Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

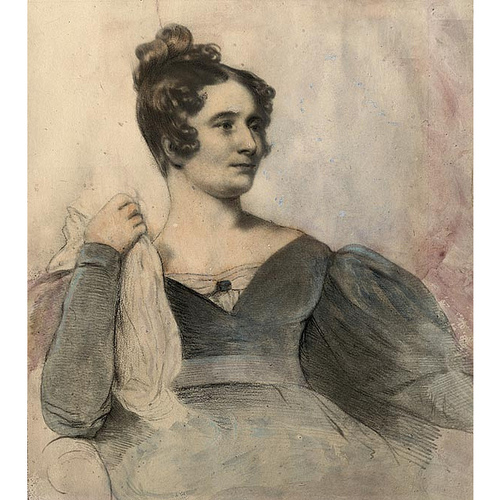

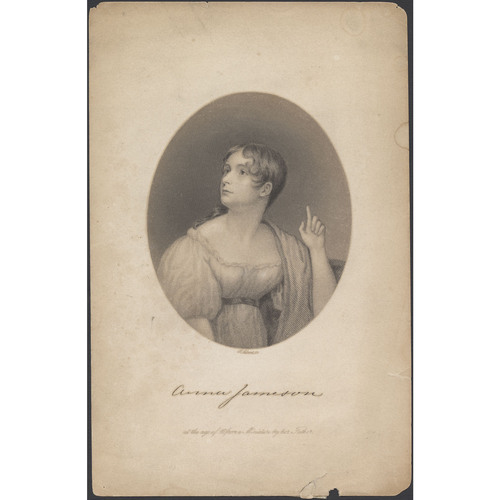

MURPHY, ANNA BROWNELL (Jameson), writer, feminist, and traveller; b. 19 May 1794 in Dublin; m. 1825 Robert Sympson Jameson; they had no children; d. 17 March 1860 in Ealing (London).

Anna Brownell Murphy was the eldest of five daughters of Denis Brownell Murphy, an Irish miniaturist and portrait painter. In 1798, just before the rebellion in Ireland, Murphy, a vociferous and therefore endangered patriot, immigrated with his English wife and daughter Anna to England. He settled in 1802 at Newcastle upon Tyne, where he prospered sufficiently to send for the two daughters who had been left behind in Ireland. By 1806, when he moved his family to London, there were five daughters and Murphy was enjoying a modest success as a miniaturist. In 1810, as “Painter in Enamel” to Princess Charlotte, daughter of the Prince and Princess of Wales, he began making miniature copies of Peter Lely’s portraits of the ladies of the court of Charles II, hoping to sell these to his patroness. Princess Charlotte died in 1817, the miniatures were unsold, and Murphy’s fortunes speedily waned.

Anna was the most precocious of the children, particularly clever in learning languages, always ambitious to excel, and, from an early age, anxious to assume a part of the responsibility for the family’s welfare. For a time the Murphys could afford a governess, whom Anna remembered as “one of the cleverest women I have ever met.” Before the family moved to London, however, she had gone; henceforth the sisters’ education progressed with Anna in charge. In the words of her niece Gerardine Macpherson, she educated herself “chiefly at her own will and pleasure. . . . She worked hard, but fitfully at French, Italian and even Spanish.”

In 1810, when Anna was 16, she took up her first post as governess to the four small sons of the Marquis of Winchester, leaving in 1814. In 1819 she began an engagement with the Rowles family which was to lead to her first successful book. She accompanied them to the Continent in 1821, travelling in luxury “à la Milor Anglais” through the Low Countries and into Italy. She quickly became an avid traveller, a connoisseur of art galleries, and an intrepid sightseer: “I had an opportunity of witnessing a most magnificent spectacle, an eruption of Mount Vesuvius and ascended the mountain during the height of it.” Back in England in 1822, and without the capital to start the school she had been planning, she became governess to the children of Edward John Littleton, afterwards 1st Baron Hatherton, a post she retained until her marriage to Robert Sympson Jameson of Ambleside in 1825. During these years she wrote two works for young children, “Much coin, much care,” a drama (published 1834), and “Little Louisa,” a vocabulary of useful words.

Robert Jameson had courted Anna Murphy since before her Continental trip in 1821. There was a strange intermittent incompatibility between them which both parties and Anna’s family realized. However, there were also strong attractions, particularly a common love of literature and of literary society. Jameson encouraged his wife in the writing of her first travel book, published anonymously in 1826 under the title A lady’s diary and then as Diary of an ennuyée. It was a romanticized and fictionalized version of her European trip ending with the death of its heart-broken narrator and heroine. Heavily influenced in plan and content by Mme de Staël’s popular novel Corinne (1807), the book was a sentimental Childe Harold’s journey for impressionable and adventure-hungry young ladies. It was a great success and when Mrs Jameson was shortly revealed as its author she became the “lioness” of the hour in London society.

By 1829, when Robert Jameson left England for an appointment as chief justice of Dominica, Anna was making no secret of unhappiness in her marriage. She was increasingly committed to a life of travel and writing. The loves of the poets was published in 1829 and Memoirs of celebrated female sovereigns in 1831. These books (The beauties of the court of King Charles the Second, with her text for her father’s miniatures, was to follow in 1833) were designed for the growing numbers of women who were voracious in their appetite for entertaining and pleasantly improving reading material. From the beginning of her writing career Anna Jameson stressed the importance of better education for women. She was a determined, though conservative, early feminist, one of the many in her generation who were increasingly vocal about their rights in law and their needs and opportunities in society.

In 1832 her Characteristics of women, a discussion of Shakespeare’s heroines, made her name on the Continent and in America as well as in England. On a trip to Germany after its publication she was the centre of an admiring group which included Johann Ludwig Tieck and August Wilhelm von Schlegel, and she began a lifelong friendship with Ottilie von Goethe, the poet’s daughter-in-law. Her Visits and sketches at home and abroad (1834) is the record of a Continental trip taken in 1829, in the company of her father and Sir Gerard Noel Noel, a wealthy and eccentric aristocrat, and another in 1833. For it, as for all her future works, Anna Jameson was now assured of a reading public; she had become an established author.

In the fall of 1836 she reluctantly came to Toronto to join her husband who in 1833 had become attorney general of Upper Canada. Jameson was hoping to be appointed to the vice-chancellorship of the Court of Chancery, the highest legal post in the province. He had begun to build a house in which to receive his wife, and he wanted her presence to confirm his own social stability at this crucial time in his career. For Anna’s part, she had long since accepted their emotional incompatibility; furthermore she thoroughly enjoyed the life of a successful writer and cosmopolitan traveller with many friends in England and on the Continent. Life in Upper Canada held no attractions whatever for her. She came grudgingly, only because both social and financial necessity dictated that she should. She had heavy responsibilities in the support of ailing parents and unmarried sisters. She needed Jameson’s good will; had he wished, he could, by law, have claimed her earnings. She hoped instead for his financial assistance.

She sailed from London on 8 Oct. 1836, landed at New York in early November, and arrived in Toronto, after an arduous eight-day journey, in mid December. Her few weeks in New York, where she was much sought after and entertained by the literati, provided a radical contrast to her lonely arrival in Toronto. Her first journal entry in Upper Canada, dated 20 December, sets the tone of her wintry impressions: “A little ill-built town on low land, at the bottom of a frozen bay. . . . I did not expect much; but for this I was not prepared. . . . I see nothing but snow heaped up against my windows, not only without but within; I hear no sound but the tinkling of sleigh-bells and the occasional lowing of a poor half-starved cow.” Jameson’s appointment as vice-chancellor was confirmed and the couple moved in March into the house he had built. Anna remained in Toronto until early June 1837. Then she set out on a tour which took her through the southwestern part of the province – Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake), Hamilton, London, Port Talbot – and to Detroit – then by steamer to Michilimackinac (Mackinac Island, Mich.) and by open boat to Sault Ste Marie (Ont.), and back by way of Lake Huron and Manitoulin Island. She arrived in Toronto in mid August, reporting to her family that “the people here are in great enthusiasm about me and stare at me as if I had done some most wonderful thing; the most astonished of all is Mr. Jameson.” In September 1837 she left Upper Canada, having arrived at a separation agreement with her husband. She spent some months in the United States, and after she had received and signed the final separation papers she sailed for England in February 1838.

Winter studies and summer rambles in Canada, published in London in 1838, is the record of both her winter in Toronto and her summer trip. In “Winter studies,” written in the form of a journal to an absent friend, she intersperses notes on the frigidity of weather and society with lively characterizations of the few people, James FitzGibbon*, for instance, who took her fancy: “Colonel F. is a soldier of fortune – which phrase means, in his case at least, that he owes nothing whatever to fortune, but every thing to his own good heart, his own good sense, and his own good sword. He was the son, and glories in it, of an Irish cotter, on the estate of the Knight of Glyn. At the age of fifteen he shouldered a musket, and joined a regiment. . . . The men who have most interested me through life were all self-educated, and what are called originals. This dear, good F. is originalissimo.” Her sharp and witty analysis of the current political factions, in those months rising toward the crisis of the rebellion, begins with a general indictment: “There reigns here a hateful factious spirit in political matters, but for the present no public or patriotic feeling, no recognition of general or generous principles of policy: as yet I have met with none of these. Canada is a colony, not a country.” To offset her intellectual deprivation she determined to translate a manuscript volume of Johann Peter Eckermann’s conversations with Goethe, and she included her musings on it in her journal.

In “Summer rambles” we see Anna at her best, an intrepid, adaptable, enthusiastic explorer, intensely interested in everyone she meets (Colonel Thomas Talbot being a lively example) and everything she experiences. She was delighted to be “the first European female” to shoot the rapids at the Sault, her companion a part-Indian friend, George Johnston. Escorted homeward down Lake Huron in a bateau rowed by four voyageurs, she was awestruck by the unspoiled beauty of the islands around her, “fairy Edens” as she called them: “I remember we came into a circular basin, of about three miles in diameter, so surrounded with islands, that when once within the circle, I could perceive neither ingress nor egress; it was as if a spell of enchantment had been wrought to keep us there for ever.” She spiced her account of the tour with well-authenticated Indian lore gathered both from her reading and from her visit with Henry Rowe Schoolcraft and his family at Michilimackinac. The comparative position of women among whites and Indians is also a major theme, as is the need for women’s education according to their various spheres of opportunity. Anna Jameson’s is a vastly different account of Upper Canada from those of Susanna Moodie [Strickland*] or Catharine Parr Traill [Strickland*]: she was a bird of passage, a writer who already knew that she had a cosmopolitan audience for her work; the Stricklands were immigrant pioneers who wrote to instruct and, in Susanna’s case, to warn others who would follow them.

The critical and popular success of Winter studies and summer rambles reinforced Anna’s reputation as a writer – but Robert Jameson, she reported, was “displeased.” In the last two decades of her life, her massive compendium of Christian art was her major work: Sacred and legendary art (1848), Legends of the monastic orders (1850), Legends of the Madonna (1852), and The history of Our Lord (1864), the last completed after her death in 1860 by her friend Elizabeth Rigby, Lady Eastlake, the wife of Sir Charles Lock Eastlake, director of the National Gallery. The series was lavishly illustrated by her own drawings and etchings, and by those of Gerardine Macpherson, her niece. In 1855 Anna had given public lectures on working opportunities for women, and throughout her final years she acted as mentor and adviser to a group of young women, including Emily Faithfull, who began the English Woman’s Journal, and Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, a founder of Girton College. Her close friendship with Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning was one of the mainstays of her later years. Shortly after her death Harriet Martineau, a well-known English traveller and author, referred to her as the “accomplished Mrs. Jameson . . . a great benefit to her time from her zeal for her sex and for Art.” Her works, particularly the many editions of Characteristics of women and Sacred and legendary art, helped to form and direct popular taste in England and America, both in her own day and considerably beyond it. In Canada, Winter studies and summer rambles has remained a classic among our travel journals.

The popularity of Mrs Jameson’s Winter studies and summer rambles in Canada is attested to by numerous Canadian and foreign editions; the original text (3v., London, 1838) was reprinted in Toronto in 1972. Further bibliographic information on her writings is available in the National union catalog and the British Museum general catalogue. The author’s biography, Love and work enough; the life of Anna Jameson ([Toronto], 1967), includes a comprehensive list of sources. Some of Mrs Jameson’s correspondence has been published, in Letters of Anna Jameson to Ottilie von Goethe, ed. G. H. Needler (London, 1939), and Anna Jameson: letters and friendships (1812-–1860), ed. [B. C. Strong] Mrs Steuart Erskine (London, 1915).

DNB. Gerardine [Bate] Macpherson, Memoirs of the life of Anna Jameson (London, 1878). Marian Fowler, The embroidered tent: five gentlewomen in early Canada . . . (Toronto, 1982). Ellen Moers, Literary women (Garden City, N.Y., 1976). A. M. Holcomb, “Anna Jameson: the first professional English art historian,” Art Hist. (London), 6 (1983): 171–87. Clara [McCandless] Thomas, “Anna Jameson: art historian and critic,” Woman’s Art Journal (Knoxville, Tenn.), 1 (1980): 20–22. Leslie Monkman, “Primitivism and a parasol: Anna Jameson’s Indians,” Essays on Canadian Writing (Downsview [Toronto]), no.29 (summer 1984): 85–95.

Cite This Article

Clara Thomas, “MURPHY, ANNA BROWNELL (Jameson),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/murphy_anna_brownell_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/murphy_anna_brownell_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Clara Thomas |

| Title of Article: | MURPHY, ANNA BROWNELL (Jameson) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |