TRIPLETT, JAMES OSCAR (also known as James Oscar and Oscar James), homesteader and asylum inmate; probably b. in the 1870s, possibly the son of James Triplett and Nancey Shelton of Hartford, Putnam County, Mo.; d. 13 Dec. 1918 about 20 miles northwest of Rocky Mountain House, Alta.

James Oscar Triplett’s origins are uncertain, although it appears that he arrived in western Canada around 1912 from Missouri. A sister, Daisy L. Houston, was living there when Triplett died. There exists a suggestion that at some point before coming to Alberta he had resided in insane asylums in Montana and Idaho, both as an inmate and as a guard-trustee. At his death it was reported that these experiences had been recorded in a memoir entitled Hell and repeat, copies of which have failed to surface. A final detail is that Triplett had a registered homestead west of Rocky Mountain House, although the land remained unimproved at the time of his death.

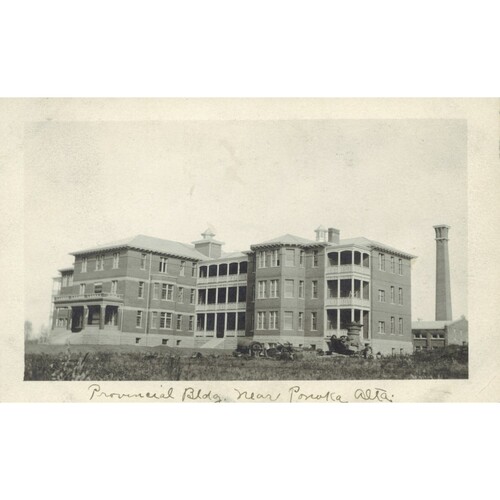

Aimless wanderings punctuated by bouts of insanity would mark Triplett’s life in central Alberta after 1912. His presence there was testament to the attraction of western Canada for all types of people, some of whom apparently sought escape from real and imagined pressures elsewhere. Prior to the opening in 1911 of the Hospital for the Insane near Ponoka, the first such institution in Alberta, those found insane had been sent to Manitoba, first to the Stony Mountain Penitentiary and then to the Brandon asylum. Even with the Ponoka hospital, where treatment was largely custodial, the province was ill-equipped to care for individuals unable to find peace of mind. Some committed suicide; others, apparently in severe states of depression, murdered family members; still others received treatment for paranoia at Ponoka and were released, only to suffer continued agitation.

Shortly after his arrival in Alberta, Triplett acquired a reputation for being an erratic character. It was not until 1917, however, that he gained the dubious honour of being the first individual to be committed by the newly established Red Deer detachment of the Alberta Provincial Police. This incarceration followed a series of events in which Triplett, detained in the police lock-up at Rocky Mountain House, escaped and bolted, naked, down the main street before he was reapprehended. The police sent him to Ponoka for observation. His only treatment was confinement since it was assumed that his paranoid delusions would, in time, return. None the less he was discharged on probation on 20 June 1918, having experienced a recovery of sorts. He returned to Rocky Mountain House. By August his behaviour compelled the local physician, James Binnie Miller, to contact both the provincial police and Edleston Harvey Cooke, the medical superintendent at Ponoka, in search of some means of dealing with Triplett. The police could not act until he had actually broken the law, and Cooke does not appear to have responded to Miller’s concerns. Although this crisis passed, in mid December Miller’s fears about Triplett’s behaviour were realized.

Beginning on the evening of 12 December, Triplett terrorized a number of farms west of Rocky Mountain House. Brandishing a double-edged axe, he appeared at Ray and Lois Temple’s farm and, after making threats against Ray, who was absent on a hunting trip, he was persuaded to leave by Lois. Retreating to Jacob Stutesman’s nearby farm, he harangued Stutesman all night, destroyed almost everything in his cabin, howled, and ran around naked, despite freezing temperatures. After attempting to strangle Stutesman, Triplett left on the afternoon of the 13th. Stutesman then raced cross-country to warn Lois Temple that Triplett was still on the loose.

Temple was understandably agitated. Stutesman agreed to stay and began helping with chores. Suddenly Triplett appeared. He stormed around the yard, threatening Stutesman and Temple with violence, killing chickens, and trying to set the cabin roof on fire. Stutesman shot at him at least four times and then gave chase. He caught up to him at the front door, where Triplett was stooped over attempting to force an entry. Stutesman shouted to Temple that Triplett was coming and, in response, she yelled to stand back or she would shoot. As the doorknob turned, she fired through the door. The bullet ricocheted off Triplett’s thumb and struck him below the eye; he was dead before he hit the ground.

The subsequent police investigation and coroner’s inquest exonerated Lois Temple, who, the coroner’s jury found, had acted in defence of her life and honour, and her child. More pointedly, it requested that a special inquiry be launched into the release of Triplett from Ponoka and for “the fixing of blame for permitting a criminally insane man to be at large to terrorize a community where his inclinations were so well known.” In defending the decision to release Triplett, E. H. Cooke simply suggested in January 1919 that “all cases of insanity are certain to relapse sooner or later.” Such opinions would hardly have comforted Jacob Stutesman or Lois Temple.

PAA, 67.172/1192. Red Deer Advocate (Red Deer, Alta), 20, 27 Dec. 1918; 3 Jan. 1919. I. H. Clarke, “Public provisions for the mentally ill in Alberta, 1907–1936” (ma thesis, Univ. of Calgary, 1973). The days before yesterday: history of Rocky Mountain House district, ed. Freeda Fleming and Angie Egerton (Rocky Mountain House, Alta, 1977).

Cite This Article

Jonathan Swainger, “TRIPLETT, JAMES OSCAR (James Oscar, Oscar James),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/triplett_james_oscar_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/triplett_james_oscar_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jonathan Swainger |

| Title of Article: | TRIPLETT, JAMES OSCAR (James Oscar, Oscar James) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |