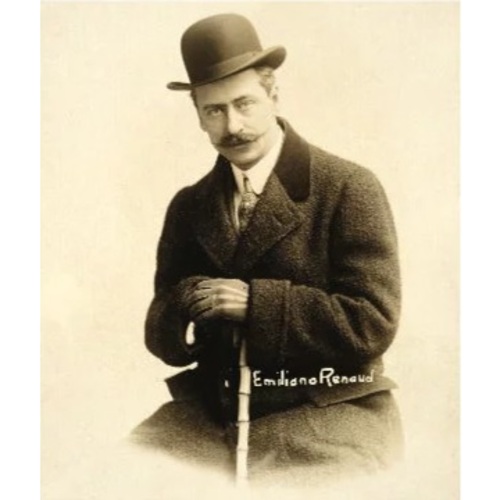

![Émiliano Renaud / Dupras et Colas . - [Vers 1910] Original title: Émiliano Renaud / Dupras et Colas . - [Vers 1910]](/bioimages/w600.12413.jpg)

Source: Link

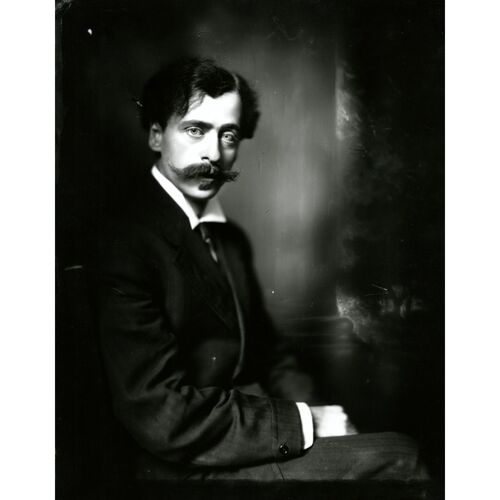

RENAUD, ÉMILIANO (baptized Anthelme-Marie-Renaud-Alexandre-Émiliano), pianist, organist, teacher, and composer; b. 26 June 1875 in Saint-Jean-de-Matha, Que., son of Zotique (Zothique) Renaud, a law student, and Dorothée La Salle; d. unmarried 3 Oct. 1932 in Montreal and was buried there two days later in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery.

Émiliano Renaud’s family settled in Montreal in 1875. Émiliano discovered the piano through his mother, and then studied for two years with Paul Letondal, one of the pioneers of professional musical life in Quebec. He pursued, but did not complete, classical studies at the Collège Sainte-Marie (1886–87 and 1890–91) and the Petit Séminaire de Montréal (1889–90). At the same time, he was the organist and accompanist for the student choir in those institutions.

In 1892 Renaud obtained his first job in Church Point, N.S., as a piano teacher and parish choir leader. A year later he returned to Montreal for health reasons. His meeting with Dominique Ducharme, a renowned piano teacher and student of Letondal, would date from this period. Ducharme professed great admiration for the pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski and introduced Renaud to his remarkable technique. In October 1896 Renaud left Montreal again, this time for Oswego, N.Y., where he was the church organist in the parish of St Mary. On 28 Jan. 1897, the day after his Montreal debut at the Young Men’s Christian Association, La Patrie was already calling him the Canadian Paderewski and predicting a promising future for him. That spring Renaud rounded out his studies in the city before departing for Vienna. Ducharme’s influence was not unconnected to Renaud’s decision to develop his talent in German-speaking countries rather than in Paris, the favourite destination of a number of artists from the province of Quebec. Renaud spent two years (1897–99) studying in Europe, first in Vienna and then in Berlin, under a disciple of Theodor Leschetizky, the former teacher of Paderewski.

On his return to Montreal in 1899 Renaud began a career as a concert artist: he appeared in recital as a soloist and as a chamber player with individual artists and prestigious groups such as the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal. He set new standards for the development of solo programs at a time when concerts were, for the most part, a collection of extracts played by several performers. Renaud introduced his own pieces as well as complete works by romantic composers such as Brahms, Chopin, Liszt, and Schumann, a repertoire that he played from memory and to which he would remain faithful throughout his entire life. The critics praised his technique and musicality, recognizing him as a true virtuoso. The day after his recital at Windsor Hall on 28 Sept. 1899, the music columnist for La Patrie paid this tribute: “He comes back to us, after going through the school that trained Paderewski and other great pianists, with considerable artistic knowledge. Those who have heard him are today unanimous in their appreciation of the exquisite style, the perfect technique, the intense feeling, the undeniable virtuosity of our young compatriot.”

The following year, on 20 April at Windsor Hall, Renaud gave the first performance of his concerto Concertstück with the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal. The next day a journalist from the Montreal Daily Star said of the evening: “He plays with virility and makes great bravoura effects.… In his composition, he has fulfilled the requirements of modern music thought, in that, he has had something to express of value and has expressed it with clearness and lucidity.”

On 22 Oct. 1901 Renaud, whose fame had already spread beyond Quebec’s borders, attracted notice when he made his debut at Toronto’s Massey Hall. His many successes on the country’s artistic scene and his collaboration with the faculty of the McGill Conservatorium of Music, founded in Montreal in 1904, prepared Renaud for his future career in the United States. For about five years (1907–11), he worked at the Indianapolis Conservatory of Music, first as a piano teacher and then as department head, temporarily setting aside his composing activities.

Around 1912, by which time he seems to have acquired a personal fortune, Renaud left the constraints of teaching to pursue a career as an independent artist, which was more in keeping with his temperament. He began composing again and moved to Boston, where he lived from 1912 to 1916 and where leading American publishers, such as the Oliver Ditson Company, undertook to publish his works. In 1912 he also accompanied Emma Calvé, a French star of the Metropolitan Opera in New York City, in a series of North American concerts, a tour that earned Renaud international status.

In 1917 the pianist decided to move to New York. He devoted himself to teaching – notably by founding his own conservatory – and to developing a method of learning piano by using records, without the need for an instructor. The Disk-phone piano method appeared in 1918, probably at the author’s expense. It was distributed again in 1920 under the name Renaud-phone piano method. The following year Renaud covered the cost of publishing it in French, under the original title. The method earned the approval of Paderewski and of the music critic of the New York Times, James Gibbons Huneker. This contribution to musical pedagogy furthered its democratization, a trend at that time.

Renaud returned to Quebec in 1921. He divided his professional life between giving concerts (some of which became the event of the artistic season), composing, collaborating as a performer and teacher at the radio station CKAC (for which he adapted his method in 30 lessons, a first in North America), and editing the monthly MusiCanada (1922–23). In 1924 he presented a series of three concerts at the prestigious Wigmore Hall in London, which would establish his reputation on British soil. When he died suddenly in Montreal on 3 Oct. 1932, the musical community lamented the loss of this highly esteemed musician.

As a composer, Renaud left a catalogue of some 50 works (a number of others are thought to have been lost), the majority for piano and voice, and a few pieces of chamber music, concert works, and two musical farces: Sandwich (1925) and its modified version, Djympko (1926). The English premiere of Djympko took place at Montreal’s Windsor Hall on 29 Nov. 1926. These compositions were not at all in keeping with the avant-garde or folkloric trends of Renaud’s time. He preferred to use the language of the 19th-century German composers.

At Windsor Hall on the evening of 17 Feb. 1930, several illustrious Canadian artists, including the tenor Rodolphe Plamondon and the violinist Émile Taranto, had joined with Renaud to perform his compositions. After Renaud’s death his works attracted little attention, apart from that of the famous contralto Sigrid Onégin, who would introduce into her repertoire the 1931 melody Le Pardon (which was dedicated to her), and that of the composer Eugène Lapierre, who would assemble the first catalogue of Renaud’s compositions in 1943. Many years would go by before they came to light again during a concert presented on 16 Oct. 1986 at the Université Laval as part of the International Year of Canadian Music.

Émiliano Renaud deserves an important place in Canada’s cultural landscape. Because of the diversity of his musical contributions, the quality of his programs, his remarkable performances, and his international reputation, he is considered to be the first virtuoso pianist from the province of Quebec.

The author wishes to thank Pierre Vachon, musicologist and director of civic impact and education at the Opéra de Montréal, for his preliminary research on Émiliano Renaud. The author also extends her gratitude to Monique Renaud, the artist’s niece, for the interview she granted on 17 Feb. 2011.

Further information concerning Renaud can be found in the author’s ma thesis, “Émiliano Renaud (1875–1932): premier pianiste-virtuose du Québec; interprète-pédagogue-compositeur” (univ. de Montréal, 2011).

Renaud’s works were published under different pseudonyms in the United States by American companies (the Oliver Ditson Company, White-Smith Music Publishing, New Music Publishing) and in Canada by Edmond Archambault*’s business, Nouveau Théâtre Musical, and the newspaper La Presse as well as in the magazine MusiCanada (Montréal). Some of his works also appeared in Canadian Musical Heritage Soc., The Canadian musical heritage (25v., Ottawa, 1983–99), 6 (Piano music II, 1986). Four of Renaud’s compositions were recorded on discs. Josephte Dufresne recorded his Prélude, fugue et choral. The manuscript of this work is not dated.

BANQ-CAM, CE605-S30, 1er juill. 1874, 27 juin 1875. LAC, R12142-0-8. Univ. de Montréal, Div. des arch., P365. Univ. Laval, Div. des arch., P269. Le Devoir, 18 févr. 1930, 20 oct. 1986. Gazette (Montreal), 4 Oct. 1932. Montreal Daily Star, 21 April 1900. Le Passe-Temps (Montréal), 17 mars 1900, 21 sept. 1918, octobre 1932. La Patrie, 28 janv. 1897, 3 oct. 1932. BCF. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). “Les Canadiens en Europe,” L’Art musical (Montréal), 3 (1898–99): 9. Dictionnaire biographique des musiciens canadiens (2e éd., Lachine [Montréal], 1935). E. [G.] Hesselberg, A review of music in Canada (New York and Toronto, [1912?]). L’heure canadienne, réalisation de Johanne Goyette (Radio-Canada broadcast, Montreal, 13 nov. 1988). Historica Canada, “The Canadian encyclopedia”: www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca (consulted 27 Jan. 2016). “Montréal,” L’Art musical, 1 (1896–97): 291. The musical red book of Montreal …, ed. B. K. Sandwell (Montreal, 1907). Franz Pazdírek, Universal-Handbuch der Musikliteratur/The universal handbook for musical literature (12v., Hilversum, Netherlands, 1967), 9. “Une invention canadienne: Huneker apprécie l’œuvre d’Émiliano Renaud,” Le Canada musical (Montréal), 3 (1919–20), no.2: 9. Vir, “Émiliano Renaud,” La Quinzaine musicale et artistique … ([Montréal]), 2 (1931–32): 41.

Cite This Article

Pascale-Andrée Bessette, “RENAUD, ÉMILIANO (baptized Anthelme-Marie-Renaud-Alexandre-Émiliano),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed July 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/renaud_emiliano_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/renaud_emiliano_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Pascale-Andrée Bessette |

| Title of Article: | RENAUD, ÉMILIANO (baptized Anthelme-Marie-Renaud-Alexandre-Émiliano) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | July 6, 2025 |