929, “is often characterized by one or more persons who have lived and worked long enough to impress themselves upon the period. Of such persons, Toronto has known one in Maurice Hutton.” After holding the chair of classics at University College for seven years, Hutton served as professor of Greek (1887–1928) and the college’s principal (1901–28). Having stipulated that he had no interest in the permanent position of president of the university, he was made acting president for 1906–7, following the resignation of James Loudon*. During his period in office, the faculties of forestry under Dean Bernhard Eduard Fernow*, education under Dean William Pakenham*, and home economics [see Lillian Frances Massey*] were established, and the School of Practical Science, loosely affiliated with the university, was transformed into its faculty of engineering. He also worked with Father Henry Carr* to bring St Michael’s College into the university as a federated college, a process that would be completed in 1910. Such was Hutton’s adroit diplomacy and calm leadership that many hoped his appointment might be made substantive, but Hutton gracefully returned to University College and provided strong support to Loudon’s successor, President Falconer.

A self-effacing man with immense personal magnetism, Hutton inspired generations of students who became the leaders of a growing country (though his ability to translate Lewis Carroll into Greek verse, said his colleague David Reid Keys, added “new terrors to the examination papers”). His contributions to his community were recognized by honorary llds from Toronto (1902), Queen’s (1903), McGill (1918), and McMaster (1923). Elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1913, he served as president of its section ii in 1918–19. Outside academia, he belonged to such organizations as the Ontario Educational Association and the Toronto branch of the League of the Empire, and he won a wide public following with popular lectures and articles, a number of which were collected in Many minds ([1927]), All the rivers run into the sea ([1928]), and The sisters Jest and Earnest (1930). In 1930, shaken by his daughter’s death, he fell ill with pleural neuralgia, and for the last decade of his life he was an invalid.

As a professor, Hutton was instrumental in designing – with his associate William Dale* – the honours program in classics at the university. He replaced his father-in-law’s belletristic approach to classical literature with the Oxford emphasis on the historical and philosophical content of the great works of antiquity (Plato’s writings, he believed, “anticipated all the ideas dominant or dormant in our own civilization”). Students were encouraged to encounter a significant body of literature, reflect on its meaning, and develop critical judgement as well as learning and culture. This approach informed the teaching of the humanities in Toronto until the 1960s and was imitated throughout English Canada. Its focus was on education, not research: “Every one who thinks for himself is a researcher,” Hutton said, “though what he discovers for himself be as old as the hills and has been discovered before him by his ancestors in every generation.” Hutton’s translation of Tacitus’s Agricola and Germania for the Loeb Classical Library (1914) (published in one volume with William Peterson*’s translation of the Dialogus) was praised for its elegance but criticized for not reflecting the latest sources. His most important work, The Greek point of view (1925), got a poetical review in London’s Punch (“livelier by far / Than most contemporary novels are”) but a less favourable reception from North American scholars.

Hutton envisioned the ancient Greeks as a people who cultivated intellect to the exclusion of character and instinct, whose concepts of virtue, politics, and society were based entirely on enlightened self-interest. Their philosophers, artists, and scientists made unsurpassed achievements, but their cold logic could countenance killing strangers or euthanizing the unfit. They could never develop a political system beyond the city-state or conduct honest business. Restless and childlike – happy in youth and miserable in old age – they delighted in words, debate, art, and novelty. By contrast, the Romans, whose austere gravitas was grounded in intuition rather than reason, were fitted to conquer, build, organize, and govern, but were easily corrupted by the cleverer Greeks. According to Hutton, the sterility of the ancient world was redeemed by Christianity, which added to intellect and instinct the promise of salvation in return for striving – and a faith, hope, and charity rooted in an emotional commitment to the teachings and example of Christ. Christianity absorbed the best of classical culture and laid the foundation for a civilization that far surpassed that of the ancient world.

“Life,” Hutton wrote, “is a balance and a compromise not to be solved by fanatics.” Healthy people needed to combine opposites: intellect and instinct; masculine and feminine; liberal and conservative; Greek and Roman; Christianity and classical culture; science and humanism. Nations also needed balance. The British empire blended the Roman-like practicality of the English, the mental keenness and business sense of the Scot, and the poetry and intellect of the Irish with evangelical Christianity, industry, and science, and added to them the democracy, optimism, and energy of the dominions to become the greatest instrument for civilization the world had seen. But industrialism, modernism, and egalitarianism threatened to upset this balance and replace true democracy, which was rule by the best men, the best instincts, and the best attributes – what Hutton termed “quality” – with “equality,” by which he meant the rule of the city mob, swayed by the mood of the moment, setting no people, ideals, or characteristics higher than any others. The great mission of higher education in a democratic society was to develop leaders with intelligence and character, manners and morals, self-control, judgement, humanity, and humility – in the words of his disciple William Stafford Milner, to make “citizens of all … and sane and noble leaders of a few.” Classical education was best fitted to achieve this goal because it combined the discipline, even drudgery, required to master ancient languages with the development of a critical intellect that resulted from deep immersion in the great ideas on which western civilization is founded.

The First World War rendered Hutton increasingly pessimistic. Before the conflict he had advocated military training to offset the physical and moral degeneracy of industrial society by producing men of discipline and chivalry; after the war he became an ardent champion of the League of Nations. His beloved classical course had retained its primacy at Toronto longer than in most places, but it was now (as he had foreseen and lamented many years before) “the sister who sits faded and humble in shabby attire, struggling to revive the ancient embers of a dying fire, another Cinderella but without a fairy Prince.” The decline of religious idealism, and the egalitarianism, commercialism, and hedonism of the 1920s, increased his fear that the failure of the ancient world would be repeated unless a new basis for religious belief could be found that satisfied both the intellect and the emotions. He saw society as “living in an interregnum, waiting for a revival of a Christianity more passionate and more comprehensible, more scientific, more Platonic than we have found it; for the voice of a Master who shall again speak with authority and justify the way of God to men.”

Hutton’s scholarly exploration of the tension between the ancient and modern worlds was developed to its fullest extent by one of his students, Charles Norris Cochrane*, whose Christianity and classical culture (published the year Hutton died) treated the subject “with a completeness and balance,” in the words of fellow professor Arthur Sutherland Pigott Woodhouse, “for which Hutton never cared to labour.” Hutton’s vocation, as a scholar, teacher, and public intellectual, was to embody and express the best of the culture, thought, and values of both classical antiquity and Victorian Christianity, and to ensure that the young democracy of his adopted country would be led by people imbued with these ideals and values. His classical course and methods of teaching did much to shape higher education in the humanities in Canada for two generations. But his richest legacy was the thousands of students who came to believe, like educator Edmund Henry Oliver, that “the mission of Maurice Hutton in this world is not simply to instruct but also to inspire.”

Maurice Hutton’s major works mentioned in the text were all published initially in London. Among his numerous articles should be noted “Militarism and anti-militarism,” Univ. Magazine (Montreal), 12 (1913): 179–96, and his address to the Canadian Instit. on its semi-centennial, which appears in its Trans. (Toronto), 6 (1899): 651–54.

A. F. Bowker, “Truly useful men: Maurice Hutton, George Wrong, James Mavor and the University of Toronto, 1880–1927” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1975). C. N. Cochrane, Christianity and classical culture: a study of thought and action from Augustus to Augustine (Oxford, Eng., 1940). R. A. Falconer, “Maurice Hutton (1856–1940),” RSC, Trans., 3rd ser., 34 (1940), proc.: 111–14. A group of classical graduates, Honour classics in the University of Toronto, foreword R. [A.] Falconer ([Toronto], 1929). D. R. Keys, “Principal Maurice Hutton,” Univ. of Toronto Monthly, 28 (1927–28): 415–17. E. H. Oliver, “Principal Hutton,” Varsity (Toronto), 29 Oct. 1901: 25–26. S. E. D. Shortt, The search for an ideal: six Canadian intellectuals and their convictions in an age of transition, 1890–1930 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1976), 77–93. M. W. Wallace, “Principal Maurice Hutton,” Univ. of Toronto Monthly, 40 (1939–40): suppl. following p.172. A. S. P. Woodhouse, “Staff, 1890–1953,” in University College: a portrait, 1853–1953, ed. C. T. Bissell (Toronto, 1953), 51–83.

Cite This Article

Alan F. Bowker, “HUTTON, MAURICE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 9, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hutton_maurice_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hutton_maurice_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Alan F. Bowker |

| Title of Article: | HUTTON, MAURICE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | March 9, 2026 |