Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SIMON DE LONGPRÉ, MARIE-CATHERINE DE, dite de Saint-Augustin, nun of the Hôtel-Dieu of Quebec, daughter of Jacques Simon, Sieur de Longpré, and of Françoise Jourdan; b. 3 May 1632 at Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte (Lower Normandy); d. 8 May 1668 at Quebec.

A precocious child, Catherine grew up under the care of her grandmother and her maternal grandfather, M. de Launé-Jourdan, “a man of prayer and grand almoner, whose virtue has been appreciated by everyone.” At the age of three she showed herself to be imbued with a desire for the heroic and the absolute, and asked how she might in all things do God’s will. Her spiritual adviser, the Jesuit Father Malherbe, explained this to her in the presence of a pauper covered with sores. Catherine concluded from his illustration that it is easier to find God in humiliation and suffering than in prosperity. The tiny tot then began, “with unbelievable earnestness,” to wish for “many maladies.” An ear infection that degenerated into bone decay started to torment her. Catherine undertook to accept everything joyfully and she was cured, despite the treatments of the surgeons of the period, wretched quacks whom Molière rightly held up to ridicule. Without turning a hair, Father Paul Ragueneau describes one of these “operators” in the act of pouring red-hot ashes into the ears of Mlle de Longpré.

At the age of ten, “unaided by any visible person,” Catherine composed a “Donation” to the Blessed Virgin, a text worthy of an adult. Like her contemporaries in the first part of the 17th century, the little girl affirmed her yearning for epic deeds. And so her impetuosity burst forth in uncompromising formulas: “Remove from my heart every impurity, let me die now rather than allow my heart and soul to be soiled by the slightest blemish.”

Despite their predisposition to panegyrize, the hagiographers record a complete reversal of Catherine’s attitude. Was this a normal adolescent crisis, or an awareness of her deep and engaging femininity? Catherine realized that she was pretty, intelligent, and attractive, and made use of her charms to conquer those about her. To some extent she imitated the precious ladies of the Hôtel de Rambouillet; she sang love songs, and read novels, perhaps L’Astrée and Polexandre. In summarizing this brief period of exuberance, Catherine wrote: “I took pleasure then in being loved and in seeking friendship without wanting to appear to be doing so; on the contrary, I gave the appearance of much severity, in order to be considered an independent thinker.”

When she was twelve and a half, Catherine underwent a “bad shakeup”: she felt that God was calling her to the cloister, but she balked, because the world attracted her. “I tried,” she said, “to stifle it all by seeking diversions.” But ever pursued by her obsession with pleasing God, she became a Hospitaller of Bayeux on 7 October 1644, joining her elder sister there. Thinking herself “too young and too small” to make a final decision, she jauntily notified the authorities of the hospital that she was not coming to the noviciate with the express intention of staying there, “but merely to try it out and to see something of how the nuns live.” She was put to the test “twofold,” for fear that her vocation might have sprung from a desire for human esteem. Catherine remained firm, however, and openly challenged the mistress of novices: “Do what you like to me, you will not make me give up the nun’s habit and I will not leave here except to go to Canada.”

These prophetic words were not long in being fulfilled. The Hospitallers of Quebec were at that moment requesting reinforcements from their Mothers in France. The two de Longpré sisters were among the first to offer themselves, especially Catherine who was not old enough to make her profession. Her family became alarmed. The older sister yielded to her parents’ entreaties, but the younger one resisted all pressures. M. de Longpré became annoyed and “petitioned the court” to prevent his daughter’s departure. The novice was adamant and vowed to live and die in Canada if God would let her go there. Her father softened and gave his consent. The nuns, for their part, were reluctant to lose a recruit who gave promise of rendering such great services to the Bayeux convent. At last Catherine took ship for Quebec. She was not yet 16, the minimum age for profession. She was allowed to take ordinary vows, which she did in the chapel of Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Joie at Nantes. At sea she almost died of the plague. After three months on the ocean, she reached New France on 19 Aug. 1648.

At this period Quebec was only a little town in the midst of barbarism. Catherine was lodged in an Hôtel-Dieu that seemed “more like a hut than a hospital.” And what an atmosphere there was in the country! The Iroquois were massacring the Hurons, martyring the missionaries, burning the dwellings, and threatening to destroy the colony. In a letter dated 9 Nov. 1651, Mother Catherine wrote: “We are in no hurry to finish the rest of our buildings, because of our uncertainty whether we shall be staying here for long.”

Mother Catherine soon established for herself a reputation as an exemplary nun: she was considered to be a treasure, she was loved and was thought to be perfect by nature. But her health was so fragile that the Hospitallers of Bayeux became concerned and invited her to return to France. The young nun declined these offers: “I am too much absorbed in Canada,” she exclaimed, “to be able to tear myself away. Believe, me, my dear aunt, only death or a general upheaval in this country can break this bond.”

We find her becoming in turn depositary (1659), senior Hospitaller (1663), and mistress of novices (1665). In 1668 the community contemplated electing her superior, but on 20 April of that year she began spitting blood. On 8 May, she died at the age of 36.

After 1668, Mother Catherine’s secrets were brought to light. In Canada, even in Europe, there was talk of the extraordinary occurrences at the Hôtel-Dieu in Quebec. In 1671 Father Paul Ragueneau published La vie de Mère Catherine de Saint-Augustin. At once the public penetrated into the innermost existence of the young nun. Until then she had appeared to be at peace with this world and the next; but suddenly a host of disturbing things were learned about this Hospitaller who had seemed so serene and so intent upon passing unnoticed. What a price she had paid for her saintliness! God had allowed her to be possessed, that is, to be tormented in visible and external fashion by the devil. At times, says Ragueneau, so great a horde of demons assailed Mother Catherine that they seemed as numerous “as the specks one sees in the air in sunlight” (p.160). In the presence of these dark angels, she underwent a kind of psychological dissociation from herself: despite her refined nature she was cohabiting with depraved beings. This ontological torture was aggravated by a sort of moral dualism: on the one hand she felt an unspeakable loathing for the slightest impurity; on the other hand she felt as if sin were imprinted in her heart and she regretted that she was not utterly impious, not “fully and completely like the demons” (p.125). It is not surprising that she skirted the abyss of despair: “I experienced a violent desire to be damned without delay” (pp.206–7).

Instead of crying for help and begging for deliverance, Mother Catherine advanced to the limit of magnanimity and uttered this pathetic prayer: “My Saviour and my All! If the demons’ sojourn in my body is pleasing in your sight, I am willing that they should stay there as long as you wish; provided that sin does not creep in with them, I fear nothing, and I hope that you will grant me grace to love you for all eternity, even though I were in the depths of hell.” (P.50)

Catherine de Saint-Augustin tells that God gave her as director the Jesuit Father Jean de Brébeuf, another native of Bayeux, who had died in 1649. This missionary had never during his lifetime met Mother Catherine de Saint-Augustin. The nun says that from 1662 on, she frequently received visits from this blessed Jesuit, who was entrusted with guiding, comforting, and at times restraining her in her mortifications. But on certain days even he seemed to elude her. To win him to her, Mother Catherine spoke to him with childlike simplicity: “How happy I am, Father, that you are deriving some small joy and satisfaction now from seeing me thus crucified: be vexed with me as much as you like; I shall always look upon you and love you as my kind and charitable Father.” (P.207.)

On many occasions Mother Catherine stated that it was for Canada, which was in danger of undergoing grave punishments for the crimes being committed there, that she was enduring suffering. This role of assumed victim for the colony has placed Mother Catherine among the founders of the Canadian Church. While others overcame the forest, the rivers, the winter and the Indians, Mother Catherine bore the sins of her adopted country and grappled in close quarters with the powers of darkness.

What are we to think of these unusual revelations? In the first place, Father Ragueneau recounts them in uninspired fashion, in the style of the ancient hagiographers who were more skilful in giving a distaste for virture than in effectively presenting their personages. This first biographer of Mother Catherine advises us, however, that he composed the Vie from the Hospitaller’s own “Journal.” Since the latter document has disappeared, internal criticism is required to evaluate Father Ragueneau’s work. Until this scientific study is made, there are left to us a number of pieces of testimony in Mother Catherine’s favour: the opinions of contemporaries who concur in their praise of the heroic nun.

First of all, the Annales de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec published an obituary notice which should be mentioned. Let us note this paragraph: “This dear Mother died in odour of sanctity, 8 May 1668, aged 36 years and 5 days, universally mourned by the whole Community and the whole colony as a soul who brought great blessings upon this poor land. She spent 20 years in Canada, where she was a source of great edification to everyone and gave great glory to God by the heroic acts of virtue she accomplished there, although externally she led an ordinary life that carefully concealed the treasures of grace that God had bestowed upon her.”

Further on, the annalist noted that the Vie had the merit of displeasing the members of Port Royal “who contemplated submitting it to the Sorbonne” apparently in the hope of having it condemned.

Here is how Mother Marie Forestier de Saint-Bonaventure, superior of the Hôtel-Dieu in 1668, announced the death of her daughter in religion to the Hospitallers of Bayeux: “We cannot possibly convey to you our sentiments at such a loss, for we have lost what we shall never regain, the best and most lovable person one might ever hope to see: the best formed and most attractive disposition one can conceive of; a girl who was as quiet, charitable, and prudent as anyone could imagine: her virtue was as exceptional as God’s behaviour with her was unusual. Our grief is so legitimate and so palpable that we can speak of it and think of it only with tears.”

Bishop François de Laval* for his part wrote personally to the Superior of the Hospitallers of Bayeux: “My dear Mother, there is every reason to glorify God for the course of action he has followed with respect to our Sister Catherine de Saint-Augustin. She was a soul he had chosen in order to impart to her very great and very special blessings. Her saintliness will be better known in heaven than in this life, for assuredly she is exceptional. She has accomplished much and suffered much with inviolable faithfulness and with a courage that was above the ordinary: her love for her fellow man was able to take in anything, no matter how difficult. I have no need of the extraordinary things which took place within her in order to be convinced of her saintliness; her real virtues make it perfectly known to me.”

His interest aroused by all the marvellous stories which were circulating about Mother Catherine, Father Joseph-Antoine Poncet de La Rivière, a former missionary in New France, consulted Marie de l’Incarnation. [see Guyart]. After the burning of her monastery (30 Dec. 1650), the latter had lived for three weeks at the Hôtel-Dieu in Quebec. This stay had allowed her to meet Mother Catherine and to develop an admiration for her. Mother Marie de l’Incarnation was nevertheless cautious in her reply to Father Poncet: “I am quite unable to tell you my feeling about such extraordinary matters, as you ask me to, and I beg you to excuse me from doing so, seeing that persons of learning and virtue are suspending judgment on the question and are continuing in doubt, not daring to give credence to unusual visions of this type. Reverend Father Ragueneau is a scholar in these matters and he considers her blessed, because she has always been faithful in her duty, and has never yielded to the demon, over whom she has always been victorious. I am of the opinion that this fidelity in her obligations and her struggles makes her great in heaven, and I rely on that more readily than on the visions that I hear about. And what has further astonished persons of virtue and experience is the fact that she never said a word about her behaviour to her superior, who is a very enlightened person of great, experience and of exceptional virtue.” Further on, Marie de l’Incarnation was more explicit: “It was not for lack of loyalty or submissiveness that she kept all that secret, but because of the order she had received from her directors in view of the nature of her case which might well have been upsetting.”

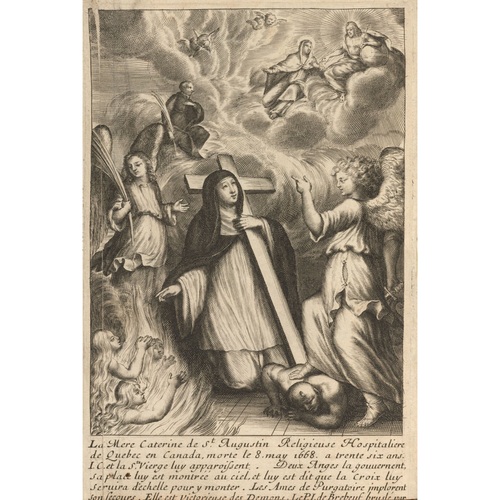

By the overflowing activity of her life as well as by her discretion and her good humour, Mother Catherine proved that she was by no means a hysterical woman. Aware that he was writing a book likely to arouse controversy, Father Ragueneau began it by a foreword. In this preliminary vindication, Mother Catherine appeared as a well-balanced person, secure from all the snares of the imagination. The Vie began with a symbolic picture engraved at Bishop Laval’s request. At the bottom were to be seen Satan and the souls in purgatory; in the centre, angels helped Mother Catherine to support a large cross; in the sky Father Brébeuf was holding a palm in his hand; at the very top were the Virgin and Our Lord. This picture is a sort of condensed biography, which makes no impression on the 20th century. Instead of this complicated iconography, we prefer the likeness of the delicate face of Mother Catherine de Longpré that adorns the little private chapel in the Hôtel-Dieu in Quebec. Lively and wide-awake, this delightful young Norman girl hurled herself into paradise at a heroic pace. She must be depicted above all as a missionary on foreign soil, as a nurse, as an enterprising woman who died with a “Te Deum” on her lips. In that way she will emerge gloriously from the shadows, reassuring both theologians and psychiatrists.

Marie Guyart de l’Incarnation, Lettres (Martin); Lettres (Richaudeau). JR (Thwaites), XXXII. Juchereau, Annales (Jamet). Paul Ragueneau, La vie de Mère Catherine de Saint-Augustin (Paris, 1671). P.-G. Roy, La Fille de Québec, I, 207–8. Les Ursulines de Québec, I, 9.

Cite This Article

Marie-Emmanuel Chabot, o.s.u., “SIMON DE LONGPRÉ, MARIE-CATHERINE DE, dite de Saint-Augustin,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 4, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/simon_de_longpre_marie_catherine_de_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/simon_de_longpre_marie_catherine_de_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Marie-Emmanuel Chabot, o.s.u. |

| Title of Article: | SIMON DE LONGPRÉ, MARIE-CATHERINE DE, dite de Saint-Augustin |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | December 4, 2025 |