Source: Link

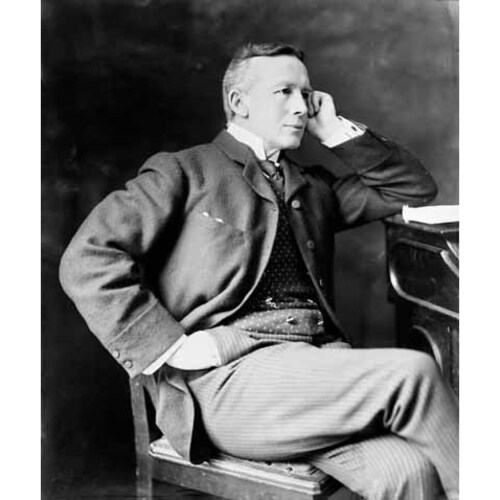

EWART, JOHN SKIRVING, lawyer and author; b. 11 Aug. 1849 in Toronto, son of Thomas Ewart and Catherine Seaton Skirving*; grandson of John Ewart* and nephew of Sir Oliver Mowat*; m. 25 Sept. 1873 Jessie Campbell in Toronto, and they had two sons and three daughters, one of whom died in childhood; d. 21 Feb. 1933 in Ottawa.

Beginnings

John Ewart was not yet two when he lost his father. Thomas Ewart died in Madeira, where he and his wife, Catherine, had gone in 1850 to combat the tuberculosis that soon killed him. Catherine came home to Toronto and her three children, who had been left with her sister, Jane Ewart (Mowat), and brother-in-law, Oliver, Thomas’s law partner. In 1854 Catherine, her son, John (known as Jack when he was a boy), and her two daughters moved to Scotland to live with relatives. They all returned in 1859 because, as Catherine explained, “Canada is decidedly my home and make no mistake.”

Jack Ewart was a child of the Toronto establishment. His grandfather John was a civic-minded architect, his father a budding Reform politician and ally of George Brown*, his mother a stalwart of Presbyterian Church philanthropy, and his uncle Oliver a supremely successful lawyer and politician. Jack rebelled. At Upper Canada College, where his father had been head boy, he was an indifferent student and inveterate prankster. He sold his books to buy a lacrosse stick, carved a wooden key to gain entry into the college’s private rooms, and tormented the teachers of a regimented educational system that he found “galling.” When he was 15, the college pronounced him “incorrigible” and expelled him.

Jack’s antics hid a fine mind. He needed inspiration, which was supplied by James Michie, a local merchant who shared his sophisticated library with Ewart. The lesson he took from his reading, much of it in religious and philosophical texts, was that he wanted a life of learning and self-improvement. He gave serious consideration to becoming a Presbyterian minister but opted for his father’s and uncle’s profession. He hired lawyer William Mulock* as a Latin tutor to ready himself for the entrance examinations at Osgoode Hall law school. The family’s connections did not hurt. Ewart’s successful Osgoode application was sponsored by future chief justice of Canada Samuel Henry Strong*. Ewart was called to the Ontario bar in 1871. It is possible that he worked in the law offices of Samuel Hume Blake* while a student and those of John Alexander Macdonald* in Kingston after graduation.

The law and politics

Upon joining Oliver Mowat’s law firm, Ewart demonstrated an aptitude for detail and order. He published an index of statutes in 1872 and a Manual of costs in 1874; both were reprinted in successive editions. He taught property law at Osgoode Hall and helped establish the Osgoode Literary and Legal Society. In September 1873 he married Jessie Campbell of Toronto. He had first proposed to her three years earlier, when she was 14, in a Valentine’s Day poem: “He’s bashful – he feels it – and trembles,” read the first line. A son was born in 1875, followed by another and three daughters, one of whom died at the age of four. There were regular family trips to Muskoka, and Ewart was one of the first 12 members of the Toronto Lacrosse Club, winners of the national championship in 1876. He moved away from Presbyterianism, eventually settling on more informal Anglican services.

Ewart’s intense schedule sometimes overwhelmed him and he suffered a bout of depression in 1880. Tuberculosis threatened, and he moved the next year to the drier climate of Winnipeg, where he practised law in partnership with James Fisher, a Manitoba mla, continued his ambitious publishing of legal texts, and established the Manitoba Law Journal. For a short time Ewart edged close to Winnipeg’s Liberals, perhaps in part because of his association with editor and politician William Fisher Luxton*, but he lacked the smooth edges of a good politician. His restless energy went instead to travel, the devouring of books on politics, economics, and history, and the delivering of glib talks on every imaginable subject, from Machiavelli to hypnotism to the archaeology of Jerusalem. He played tennis, curled, canoed, and competed in the city’s annual bicycle race until the age of 46.

In 1884 Ewart was made a qc. Although he derided the honour as an “invidious distinction” that offended his egalitarianism, he did not refuse it. He put his enhanced legal profile to use in support of two controversial Manitoba-centred causes. First, he was part of the team that appealed the 1885 treason conviction of Louis Riel* before the Court of Queen’s Bench of Manitoba. Speaking to a crowd of Riel partisans from the balcony of the St Boniface (Winnipeg) town hall after the appeal was denied, Ewart declared that he “never entered a case with greater heart.” Secondly, for more than five years he waged a battle in the courts and public arena to overturn Manitoba’s 1890 school bills [see D’Alton McCarthy*], which had ended publicly funded French Catholic education. He considered the 1896 Laurier–Greenway compromise [see Thomas Greenway*], which gave only minor concessions to the Catholic minority, a violation of the promises made to francophones at the time of Manitoba’s founding.

In 1904 Ewart decided to leave Winnipeg. Because he specialized in appeals before the Supreme Court of Canada and the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, a family residence in Ottawa made sense. His Manitoba real-estate investments having paid off handsomely, Ewart built a comfortable home at 400 Wilbrod Street in fashionable Sandy Hill and set up his practice at the Molsons Bank building downtown. He played golf inexpertly at the Royal Ottawa Golf Club and billiards with the precision and earnestness that he brought to everything he did. The high point of his legal advocacy came in 1910 with a four-day appearance on behalf of Canada at the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague. The court settled a long-standing North Atlantic fisheries dispute between the United States and Britain (including Canada and Newfoundland [see James Spearman Winter*]). Spurred on by his wife, he asked Sir Wilfrid Laurier* for a seat in the Senate. The prime minister put him off.

Anti-imperial crusader

At a time when most English Canadians had a strong sense of loyalty to Great Britain, Ewart wanted Canada to separate from the vast empire. Before coming to Ottawa, he had set out his aim in a 1904 address to the Winnipeg Canadian Club as its first president. The instruments of domestic autonomy had been painstakingly built up over generations, he reasoned, yet Britain and its enablers in Canada were keeping people in a state of dependency with, “naturally enough, the feelings of dependents.” He said that he understood why the men who dominated the empire from London would follow Britain’s interests, but he wanted Canadians to insist on the same privilege in their own affairs. Independence would force Canadians to take responsibility for themselves; self-reliance would promote “the sentiment of nationality” and tie a large and readily divided country together in a common destiny. In Ewart’s “Kingdom of Canada,” the historic British connection would be reduced, with two independent countries sharing a common king.

Ewart’s campaign for a sovereign Canada, which began with speeches and articles and a 1908 book, took a more concentrated form in his Kingdom papers, a pamphlet series that he launched in March 1911 and distributed gratis. His complaints about the habits and humiliations of colonial subordination were by now familiar, but they took on urgency because he feared that Canadians might become ensnared in a British war with Germany before extracting themselves from the empire. As of June 1912, there were 8,000 readers on Ewart’s mailing list and ten Kingdom papers ready to be indexed and sent out as a bound set. The Papers mirrored the man: they were highly organized, arrogantly confident, and out to win the argument at all costs.

When the First World War struck in 1914, Ewart put aside the Kingdom papers, now 20 in number, and dedicated himself to efforts to defeat the enemy and keep Canada united. Canada’s voluntary participation in the war would, he initially believed, move the country further along the path to true self-government. In late 1916 he parted from his autonomist ally, Canadian nationalist Henri Bourassa*, whose attacks on the government disrupted the domestic solidarity that Ewart believed was the prerequisite of a successful war effort. But he was soon doing some disrupting of his own. Ewart announced that he could not stand by while the British government used the war as a pretext for consolidating power in London and establishing institutions that robbed Canada of its autonomy. Kingdom paper no.21 was unleashed in August 1917, a broadside that vehemently accused Conservative prime minister Sir Robert Laird Borden of collaborating in an imperial plot against Canada. The paper ended with a demand, before it was too late, for an independent Canadian republic. At the same time, Ewart bitterly opposed Borden’s divisive conscription laws [see John Bain].

The war over, Ewart’s rhetoric lost its strident republicanism. He was an adviser to his Sandy Hill neighbour William Lyon Mackenzie King* as the Liberal prime minister eased Canada away from Britain in the early 1920s. King regarded Ewart as “very able & better informed than any one in Canada on foreign affairs,” but the prime minister insisted that a clean break from Britain was “too extreme.” The Evening Telegram described Ewart, now in his seventies, as the apparent model of wealthy and unthreatening Ottawa respectability, with “a near-statesman face, bounded on the north by nice grey hair and on the south by a conventional black coat and a grey vest.” But his radicalism was incurable. He remained, as Winnipeg Free Press editor John Wesley Dafoe* put it at the time, “primarily a controversialist” who “cares very little what the political consequences are.”

The obsessive writing continued until the end of Ewart’s life. In 1925 he published a two-volume study of the origins of the First World War. He concluded that national self-interest was “the exclusively dominating factor” in explaining why the Great Powers had tragically gone to war in 1914. Canada had to stay away from a Europe that would “fight and fight and fight again.” The war books took five years to finish, distracting Ewart from his multi-volume (and never-published) constitutional history of Canada, with its argument that his country had been its own creation from the American revolution onwards.

The last important writing project was Ewart’s Independence papers, begun in 1925 as a warning to Canadians that they were not yet a sovereign people and that a British war could too easily become a Canadian war again. The 27 pamphlets were self-published and sent out free of charge; the first four cost Ewart almost $2,300 to print and mail to 7,000 people. After gathering them in two hardcover volumes, he put a small price on the full set. Ewart had the habit of signing the books and adding the words “Canada is part of North America” to remind his readers that geography insulated them from “the hate-exchanging peoples of far-distant countries.” His final paper in the series claimed that, with the 1931 Statute of Westminster, Canada had emerged “from all semblance of political subordination to the United Kingdom.” Two years later John Ewart died of myocarditis.

Legacy

Ewart’s ideas had a constituency. His pamphleteering reached an audience in the thousands and a network of opinion-makers that included Dafoe, Bourassa, Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs Oscar Douglas Skelton*, lawyer and senator Raoul Dandurand*, Co-operative Commonwealth Federation leader James Shaver Woodsworth*, historian Frank Hawkins Underhill*, and professor-politician Norman McLeod Rogers. The core Ewart message, addressed to a country not yet fully formed, linked Canada’s potential to its fragility. He believed that Canadians would realize their shared destiny as an independent and self-respecting country only if they were tolerant and sufficiently mature enough to reconcile differences of language, religion, and region.

The author wishes to thank Theresa LeBane for her indispensable research assistance and dedicates this biography to D. L. Cole and D. M. L. Farr, the leading students of John Ewart’s life. Cole wrote “The better patriot: John S. Ewart and the Canadian north” (phd thesis, Univ. of Wash., Seattle, 1968) and “John S. Ewart and Canadian nationalism,” CHA, Hist. Papers, 4 (1969): 62–73. For years Farr collected Ewart documents, which he lent to Cole for his dissertation. Farr’s own assessment, “John S. Ewart,” is in Our living tradition: second and third series, ed. R. L. McDougall (Toronto, 1959), 185–214.

John Skirving Ewart is the author of Ewart’s index of the statutes … (Toronto, 1872); A manual of costs … (Toronto, 1874); and The roots and causes of the wars (1914–1918) (2v., New York, 1925). His writings on Canadian independence were collected in The kingdom of Canada, imperial federation, the colonial conferences, the Alaska boundary, and other essays (Toronto, 1908); The kingdom papers (2v., Ottawa and Toronto, 1912–[17]); and The independence papers (2v., Ottawa, [1930–32]).

The kingdom papers and The independence papers were compiled and printed in various forms during Ewart’s lifetime. They were available individually and, after a sufficient number were written, in bound volumes (although the unbound single numbers remained available for sale). Despite the stamp of McClelland, Goodchild & Stewart publishing house on the title page of the second volume, both volumes of The kingdom papers were privately bound. Most likely the publisher acted as printer for Ewart. A collection of Ewart’s articles, mainly published in the Canadian Nation (Ottawa) and the Statesman (Toronto), appeared in 1921 (Ottawa) under the title Independence papers. This publication should not be confused with Ewart’s collection of essays, initially produced since 1925 as individual pamphlets, and later issued in two volumes under the same title, with the first volume appearing in 1930 and the second two years later.

Ancestry.com, “Ontario, Canada, deaths and deaths overseas, 1869–1949,” John Skirving Ewart, 21 Feb. 1933: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/8946; “Ontario, Canada, marriages, 1826–1940,” John Skirving Ewart and Jessie Campbell, 25 Sept. 1873: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/7921 (both records consulted 9 April 2024). LAC, MG26-G (Sir Wilfrid Laurier fonds, political papers, general corr.), vol.617, J. S. Ewart to Laurier, 4 March 1910 (copy at heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c887, images 1038–39); vol.619, Laurier to J. S. Ewart, 15 March 1910 (copy at heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c888, image 467); MG26-J13 (Diaries of William Lyon Mackenzie King), 18 Jan. 1924 (copy at central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=diawlmking&id=17881&lang=eng). J. W. Dafoe, “The views and influence of John S. Ewart,” CHR, 14 (1933): 136–42. Norman Hillmer, “Growing up autonomous: Canada and Britain through the First World War and into the peace,” in Canada 1919: a country shaped by war, ed. Tim Cook and J. L. Granatstein (Vancouver and Toronto, 2020), 234–47. S. J. Potter, “Richard Jebb, John S. Ewart and the Round Table, 1898–1926,” English Hist. Rev. (Oxford, Eng.), 122 (2007): 105–32. Peter Price, “Fashioning a constitutional narrative: John S. Ewart and the development of a ‘Canadian constitution,’” CHR, 93 (2012): 359–81. R. St G. Stubbs, “John S. Ewart: a great Canadian,” Manitoba Law School Journal (Winnipeg), 1 (1962–65): 3–22. F. H. Underhill, “The political ideas of John S. Ewart,” CHA, Report of the Annual Meeting (Toronto), 12 (1933): 23–32.

Cite This Article

Norman Hillmer, “EWART, JOHN SKIRVING,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ewart_john_skirving_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ewart_john_skirving_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Norman Hillmer |

| Title of Article: | EWART, JOHN SKIRVING |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | February 19, 2026 |