Source: Link

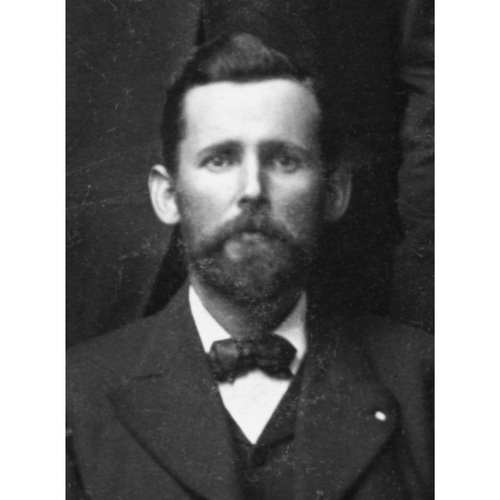

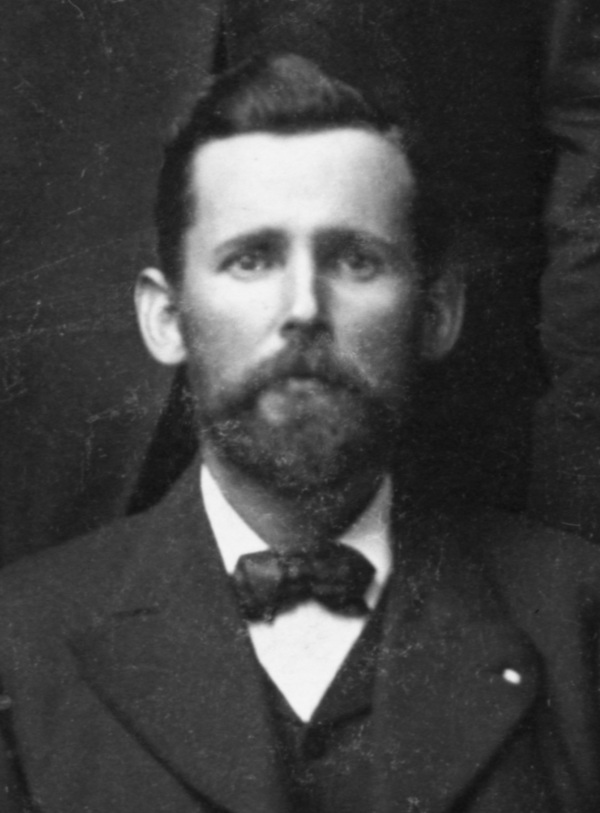

SHERMAN, FRANK HENRY, miner, labour organizer, and political activist; b. 10 May 1869 in Gloucestershire, England; m. 1891 Annie Beaven, and they had eight children; d. 11 Oct. 1909 in Fernie, B.C.

Early in his life Frank Sherman’s family moved from southwestern England to south Wales, and his formative years were spent in the Rhondda valley, the cosmopolitan centre of a burgeoning coal industry. He was apprenticed and worked in the mines there until the great strike of 1898, after which he came to feel that he was a marked man. Like others of his fellow workers, he chose to emigrate.

According to one history, the experience of the south Wales miners was “one of compromise as well as of defiance, with a string of defeats and precious few victories, with a culture in as much flux as the population was fluid.” In the Canadian coalfield that Sherman eventually adopted as his new home, a broadly similar situation obtained. Between 1897 and 1909 a number of mines would be developed in the Crow’s Nest Pass, a raw frontier region straddling the border between British Columbia and Alberta. The name of the Crow’s Nest coalfield became synonymous with the exploitation of foreign labour, harsh and dangerous working conditions, and savage industrial relations. Not surprisingly, collective action by the workers began early. Welsh miners were among those in the vanguard and, just as the South Wales Miners’ Federation had formed in 1898 in Britain under moderate, Methodist leadership, so in 1899 emerged the Gladstone Miners’ Union at Fernie, site of operations of the giant Crow’s Nest Pass Coal Company.

By 1902 Sherman was a checkweighman in the colliery at Morrissey, keeping watch on the company’s estimate of how much coal each miner extracted. Like many others in the coalfields, the Shermans were nearly always penniless. Such economic insecurity contributed to the radicalization of the Welsh diaspora in the 20th century. Their evangelical nonconformist tradition merged, at least to some extent, with the radical critique of industrial capitalism. Once a chapel preacher, Sherman would eventually join the Socialist Party of Canada, a doctrinaire Marxist organization established in 1904, although he never found a true home in that party.

In the early 1900s conditions in the Crow’s Nest coal industry led to the ebb of reformism among workers and the rise of a militant and socialistic unionism. First the Gladstone Miners’ Union affiliated itself for a brief time with the American-led Western Federation of Miners. Then in 1903, with Sherman as founding president, District 18 of the United Mine Workers of America was established. Between 1904 and 1906 union organizing spread eastwards into the coalfields around Lethbridge, Alta, and Sherman took a prominent part. In his view, however, union activity was not the only, or even the most important, means of improving the workers’ lot. He believed that the real solution was to gain control of the state through democratic political action. Hence in 1905 he ran as the United Mine Workers–Labour candidate for Pincher Creek in elections to the first Alberta legislature. His platform, opposing “the trusts” and “political graft” and supporting home industries and public utilities, would not have alarmed any progressive Liberal or Conservative. Although defeated, he received one-third of the ballots cast. In a by-election in Lethbridge the next year, he came within 80 votes of winning.

Meanwhile, in March 1906 the workers at Alberta’s largest mine, owned by Elliott Torrance Galt*’s Alberta Railway and Irrigation Company, went on strike, one of their demands being recognition as a local of District 18. In November they were still out and the residents of Saskatchewan, who depended heavily on the mine for their heat, anticipated a serious fuel shortage as winter closed in. The federal minister in charge of the Department of Labour, Rodolphe Lemieux*, sent his deputy minister, the young William Lyon Mackenzie King*, to mediate. The resulting settlement increased pay and established a grievance procedure, but it did not give formal recognition to the union.

As District 18 president, Sherman had none the less played an important role in the negotiations. His charismatic personality attracted King’s notice, and sources suggest that the Liberals did their best to draw him into their ranks. Sherman had no fonder ambition than to represent the miners politically, but he was unwilling to sacrifice his independence in the way that mp Ralph Smith* had done by joining the Liberal caucus. When Sherman contested the sprawling Calgary constituency in the dominion elections of 1908, he ran on the Socialist Party of Canada ticket. The Lethbridge Daily Herald, a Liberal newspaper, remarked that his “striking personality and intellect” were acknowledged by even his “bitterest enemies.”

While Sherman was pursuing the political option, he was also leading the extraordinarily arduous life of a full-time labour activist, at a time before the emergence of union bureaucracies. As head of a 6,000-member district, he was personally responsible for much of the bargaining. He had to deal with more than a score of employers, who were loosely organized into the Western Canada Coal Operators’ Association. From 1907 local and district negotiations followed the complex legalistic procedures laid down in the Industrial Disputes Investigation Act, which forbade strikes or lock-outs in coalmines until the dispute had gone before a board representing labour, management, and the public. Sherman had initially been sympathetic to this so-called Lemieux Act, but he quickly became convinced of its anti-labour bias. At the Winnipeg and Halifax conventions of the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada in 1907 and 1908 he attempted, without success, to rally the main body of Canadian trade unionism behind the miners’ campaign for repeal. Undaunted by the tepid response of the eastern-based craft unions, whose leaders he now denounced as “fossils,” he pledged to take the campaign “to the foot of the Throne.” (Eventually, in 1925, the act was struck down by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.)

At the same time as Sherman was fighting the Lemieux Act, relations between District 18 and the central office of the United Mine Workers of America in Indianapolis, Ind., were becoming increasingly strained. A fierce advocate of district autonomy and, generally speaking, a supporter of the impotent left wing of the international union, Sherman by 1909 was moving towards an open declaration of independence for District 18, which he saw as the first step in the creation of a separate and progressive Canadian federation of labour. This particular enthusiasm of Sherman’s owed something to the ideas of Honoré Joseph Jaxon [William Henry Jackson*], once secretary to Louis Riel* and now Sherman’s aide-de-camp and personal secretary.

Sherman’s isolation was dramatized during the Alberta coal strike of 1909, a little-known confrontation that marked the end of an era of compromise in industrial relations on the coalfields. A contract between District 18 and the operators’ association, signed under the auspices of the Department of Labour after a short strike in 1907, was due to expire on 31 March 1909. The coal trade was slack and Alberta mine owners faced particular difficulties because of their dependence on the Canadian Pacific Railway as a market. Hence the operators came to the table with demands for concessions. At first the bargaining committee for the union acceded to a number of the proposals, but Sherman, who had been absent because of serious illness, rose from his sickbed to denounce the terms. A separate and better peace was concluded with the British Columbia operators, but nearly all Alberta operators, encouraged by the CPR, stuck to their guns. On 1 April, in direct contravention of the Lemieux Act and the dictates of the international union, the bulk of the Alberta members went on strike. Without the political stimulus of coal shortages, the government was not prepared to intervene. King, who was about to become the minister of labour, begged off any role as mediator. “I would much prefer not adding to my troubles by being drawn into yours,” he wrote to Sherman on 28 April. Meanwhile, on 16 April Sherman was expelled from the Socialist Party of Canada for trafficking with Liberalism.

The strike dragged on for another three months before the Department of Labour used its “good offices” to secure an unsatisfactory compromise. This settlement only set the stage for a bitter and violent strike in 1911. Eventually the organized miners became convinced that no solution short of nationalization “under workers’ control” could resolve the difficulties of the district, and Sherman’s utterances on a variety of subjects would be cited in support of the radical program of the One Big Union in the era of World War I.

Sherman himself did not live to see the tumultuous events of that decade, for which he more than anyone else had paved the way. As the 1909 strike drew to a close, he tendered his resignation to the district executive, writing: “The past six years I have been in your service have been the most strenuous in my life. The many calls upon my services and the burdens that I have been expected to carry, together with excessive and constant travel have broken me down.” He was suffering from the terminal stages of Bright’s disease, a degeneration of the kidneys often associated with exposure to toxic materials and a commonplace affliction among underground miners. Despite efforts by some of the local unions to raise enough money for his treatment at an eastern clinic, he died in the Fernie hospital in October 1909. Ironically, in his last days the wicked Crow’s Nest Pass Coal Company had offered him the early-20th-century equivalent of retirement, an “outside” job, but the union funds promised for the support of his bereaved family never materialized.

A coalminer, trade unionist, and political activist, Frank Sherman was typical of the working-class leaders thrown up in western Canada by mass immigration and rapid economic growth at the turn of the 19th century. The Fernie District Ledger, which he had edited, paid tribute to him as one of those who “from sheer force of character and purpose, force themselves up from the ranks of the toilers, notwithstanding overwhelming obstacles, to grapple with the problems . . . of their class.” The permanent establishment of unionism in the Crow’s Nest Pass and Alberta coalfield was the chief accomplishment of his all-too-brief career. Annie, his eldest daughter, went on to become prominent in the Communist party of New Zealand and the Blackball Miners’ Union there. His son William was active as an organizer with the United Mine Workers of America and was murdered in the Pennsylvania coalfield in 1933.

[The author would like to thank members of the Sherman family living in Surrey, B.C., for their assistance in the preparation of this biography. a.s.]

Univ. of B.C. Library, Arch. and Special Coll. Div. (Vancouver), Sherman papers, esp. King to Sherman, 28 April 1909; Sherman to District Board, 17 June 1909. District Ledger (Fernie, B.C.), 16 Oct. 1909. Frank Paper (Frank, Alta), 15 Oct. 1909. Voice (Winnipeg), 16 April 1909. D. J. Bercuson, Fools and wise men: the rise and fall of the One Big Union (Toronto, 1978). W. J. C. Cherwinski, “Honoré J. Jaxon, agitator, disturber, producer of plans to make men think, and chronic objector . . . ,” CHR, 46 (1965): 122–33. Paul Craven, “An impartial umpire”: industrial relations and the Canadian state, 1900–1911 (Toronto, 1980). Alan Derickson, Workers’ health, workers’ democracy; the western miners’ struggle, 1891–1925 (Ithaca, N.Y., 1988), 54. Hywel Francis and David Smith, The Fed: a history of the south Wales miners in the twentieth century (London, 1980), 2. McCormack, Reformers, rebels, and revolutionaries. Len Richardson, “Class, community and conflict: the Blackball Miners’ Union, 1920–1931,” Provincial perspectives: essays in honour of W. J. Gardner, ed. Len Richardson and W. D. McIntyre (Christchurch, New Zealand, 1980), 107.

Cite This Article

Allen Seager, “SHERMAN, FRANK HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sherman_frank_henry_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sherman_frank_henry_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Allen Seager |

| Title of Article: | SHERMAN, FRANK HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | February 19, 2026 |