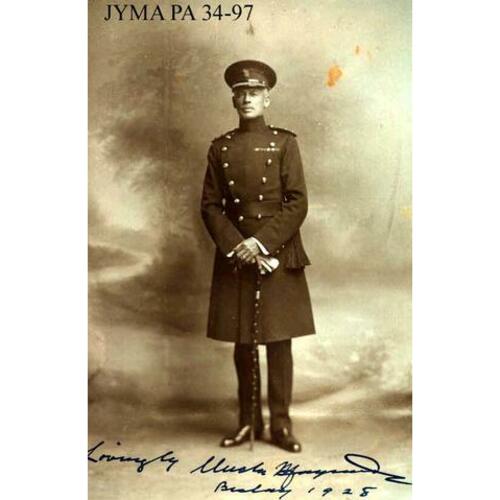

![Colonel Maynard Rogers in uniform [ca. 1928]. Image courtesy of Jasper-Yellowhead Museum and Archives (PA 34-97). Original title: Colonel Maynard Rogers in uniform [ca. 1928]. Image courtesy of Jasper-Yellowhead Museum and Archives (PA 34-97).](/bioimages/w600.13516.jpg)

Source: Link

ROGERS, SAMUEL MAYNARD, businessman, militia and army officer, bookkeeper, undertaker, and civil servant; b. 14 April 1862 in Plymouth, England, one of the three children of Samuel Rogers and Elizabeth Maynard; m. first 30 Nov. 1886 Annie Elizabeth Woodburn (d. 1 Dec. 1927) in Ottawa, and they adopted her niece; m. secondly 3 Dec. 1930 Mary Baldwin, former wife of John Baptiste Breuer, in the parish of St Marylebone, London, England; they had no children; d. 30 July 1940 in Ottawa and was buried there in Beechwood Cemetery.

Maynard Rogers was a young child when his parents settled in Ottawa, where his father, originally a cabinetmaker, became a prosperous undertaker. After graduating from the Ottawa Collegiate Institute, Maynard started working in his family’s funeral-home business. In 1881 he commenced a long career in military service by joining the local militia unit, the 43rd (Ottawa and Carleton) Battalion of Rifles. Four years later he was one of two staff sergeants in the hastily formed Ottawa Sharpshooters, which saw action under William Dillon Otter* during the North-West Rebellion [see Louis Riel*]. On 6 May 1885 the Toronto Daily Mail erroneously reported that Rogers had been killed at Cut Knife Hill (Sask.) four days earlier; in fact, Private John Rogers had been slain in the battle.

After the rebellion ended, Rogers returned to Ottawa and resumed his career in the family firm, working first as a bookkeeper and then, by 1891, as an undertaker. He also steadily ascended the militia ranks: he was promoted second lieutenant on 5 March 1886 and captain on 4 Jan. 1889, and he was appointed adjutant on 13 December of that year. Rogers earned a reputation as a marksman and belonged to several rifle squads, including the Canadian team that won the 1889 Kolapore Cup in Wimbledon (London), England. In September 1891 the 43rd Battalion was called upon to suppress the lumber workers’ strike in the Chaudière area, but the labourers were peaceful, and the unit was quickly sent home. Seven years later, on 22 June 1898, Rogers attained the rank of major.

When war broke out between Great Britain and the two Boer republics in South Africa in October 1899, Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* decided to raise troops for overseas service, and Rogers volunteered. On 18 October he was given command of D Company in the 2nd (Special Service) Battalion of the Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry. Between 18 and 27 Feb. 1900 the regiment fought at Paardeberg (Perdeberg), where it helped secure the first major British victory of the war. On the opening day of the battle, a bullet ricocheted off Rogers’s helmet and wounded a less fortunate soldier nearby. It was Rogers who reported on the heroism displayed by Richard Rowland Thompson* on the first and last days of the fighting. On 1 May, while participating in an attack on the village of Thaba Nchu, Rogers earned praise for keeping cool and steadying his men when they were shelled by Boer artillery. He served as commandant of the Canadian Depot in Cape Town before being released from active duty on 31 December, and was later awarded the Queen’s South Africa Medal, with four clasps: Paardeberg, Cape Colony, Driefontein, and Johannesburg.

Rogers returned to the family business in Ottawa, where he contributed to the community as a city alderman, a public-school trustee, president of the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Club and the Ottawa Hockey Club [see Ernest Harvey Pulford], and master of one of the local masonic lodges. He remained active in the 43rd Battalion, serving as second in command to Arthur Percy Sherwood, and he led it on parade on 11 Oct. 1901 at a royal review in Toronto before the visiting Duke of Cornwall, in whose honour the unit was renamed the 43rd Regiment (Duke of Cornwall’s Own Rifles). Rogers was promoted lieutenant-colonel on 8 April 1904, took over the regiment from Sherwood, and led it until 17 Feb. 1910. Less than two months later, on 9 April, he was made commanding officer of the 8th Infantry Brigade, a post he held for three years.

Rogers, who enjoyed rifle shooting, hunting, and fishing, was likely very pleased when the Conservative government of Robert Laird Borden appointed him superintendent of Alberta’s Jasper Forest Park (it would become Jasper National Park in 1930). Rogers arrived in March 1913 and quickly made an imprint by deciding on the uniform use of what he called the “rustic style of architecture” within the park. Its main administrative building, designed by Edmonton architect Alfred Merigon Calderon and built between 1913 and 1914 (it would be made a national historic site in 1992), doubled for some years as the superintendent’s residence. James Bernard Harkin*, commissioner of the dominion parks branch of the Department of the Interior, was impressed with Rogers, observing that he had “proved equal to the task of transforming a wilderness … into a park,” and noting that “even in one year he accomplished striking results.”

When World War I began in August 1914, Rogers promptly enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force at Valcartier, Que. His attestation paper indicates that he was 5 feet 9½ inches tall and had blue eyes, a fair complexion, a bald head, and two tattoos: a maple leaf, and the words “Canada South Africa 1899–1900.” Though Rogers was now 52 years of age, the doctor who conducted his physical examination commented that he looked much younger. On 27 August Rogers was named commanding officer of the 9th Infantry Battalion, a unit formed largely from Albertan recruits, which sailed for Great Britain a month later. He did not see combat during the war but filled a number of billets with various training brigades and the Canadian Training Division. He also served as a general staff officer before returning home in May 1916. By this time Rogers was a temporary full colonel, but he lacked a permanent post until 7 May 1918, when he became camp commandant at Valcartier, responsible for overseeing that summer’s training session. The armistice led to his discharge from the CEF, with the rank of lieutenant-colonel, on 15 Nov. 1918; he would retire from the militia six years later.

In late 1918 Rogers resumed his duties as superintendent of Jasper. He worked with Sir Henry Worth Thornton, president of the Canadian National Railways, to draw tourists to the park, and a golf course, bungalows, cottages, and Jasper Park Lodge, a luxurious resort with access to a railway line, were constructed for this purpose. In the words of scholar Ian S. MacLaren, the two men “oversaw the development of the resort into what for many park visitors stands for the park itself.” At the same time, Rogers sought to preserve Jasper’s natural environment by opposing coal mining in the park, supporting wildlife conservation, and pioneering the use of aerial photography to assist with patrolling and fire prevention. Harkin appreciated the military discipline and devotion to duty that Rogers brought to the job, but some of his habits were irksome to locals. He knocked on doors before dawn to admonish people who left their garbage-can lids unsecured, for example, and historian E. J. Hart notes, “he also came down hard on neighbourhood cats, shooting any that deigned to come near the chicken coop he proudly kept near his office.”

In April 1927 Rogers was transferred to the headquarters of the dominion parks branch in Ottawa to perform, according to the Ottawa Evening Citizen, unspecified “duties for which he has peculiar qualifications.” This move may have been a consequence of his wife Annie’s struggle with cancer, which took her life on 1 December. Over the next few years Rogers appears to have spent much of his time travelling. In 1928 he led the Canadian team at the Kolapore Cup marksmanship tournament in Bisley, Surrey, England, and in December 1930 he came home accompanied by his second wife, Mary Breuer (however, the marriage appears to have been short-lived).

Maynard Rogers served again as superintendent of Jasper from 1931 to 1934 before retiring to Ottawa, where he died on 30 July 1940 of cerebral thrombosis. His nephew George Harold Rogers, commanding officer of the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (the name of the old 43rd Regiment since 1933) and an undertaker himself, buried his uncle in the family plot in the city’s Beechwood Cemetery.

The Samuel Maynard Rogers fonds at LAC (MG55/30-No185) contains an album of photos taken by Rogers during the South African War.

LAC, RG150, Acc. 1992–93/166, box 8435-4. Ottawa Citizen, 19 April 1927, 30 July 1940. Can., Dept. of Militia and Defence, General orders (Ottawa, 1886–1925); Militia orders (Ottawa, 1899–1925). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Canadian who’s who, 1910. E. J. (Ted) Hart, J. B. Harkin: father of Canada’s national parks (Edmonton, 2010). I. S. MacLaren, “Cultured wilderness in Jasper National Park,” Journal of Canadian Studies (Peterborough, Ont.), 34 (1999–2000), no.3: 7–58. Parks Can., “Jasper National Park”: pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/ab/jasper (consulted 27 April 2017). K. W. Reynolds, Capital soldiers: the history of the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (Ottawa, 2011).

Cite This Article

Kenneth W. Reynolds, “ROGERS, SAMUEL MAYNARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_samuel_maynard_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_samuel_maynard_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Kenneth W. Reynolds |

| Title of Article: | ROGERS, SAMUEL MAYNARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2021 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |