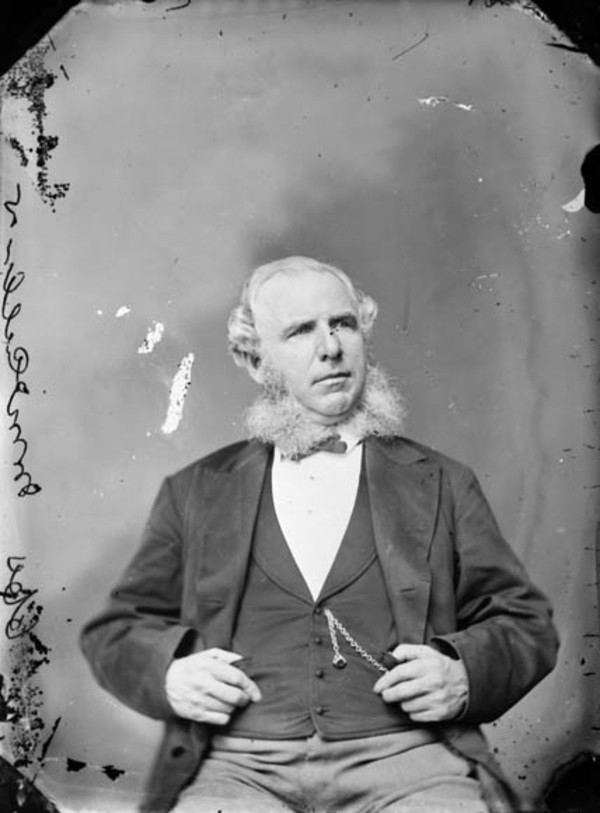

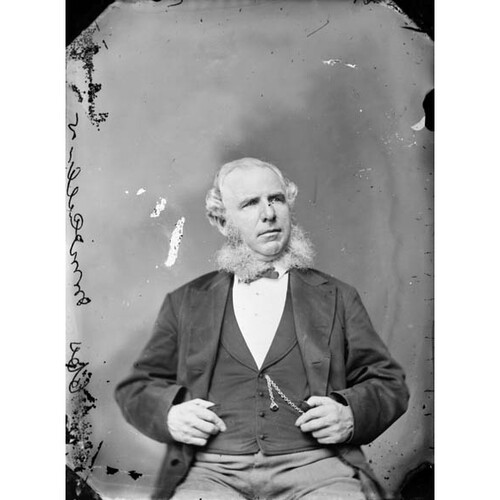

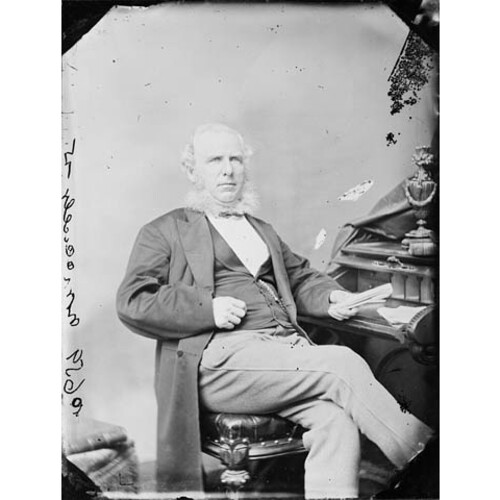

McCULLY, JONATHAN, lawyer, journalist, senator, and judge; b. on a farm in Cumberland County, N.S. (probably at Maccan), 25 July 1809, fifth in a family of nine children of Samuel McCully and Esther Pipes; d. at his home in Halifax, N.S., 2 Jan. 1877.

Jonathan McCully attended the usual one-room school until he had exhausted what it offered, then began work on his father’s 150-acre farm. From 1828 to 1830 he taught school to earn money to study law, which at that time meant a five-year apprenticeship to a lawyer. He was admitted to the bar in 1837 at the age of 28. McCully enjoyed fighting his cases and put much hard work on them. He was not without elements for success in a colonial society: ambition, thoroughness, and, perhaps one can add, poverty. Yet he was one of those who succeed by grit rather than by brains. He was always a slow, rather unoriginal thinker. Nor was he a great orator. He spoke with force and directness, often with homely allusions laced occasionally with slang, but neither in force nor in metaphor, nor in his public presence, was he the equal of Joseph Howe, whom McCully seems much to have admired.

By 1837 McCully was a convinced Reformer, despite Cumberland County’s Tory preponderance, and had begun to write political articles in the Halifax Acadian Recorder in much the same terms as he conducted his law practice. He was a vigorous, slashing writer, who spared nothing and no one. Under the pseudonym, “Clim o’ the Cleugh,” he made some savage comments in the Recorder on Alexander Stewart* in 1839. His support of Howe in the 1847 election was repaid with his appointment in 1848 to the Legislative Council, a position he continued to hold until 1867. McCully was appointed judge of probate in 1853, an office he held until after the change of government in 1857, when he was duly fired. He then opened a law practice with Hiram Blanchard, mla, Inverness, a partnership which lasted until McCully left the bar for the bench.

In 1842 McCully married Eliza Creed of Halifax; they had three children, a son and two daughters. The son, Clarence, was ultimately to go into the Anglican Church, but it was a berth rather than a vocation; he was a continued disappointment to his father.

While in the probate court McCully had supported Howe’s railway projects, one of which was to build, as a government work, a line from Halifax to Truro with a branch to Windsor. His reward was membership on Howe’s railway commission from 1854 until Howe’s government was replaced by the James W. Johnston-Charles Tupper* government in 1857. It is remarkable that McCully acquired so many offices; in 1855, for example, he was a member of the Legislative Council, a judge of probate, and a railway commissioner.

He was by now beginning to write for the Halifax Morning Chronicle, the Liberal party’s lighthouse in the capital. He rapidly became its leading editorial writer, a position he was to retain until 1865. McCully had the pleasure of seeing some of his efforts on behalf of William Young*, Howe, and the Liberals bear fruit, for in 1860 the Liberals (the name “Reformers” was falling out of use now) returned to power. McCully was promptly appointed solicitor general and also made the sole railway commissioner, while still keeping his hand on the editorial desk of the Morning Chronicle. McCully ran the Nova Scotia Railway from 1860 to 1863 with a ruthless eye to saving money. This, rather than that other touchstone, efficiency, guided him. He was in an excellent position for creating enemies and, being blessed with neither tact nor taste, made good use of his opportunities. A doggerel of the time ran:

I am monarch of all I survey,

My will there is none to dispute,

Trains run when I want ‘em to run

And toot when I tell ‘em to toot.

McCully’s railway interests had also ramified into the Intercolonial Railway project. He had urged this in the Chronicle as early as 1855 and periodically afterwards. In September 1861 he was in New Brunswick for negotiations on the Intercolonial; partly as a result of these negotiations and partly as a result of reaction to the American Civil War, a conference on the Intercolonial Railway between Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia was held at Quebec in October 1861; there McCully again represented Nova Scotia. At a similar conference in September 1862, McCully was replaced by William Annand*, the owner of the Morning Chronicle.

It is fair to say that McCully was a difficult man for Howe’s Liberal government to carry. He had little popular appeal; there is good reason to doubt whether he could ever have been elected for a constituency, a fact that Howe was to throw at him in 1867. Howe blamed him, in part at least, for the Liberal defeat at the polls in the general election of 1863, especially because of his bullying administration of the government-owned railway. “Jonathan,” said Howe, “is the kind of fellow that costs more than he comes to. I carried him as long as I could stagger under him.”

In August 1864 the Tupper government chose both Liberal and Conservative delegates to represent the province at the Charlottetown conference. McCully was the leader of the Liberals in the Legislative Council; nevertheless his name was omitted. Only at the last minute, as a result of the withdrawal of John Locke, was McCully’s name suggested by Adams G. Archibald*, leader of the Liberal party. McCully’s contribution at Charlottetown and at Quebec was inconspicuous; it can be roughly documented, but it seems to have been unimportant. His real importance in the confederation movement was his attempt to popularize the Quebec resolutions in Nova Scotia, and to expand the political horizons of Nova Scotians to include the idea of a united British North America.

Up to this time union had not been a particular theme of McCully’s. The Morning Chronicle in 1856 had praised colonial union as “a measure that every thinking man feels is essential. . . . We cannot remain as we are.” But even Howe in those days would have agreed with that. By 1860 McCully was raising massive doubts about the value of a colonial union, as if he were already following Howe’s ideas about some new reorganization of the empire. For McCully, Canada’s expenditure on such projects as canals and the Grand Trunk Railway and her burgeoning population had, by 1860, made it obvious that this province was outdistancing New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, to say nothing of Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland; although the Morning Chronicle would not say flatly that it opposed a colonial union, it felt, on the whole, that Nova Scotia should leave well enough alone (1 Dec. 1860). In any case that project was soon overshadowed by the more immediate prospects (so it was thought) for the Intercolonial Railway, and by the American Civil War. When colonial union appeared again in the Chronicle’s editorials, in 1864, it was still being regarded with distrust, especially so with Canadian talk of a federal union being noised abroad (30 June, 4 Aug., 1 Sept. 1864).

Within three weeks after 1 Sept. 1864, the position of the Halifax Morning Chronicle radically changed. The Charlottetown conference had converted McCully, and not a few others, to confederation. Howe made bitter sport of McCully’s conversion. After Charlottetown, Howe said, McCully returned to Halifax as full of the glory of confederation as a girl newly proposed to. Indeed, Howe added, more than proposed to: seduced. St Paul, said Howe, had been converted by a flood of light; Danaë was converted from a virgin to a strumpet by a shower of gold: “you . . . can judge whether McCully was converted after the fashion of Danaë or St Paul.” All through the autumn of 1864 (though editorials languished somewhat during McCully’s absence at Quebec) the Morning Chronicle threw its heavy weight behind confederation, and especially so in the critical period after McCully had returned to Halifax from Quebec on 10 November. Then on 10 Jan. 1865 came the announcement that McCully was fired from the editorial desk of the Chronicle.

At once the Chronicle swung over on its anti-confederate tack. McCully bought out the old Morning Journal and Commercial Advertiser, christened it the Unionist and Halifax Journal, and for over two years laboured to sell confederation to the Nova Scotians. It was uphill work; and after confederation was approved by the Nova Scotia legislature, in April 1866, McCully gradually eased off. He was a delegate to the London conference of 1866–67, but his strength, as before, lay in his pen. In the pamphlet battle he and Tupper vigorously defended the course Tupper’s government had taken in London in January and February 1867.

Jonathan McCully was appointed to the Senate of the dominion of Canada later that same year. From this point he is gradually overshadowed politically by Tupper, Archibald, and, in 1869, Howe. McCully was bound to support Tupper and the better terms of 1869, but he seems not to have been influential in the negotiations for Howe’s entering the John A. Macdonald* government in 1869. McCully was shrewd enough however to perceive that Canada’s acquisition of the North-West would impose tremendous tasks upon the new confederation. “It has come upon us,” he said in the Senate, “before we are fully prepared for it. We are scarcely organized ourselves. Our own house is not [yet] set in order . . . .”

In 1870 McCully was appointed puisne judge on the Nova Scotia Supreme Court; he had obviously made his peace with Howe, since it was to Howe as well as to Tupper that he owed his appointment. McCully came comfortably to rest on the bench. Here his forthright manner and natural instincts for dispatching business crossed the penchant of Halifax lawyers for talk. McCully won. The backlog of court dockets was thus dispatched with some celerity, which did not endear him to the legal fraternity but won him golden opinions – a refreshing change for McCully – from the public at large. This firmness was joined, as it seemed appropriate it now should be, to a newer impartiality, something for which McCully had not always been conspicuous.

He died at his home on Brunswick Street, Halifax, at the age of 67, leaving a substantial estate of $100,000. He is buried in Camp Hill Cemetery.

McCully was not a remarkable man; one of those people who could not do things by halves, he climbed, not very elegantly, up through colonial society. He disliked humbug or pretence; he had none of those arts himself. He cared little for public opinion; his course on confederation took courage: there were not many who would have done what he did. Yet somehow he remains an unlovely figure. With McCully, instincts answered for ideas, and his advocacy did not always help a good cause. He was in this respect like Charles Tupper, but without Tupper’s cleverness or agility. McCully’s stubbornness and pugnacity, his capacity for work, took him a long way – farther perhaps than his talents really deserved. He was a successful man before confederation became an issue; but it was confederation that made him famous, and gave him the right to this long essay here.

[Up to the present no major collection of McCully papers has been found. There are a few McCully letters in PAC, MG 24, B29 (Howe papers), 1–5, 30–31; MG 26, A (Macdonald papers), 51; MG 26, F (Tupper papers), 1–18; MG 27, I, D8 (Galt papers), 1–4. One can probably assume that most of the leading editorials in the Halifax Morning Chronicle between 1856 and 1865 were written by McCully, and the same can be said for the Unionist and Halifax Journal for 1865 and 1866. His speeches in the Legislative Council of Nova Scotia can be found in the Journals of the proceedings of that body; those in the Senate of Canada, for 1867–68, in Senate debates, 1867–68, ed. P. B. Waite (Ottawa, 1967). The later Senate debates to 1870 have not yet been reprinted and can best be read in the Ottawa Times. McCully’s decisions in the Nova Scotia Supreme Court are in Nova Scotia Supreme Court Reports, VIII–XII (1869–79). For secondary sources see the following: Saunders, Three premiers of N.S.; P. R. Blakeley, “Jonathan McCully, father of confederation,” N.S. Hist. Soc. Coll., XXXVI (1968), 142–81; N. H. Meagher, “Life of the Hon. Jonathan McCully, 1809–1877,” N.S. Hist. Soc. Coll., XXI (1927), 73–114. p.s.w.]

Cite This Article

P. B. Waite, “McCULLY, JONATHAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 17, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mccully_jonathan_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mccully_jonathan_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | P. B. Waite |

| Title of Article: | McCULLY, JONATHAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | February 17, 2026 |