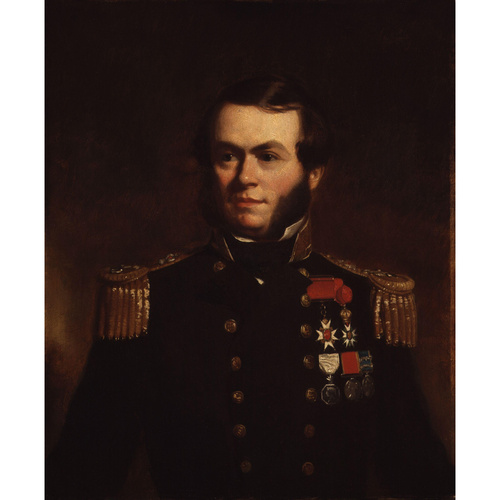

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

OSBORN, SHERARD, naval officer, Arctic explorer, and author; b. 25 April 1822 in England, son of Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Osborn of the Indian army, and of Eliza Todington; d. 6 May 1875 in London, Eng.

Sherard Osborn, nominated first class volunteer in the Royal Navy by Captain William Warren on 30 Sept. 1837, began his career with two long voyages. The first, in 1838–13, was on Warren’s ship hms Hyacinth to the Far East, where he took part in a campaign against Malay pirates in Siam (Thailand) and in Britain’s first Chinese war at Canton and Shanghai. The second voyage, in 1844–48, took him to the Pacific on board hms Collingwood. He was promoted lieutenant on 4 May 1846. Between the two voyages, he spent some months as mate on hms Excellent at Portsmouth, where he studied gunnery. He profited greatly from these years; his commanding officers cultivated his enthusiasm and talents, and Warren in particular set him an example as a diligent officer and a sympathetic commander.

After leaving Collingwood, Osborn received command of a small steamer, hms Dwarf, in which he patrolled the coast of Ireland during the insurrection of 1848. He was warmly thanked for his services by local authorities in Ireland and by his own commander-in-chief, and in 1849 he was reported to the Admiralty for gallantry “beyond all praise in remaining by his vessel, the Dwarf, in a sinking state in tempestuous weather.”

He returned to England in 1849 to find anxiety about Sir John Franklin*’s missing expedition reaching its climax after the failure of Sir James Clark Ross* in 1848–49. Osborn immediately joined the campaign in favour of a further expedition and volunteered to serve. The Admiralty decided to send out four ships under Captain Horatio Thomas Austin*, and Osborn received command of the 430-ton steamer hms Pioneer.

The expedition sailed in spring 1850; in the summer its members helped to locate and search the site of Franklin’s first winter quarters at Beechey Island; in September the ships were beset and forced to winter off Griffith Island in Barrow Strait. Close at hand were two other expeditions, one commanded by Sir John Ross*, the other by the veteran arctic whaling master William Penny*, who soon became one of Osborn’s closest friends. In spring 1851, Osborn led a sledge party south-westward to the western extreme of Prince of Wales Island. This 500-mile journey revealed no undiscovered coasts and other parties covered much greater distances. By far the most important of Osborn’s contributions to the expedition were his untiring cheerfulness, and his skilful handling of Pioneer, which proved the superiority of steam over sail in ice navigation. He wrote a popular narrative of the expedition, Stray leaves from an Arctic journal . . . , in which his jovial good humour is everywhere present. Yet the expedition was not altogether a happy experience for Osborn. He often disagreed with Austin, and, when Austin quarrelled with Penny, Osborn made little effort to conceal his much greater respect for the latter. When the expedition returned to England in autumn 1851, Osborn was the only officer whom Austin did not recommend for promotion. A number of his friends, including Penny, wrote to the Admiralty to protest, and Lady Franklin (Jane Griffin), was reported to be upset. Osborn himself remained unmoved, and received the news with a defiant forbearance that was typical: “I am young yet and have room & time enough to win a Post-Captain’s commission in spite of Captain Austin or any other Liar in buttons.” While the argument continued, Osborn was married, on 8 Jan. 1852, to Helen Harriet Gordon Hinxman.

Meanwhile, the Admiralty decided to send back Austin’s four ships with one added vessel, hms North Star, and they again gave Osborn command of Pioneer. Charge of the whole squadron went to Sir Edward Belcher.

On arrival in Barrow Strait in summer 1852 the ships separated. Captain Henry Kellett took two ships to Melville Island, North Star remained as base ship at Beechey Island, and Belcher and Osborn sailed Assistance and Pioneer up Wellington Channel to Northumberland Sound, northwest Devon Island, where they wintered. In spring 1853 Osborn sledged with an officer of Assistance, George Henry Richards*, along the north shore; of Bathurst Island and the northeast coast of Melville Island, both previously unexplored. He; then parted from Richards and, returning, explored the east coast of Bathurst Island. This journey lasted from 10 April to 15 July and covered more than 900 miles. During July and August the two ships sailed southward, but they were forced by ice to winter again in Wellington Channel. In September 1853 news reached Osborn from the supply vessel hms Phoenix of his promotion to commander on 30 Oct. 1852. Phoenix also brought out Osborn’s brother Noel, who spent the: winter as mate on board North Star. In 1854, to Osborn’s disgust, Belcher ordered all of his ships except North Star to be abandoned, and the men returned to England in her and in the supply vessels Phoenix and Talbot.

This voyage was undoubtedly the most depressing of Osborn’s career. Many of Belcher’s officers suffered under his humiliating and dictatorial treatment, but none more than Osborn. In 1853 he complained to Belcher of ill treatment and proposed to refer one difference between them to the Admiralty. From that moment, all the weight of Belcher’s wrath fell on Osborn. Richards kept a private journal through 1853–54, which records little else but Belcher’s “abuse & insult” and his “malignant hatred” of Osborn. Richards applauded Osborn for “the admirable way he has borne everything,” but there is no doubt that the latter’s good humour was sorely tested.

After the expedition, Osborn spent a short time in charge of the Norfolk coast guard while he recovered his health. He also began editing Robert McClure’s journal of his Franklin searching expedition on hms Investigator, which was published in 1856 as The discovery of the north-west passage . . . . Early in 1855 he was sent in command of hms Vesuvius to the Crimean War, where he was promoted captain on 18 Aug. 1855, decorated with the Order of the Bath, awarded the Turkish Medjidie, and made an officer of the Légion d’honneur by France.

The triumph of his return from the Crimea in 1856 was soon marred when his wife, by whom he had had two daughters, left him, or, as he defiantly expressed it, he “got clear of a bad wife by her absconding.” (There is no evidence that they were ever divorced.) Yet Osborn was certainly distressed. He was in poor health at the time, and for once he fell to despair: “My Naval career I feel is over,” he wrote to Penny. “I had an object and honourable ambition once – it’s gone now. I live merely for myself now, and it is little I want.” However, he was not yet 35 when he wrote these words, and his long career of naval achievements and unselfish public service had scarcely begun.

In 1857 he commanded hms Furious and escorted a fleet of gunboats to China, where Britain was again at war. When peace had been concluded, he was active in the development of European trade with China and Japan, and performed, in the words of Lord Elgin [James Bruce*], British ambassador to China, “a feat unparalleled in naval history” by sailing Furious 600 miles up the Yangtze (Ch’ang) River to prove its navigability for much smaller trading vessels. His health deteriorated during this service, and in 1859 he was invalided home. For three years he was obliged to supplement his income by editing some of his journals for publication, and by writing on naval matters, Chinese politics, and Arctic exploration for Blackwood’s Magazine. He also contributed papers to the Royal Geographical Society of which he had become a fellow in 1856. In 1861 he returned to the navy and subsequently began a period of varied activity. He commanded hms Donegal off the coast of Mexico. In 1863 he took a fleet of ships to Peking in an unsuccessful attempt to cooperate with the Chinese government in the suppression of piracy. In 1865–66 he was agent for the Great Indian Peninsular Railway Company in Bombay; in 1867–73 he was managing director of the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company which laid a submarine telegraph cable from Britain to India and Australia. He stood unsuccessfully for parliament in 1868, was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in June 1870, and won promotion to rear-admiral on 29 May 1873.

Polar exploration continued to occupy his mind in this period, however, and he led a successful campaign for the renewal of British Arctic interests. He presented a paper to the Royal Geographical Society in January 1865 arguing for exploration of the unknown region surrounding the North Pole by way of Smith Sound. He repeated his case many times and steadily gained support until, in August 1874, the government agreed to finance the venture, and the expedition of 1875–76 was born. For nine months Osborn, whose health prevented his making the trip, worked with Francis Leopold McClintock* and Richards on the Admiralty’s Arctic committee advising on preparations for the expedition. On 3 May 1875 he went to Portsmouth to visit George Strong Nares, commander of the expedition, and his crew. Three days later he died in London, shortly before the departure of the expedition that he, more than anybody, had made possible.

Sherard Osborn was one of the most talented naval officers of his day. Those who knew him paid tribute to his outstanding professional abilities, his courage and determination, his sound judgement, his warm-hearted enthusiasm, and his tireless good humour. He was admired by his fellow officers and by those who served under him. He was steadfast in his opinions, and seldom allowed diplomacy to prevent his expressing them – a feature of his character that brought him into conflict not only with Austin and Belcher, but also sometimes with his closest friends. Lady Franklin, for instance, was deeply upset because he consistently proclaimed Robert McClure – not her husband – as the discoverer of the northwest passage. In addition to Osborn’s accomplishments in the field of Arctic exploration, he was a capable administrator, a keen geographer, a prolific writer on many subjects, and an established authority on Chinese affairs; but most of all he was a highly gifted naval officer, a master of all aspects of seamanship.

SPRI, ms 116/57/1–10 (ten letters from Sherard Osborn to William Penny, 1850–56); ms 768 (private journal of George Henry Richards aboard H.M.S. Assistance, 17 Aug. 1853–28 May 1854). G.B., Adm., Further papers relative to the recent Arctic expeditions in search of Sir John Franklin and the crews of H.M.S. Erebus and Terror (London, 1855), 187–261. G.B., Parl., Command paper, 1852, [1436], L, 269–935, Additional papers relative to the Arctic expedition under the orders of Captain Austin and Mr. William Penny, 87–103. [McClure], Discovery of the northwest passage (Osborn). Sherard Osborn, Stray leaves from an Arctic journal; or, eighteen months in the polar regions, in search of Sir John Franklin’s expedition, in the years 1850–51 (London, 1852); “On the exploration of the north polar region,” Royal Geographical Society, Proceedings, IX (1865), 42–70; “On the exploration of the north polar region,” Royal Geographical Society, Proceedings, XII (1868), 92–112; “The routes to the north polar region,” Geographical Magazine (London), I (1874), 221–25. “Obituary,” Geographical Magazine (London), II (1875), 161–70. Times (London), 10, 14 May 1875.

Cite This Article

Clive A. Holland, “OSBORN, SHERARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/osborn_sherard_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/osborn_sherard_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Clive A. Holland |

| Title of Article: | OSBORN, SHERARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |