Source: Link

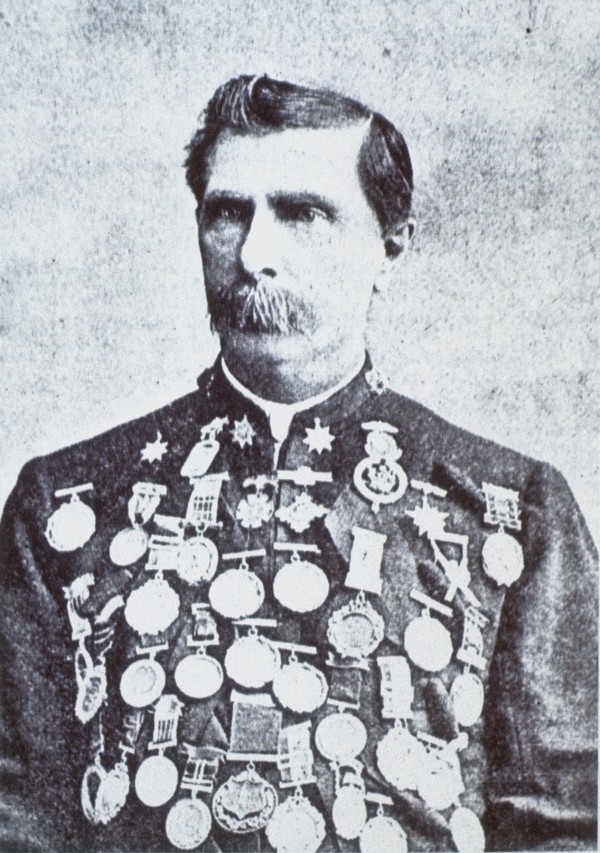

McKINNON, HUGH, constable, detective, athlete, police chief, and office holder; b. 4 May 1843 in Vaughan Township, Upper Canada, son of Martin McKinnon, an immigrant from the Isle of Mull, Scotland, and Flora Lamont; m. 1874 Jennie Morrison Lamont, and they had one adopted daughter; d. 12 Dec. 1903 in Dawson City, Y.T.

The tenth of 11 children, Hugh McKinnon was raised on his parents’ farm in Vaughan, leaving about age 15 for a “year in hard scholastic work,” probably in Chatham. In 1861 or 1862 he moved to Hamilton and was soon articled to his elder brother, David, a lawyer. According to his own account in 1886, though he studied nearly three years he reckoned himself a “born detective” and “hungered for a chance to distinguish himself in police and detective work.”

What he did next is uncertain. By his own, in this case faulty, recollection, he joined the Hamilton police department in June 1863 and later became a detective. Other sources suggest he left his legal studies in 1865 to become a government detective. The 1871 census for Hamilton describes him as a detective, an occupation in which he gained a measure of notoriety. Of particular note were his five weeks in 1876 on the track of the infamous Donnellys of Lucan, Ont. [see James Donnelly*]. Hired in February by a local vigilance committee to build a case against them, he spent some time lolling about a tavern in the “guise of a sporting character,” where he overheard a derogatory remark about the Donnelly family. He pummelled the unwitting offender, thereby gaining the confidence of Michael Donnelly and, he hoped, inside knowledge. He subsequently kidnapped Will Donnelly and his follower William Atkinson and then hung the men by their thumbs to get them to talk. Though he himself would be charged, tried, and acquitted for that action, five Donnellys and several associates were brought to trial in March. The prosecution was successful.

Rarely in the late 19th century did a police officer or a detective gain renown for investigative facility. John Wilson Murray’s reputation derived from self-promotion; McKinnon’s stemmed from his size and aggressiveness. Despite his later emphasis upon strength of character and restraint in policing, the tales of his derring-do always made good copy and focused on other qualities. And small wonder, for he was six feet three inches and 225 pounds with a reputation for prowess in Highland games of strength. Caledonian games had grown in popularity across North America and Scotland [see Roderick McLennan]; it was McKinnon’s good fortune to dominate during their zenith in the 1870s. In 1875, for instance, at the international games in Toronto, he was the “best general athlete.” He then toured the United States; in August the New York World reported the exploits of “the celebrated athlete from Hamilton” in events such as throwing the hammer and the 56-pound weight, putting the stone, and tossing the caber in the games held at Brooklyn. In August 1876 he won the North American championship at Charlottetown; he repeated his performance at Philadelphia the following year, and then retired.

On 5 Feb. 1877 McKinnon was selected over 12 other candidates as chief of police for Belleville, Ont., a city of 11,192 with a seven-man force. One Bellevillian would eulogize him for “herculean strength and plenty of grit” and his fearlessness of gangs. On 8 Oct. 1886 McKinnon was appointed chief constable in Hamilton, an industrial city of 41,712, the second largest in Ontario. On 1 November, at a salary of $1,600, he took over the 44-man force, which was overseen by a board of police commissioners. The city was divided into three sections, each with its own station, sergeant, patrol sergeant, and constables. The constables were required to be British subjects, large in size, “of sound body and mind,” and of “good moral character and habits.” And Hamilton’s new chief constable seemed to exemplify these requirements. There were, as well, four detectives (two of them acting) and two drivers. The chief’s responsibilities included recruitment, discipline, law enforcement, maintenance of records, reports to the board, and direct supervision of “serious” fires and “all riots.”

With a budget of approximately $42,000, McKinnon’s department contained the turbulence typical of city life. Between 1886 and 1892 annual arrests ranged in number from 1,920 to 3,048. The crimes were overwhelmingly petty: of 2,799 arrests in 1888, for instance, 57 per cent were for infractions involving drunkenness, disorderly conduct, vagrancy, assault, and obscene language. Serious crimes were rare (only 1.46 per cent of arrests in 1888). The largely routine nature of policing was reinforced by the department’s responsibility for stray animals, runaway children, and the provision of food and shelter in the police lodging-house.

During McKinnon’s tenure the city expanded both in population (by almost 10,000) and in area. The police force grew to over 50 members, the budget and salaries were increased, a new central station was built (previously the chief had maintained an office at home), a truant-officer was appointed, call-boxes were installed, and a mounted patrol and police benefit fund were established. As well, McKinnon revived the position of sergeant-major or deputy chief and made the two acting detectives permanent. To handle the needs of female prisoners, he arranged with Mrs Martha Lewis to tend them when necessary. In 1894, pressed by local women’s organizations, the board appointed her full-time matron, over the objections of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union that she was a “colored woman.” A further restructuring of the force that year released more constables for street duty. Despite these improvements, McKinnon was not beyond criticism. In 1891 a government detective had upbraided his force for inefficient detective work; the following year the Trades and Labor Council condemned him for providing “special police protection” to stove manufacturers during a strike.

A popular chief and a good administrator, McKinnon was a practical reformer with an aversion to doctrinaire explanations of crime and reform panaceas for its remedy, as his testimony before several commissions in the 1890s reveals. He was, however, overtaken by problems which began on 8 Jan. 1895, when the Hamilton Spectator took public notice of his unexplained absence of five days. It was alleged by Toronto papers (and reported in Hamilton) that he was then in a Toronto hotel with two women, all of them under assumed names. Matters worsened with the revelation of Hamilton impresario T. H. Gould that the women were his wife and her sister. McKinnon returned and denied allegations of immorality, blaming his “painful and deeply humiliating position” on “wine and not women.” The police board and a shocked community none the less judged him guilty of sexual misconduct and adultery; on the 18th the commissioners demanded his resignation. A week later he was gone, and the board awarded his wife three months’ pay.

A disgraced McKinnon remained in Hamilton for several years as a private detective. In 1901 he turned up in Dawson City, where he was appointed, probably by the territory, chief officer to prevent illegal distilleries and the illegal importation of alcohol. A lifelong Liberal, he was James Hamilton Ross*’s campaign chairman in 1902. He became embroiled in controversy when he assaulted his vice-chairman over non-payment of a bill for whisky and cigars. Several months later he died suddenly of a heart attack; his wife and daughter had only recently joined him.

A freemason, a Liberal, a Presbyterian, and a member of various Scottish societies, McKinnon (or the “big man,” as he was often called) symbolized the braw Highland giant of popular imagination, a figure immortalized in The man from Glengarry . . . (1901), the most famous novel of Charles William Gordon* (Ralph Connor). As an athlete, Hugh McKinnon epitomized one aspect of the attempt by late-19th-century Scots to define their heritage; as a policeman, he personified masculinity in a profession which esteemed it.

AO, F 1535, MS 282: 669, 672, 675, 677, 680, 686. HPL, Hamilton city records, RG 10, ser.B, 1889, Manual of the Police Department of the City of Hamilton (Hamilton, Ont., 1889); ser.S: 234–35, 243, 247, 257–58, 260, 331, 355, 375–82. NA, RG 31, C1, 1871, Hamilton, St Andrew’s Ward, div.l: 80; 1881, Belleville, div.2: 30 (mfm. at AO). Daily Morning Yukon Sun (Dawson, Y.T.), 13 Dec. 1903. Daily Times (Hamilton), 17 Dec. 1891; 8 Feb. 1892; 14, 18 Dec. 1903. Hamilton Spectator, 21 Aug. 1875; 10 Feb. 1880; 2 Nov. 1886; 1 March, 26 Sept. 1887; 19 Jan. 1889; carnival ed., August 1889; 10 May 1894; 31 Aug., 14 Dec. 1903; 30 June 1962. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1894, no.21, vol.4, pt.i: 113–21, 162–63. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. Directories, Hamilton, 1862/63; Wentworth County, 1865/66. [H.] O. Miller, The Donnellys must die (Toronto, 1962), 95–102. Ont., Commission appointed to enquire into the prison and reformatory system of Ontario, Report (Toronto, 1891), 277–81. Prominent men of Canada (Adam). J. C. Weaver, Hamilton: an illustrated history (Toronto, 1982), 196–99.

Cite This Article

Robert L. Fraser, “McKINNON, HUGH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mckinnon_hugh_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mckinnon_hugh_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert L. Fraser |

| Title of Article: | McKINNON, HUGH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |