Source: Link

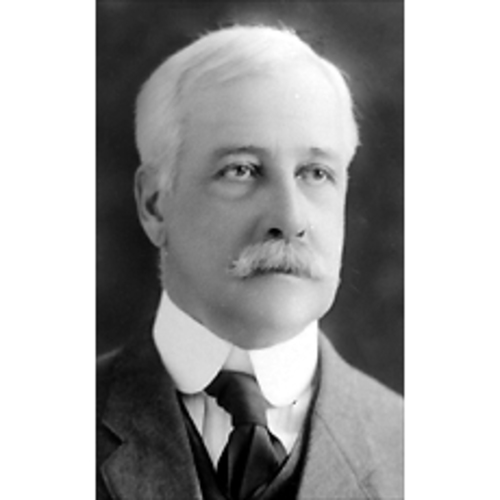

McLENNAN, JOHN STEWART, businessman, historian, author, newspaper publisher, and politician; b. 3 Nov. 1853 in Montreal, eldest son of Hugh McLennan* and Isabella Stewart; m. first 7 April 1881 Louise Ruggles Bradley (d. 1912) in Evanston, Ill., and they had four daughters and one son; m. secondly 7 Jan. 1915 Grace Seely Henop (d. 1928), widow of Robert de Peyster Tytus, in New York, and they had one son; d. 15 Sept. 1939 in Ottawa and was buried in Sydney, N.S.

John Stewart McLennan was a descendant of Scottish immigrants; his paternal grandfather, with parents and siblings, arrived in Lower Canada in 1802 and had settled in Upper Canada by 1803, while his maternal great-grandmother, a widow, and her children landed in Lower Canada in 1816. John’s father co-founded a shipping company in Montreal and Chicago in 1853, moved with his young family to Chicago three years later, and returned to Montreal in 1867, at which time he was, in his son’s words, “a man of substance.”

John attended the High School of Montreal and McGill College, from which he graduated in 1874 with first-rank honours in philosophy and the Dufferin Medal. In 1879 he obtained a second ba from the University of Cambridge in England, having majored in moral sciences. His education gave him a lifelong interest in and appreciation of history and philosophy. The obituary published in the Gazette (Montreal) claimed that his ambition to be a philosophy professor had been thwarted by defective eyesight, yet McLennan’s younger son stated that his father’s vision had been excellent.

There were probably a number of reasons why he entered the world of business rather than academia after returning from Cambridge at the age of 26. He began work in his father’s firm, the Montreal Transportation Company, which dealt primarily with grain. In April 1881 he married Louise Ruggles Bradley. Presumably they had become acquainted during the McLennans’ years in Chicago. The marriage contract was carefully negotiated and very specific about the ownership of assets. Not surprisingly for a relatively affluent wife in the late 19th century, Louise concentrated on her skills as a mother, hostess, gardener, and painter. She would become a gifted watercolourist of Cape Breton and European scenes, signing her works L. B. McLennan.

The couple, now with a daughter, appear to have moved to Cape Breton Island in 1882, although McLennan himself stated in two of his published works that it was 1884. In a biography of his father, he wrote that the relocation took place because Hugh had asked him “to help adjust a difficulty in connection with the International Coal Company, recently bought by my father and some of his associates. This we thought would take only a few weeks.” The nature of the “difficulty” is unknown, but its result was that the McLennans established their home on Cape Breton. He became manager of International Coal’s mine at Bridgeport (Glace Bay) and later managing director of the company. In Sydney he and his growing family lived first in a house called Ridgefield; their next house was named Brookdale. Oral tradition has it that they occasionally performed plays such as Shakespeare’s A midsummer night’s dream.

The Cape Breton coal industry underwent a dramatic transformation in 1893 when Henry Melville Whitney* of Boston, with the backing of the Nova Scotia government, spearheaded the amalgamation of eight collieries, including McLennan’s, into the Dominion Coal Company Limited. The following year McLennan moved to Boston, where he became an executive assistant for the firm. He and his family would live there for the next several years, though they would spend each summer on Cape Breton in the village of Louisburg (Louisbourg), which was emerging as a major coal-exporting centre following the 1895 completion of a rail line connecting Sydney and the coalfields with the village. A key part of the development was the construction of massive coal-piers at the Sydney and Louisburg harbours.

However much work McLennan carried out during the summer months on behalf of Dominion Coal, on his own time he became increasingly captivated by the ruins located at the opposite side of the harbour from the coal-piers. These were the remains of the French fortified town of Louisbourg, which had been taken by the British in 1758 [see Jeffrey Amherst*]. In his first known publication, an entry on Cape Breton Island he co-authored with Robert Murray* for Picturesque Canada (Toronto), he had written that there should be a memorial at the historic site. Walking through the ruins in the 1890s, he must have begun to envision himself writing a history of what was then a little-known vanished settlement. He was not alone in his fascination with the bygone fortress. In May 1895 Acadian author and senator Pascal Poirier protested against a monument planned by the American-based Society of Colonial Wars, and he continued to demand protective government action. Havenside, the house McLennan rented in Louisburg, belonged to another historical enthusiast, fellow industrialist David Joseph Kennelly, who in the early 1900s would stabilize the most prominent parts of the fortress and persuade the Nova Scotia government to pass legislation for preserving the site. The major influence on McLennan, according to his youngest daughter, Katharine*, was Thomas Fraser Draper, the local Church of England archdeacon.

In 1899 McLennan’s life entered a new phase when Whitney and others created the Dominion Iron and Steel Company Limited, which sought to capitalize on Cape Breton’s coal deposits, as well as iron ore in nearby Newfoundland, by building a complex to manufacture steel. McLennan was the first treasurer of the new company, and then a director and effectively general manager. In 1900, not yet 50, he left the conglomerate. It is likely significant that his retirement took place one year after the death of his father. Hugh McLennan’s passing may have prompted his son to end a career he was not passionate about to work on endeavours of greater personal interest. John also had the example of his younger brother William*, a notary who had become a well-known translator and author of historical novels.

After leaving the coal and steel industry, McLennan became an entirely self-funded researcher on Louisbourg. With Louise, and sometimes their children, he would spend several winter months each year in Europe. Much of his time was passed in London and Paris, locating maps, plans, and documents on the French era at Louisbourg. In 1908 he gave a lecture on the fortress to the Nova Scotia Historical Society, which was published in the following year as A notable ruin. He wrote a chapter on the same topic for the first volume on New France in the series Canada and its provinces (Toronto, 1913). In the same year he sent off an almost-completed book-length manuscript to the Champlain Society, but it was rejected because it was a long narrative history rather than a collection of period documents. The book finally appeared in 1918 as Louisbourg from its foundation to its fall, 1713–1758 (London). It remains a fundamental work on the chronological history of the French colonial town.

Another new career for McLennan after he left the coal and steel industry in 1900 was as a newspaper publisher. In 1904 he had purchased the Sydney Post, associated with the Conservative Party. In 1933 he would merge the paper with its Liberal rival, the Sydney Record, to establish the independent Sydney Post-Record (succeeded by the Cape Breton Post). McLennan took his responsibilities as a newspaper owner seriously, and hoped to exert a positive influence on his community. In his later years, when he was in residence in Sydney, he would pay a daily visit to the paper’s office.

The period of World War I was a time of great change for McLennan, as it was for most Canadians. He became president of the Cape Breton branch of the Canadian Patriotic Fund, and would serve on the national executive until it wrapped up in 1937. His wife, Louise, had died of a ruptured appendix in 1912, and in January 1915 he married Grace Seely Henop, an accomplished linguist and writer and the widow of Egyptologist Robert de Peyster Tytus. In May, McLennan learned that his son, Hugh, had died in the second battle of Ypres. Soon afterwards, he wrote to Prime Minister Sir Robert Laird Borden to ask if he could do more to help the war effort. Samuel Hughes*, the minister of militia and defence, received a letter in which McLennan urged the government to make provisions to defend Sydney, with its large harbour and steel-making facilities. Borden appointed him to the Military Hospitals Commission established by order in council on 30 June 1915 and chaired by James Alexander Lougheed*; historians Desmond Morton and Glenn Wright have described him as one of the commission’s “hardest-working members.” On 10 Feb. 1916 McLennan, a long-time Conservative, was named to the Senate. One of his particular concerns was the federal government’s preparation of the country for the war’s aftermath. He foresaw that economic development, reintegration of veterans (he was convinced that retraining would be essential for the able-bodied as well as the disabled), and Canada’s changing relationship with Great Britain would all require attention and commitment. Although he rarely spoke during proceedings in the Red Chamber, he served on several committees, presiding over one that dealt with government function and process. In his 1919 report on the machinery of government, he argued the need for increased effectiveness to counter the enormous challenges facing the country, and warned “the time will come when the people of Canada will not tolerate in its government a degree of efficiency falling far below that to which they are accustomed in any other form of corporate action.”

Having lost his son in 1915, McLennan learned, in 1918, that his younger brother Bartlett, a Montreal businessman, had been killed in the battle of Amiens. Over the next several years, he endured the disintegration of his second marriage, which culminated in a divorce in 1927. The settlement stipulated that he could see his son, John Stewart Jr, only twice a year for short periods. Publicly, McLennan was a prominent figure in eastern Canada throughout the 1920s and 1930s. McGill University awarded him an honorary lld in 1923; that winter he gave a series of public lectures at New Brunswick’s Mount Allison College on “history and present problems.” He continued to maintain a partisan presence in the Senate; for instance, he opposed the 1926 Old Age Pensions Bill of William Lyon Mackenzie King*’s Liberal government. During the summers at Petersfield, the family home base in Sydney since 1901, he hosted luminaries such as aeronaut Frederick Walker (Casey) Baldwin*, poet Charles George Douglas Roberts*, medical missionary Wilfred Thomason Grenfell, Lord and Lady Baden-Powell, British prime minister James Ramsay MacDonald, and governors general Lord Byng, Lord Willingdon [Freeman-Thomas*], and Lord Tweedsmuir [Buchan]. Fulfilling his responsibilities as a senator, McLennan occasionally wrote to Prime Minister Arthur Meighen* on a range of issues, as he had done earlier with Borden, and as he would do to a lesser degree with Richard Bedford Bennett*. Both Meighen and Bennett also visited Petersfield.

McLennan’s in-depth familiarity with the history of Louisbourg meant that he became a key resource person for the dominion parks branch and its advisory body, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, when the government began to acquire the ruins in the 1920s. McLennan was an active lobbyist for the site’s protection and promoted its educational value, having argued in A notable ruin that it was possible “to reconstruct the city as it was” and that such a task would be “only a question of intelligence and outlay.” He believed that all work done at Louisbourg should be appropriate to the first half of the 18th century, and donated many maps, plans, and historical objects to the museum that would be built in 1935–36. He opposed the creation of any monument that emphasized the reason for the fortress’s destruction, writing “I think we want to avoid the suggestion that any work we do marks the victory of the British over the French.” He hoped that a preserved Louisbourg would promote a sense of Canadian identity.

When he was in his eighties, the Montreal Standard described McLennan as “one of the best-looking men in the Red Chamber, dowered with the courtly manners and charm of a statelier age … he fittingly represents the most polished and cosmopolitan type of Canadian.” After his death from pneumonia in 1939, one of his friends, Dr John Clarence Webster*, closed the obituary he wrote for the Royal Society of Canada, of which McLennan had also been a member, with the following: “Few men in Canadian business life have equalled Senator McLennan in combining business acumen and enterprise with long-continued cultivation of mind and absorption in the arts, literature, or other spheres of interest not concerned with material considerations.”

John Stewart McLennan’s second son said that his father’s wish was to have a “useful, successful and honored career,” which he appears to have done. Best known for the second half of his life, especially his contributions as the historian of Louisbourg, McLennan dreamed that there would one day be a reconstructed French fortified town. This vision was not achieved until after his death, but the principles he enunciated have become guiding rules at many heritage projects. He held that preservation work should be based on research and directed by those with expertise, and that it is posterity and not present-day concerns (such as political factors) that determine the merit of the work.

Katharine McLennan donated many works from her father’s library to Dalhousie University. A painter and philanthropist, she carried on her father’s involvement with Louisbourg, serving as honorary curator of its museum until the 1960s. John Stewart McLennan Jr became a distinguished American pianist and composer.

There is no complete list of John Stewart McLennan’s writings. His first known publication, co-authored with Robert Murray, is “Cape Breton,” in Picturesque Canada: the country as it was and is, ed. G. M. Grant (Toronto, 1882–[84]), 2: 841–52. The following are McLennan’s most important subsequent works: Screening of soft coal (n.p., [1887?]); A notable ruin, Louisbourg: a paper read before the Nova Scotia Historical Society, November 10th, 1908 ([Halifax], 1909); “Louisbourg: an outpost of empire,” in Canada and its provinces: a history of the Canadian people and their institutions …, ed. Adam Shortt and A. G. Doughty (23v., Toronto, 1913–17), 1: 201–27; The Canadian current, 1850–1914: per angusta ad augusta (Sydney, N.S., 1915); What the military hospitals commission is doing (n.p., 1918; copy in the Sir Robert Borden fonds at LAC, R6113-0-X); Louisbourg from its foundation to its fall, 1713–1758 (London, 1918; 4th ed., Halifax, 1979; repr. 1983); “History and present problems,” Argosy (Sackville, N.B.), 2 (1924), no.2: 77–132; and Hugh McLennan, 1825–1889 (Montreal, 1936). He was also responsible for the Senate’s Report of the special committee on machinery of government (Ottawa, 1919) and Report of the special committee on the fuel supply of Canada together with the evidence received by the committee (Ottawa, 1923).

Arch. of the Fortress of Louisbourg (Louisbourg, N.S.), File Univ.-JSMCL. Cape Breton Regional Library (Sydney), McLennan coll. Cape Breton Univ., Beaton Instit. (Sydney), MG 9.34 (Senator John S. McLennan). LAC, R5747-1-X, vols.109–1100, 1923–67; R6113-0-X; R11336-o-7 (mfm.); R14423-0-6. N.B. Museum (Saint John), John Clarence Webster fonds, corr. from Senator J. S. McLennan, Sydney, 1921–38. Private arch., A. J. B. Johnston (Halifax), Interview with Eldie Mickel. Cape Breton Post (Sydney), 26 May 1984. Gazette (Montreal), 16 Sept. 1939. Montreal Standard, 7 Nov. 1936. New York Times, 8 Jan. 1915. Gordon Brinley [Kathrine Gordon Sanger Brinley], Away to Cape Breton (New York, 1940). Brian Campbell, with A. J. B. Johnston, Tracks across the landscape: the S&L commemorative history (Sydney, 1995). The Canadian Patriotic Fund: a record of its activities from 1914 to 1919, comp. P. H. Morris ([Ottawa?, 1920?]). Canadian Patriotic Fund: a record of its activities from 1924 to 1929 ([Ottawa?, 1929]). Canadian Patriotic Fund: a record of its activities from 1929–1937 and covering the period from August, 1914 to March 27, 1937 ([Ottawa?, 1937?]). Cape Breton Regional Library, “The McLennans of Petersfield”: www.cbrl.ca/mclennans/index.html (consulted 4 July 2013). Yvonne Fitzroy, A Canadian panorama (London, [1929]). H. H. Howe, The gentle Americans, 1864–1960: biography of a breed (New York, [1965]). A. J. B. Johnston, “Into the Great War: Katharine McLennan goes overseas, 1915–1919,” in The island: new perspectives on Cape Breton history, 1713–1990, ed. Kenneth Donovan (Fredericton and Sydney, 1990), 129–44; “John Stewart McLennan, 1853–1939,” [foreword], in J. S. McLennan, Louisbourg from its foundation …, (4th ed.), iv–v; “Lady artists of Cape Breton: Louise Bradley McLennan and Hetty Donne Kimber,” Canadian Collector (Toronto), 21 (1986), no.2: 45–47; “Louisbourg: the twists of time,” Beaver (Winnipeg), outfit 316 (summer 1985), no.1: 4–12; “Petersfield: storied past to be preserved in new park,” Atlantic Advocate (Fredericton), 173 (1982–83), no.7: 44–45 (repr. in Cape Breton Post, 7 May 1983); “Preserving history: the commemoration of 18th century Louisbourg, 1895–1940,” Acadiensis, 12 (1982–83), no.2: 53–80; “Remembering Louisbourg, 1758–1961” (exhibit texts, 1981–82); “A vanished era: the Petersfield estate of J. S. McLennan, 1900–1942,” in Cape Breton at 200: historical essays in honour of the island’s bicentennial, 1785–1985, ed. Kenneth Donovan (Sydney, 1985), 85–105. Desmond Morton and Glenn Wright, Winning the second battle: Canadian veterans and the return to civilian life, 1915–1930 (Toronto, 1987). Prominent people of the Maritime provinces (Montreal, 1922). J. C. Webster, “John Stewart McLennan,” RSC, Trans., 3rd ser., 34 (1940), proc.: 115–16. Who’s who and why, 1917/18–1921. Who’s who in Canada, 1922–1938/39.

Cite This Article

A. J. B. Johnston, “McLENNAN, JOHN STEWART,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 8, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mclennan_john_stewart_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mclennan_john_stewart_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | A. J. B. Johnston |

| Title of Article: | McLENNAN, JOHN STEWART |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2014 |

| Year of revision: | 2014 |

| Access Date: | February 8, 2026 |