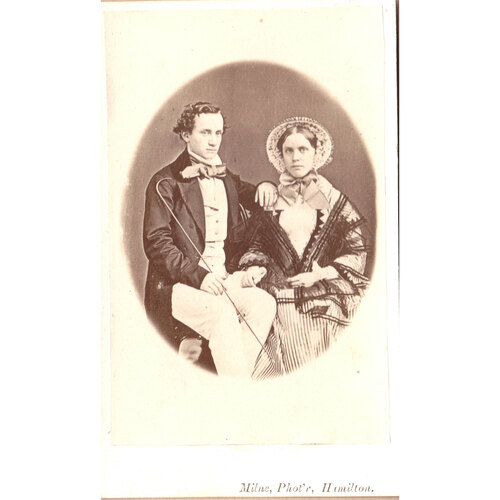

SANFORD, WILLIAM ELI, businessman, philanthropist, and politician; b. 16 Sept. 1834 in New York City, son of Eli Sanford, a carpenter, and Emeline Argall; m. first 25 April 1856 Emmeline Jackson, and they had one child; m. secondly 25 April 1866 Harriet Sophia Vaux in Ottawa, and they had two sons and two daughters; drowned 10 July 1899 in Lake Rosseau, Ont.

Shortly before his seventh birthday William Eli Sanford was orphaned. He was sent to Hamilton, Upper Canada, to live with his aunt Lydia Ann Sanford and her husband, Edward Jackson*, a wealthy tinsmith and prominent Methodist churchman. Upon his graduation from Central School, Sanford briefly attended a private school in Connecticut. At the age of 15 or 16 he clerked for a firm of booksellers and publishers in New York City before returning to Hamilton in 1856 to marry his cousin, the Jacksons’ only daughter. The couple subsequently moved to London; Sanford joined his uncle Edward Jackson and Murray Anderson in partnership in a local iron foundry known as Anderson, Sanford and Company. After 18 months of marriage, Emmeline died on 15 Nov. 1857, having given birth to a child who did not long survive her. It was a terrible blow for Sanford, who gave up his partnership and went back to Hamilton. There he soon became active in the wool clip trade.

Sanford, in association with two New York firms, is reputed to have captured a large share of this lucrative market in Essex, Kent, and Lambton counties. Yet, despite the profits, he remained in business for only about two years before moving into the manufacture of ready-made clothing. At the time most clothes were still made at home or by tailors. More efficient technology had only recently made its appearance, notably the treadle-operated sewing-machine [see Richard Mott Wanzer] and the band-knife. Increased productivity from these inventions made possible a market for ready-made clothing of good style, and Sanford and his partner Alexander McInnes seized the opportunity to pioneer the manufacture of men’s apparel in Canada. Sanford, McInnes and Company began operations in July 1861. Jackson contributed $10,000 and Alexander’s brother Donald put up a similar amount. The factory itself was little more than a warehouse for the cutting of fabrics and the storage of finished goods. The actual sewing was farmed out to highly skilled German tailors who distributed the pieces to several hundred women for assembly in their homes. These German immigrants came to Hamilton at the invitation of Albert Smith Vail, formerly a supervisor with a New York City clothing firm, who joined Sanford and McInnes as foreman in 1861. Of German descent and thoroughly fluent in the language, Vail was a popular figure among Hamilton’s large German-speaking population. His expert knowledge of tailoring made him a key member of the firm, and Sanford generously recognized Vail’s services.

By 1865 Sanford and McInnes were already looking to expand their premises and the following year they acquired an adjacent building for their growing trade. McInnes handled the office and warehouse; Sanford assumed responsibility for marketing, and his energy was a critical factor in the company’s success. He showed his samples throughout the Canadas as well as the Maritimes and by 1867 he had become the first Canadian clothing manufacturer to capture the Red River trade, with Alexander Begg as his agent. The firm’s margin of profit depended upon reorders, and Sanford succeeded in building a favourable reputation, which he maintained.

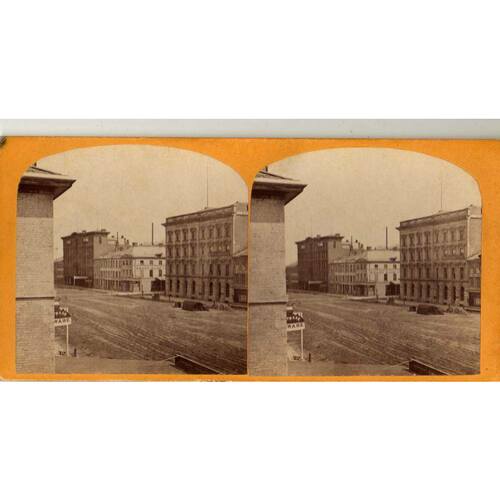

The firm’s spectacular expansion during the 1860s mirrored Hamilton’s impressive recovery from the depression of 1857 and its transformation into an industrial centre. The growth of Sanford and McInnes was helped by lack of competition from British industries and the United States because of the Civil War. From a small beginning – sales in the first year were $32,000 – Sanford and McInnes had become the largest clothing manufacturer in Hamilton by 1871 with sales of $350,000 and an inside workforce of 455. The next largest of the city’s 35 tailors or clothing manufacturers had sales of only $40,000 and employed a mere 15 workers. Indeed, the business was the fourth largest employer in Ontario and the largest in the clothing sector in 1871. By comparison, Toronto’s biggest clothing establishment produced $110,000 worth of goods and employed 124 workers.

When the partnership was dissolved late in 1871, Sanford brought Vail and Francis Price Bickley into the business, now styled Sanford, Vail and Bickley; they extended their agreement for three more years in December 1876. In 1879 Bickley retired and the remaining partners, along with William Henry Duffield, the firm’s bookkeeper, continued the business as Sanford, Vail and Company.

Throughout the 1870s the new firm prospered. Nevertheless, the Liberal government’s adherence to a policy of revenue tariffs, with the same amount of duty on ready-made clothing as on the cloth, put Sanford at a severe disadvantage in competition with the English manufacturers of shoddy. This was a substandard inexpensive cloth made especially for workers’ clothing. The shoddy clothes that Sanford was forced to import comprised about 30 per cent of his sales. In testimony before a House of Commons select committee, appointed in 1874 to investigate the problems of Canadian manufacturers, Sanford claimed: “We have an advantage over the English in the style and finish of the better class, but cannot compete with them in the very low-priced goods and make a living profit.” He urged the government, unsuccessfully, to raise the duty on imported clothing from 15 to 25 per cent to stimulate the production of domestic shoddy, a substandard, inexpensive cloth made especially for workers’ clothing. Thus protected, he argued, Canadian manufacturers would “wipe English shoddy goods out of this market.” And with the growing general demand for relatively fashionable ready-made clothing, Sanford claimed, his firm alone would gain “over $200,000 additional business.” A long-time member of the Reform (Liberal) party, Sanford had served as president of the local association. When the Liberals decided in 1876 to stand by existing tariffs, he, like George Elias Tuckett, a Hamilton manufacturer of tobacco, threw his support to the Conservatives and Sir John A. Macdonald’s evolving National Policy. Two years after the Conservatives returned to power in 1878, Sanford’s sales doubled, as did the number of his employees (from 1,000 to 2,000).

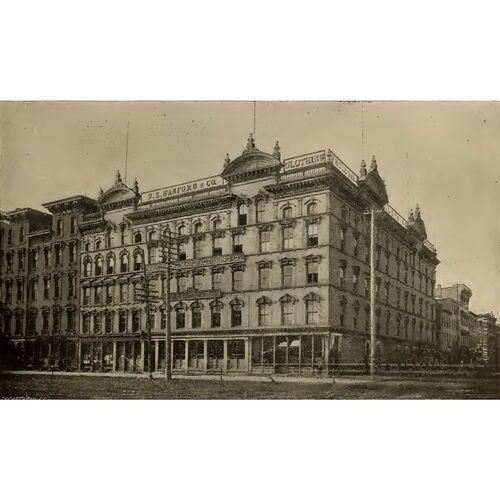

In 1881, under the protection of the National Policy, Sanford opened in Hamilton and Toronto the first of his chain of retail clothing outlets, called Oak Hall, a name which quickly became synonymous with clothes of good quality and moderate price. He opened stores in St Catharines (about 1888), London (about 1892), and Windsor (about 1895); during this period he also established three agencies: Winnipeg (1882), Toronto (1889), and Victoria (1890). By the early 1880s the original three-storey stone warehouse had given way to a four-storey building. The working part of it was equipped with the latest machines and labour-saving instruments. Each band-knife, for instance, was capable of cutting 100 pairs of pants per hour, 350 suits or 50 overcoats per day. The stockrooms were filled with a large assortment of men’s, boys’, and youths’ clothing of every grade and price, dress shirts, laced tweed and regatta shirts, an elegant stock of ladies’ mantles, and all classes of rubber goods and overalls. Sixteen salesmen canvassed the country, and during the busy season the firm shipped from $12,000 to $15,000 worth of goods daily to all parts of the dominion.

In an industry which encouraged outwork, the sewing-machine was as adaptable to cottage production as it was to factories, where workers were crowded into small, poorly lit shops. Sanford used both modes of production. The former provided low paid, largely female, and readily available workers incapable, for the most part, of organizing for their own protection. In his fight to stay ahead of the competition, Sanford followed prices set by the major clothing industries in Toronto and Montreal, but he was always ready to undercut his rivals. He sought neither to control nor to interfere with the low wages paid by his contractors, who passed on any reduction in price to their workers. His pursuit of a living profit was carried on in the face of his workers’ need for a living wage. In November 1896 the company announced a general wage reduction of ten per cent, which remained in effect for one year. Three months later Sanford attempted to impose a more drastic cut. He announced his intention to slash prices on two popular lines of overcoats by as much as 35 per cent. The coatmakers refused to accept the work and the city’s garment workers threatened a strike. Within two days Sanford consented to a smaller reduction.

The market for clothing opened up rapidly to Canadian manufacturers under the National Policy, but the Department of Militia and Defence continued to purchase uniforms from England. When Adolphe-Philippe Caron* became minister of militia in 1880 he determined to reverse this practice. He encouraged Sanford and a few others to visit the great military clothing factories in Pimlico, London, England. In 1883 the department issued the first all-Canadian clothing contracts except for the production of scarlet cloth, which was ordered from England until 1886. Sanford, who had purchased the necessary equipment after the Pimlico visit, tendered for an order of 5,000 greatcoats and appealed to Macdonald to assist him in obtaining it. After 1886 the department abandoned open competition for its clothing contracts in favour of a circular to the small coterie of wealthy manufacturers who had gone to Pimlico and subsequently made the investment necessary to produce cloth of the required standard. According to the same rationale of saving itself “trouble,” the department scrapped annual contracts for three-year ones.

After 1878 Sanford had become a generous contributor to, and a tireless worker for, the Conservative party. Macdonald called him to the Senate on 8 Feb. 1887 in recognition of his wealth and wide business contacts, and also of his leadership in the national Methodist church, whose strength the prime minister could not ignore. The decision was especially satisfying to the Methodists; their leading clergymen in Ontario had campaigned hard throughout the summer and fall of 1886 for the appointment. During the election of 1887 Sanford worked diligently in Hamilton, and, the Spectator commented, “perhaps no man in Hamilton worked more effectively.” One of the new senator’s first political appointments was to the board of directors of the Empire newspaper in Toronto, which the Conservatives had established in 1887. Like all partisan newspapers, it depended on contributions from party supporters. Sanford not only called upon his friends and associates but, in February 1888, initiated a fund-raising campaign among his customers. The response to the various appeals was not satisfactory, however, and the paper’s financial woes persisted.

After his appointment to the Senate in 1887, Sanford took immediate steps to incorporate his firm as a joint-stock company. He had been the sole proprietor since 1884 when his partners had retired and had been accustomed to deal directly with the government. As a senator, subject to the Independence of Parliament act, Sanford could do so only as a shareholder in an incorporated company. To avoid criticism while waiting for his patent, he assigned his 1886 government contract to another. Although he ceased to be the real contractor, Sanford’s interest remained “exactly the same,” as a select committee on public accounts looking into patronage surrounding clothing contracts reported in 1889. Criticism of patronage continued on the floor of the House of Commons to the end of the century. Much of the opposition’s attack centred on Sanford’s violation of the spirit of the act. Liberal mp James Somerville charged him with evading the law. “Whether Mr. Sanford receives this money as W. E. Sanford, manufacturer of clothing . . . or as the W. E. Sanford Manufacturing Company . . . the money goes into W. E. Sanford’s pocket,” Somerville argued. He also alleged that Sanford’s contracts were simply a reward for his generous contributions to the Conservatives. The contracts, however, continued after the Liberals returned to power in 1896, an indication that quality rather than merely patronage was the key criterion. A more serious accusation was collusion. In 1891 Somerville suggested that Sanford and Bennett Rosamond* of Almonte had a secret agreement to “share in the plunder.” William Mulock*, another Liberal mp, repeated the accusation the following year. In 1896 the former Conservative minister of militia and defence, David Tisdale, seemingly confirmed these allegations and the new Liberal minister, Frederick William Borden*, reported that Sanford had cornered the markets for scarlet serge and cloth for greatcoats. Borden also reiterated the long-standing suspicion that Sanford and others had conspired to fix prices. Sanford telegraphed him an indignant denial and requested that the minister read it into the record. Borden did so with “very great pleasure” and thereafter never again expressed any doubts about Sanford’s probity. Borden did, however, resurrect the one-year contract, but the practice of inviting by private circular the same firms to tender for militia orders remained in place.

Sanford’s memberships on Senate committees such as banking and commerce (1887–99) and railways, telegraphs, and harbours (1887–93, 1895–99) reflected his interest in the development of the Canadian economy. As a member of John Christian Schultz’s select committee on the resources of the Mackenzie River basin (1888), Sanford looked forward enthusiastically to the benefits of large-scale immigration. The vastness of the northwest with its seemingly unlimited potential had seized his imagination the moment he first set foot in it nearly 30 years earlier. In 1884, as the senior member of the North Western Drainage Company, he had received 52,000 acres of land from John Norquay*’s government in Manitoba in payment for draining the Big Grass marsh and Westbourne bog, an undertaking that was not completed until three years later. Since Sanford did not expect to sell the land for many years, he set aside 25,000 acres for a cattle ranch. The remainder was held for future profit. Put up for sale in 1898, it was subsequently disposed of as part of his estate “at prices varying from three dollars to thirty dollars per acre, thus realizing,” as his Winnipeg manager and executor put it, “a very handsome profit.”

Sanford eased the demands of an extensive manufacturing enterprise and the pressures of politics, to say nothing of his participation in various Methodist organizations and philanthropic endeavours, by shrewd judgement in choosing able men such as Albert Vail to help manage his affairs. Robert Thomas Riley, a farmer from the Hamilton area, was another who proved indispensable. He was hired in 1881 to let sub-contracts for the projects of the North Western Drainage Company. Work did not begin until the summer of 1882 and the job proved so discouraging because of high water that the other directors sold out their interests to Sanford. Riley then moved to Winnipeg and took charge of Sanford’s real estate deals, his branch clothing business, and the drainage contracts. In 1886, the year before the completion of the draining, Sanford brought together several of his wealthy Hamilton friends and organized the Westbourne Cattle Company on the 25,000 acres of land he had reserved for that purpose. The ranch began in a modest way with 60 or 70 brood-mares and some 400 cows with calves but soon increased to 200 horses and 1,000 cattle. At his annual sale of horses, Sanford ordered a special train out of Winnipeg just to ensure a “large attendance.” During the dozen or so years that the ranch operated, Riley recorded sales of 667 horses. No similar record exists for cattle but in one year 250 head were shipped to Montreal for export. Sanford also farmed 500 acres of wheat, which yielded from 30 to 50 bushels per acre.

If immigration to the northwest was critical to the expansion of domestic markets and Sanford’s own financial growth, so too was the encouragement of international trade. For years he attempted to establish an export trade without success. In testimony before a select committee in 1874, he noted that American protectionist policy effectively excluded his products. Even if the Canadian government were to offer a full rebate on the duty he would be unable to secure a foothold in that market because the American garment industry was so well established. In 1894 Sanford was in Washington, unofficially keeping Sir John Sparrow David Thompson informed of the stormy progress of a “freer trade” bill through Congress. He was on friendly terms with many of his political counterparts and regularly joined them for dinner or conversation in the smoking rooms. Indeed, he was so much at home that they referred to him “as one of our Senators from the State of Canada.” Trade with Australia, however, was his foremost objective and in 1888 his trade representative reported enthusiastically on the Australian demand for “Canadian Halifax tweeds, and all-wool light weight tweeds in knobby, effective styles.” The problem was the lack of a regular shipping link to develop the trade. But in spite of this difficulty Sanford never abandoned his effort to break into that market, and as late as 1895 his agent was still “canvassing the trade of the Australian colonies.”

Sanford speculated heavily in real estate. He was not only one of the largest landowners in Manitoba but also held numerous dwellings and lots in Hamilton and elsewhere. Not all deals turned out profitably. In 1880 Sanford purchased 1,000 acres of prime marble lands in Barrie Township with the intention of forming a company to develop the property. His plans never materialized because the market was too small to support an economical operation and the type of marble quarried was unfashionable. Sanford was a promoter and managing director designate of the proposed Saskatchewan Colonization Railway Company, vice-president of the Hamilton Provident and Loan Company, and director of the Exchange Bank of Canada. He was president of the Hamilton Board of Trade in 1876–77 and served on the executive committee of the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association in 1887–88; he does not, however, appear to have played an active role in the association.

Throughout his activity in business and associations related to it, Sanford was well known for his philanthropy, his public spirit, and his many acts of charity. A pillar of the Centenary Methodist Church in Hamilton from 1868, he carried on a tradition established by his uncle, one of its founders and leading members. He served as steward, secretary of the trust board, and treasurer of several funds, and was one of the principal subscribers to the building fund. He was a lay delegate to every general conference after the union of Methodist bodies. A devoted member of Centenary’s music committee, Sanford could take credit for the fact that the musical part of the services was considered the best in the city. He contributed liberally to the missionary, educational, and other agencies of the Methodist Church. He also supported the British and Foreign Bible Society, serving as vice-president of the Hamilton branch for a number of years.

In 1873, Sanford, on a visit to Victoria, “suggested that some permanent form of work should be undertaken” on behalf of the large number of Chinese there outside the “civilizing” influence of the Christian church. The following year he pledged $500 towards the establishment of a Chinese mission and promised a like amount annually to sustain its work. The Sanford Mission School, which began with great expectations, folded quickly because of racial prejudice and had closed its doors by 1877 or 1878.

Again like his uncle, Sanford was generous in his support of education. He was one of the original directors of the Dundas Wesleyan Boys’ Institute, which was incorporated in March 1873. Five years later he joined the directors of the Wesleyan Female College (later the Wesleyan Ladies’ College), serving as vice-president (1881–88) and president (1890–97). He was also a director of the Hamilton Art School. Victoria College was close to his heart and he sat on the college board (later the board of regents) from 1876 until his death. During the bitter debate over the college’s affiliation with the University of Toronto, Sanford stood with the proposal’s opponents, believing that the college should be “independent of state aid and state influence.” He even offered the Methodist Conference $50,000 to try to secure this “much-coveted prize” for Hamilton.

Another major concern was the child immigration program. Sanford became acquainted with it when the Reverend Dr Thomas Bowman Stephenson arrived in Hamilton in 1872 to establish a branch there of the Children’s Home. The purpose of the Children’s Home was to act as a distributing centre for immigrant children to be adopted into Canadian families as farm labourers, manual labourers, artisans, or domestics – in short, to do work for which the local supply was less than equal to the demand. In return, the children would receive regular schooling and a fixed scale of wages. Sanford’s sympathy had a personal dimension. In a speech to the St Mary’s Orphan Asylum in 1893 he remarked: “When I see homeless little ones . . . I feel real sympathy for them, for in my days of childhood I knew nothing of a mother’s love and a father’s care.” Of the first party of 34 boys sent to the home in May 1872, two found employment in Sanford’s warehouse. As treasurer of the Canadian work, he was responsible for receiving and banking the children’s earnings. He also took a great interest in following up the home’s placements and acted decisively in cases where a charge was either mistreated or neglected. He considered the program a resounding success and had harsh words for its detractors. He believed that children were the “most desirable immigrants” because they had “no established habits” and “with Canadian training and Canadian life they very rapidly assimilate and become the most reliable class of people.” Sanford is, perhaps, best remembered for Elsinore, constructed in 1890, at a personal cost of $10,000, as a non-sectarian summer home for the sick and destitute children of Hamilton. Situated on Burlington Beach, it was designed after the style of summer resorts with large, open verandas and pleasant, airy rooms. About 1896 the original policy was revised and Elsinore became a convalescent home for adult poor. It remained, however, a gift, maintained at Sanford’s expense.

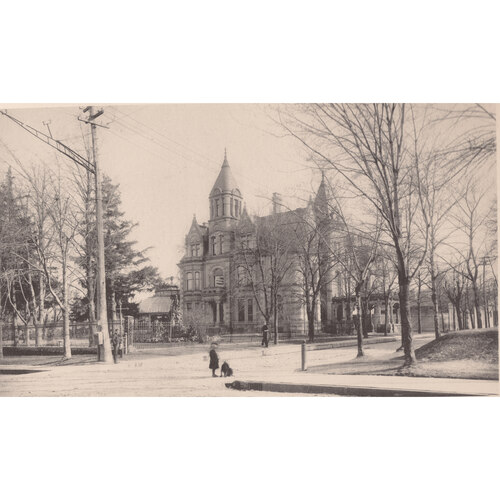

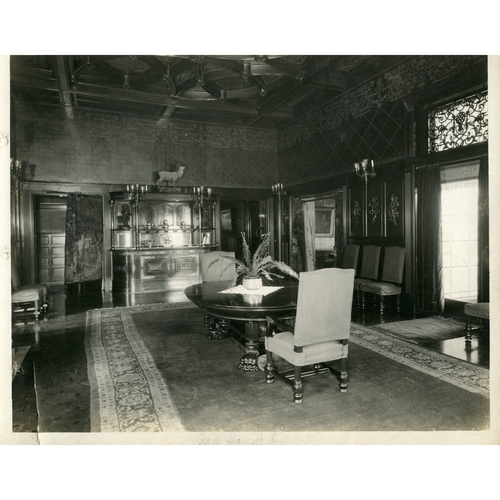

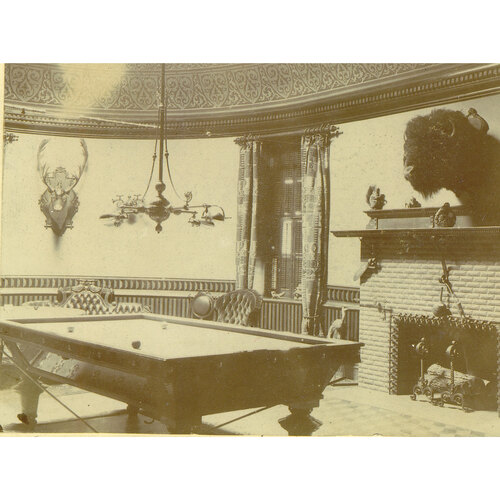

As the scale of his benevolence demonstrates, Sanford was a man of great wealth. He enjoyed its trappings. More than anything else, his home, which he had inherited from his aunt in 1875, came to symbolize his position within the community. Two years after moving into the house, he began the first of two major reconstruction projects which altered it beyond recognition. The second, finished in 1892, took two years to complete and made it one of the handsomest homes in Ontario, if not the country. A stately 56-room mansion, Wesanford (named after himself) was said to have cost about $250,000 for the second reconstruction alone. Its spacious grounds and conservatories covered half a city block; its richly decorated interior was filled with rare tropical plants and with paintings, statuary, and other art treasures, valued at $100,000, collected during numerous trips abroad. The house had the latest innovations: electric elevators, automatic gas-lighters, electrical orchestrinas, and a telephone system linking every room. The largest room, 50 feet by 28 feet, was described as “more like the banquetting hall of some old feudal castle than the entertaining room of a modern residence.” Such were his extravagant whims that the taps of a guestroom were inlaid with Royal Crown Derby. With its lavish furnishings, its pinnacled tower, colonnaded portico, and circular drive, Wesanford embodied Sanford’s status, as did his membership in the Hamilton Club, the Rideau Club in Ottawa, the Albany Club in Toronto, and the Royal Hamilton Yacht Club, of which he was commodore.

Sanford had always taken long holidays with his family in Europe and elsewhere. Nonetheless, business claimed most of his attention and his appointment to the Senate reduced the time spent with his family even further – four to six months a year at the “extreme limit.” Gradually, he and his second wife drifted apart for reasons which were only hinted at, and their separate lives became common knowledge. In 1894 Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks*] wrote in her journal: “We know full well that it is a notorious fact that when he arrives home Mrs Sanford goes away, & when she comes home, he goes away, & that there are reasons for this in his private life. Nothing has been openly brought before the Courts, & so we have asked him to dinner etc. & all that was his due as Senator but nothing more.” Sanford concocted the story of owning silver mines in Mexico which he visited yearly from 1897 until his death, a myth which was exposed by one of his executors, probably Mrs Sanford, after his death. He had pestered Lady Aberdeen and also Lady Thompson [Affleck*] for a knighthood but the former sniffed: “He is too hopelessly vulgar and indelicate for anything.”

Sanford’s death came suddenly at his summer home on Lake Rosseau. About to return from a morning’s fishing, he found his anchor wedged in rocks. Rather than exert himself, he cut it loose, tying his life preserver to it as a buoy. At that moment he was seized by a severe attack of rheumatism and capsized the boat. His young female companion had a life preserver but Sanford, unable to use his arms because of the attack, drowned. His entire estate, valued at over $1,000,000, went to his family with no provision for charity. The Hamilton Spectator explained, “He was of the opinion that the Ontario Government takes enough for that purpose by its succession duties.”

After a grand funeral, Sanford was interred in a mausoleum situated on a beautiful knoll overlooking Lake Ontario. Built at a cost of about $100,000, it is a scaled-down (30 feet by 18 feet) version of a Greek temple, with polished columns and richly carved capitals and bases. On the roof above the entrance stands a statue of hope with its right hand of grace raised heavenward and its left resting on the anchor of faith. Sanford sought not merely to perpetuate his name as a merchant prince, legislator, and Christian; he also hoped that his example, symbolized by this work of art, would prove, as the Kingston News expressed it, “instructive and inspiring to Canadian young men, as that of a businessman who, beginning with almost nothing, became wealthy and influential, while adhering strictly to Christian principles.”

The homily, however, is overdrawn. Sanford had wealthy origins and received his initial backing from his millionaire uncle. As he grew rich at the expense of his sweated labourers, he courted respectability, sought and received the prestige of a senatorship, and feathered his own nest. Wealth became an end in itself, something that must, as in the case of Wesanford, be seen to be appreciated and, only incidentally, the opportunity for fuller service. There is an irony here also. As the city’s largest employer, Sanford saw himself, not as an exploiter, but as a benefactor who provided hundreds of men and women and boys and girls with jobs and the opportunity to learn a trade so that they might become self-sufficient and contributing members of society. He never once paused to consider how precariously their lives hung in the balance of his pursuit of a living profit, nor how sumptuously he lived in contrast to their struggle for a meagre existence.

AO, RG 22, ser.205, no.4891; RG 53, ser.18, 8: f.28; RG 55, partnership records, Wentworth County, declarations, nos.114, 222, 655, 946–47; special declarations, no.12. Baker Library, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada, 25: 225 (mfm. at NA). Frontenac Land Registry Office (Kingston, Ont.), Abstract index to deeds, Barrie Township, concession 8, lot 27; concessions 9–10, lot 28; concession 10, lot 29. HPL, Scrapbooks, J. Tinsley, “Hamilton scrapbooks,” 3: 113. NA, MG 26, A; D (mfm. at AO); MG 28, I 230, 1; MG 30, C64, 32, file 4; RG 68, 118: 11. Univ. of Guelph, Ont., Dept. of Geography, Bloomfield databases, CANIND71, URBIND71, and RURIND71 (created from 1871 manuscript census schedules of Ontario industrial establishments).

Can., Dept. of Mines, Mines Branch, Report on the building and ornamental stones of Canada (5v., Ottawa, 1912–18), 1; House of Commons, Debates, 14 March 1879; 11 Aug. 1891; 12 April 1892; 25 Sept., 1 Oct. 1896; Journals, 1874, app.3; 1889, app.2b; Parl., Sessional papers, 1884, no.8; 1887, no.9; Royal commission on labour and capital, Report, Evidence – Ontario; Senate, Debates, 16 May 1888, 13 March 1889. Canada Gazette, 6 Sept. 1879, 12 June 1886, 4 June 1887. Information as to lands in Westbourne County, the property of the Hon. W. E. Sanford (Winnipeg, 1898; copy in AO, Pamphlet coll., 1898, no.45). [I. M. Marjoribanks Hamilton-Gordon, Marchioness of] Aberdeen, The Canadian journal of Lady Aberdeen, 1893–1898, ed. and intro. J. T. Saywell (Toronto, 1960). Methodist Church of Canada, Missionary Soc., Annual report (Toronto), 1874–84, continued as Methodist Church (Canada, Newfoundland, Bermuda), Missionary Soc., Annual report (Toronto), 1884–86. Ont., Royal commission on the mineral resources of Ontario and measures for their development, Report (Toronto, 1890).

Christian Guardian, 4 March 1874. Globe, 14 Jan. 1899. Hamilton Spectator, 12 April 1865; 7 July 1881; 11 Sept. 1886; 23 Feb., 15 March 1887; 1 July, 1 Nov. 1890; 4 April 1891; 8 June 1892; 15 Feb. 1893; 11 March, 17 May 1895; 3 Oct., 3 Nov. 1896; 30 Jan., 3 Feb., 8 March, 13 Oct., 3 Nov. 1897; 17 Jan. 1898; 13 Jan., 11–13, 21 July, 11 Nov. 1899. Monetary Times, 14 July 1899. Nor’Wester (Winnipeg), 14 Dec. 1867. Semi-Weekly Spectator (Hamilton, [Ont.]), 17 Nov. 1858. Canadian biog. dict. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.2. Hamilton and its industries . . . , comp. E. P. Morgan and F. L. Harvey (2nd ed., Hamilton, 1884). Hamilton Ladies’ College, Catalogue (Hamilton), 1877–96. Mercantile agency reference book, 1864–1900. Prominent men of Canada . . . , ed. G. M. Adam (Toronto, 1892). Victoria College, Calendar (Cobourg, Ont.), 1874–83, continued as Victoria Univ., Calendar (Cobourg; Toronto), 1884–1900.

William Bradfeld, The life of the Reverend Thomas Bowman Stephenson, founder of “The Children’s Home” and of the Wesley Deaconess Institute (London, 1913). The Centenary Church, the United Church of Canada, 24 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, 1868–1968 ([Hamilton, 1968]). The history of the town of Dundas, comp. T. R. Woodhouse (3v., [Dundas, Ont.], 1965–68), 3. Margaret Morton Fahrni and W. L. Morton, Third crossing; a history of the first quarter century of the town and district of Gladstone in the province of Manitoba (Winnipeg, 1946). S. S. Osterhout, Orientals in Canada: the story of the work of the United Church of Canada with Asiatics in Canada (Toronto, 1929). R. T. Riley, “Draining the marsh,” When the west was bourne: a history of Westbourne and district, 1860 to 1985 (Westbourne, Man., 1985). C. E. Sanford, Thomas Sanford, the emigrant to New England; ancestry, life and descendants, 1632–4 . . . (2v., Rutland, Vt., 1911). G. E. Evans, “Yachting on Lake Ontario,” Dominion Illustrated Monthly (Montreal), [2nd ser.], 1 (February 1892–January 1893): 370–83. Globe and Mail, 6 May 1938. Hamilton Spectator, 10 May 1938.

Bibliography for the revised version:

FamilySearch, “Canada, Ontario, county marriage registers, 1858–1869,” William Eli Sanford and Harriet Sophia Vaux, 25 April 1866: www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2CB-3XY5?cid=fs_copy (consulted 2 Feb. 2023). Find a Grave, “Memorial no.22092441”: www.findagrave.com (consulted 2 Feb. 2023).

Cite This Article

Peter Hanlon, “SANFORD, WILLIAM ELI,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 8, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sanford_william_eli_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sanford_william_eli_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter Hanlon |

| Title of Article: | SANFORD, WILLIAM ELI |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | February 8, 2026 |