ROGERS, NORMAN McLEOD, soldier, university professor, author, civil servant, and politician; b. 25 July 1894 in Amherst, N.S., son of Henry Wyckoff Rogers and Grace Dean McLeod; grandson of William Henry Rogers*; m. 7 June 1924 Mary Frances Parker Keirstead in Wolfville, N.S., and they had two sons; d. 10 June 1940 near Newtonville, Ont., and was buried in Ottawa.

Norman Rogers was born to a well-educated Baptist, Conservative family. His mother, Grace, earned a ba from Dalhousie University and became a historian and author. She was best known for Stories of the land of Evangeline (Boston, 1891), a work of historical fiction that appeared in several editions; her novel Joan at halfway (New York, 1919) was favourably reviewed in the New York Times. In 1920 she became the first woman to run for a seat in the Nova Scotia legislature. Norman’s father, Wyc, was a lawyer and two-time mayor of Amherst, and his paternal grandfather, William Henry, invented fish ladders and served as federal inspector of fisheries for Nova Scotia.

Soldier and scholar

Norman Rogers completed his schooling in Amherst and worked as a mechanic at the Canadian Car and Foundry Company [see Nathaniel Curry] for a year before enrolling at Acadia University in Wolfville. He was active on student council, led the intercollegiate debating team, and befriended future cabinet colleague James Lorimer Ilsley*. In the winter of 1915, after the start of the First World War, Rogers enlisted as a private in the 6th Regiment (Canadian Mounted Rifles). The unit embarked for England in July and deployed to France three months later. After the regiment was broken up for reinforcements, Rogers was transferred to the 5th Battalion (Canadian Mounted Rifles), remaining attached to the 3rd Divisional Signal Company. He impressed his commanding officer, who observed: “Possesses general force of character. Fearless on duty.” Rogers was gassed at Sanctuary Wood, Belgium, during the battle of Mount Sorrel [see Malcom Smith Mercer*] in June 1916. Later that year he was invalided home to Canada, where he underwent prolonged medical treatment. He was discharged in 1918 as a lieutenant. His heart and lungs never fully recovered.

Poor health delayed Rogers from resuming his studies. Acadia gave him credit for his military service and awarded him a ba in 1919. He had won a Rhodes scholarship in 1918 but was unable to go to the University of Oxford until October 1919, when he entered University College. In three years he earned three bachelor’s degrees – arts (1921), letters (1921), and civil law (1922) – as well as a diploma in economics with distinction (1921). In the thesis for his second degree, “The settlement of labour disputes in Canada,” he praised federal Liberal leader William Lyon Mackenzie King* for his work as a labour conciliator. Professor Francis James Wylie, who became a mentor to Rogers, remembered that he must have set “a record for academic versatility and diligence at Oxford,” and “was, I think, the most industrious man I ever had to do with.”

University professor

Rogers returned home, telling Wylie that he was not tempted to stay abroad, as many Rhodes men were. His “one desire,” he wrote, “was to do my work in my own country, and in this respect I have never thought imperially. It must be Canada first and always, and then England.” In 1922 Acadia University appointed him Mark Curry professor and chair of history and political economy. He specialized in 17th- and 18th-century history and wrote on New France, particularly Acadia, working to correct the anti-French bias of earlier English Canadian historians. After reading law with his father in the summers, Rogers was called to the Nova Scotia bar in 1924, though he would never work as a lawyer.

Acadia University was growing, but Rogers did not intend to remain for long. In 1923 he had informed Wylie that he was “anxious” to migrate to “one of the larger Canadian Universities,” and the same year he wrote to King (who was now prime minister) seeking government employment. After Oscar Douglas Skelton* began to professionalize the Department of External Affairs in the mid 1920s, Rogers told King that he wanted to work there, writing, “this department appeals to me more strongly than any other.”

Rogers became politically active during the 1925 federal election campaign. He came out publicly for the Liberals, breaking with his family’s long connection to the Conservative Party. Hostile to British imperialism and concerned about relations between English and French Canada, Rogers felt more at home in the party of Mackenzie King. When the prime minister visited Acadia University during the lead-up to the election, he dined with the young professor on the campaign train and was impressed by him. Afterwards, Rogers wrote to King expressing dissatisfaction with his life as a history professor.

Private secretary to King

In 1926 King appointed Rogers co-secretary of the newly created royal commission on Maritime claims, chaired by British businessman Sir Andrew Rae Duncan. Before hearings could begin, King resigned from office after Governor General Lord Byng rejected his advice to call an election. The new prime minister, Arthur Meighen*, removed Rogers from the commission’s staff. When Meighen’s defeat in the House of Commons prompted an election, King offered Rogers the Liberal nomination in a Nova Scotia constituency, but he declined to run because Acadia University insisted that he would have to resign.

King returned to power after the election of 14 September, and the next year he hired Rogers as his private secretary. In this role he was responsible for speeches, correspondence, and briefs on various topics, including the 1927 dominion–provincial conference. According to some family stories, Rogers’s father had been incensed by his son’s conversion to Liberalism. Yet Wyc wrote lovingly to Norman that the appointment to King’s office gave him “great pride in all you have accomplished to date … for one so young & who had to overcome such handicaps.” King came to like, admire, and rely on his aide, but wrote in his diary on 14 Dec. 1927, “He is I fear very delicate.”

Progressive intellectual

In mid 1929, after illness forced Rogers to miss two months of work, he listened to medical advice and resigned from his job in Ottawa to teach political science at Queen’s University in Kingston. Yet he never completely left King’s side. Rogers worked full-time on the 1930 election campaign, and after the Liberals lost to Richard Bedford Bennett*’s Conservatives, he continued to assist King as an unofficial adviser, researcher, and speechwriter. He frequently visited Laurier House, King’s home in Ottawa, and the two men were so at ease with each other that they attended séances together. King was convinced that Rogers was a fellow spiritualist, but in all likelihood he was an intrigued skeptic. It did his ambitions no harm to have worked his way into King’s private life.

When history professor Frank Hawkins Underhill* approached Rogers in early 1932 about signing the manifesto of the League for Social Reconstruction (LSR), Rogers confessed to sympathizing with many of its objectives and to “becoming more radical rather than less so as the years pass.” But he held fast to the Liberal Party and its practical, step-by-step bent, and he told Underhill that the “human mind is not taken by assault but by persuasion.” His radicalism had perhaps been slowed by his Conservative roots, he admitted, “but I find my own pace accelerating.” Rogers encouraged the Liberals to sit on the progressive side of politics, and he kept ties with LSR members, including Underhill and McGill University law professor Francis Reginald Scott*.

Like O. D. Skelton and fellow Queen’s professor Adam Shortt, Rogers linked scholarship to the formulation of public policy. During his six years at the university, from 1929 to 1935, he engaged his students in serious debates about the people’s business. Rogers now wrote about contemporary problems, using his training as a historian to set them in a broad context. As part of his campaign for an activist federal government and constitutional reforms to limit the growth of provincial power, Rogers published influential academic articles on the meaning of Canadian federalism. He joined Underhill, Brian Brooke Claxton*, Stephen Butler Leacock*, and other prominent intellectuals in insisting that Canada was never meant to be, as Rogers put it, simply “a league of provinces.” At the same time, economic and social justice demanded a fair deal for every province. Acting as counsel for Nova Scotia before the royal commission of economic inquiry in 1934, he argued that Canada’s high tariffs had benefited Ontario and Quebec at the expense of the rest of the country, by robbing the Maritime provinces of their fragile industrial base and thereby reinforcing regional disparities.

Politician and biographer

In 1934 King asked Rogers to run in the next federal election in the Nova Scotia riding of Cumberland, the county where he had been born. He declined, explaining that he could not afford to give up his position at Queen’s and campaign for a seat he might not win. “If I were alone,” he wrote, “I would not hesitate to accept this risk. But I would not be justified in exposing my family to such a hazard in these times.” He reckoned that his savings would not last for more than six months. To live on a shoestring was “not compatible with self-respect and useful public service.” His political future was saved by the principal of Queen’s, William Hamilton Fyfe, who allowed Rogers to secure the Liberal nomination for Kingston City while carrying on with his teaching.

In the meantime, Rogers had reluctantly agreed to update John Lewis’s campaign biography Mackenzie King, the man: his achievements (Toronto, 1925). Rogers finished his work in early 1935, but King dismissed it as “inadequate and disappointing” and set about amending, redrafting, and adding to the entire text. Because Lewis, now a senator, did not wish to be listed as the author, Rogers allowed the revised Mackenzie King to come out under his name. It must have been difficult for the upright professor to take credit for a book mostly written by others, but years before, he had promised to do any “hard task” that King asked of him. The shabby book episode did nothing to diminish King’s wish to bring Rogers into parliament and make him minister of labour, the cabinet position that King had held under Sir Wilfrid Laurier* a quarter century before. In his diary entry for 9 Feb. 1935, King wrote of Rogers, “He is a noble and truly great man.”

Advertising himself as a soldier-scholar with “practical experience in government,” Rogers won the hitherto Conservative stronghold of Kingston City on 14 October. He taught his university classes on election day. Back in office with a majority government, King immediately told Rogers that he would be given the labour portfolio. The decision was enthusiastically supported by Ernest Lapointe*, who was soon to be the deputy prime minister in all but name.

Minister of Labour

In his new post Rogers confronted the ongoing Great Depression. Early successes included closing the controversial relief camps created by the Bennett government and organizing the 1935 dominion–provincial conference, at which Rogers achieved consensus that a national government body should oversee research on aid for the unemployed. King told his diary on 5 Aug. 1936 that Rogers might one day become Liberal leader and prime minister, “if he has the strength.”

King listened respectfully to Rogers’s ideas for combatting the depression and reforming Canadian society and the state, but many of those ideas went further than the Liberal leader was willing to travel. Cabinet colleagues also had a more limited view than Rogers of how far federal power ought to reach. In response to the decision made at the dominion–provincial conference, the National Employment Commission (NEC) was established in 1936. Rogers hoped it would allow ideas and reforms to germinate, but King saw it as a means to cut welfare grants to the provinces. When the NEC put forward Rogers-approved proposals for a federal takeover of unemployment assistance, King angrily denounced the labour minister inside and outside of the cabinet.

A similar drama played out when Rogers suggested fundamental changes in government practice. Twice he threatened to resign. According to civil servant John Whitney Pickersgill*, who closely observed the scene from King’s office, the Department of Labour remained the prime minister’s fiefdom, and he never quite trusted Rogers, despite his regard for him. In his diary entry for 12 Aug. 1938, King described a dream in which a container filled with acid “suddenly spurted out in the direction of Norman Rogers.”

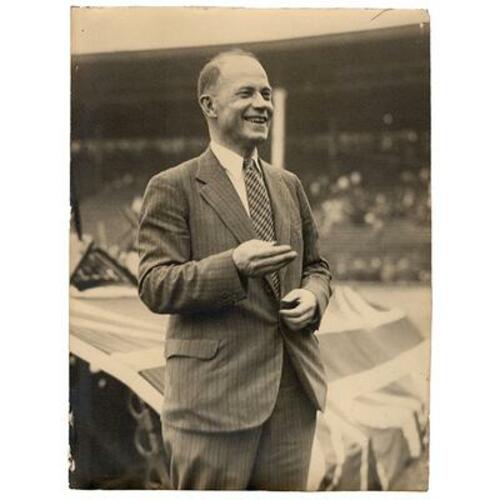

Contemporary descriptions of Rogers portray a man small in stature but large in intellect. Photographs show a relaxed professor, pipe in mouth. He worked hard but had a reputation for being easy-going and approachable, with a quiet charm and mischievous smile. His brown hair was thinning; his blue eyes were penetrating and full of youthful purpose. When debating in the House of Commons or wrangling with Mitchell Frederick Hepburn*, the renegade Liberal premier of Ontario, Rogers could be tough and combative. But as the Montreal Standard reported in a 21 May 1938 profile, labour was “the ‘suicide’ portfolio,” and the minister lacked the good health that King had once told him was the prerequisite of successful public service. In July 1939 Alexander Grant Dexter* of the Winnipeg Free Press had lunch with Rogers and found him defeated: “The unemployment problem seems to have beaten Norman. He regards it as insoluble unless the international situation improves.” Dexter wondered if Rogers wanted to run in the next election. The newsman had heard from his sources in the Department of External Affairs that Skelton was about to retire and Rogers might be appointed to succeed him as under-secretary. Skelton did not retire.

Minister of National Defence

On 19 Sept. 1939, nine days after Canada’s declaration of war on Germany, King transferred Rogers from labour to national defence as part of a major cabinet reorganization. James Layton Ralston*, the new minister of finance, could have had the national defence portfolio but recommended Rogers. King concurred. His protégé was steady and loyal, and seemed unlikely to become a captive of military interests. He and Rogers had agreed, as the crises mounted in Europe in the late 1930s, that Canadians had a duty to stand beside Great Britain if it were threatened. Rogers provided the competence that his predecessor, Ian Alistair Mackenzie*, had lacked. Commenting on Rogers’s cabinet debut as defence minister, King wrote, “We got the first intelligent and clear-cut statement from the Minister of the Department we have had in a year past.”

Rogers struggled with severe fatigue, and rumours spread that he would step down and be replaced by Ralston. The Conservatives launched outrageous personal attacks against him: Ontario leader George Alexander Drew* called him a “little dyspeptic son of Mars.” Rogers gathered up the “regrettable words” that had been thrown at him and used them in his campaign literature for the general election held on 26 March 1940. In a newspaper advertisement, the “outstanding Canadian gentleman” asked, “Why resort to personal abuse?” He was readily re-elected to his Kingston seat.

In April Rogers undertook a mission to the United Kingdom. During the trip he crossed the English Channel to confer with French leaders and visit military installations and the Vimy Memorial. In London he met with the beleaguered prime minister, Arthur Neville Chamberlain, and the determined first lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, who told him that “‘death’ was the only solution for the Nazi regime – no half-hearted measures had the slightest hope of success.” Rogers was critical of some of the British officials he encountered, and of the United Kingdom’s preparations for mechanized warfare. He left for home on 9 May. The next morning Germany invaded Belgium and the Netherlands, despite what Rogers had been told British intelligence was predicting. Churchill became prime minister that day.

On 10 June 1940, having been defence minister for only nine months, Norman Rogers died when the Royal Canadian Air Force Lockheed Hudson bomber carrying him to Toronto to deliver a speech crashed into the woods near Newtonville, in southern Ontario. He was 45 years of age. After the news reached Ottawa, King told a shocked House of Commons that before leaving Rogers had asked him if he should cancel the trip. When the prime minister advised against it, Rogers responded, “Very well, I will carry on.” The story fit with King’s belief that Rogers was the most selfless public servant he had ever known. It was a selflessness that King never failed to exploit.

The main archival sources for this biography are the Norman McLeod Rogers fonds at QUA, the diaries of William Lyon Mackenzie King (R10383-19-5) at LAC, and the Rhodes scholarship file for Norman Rogers at the Rhodes Trust Arch. (Oxford, Eng.). The authors are indebted to the Rhodes Trust for permission to use the Rogers material. William Archibald Mackintosh* wrote a short appreciation of Rogers’s life titled “Norman McLeod Rogers, 1894–1940,” Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science (Toronto), 6 (1940): 476–78. Information about the Rogers family is found in G. H. Rogers, Kindred spirits: a New World history of the families of Henry Wyckoff Rogers & Grace Dean McLeod (Renfrew, Ont., 2005). Of interest as well is Barry Cahill’s short biography, The life and death of Norman McLeod Rogers (Newcastle on Tyne, Eng., 2022).

Rogers’s most important academic studies are “The compact theory of confederation,” Canadian Political Science Assoc., Papers and proc. of the annual meeting (Kingston, Ont.), 1931: 205–30; and “The genesis of provincial rights,” CHR, 14 (1933): 9–23. The story of the birthing of Rogers’s Mackenzie King (Toronto, 1935), rev. and extended ed. of a biog. sketch by John Lewis (Toronto, 1925), is told by Mark Moher, “The ‘biography’ in politics: Mackenzie King in 1935,” CHR, 55 (1974): 239–49. The third volume of R. MacG. Dawson and H. B. Neatby, William Lyon Mackenzie King: a political biography (3v., Toronto, 1958–76), titled The prism of unity, 1932–1939 and written by Neatby, illuminates the intense relationship between Rogers and King. Doug Owram, The government generation: Canadian intellectuals and the state, 1900–1945 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1986), and James Struthers, No fault of their own: unemployment and the Canadian welfare state, 1914–1941 (Toronto and Buffalo, 1983), discuss Rogers’s ideas and his tenure at the Dept. of Labour. C. P. Stacey, Arms, men and governments: the war policies of Canada, 1939–1945 (Ottawa, 1970) and J. L. Granatstein, Canada’s war: the politics of the Mackenzie King government, 1939–1945 (Toronto, 1975) comment on the period when Rogers served as minister of national defence.

Cite This Article

Stephen Azzi and Norman Hillmer, “ROGERS, NORMAN McLEOD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_norman_mcleod_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_norman_mcleod_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Stephen Azzi and Norman Hillmer |

| Title of Article: | ROGERS, NORMAN McLEOD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |