Source: Link

McPHAIL, ALEXANDER JAMES, farmer, office holder, and agrarian leader; b. 23 Dec. 1883 in Paisley, Ont., son of James Alexander McPhail and Elizabeth Menzies; m. 5 Jan. 1927 Marion Grenfell Baird (1904–37) in Springfield, Mass., and they had one son; d. 21 Oct. 1931 in Regina.

The move west and loss of both parents

Alexander James McPhail was born into what his sister Elizabeth characterized as an “intensely religious” Presbyterian farming family (they became Baptists because there were no Presbyterian churches where the family settled). Their parents were Highland Scots, “full of rugged health,” who had immigrated as adults. It must, therefore, have been a shock when their father, James McPhail, developed tuberculosis in 1898. Treatment options favoured dry air, so James mortgaged his Ontario farm and the family moved west to Minnedosa, Man., but he died not long after, in 1900. His wife, who had also contracted the disease, followed in 1903. Alexander, not yet 20 and the eldest, and his sister Annie, who was four years younger, found themselves heads of the household, in charge of their siblings.

Heeding their mother’s last request to keep the family intact, the eldest McPhail children agreed to farm together. Alexander took a homestead in 1904 near Newdale, but soon sold it and joined his brothers and grandmother, who had settled near Bankend and Ladstock, in the Touchwood Hills in what became the province of Saskatchewan in 1905.

McPhail’s was a family in which, according to historian Garry Fairbairn, “the intellectual world often took precedence over physical comforts.” He became a lifelong learner and keen debater who devoured the works of Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas as well as articles in the Manitoba Free Press and the Montreal Family Herald and Weekly Star at the local library. To finance the schooling of his siblings, McPhail sold the Ontario farm. In the winter of 1908–9 he furthered his own education by enrolling at the Manitoba Agricultural College in Winnipeg, where he worked as assistant business manager for the school’s paper, the M.A.C. Gazette.

The First World War and new perspectives on prairie agriculture

McPhail returned to farming, and in 1913 he joined the Saskatchewan public service as a weed inspector in the Department of Agriculture. When war broke out a year later, he shepherded a shipment of horses to Britain on behalf of the government. He attempted to enlist in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1915 but was declared “undesirable,” perhaps, as Fairbairn suggests, because he was suffering from stomach ailments. Interest in domestic animals led McPhail to move to the Department of Agriculture’s livestock branch, where he worked under Paul Frederick Bredt, the livestock commissioner. Late in the war the German-born Bredt was forced to resign because of his nationality. McPhail followed suit in protest.

Having left the government on 9 Feb. 1918, he went into partnership with his brother Hugh Duncan. They traded pigs, horses, and cattle, with Alexander often taking them to market in Winnipeg. Travelling across the west, he witnessed the plight of others far beyond the borders of his own farm. He became increasingly concerned with the problems of prairie agriculture and was drawn to the Progressive Party led by Thomas Alexander Crerar*. McPhail also began attending meetings of the Saskatchewan Grain Growers’ Association (SGGA) [see Frederick William Green*] despite having little experience with wheat. In 1922 he was elected secretary of the association. McPhail found himself vaulted, in the words of journalist Daniel Winters, into the orbit of “powerful characters and personalities” who were intent on changing western Canadian agriculture.

Wheat pools and the promise of the cooperative model

A committed adherent of the cooperative model, McPhail became a major promoter of wheat pools, which offered producers an alternative way to sell their wheat. Participating farmers would no longer have to play the perennial guessing game of when to market their crop; they got the same price as all other pool members, no matter when they fulfilled their delivery contract. Yet pools did not shield farmers from fluctuating wheat prices, and although some members may have received a better price for their wheat than neighbours who had not joined the pool, they were still at the mercy of international markets.

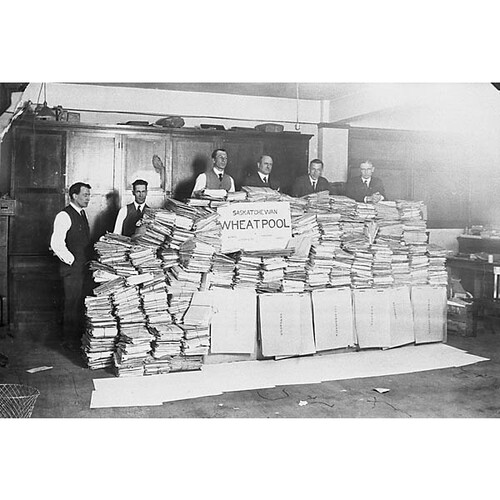

Between 1923 and 1924 pools formed in Alberta, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan, thanks in part to the influence of American activist Aaron Leland Sapiro. In 1924 McPhail was elected the first president of the Saskatchewan Co-operative Wheat Producers (commonly known as the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool, which would become its official name in 1953). He also served as the head of the Central Selling Agency, the interprovincial organization that marketed grain purchased by the three pools. Henry Wise Wood*, head of the United Farmers of Alberta and a strong supporter of wheat pools, had insisted that the agency presidency go to McPhail; Wood became vice-president.

Cooperatives, McPhail believed, worked only when they were voluntary. His position soon led to conflict with the pool’s board members and with Sapiro, who wanted to reduce the pool’s vulnerability by making membership compulsory. By controlling the entire Canadian wheat crop, they insisted, farmers would fare better collectively in the world marketplace. Opponents, like McPhail, maintained that a mandatory enrolment of 100 per cent would weaken the voluntary, cooperative spirit behind the movement and incur the resentment of more traditional, independently minded farmers. Sapiro’s position also challenged McPhail’s sense of democratic freedom, and he vented in his diary that Sapiro was “the most dangerous man in the Co-operative movement.”

As well, the board and Sapiro supported the acquisition of costly grain elevators. McPhail opposed this move because “our primary objective is to sell wheat and everything else is incidental to that.” Having failed to prevent the wheat pool’s 1926 purchase of elevators [see George Langley], McPhail took solace in the importance of democratic decision making. “Democracy is a great institution,” he wrote in December 1925, “but on account of the men thrown up sometimes, its institutions are very often in a very perilous position.… I have still great faith in the common sense of the average man.”

Setbacks and the Great Depression

McPhail viewed himself as one of the “trusted servants” of his “brother growers.” He spent much of his time in lobbying, writing, and conducting meetings. To help spread the pool’s message, he also supported the Western Producer (Saskatoon), one of the most important farmers’ publications in Canada. No amount of advocacy, however, could save the fledgling wheat pool or its selling agency from the October 1929 stock-market crash.

For the 1929–30 crop year, the three prairie pools had set the payment at a dollar per bushel on the assumption that the final price for wheat would be approximately $1.50. But then the international price began its downward slide. To their horror, the pools found that the grain they had received was not worth even the initial price; they had overpaid producers by $23 million. Banks, which had lent the money for the payment to farmers, started to panic. The three prairie governments, recognizing the importance of the pool network to the regional economy, promised to back the pools’ loans at a meeting in Regina in December 1929.

The reprieve from certain bankruptcy was short-lived, however, particularly since the pool’s first payment for 1930–31 (only 70 cents per bushel) was still too high as the financial crisis worsened. Ottawa agreed to bail out the pools, but on federal terms. With the wheat pool’s viability soon in doubt, McPhail tried desperately to appease its creditors. “Everything is tottering,” he confided to his diary on 14 November 1930. “It is gall and wormwood to have to do as you are told by a bunch of bankers who are quite ignorant of the biz.” Prime Minister Richard Bedford Bennett* insisted that the pools cease operating; they could continue as cooperative elevator companies. He also backed John Irwin McFarland*, a respected former private grain dealer, to become general manager of the pool’s central selling agency, in charge of marketing its wheat. One of McFarland’s first acts was to close the agency’s overseas offices. He then let all its employees go, effectively dismantling the organization – much to McPhail’s displeasure. These setbacks for the prairie pools proved extremely disheartening and reignited the debate over whether there should be a national, compulsory pool.

In 1949 the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool would triumphantly repay the province two years ahead of schedule. But Alexander McPhail did not live to see success rise from the ashes. Buffeted and bruised by so many bitter fights, and devastated by the effects of the Great Depression on the market and loss of cooperative power to government and creditors, he died at the age of 47 from a blood clot following a successful appendectomy. He left a widow, Marion Grenfell, who had been his secretary at the SGGA, and their young son.

Legacy

An intensely private man, McPhail kept a diary of his daily life – a legacy passed down by few other Canadian farmers. It describes the everyday toil of wresting a living from a farm and his certainty that cooperation on a democratic model would be the best way forward for western farmers. Over 40 years after McPhail’s death, Helgi Hornford, a former fieldman with the Saskatchewan pool, remained impressed by his forceful and determined presence, his integrity, and his character: “You could tell that he was a real good man. You could tell that he was a co-operator through and through.”

What little is known about Alexander James McPhail’s early life comes from an undated letter his sister Elizabeth wrote to historian Harold Adams Innis*, presumably when he was editing The diary of Alexander James McPhail (Toronto, 1940) for publication. This edited diary contains excerpts from McPhail’s writings and speeches, including his address before the Second International Co-operative Wheat Pool Conference in Kansas City in 1927.

Ancestry.com, “Ontario, Canada births, 1832–1917,” Alexander James McPhail, South Bruce, 23 Dec. 1883. LAC, R190-84-2-E (Dept. of the Interior, Lands Patent Branch, letters patent), Gladstone McPhail, Duncan McPhail; RG 150, Acc. 1992-93/166, box 7168-3; R233-37-6, Man., dist. Marquette (9), subdist. Odanah (N), div. 1: 2. Univ. of Man. Arch. & Special Coll. (Winnipeg), Faculty of agriculture fonds. Univ. of Toronto Libraries, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, ms coll. 00054 (Alexander James McPhail papers). Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, 21 Oct. 1931. Winnipeg Tribune, 5 Jan. 1927, 21 Oct. 1931. Canadian Plains Research Center, Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan (Regina, 2005). G. L. Fairbairn, From prairie roots: the remarkable story of Saskatchewan Wheat Pool (Saskatoon, 1984), 47. Historica Can., Canadian encyclopedia. [J. W.] G. MacEwan, “Wheat pool pilot: Alexander James McPhail,” in his Fifty mighty men (special ed., Saskatoon, 1982). Univ. of Sask., Univ. Arch. & Special Coll. and Centre for the Study of Co-operatives, “Leaders – A. J. McPhail,” in Saskatchewan Wheat Pool: a history in pictures (2019). Daniel Winters, “A. J. McPhail – president of wheat producers co-op sought protection for farmers,” Western Producer, 27 Dec. 2007.

Cite This Article

Merle Massie, “McPHAIL, ALEXANDER JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcphail_alexander_james_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcphail_alexander_james_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Merle Massie |

| Title of Article: | McPHAIL, ALEXANDER JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2026 |

| Year of revision: | 2026 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |