Source: Link

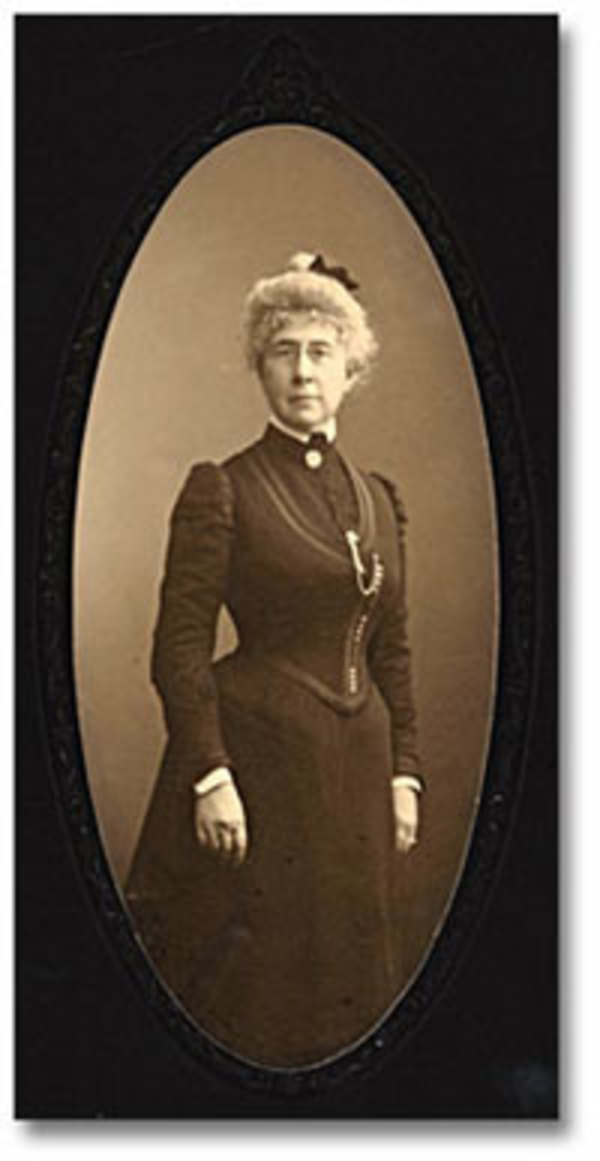

SNIVELY, MARY AGNES, educator, nurse, and nursing-school administrator; b. 12 Nov. 1847 in St Catharines, Upper Canada, daughter of Martin Snively and Susan M. Copeland; d. unmarried 26 Sept. 1933 in Toronto.

Mary Agnes Snively’s father, of German descent, was born in Niagara Falls, Upper Canada. He ran a furniture-making and undertaking business in St Catharines. Her mother’s parents had emigrated from Ireland when Susan was young. Mary Agnes, the third of four surviving daughters, had a happy childhood and was very attached to her grandmother Copeland, whose strong sense of personal religion had a great impact on her.

After graduating from high school, Snively accepted a teaching position with the public-school board in her hometown. According to an inspector, she was an excellent instructor and faithful worker who exerted a “wonderful moral influence in dealing with children.” She taught for close to two decades. In the early 1880s her friends and former fellow teachers Louise Darch and Isabel Adams Hampton urged her to follow their example and attend New York’s Bellevue Hospital Training School for Nurses, which was modelled on Florence Nightingale’s school in England. Initially Snively’s widowed mother would not allow her daughter to enrol, but she relented after a visit from Hampton, and Snively entered Bellevue in October 1882. Upon completion of her program, she was hired on 1 Dec. 1884 as lady superintendent at the Toronto General Hospital, where the Training School for Nurses had been established three years earlier by Dr Charles O’Reilly* and Snively’s first predecessor, Harriet Goldie.

Snively found conditions at the TGH less than satisfactory. The hospital had about 400 beds, with only 7 nurses in charge of the wards and 27 nurses in training. There were no set schedules for work and study, no proper record-keeping systems, and no policies for obtaining supplies. Nurses’ living conditions were grim: they occupied poorly heated rooms wherever there was space in the building, slept on straw beds, and ate meals opposite the boiler-room in the basement.

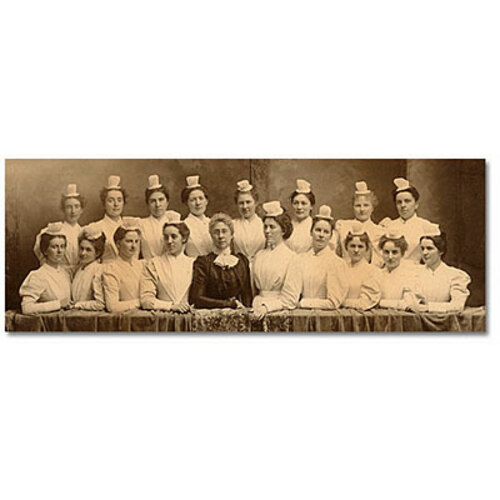

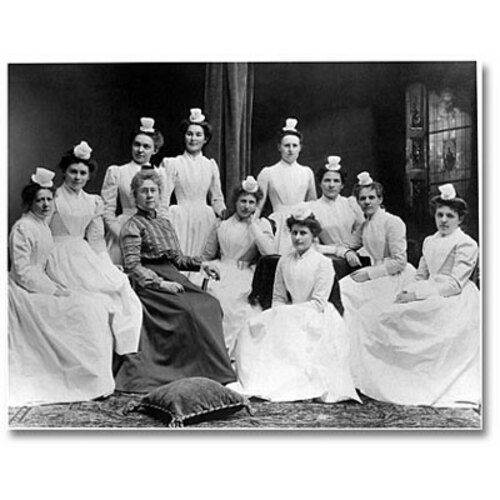

With the indomitable will that would characterize her career in nursing leadership, Snively began instituting changes. She reorganized the curriculum, introducing regular lectures by physicians and courses on subjects such as nursing ethics, and implemented a written examination at the end of the two-year training period. Dishwashing and other menial tasks were reassigned to others so that the students could concentrate on medical responsibilities. Determined to improve their lives and aware that refinement and comfort would be essential to transform the image of nursing and attract middle-class women, she convinced the hospital board to erect a nurses’ residence. The new building, which included a dining room, parlours, and two libraries, was completed in July 1887 (starting in 1897 she would campaign for a larger residence, which was constructed in 1900). Thanks to gradual improvements, well-educated young women began to show interest. By 1891 there were 600 applicants, of whom 57 were accepted. Like her contemporary, Gertrude Elizabeth Livingston*, who had become head of the nursing school at the Montreal General Hospital in 1890, Snively focused on continually raising the reputation of her school and the profession. By 1894 the Toronto General Hospital Training School for Nurses was the largest in the country, and graduates were employed across Ontario and abroad. That year Snively helped establish the hospital’s Nurses’ Alumnae Association, the first of its kind in Canada, and was elected chair.

In 1897 Snively was named president of the Society of Superintendents of Training Schools for Nurses of the United States and Canada, whose members worked together to determine programs of study. Snively, who had recently extended the TGH training program to three years, believed that to achieve high standards in morals, ethics, and education throughout Canada, nurses needed to be organized and consolidated: she advocated a fixed curriculum, a uniform examination, and a registration process, and to this end she brought together provincial organizations and alumnae bodies to form the Canadian National Association of Trained Nurses in 1908 (it would become the Canadian Nurses’ Association in 1924). She was named the CNATN’s first president, and Flora Madeline Shaw* of the Montreal General Hospital Alumnae Association was appointed secretary-treasurer. Snively then forged ties between the CNATN and the International Council of Nurses, on whose executive she had served since its inception in 1899. The CNATN was officially welcomed into the ICN in 1909 at its triennial meeting in London, England. As president of the Canadian organization, Snively was invited to lay a wreath at the tomb of Queen Victoria and give a short address.

Snively was known for her great kindness and dedication to the welfare of patients. She was a strong disciplinarian with unrelenting ideals who placed great value on enthusiasm, courage, and inspiration. In a speech delivered at a 1904 graduation ceremony in Cleveland, Ohio (later printed in the American Journal of Nursing), she spoke of the profession as a mission, calling it “the noblest, most womanly, most Christ-like, of all the avocations open to women.… What makes a woman a good nurse? Practice. What makes a woman a good woman? Practice.… Life is not a holiday, it is an education. The world is not a playground, it is a school-room, and character develops in the stream of the world’s life.” Snively exemplified this conviction, as well as the motto adopted in 1907 by the TGH Training School for Nurses, Augere quam acquirere, which it translated thus: To be is greater than to acquire.

On 1 Dec. 1909 the Nurses’ Alumnae Association of the TGH held a reception celebrating the 25th anniversary of Snively’s appointment. She was presented with a silver card-case and a cheque for $1,000. Then board chairman Joseph Wesley Flavelle shared the devastating news that Snively had decided to retire. He announced that the hospital would provide her with a lifetime annuity of $700. In a note written to her mentor that day, graduate Janet Neilson expressed her admiration: “Never have we seen you choose the easiest way because it was the easiest. We have always seen you brave unpopularity when the right issue was at stake. Time and time again have we seen you ignore physical and mental weariness and shoulder your burden, and we have always known you to turn a tender and pitying ear to the cry of pain. However far short we have fallen from the ideal you have had for us we cannot fail to have been influenced by your spirit.” When she left her position the following year Snively handed on to her successor, Robina Lamont Stewart, a school known internationally for its high standards and one which had influenced nursing across Canada and in the United States through those described by historian Pauline O. Jardine as its graduate “missionaries.”

Snively remained active. After her retirement she travelled abroad for 14 months, during which time she attended the 1911 International Council of Nurses meeting in Cologne, Germany. Maintaining ties with the CNATN, she served as archivist and honorary president, and she was made a life member in 1921. She continued to devote herself to the welfare of others through church and social work. For many years she taught a Chinese Sunday-school class, took on the presidency of the Woman’s Missionary Society of St James Square Presbyterian Church, and directed a nursing mission that cared for the city’s poor. Sacrificing personal comforts, she financially supported aspiring medical students and missionaries in Formosa (Taiwan), India, and China, and also funded a children’s school in China.

Upon retiring Snively had moved from her quarters in the nurses’ residence to a boarding house. In 1931 the TGH’s trustees arranged for her to enter the new Private Patients’ Pavilion. It was there that she died at age 85 following a two-month illness. The “Mother of Nurses in Canada,” as she was remembered in the Canadian Nurse, was laid to rest in Victoria Lawn Cemetery, St Catharines. In Jardine’s words, she left a remarkable legacy: “higher education, professional ethics, devotion to duty, and an acquired public image – now nurses were recognized as both ladies and professional women.”

Mary Agnes Snively published several articles, reports, and speeches, including: “Address of President Mary Agnes Snively: fifth annual convention of the Superintendents’ Society, 1898, Toronto, Canada,” in Legacy of leadership …, ed. Nettie Birnbach and Sandra Lewenson (New York, 1993), 34–39; “President’s address,” Canadian Nurse (Toronto), 4 (1908): 524–28; and “What manner of women ought nurses to be?,” American Journal of Nursing (New York), 4 (1903–4): 836–40.

Snively’s portrait was presented to the Toronto General Hospital in 1925 by the Nurses’ Alumnae Assoc. Painted by John Wycliffe Lowes Forster, it originally hung in the nurses’ residence. It is now in the Univ. Health Network Nursing Centre, located in the hospital’s Eaton Building.

Information about Snively can be found in the City of Toronto Arch., Fonds 234 (Alumnae Assoc., School of Nursing, Toronto General Hospital); see in particular ser.895, 896, 948, and 1206 as well as the archives’ web exhibit “That I may be of service – guiding hands.”

Daily Mail and Empire (Toronto), 2 Dec. 1909, 27 Sept. 1933. J. E. Browne, “A daughter of Canada,” Canadian Nurse (Winnipeg), 20 (1924): 617–20, 681–84, 734–36; “In memoriam: Miss Mary Agnes Snively,” Canadian Nurse (Montreal), 29 (1933): 567–70. Elvie Follett, “Mary Agnes Snively,” Toronto General Hospital, School of Nursing, Alumnae Assoc., Quarterly (Toronto), fall 1984 (copy at the City of Toronto Arch., fonds 234). History: the School for Nurses, Toronto General Hospital …, ed. M. I. Lawrence ([Toronto, 1931]). P. O. Jardine, “An urban middle-class calling: women and the emergence of modern nursing education at the Toronto General Hospital, 1881–1914,” Urban Hist. Rev. (Toronto), 17 (1988–89): 177–90. Diana Mansell, “Mary Agnes Snively: realistic optimist,” Canadian Journal of Nursing Leadership (Toronto), 12 (1999), 1: 27–29. Natalie Riegler, “Mary Agnes Snively, 1847–1933: leading the way,” Registered Nurse (Toronto), May–June 1999: 5–7 (copy at the City of Toronto Arch., fonds 234).

Cite This Article

Diana Mansell, “SNIVELY, MARY AGNES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/snively_mary_agnes_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/snively_mary_agnes_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Diana Mansell |

| Title of Article: | SNIVELY, MARY AGNES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2017 |

| Year of revision: | 2017 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |