Source: Link

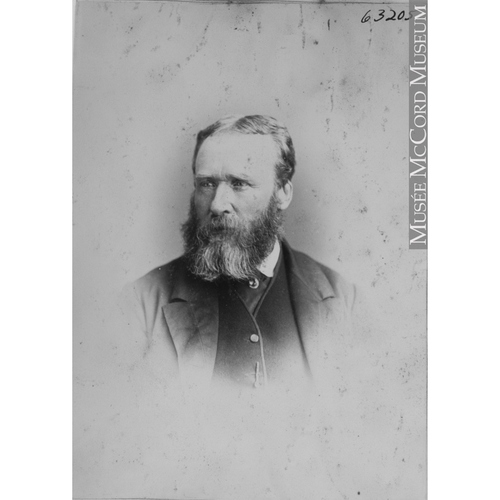

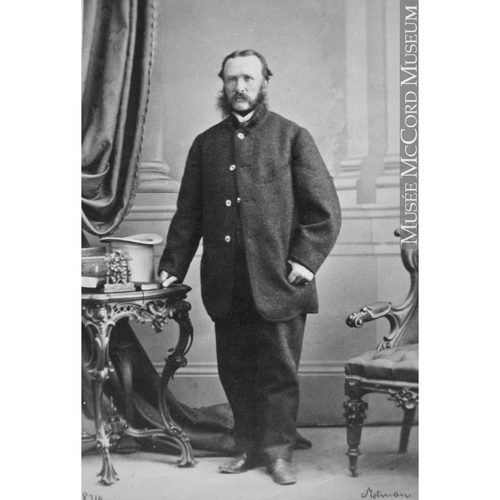

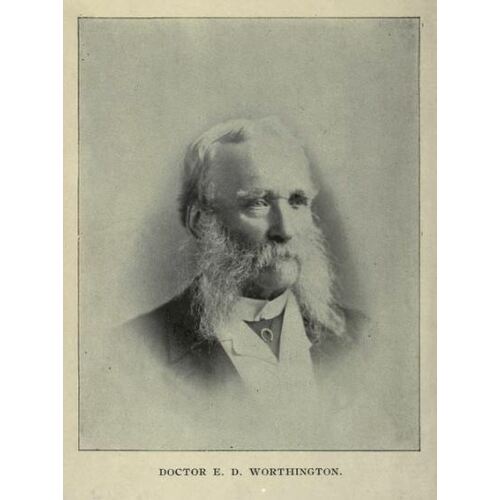

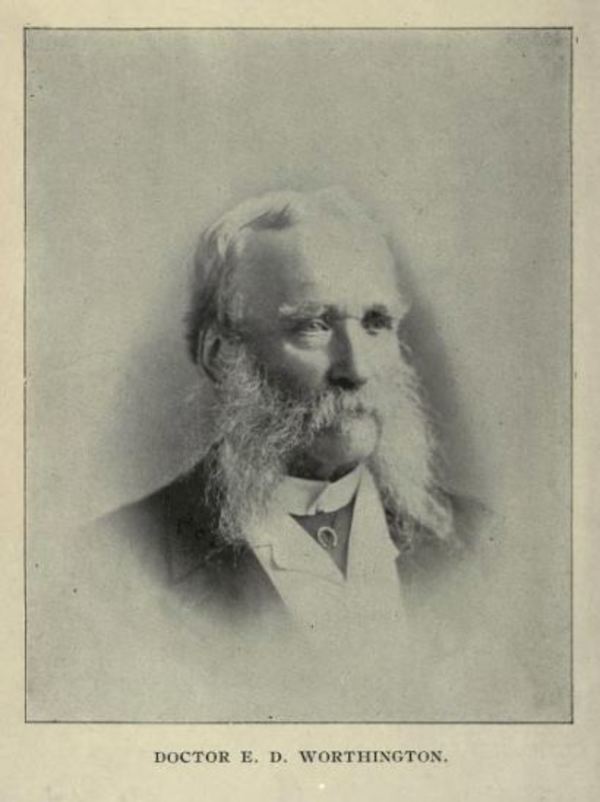

WORTHINGTON, EDWARD DAGGE, physician, surgeon, militia officer, and author; b. 1 Dec. 1820 in Ballinakill (Republic of Ireland), son of John Worthington and Mary Dagge; d. 25 Feb. 1895 in Sherbrooke, Que.

Edward Dagge Worthington immigrated to Quebec with his parents in 1822. Because they were poor, it seems, his early education was by his own admission “neglected.” In August 1833 he was indentured for seven years to James Douglas*, a distinguished Quebec surgeon; among Worthington’s fellow pupils was George Edgeworth Fenwick, who became a lifelong friend. Apprenticeship was then the common way to pursue a medical education in the Canadas, the only medical school being the McGill College medical faculty in Montreal. In addition to winter courses in practical anatomy and the day-to-day training involved in following his master, Worthington had the benefit, from 1837 to 1840, of lectures at the Marine and Emigrant Hospital, where Douglas taught surgery and anatomy and Joseph Painchaud* obstetrics and the theory and practice of medicine.

Dissection of human bodies was a necessary part of the formation of a medical student. If the body had been acquired under acceptable circumstances – “the munificient gift of a criminal,” “the death of a pauper whom nobody owned,” or “an occasional inquest or post-mortem examination” – the dissection could be conducted with a considerable degree of domesticity in the arrangements. “When one settles down to the quiet dissection of an arm or a leg, or the following out of the distribution of the branches of blood vessels or nerves,” Worthington later recalled, “it is rather pleasant than otherwise, especially as often happened in those ‘good old days,’ when the ladies of the house would bring in their work, sit down for a pleasant chat, and manifest a deep interest in the surroundings.” Socially acceptable sources of subjects failed to meet the demand, however, and students resorted to nocturnal body-stealing, often with the assistance of a “resurrectionist,” hired for a few dollars and a bottle of gin. The macabre quests were sometimes made “at great personal risk.”

Worthington also recalled that during his student days (and for years after) bleeding and tooth-pulling were the panaceas of medical practice and “perquisites from time immemorial, to the students in the absence of a doctor.” Bleeding was often done at the patient’s request since “it was considered the correct thing to be bled at least every spring.” In the port of Quebec sea-faring men requested the operation in the spring and in the fall, “the first to enable them to withstand the summer’s heat, and the latter the winter’s cold.” Women were bled from the foot so that no scar would show. When bleeding failed to prevent a disease, bleeding was used to cure it, and if the first bleeding failed “a second bleeding followed, and a third, until the disease – or the patient – succumbed!”

In 1837 Worthington served as a private in the Quebec Regiment of Volunteer Light Infantry. Three years later he was appointed acting assistant surgeon to the 56th Foot. He was posted to the 68th Foot in 1841, but he resigned his commission that year to attend medical classes at the University of Edinburgh. Finding that his education in Lower Canada did not qualify him for admission there, he attended lectures at the Medical School, Edinburgh, and the Eye Dispensary of Edinburgh until April 1843. In May he was granted an md by the University of St Andrews, and in June he became a licentiate of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow; possibly he was also a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, although that cannot be confirmed. His fellow students at this time included Charles Tupper* and Daniel McNeill Parker*.

Back in Lower Canada, Worthington was licensed on 9 Aug. 1843. He immediately settled in Sherbrooke, becoming one of four doctors there who served the town and the countryside for a radius of 20 miles. Two were considerably older than Worthington and, being the most recent arrival, he inherited much of the hated night practice. He was an active and innovative practitioner, both a physician and a surgeon, as was the custom in North America. He used surgical anaesthesia very early after its discovery, amputating a leg on 10 March 1847 under ether and using chloroform in January 1848; the first anaesthetic had been administered in Boston in October 1846. Worthington published the results of these two operations in the British American Journal of Medical and Physical Sciences for 1847 and 1848, and later he published extensively in the Canada Medical Journal and Monthly Record of Medical and Surgical Science. In 1854 Bishop’s College, Lennoxville, conferred on him an honorary ma.

By 1860 he had nearly all the surgical practice in the Eastern Townships, and he was frequently called in from long distances for consultation. He was the first president of the St Francis District Medical Association. His dedication to public medicine was noted with gratitude by the community which, in 1865, gave him a solid silver tea service for his free care of the poor and on another occasion a gold watch for successfully stemming an outbreak of smallpox in Sherbrooke. So respected was Worthington that even an accusation by a local judge that he had carried out an autopsy carelessly during a trial for murder in 1871 seems not to have damaged his reputation. Worthington defended himself in a pamphlet, A review of the trial of Andrew Hill for murder, and was approved by the News and Frontier Advocate of Saint-Jean and, apparently, the Canada Medical Journal, edited by Fenwick.

Indeed Worthington had become prominent on a provincial scale. He had been named a governor of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Lower Canada in 1860. Seven years later he participated in the founding of the Canadian Medical Association. He was a member of several committees of the association in 1872 and offered a gold medal to be presented by it to the author of the best essay on zymotic diseases in Canada; however, no essays were submitted and the prize lapsed. In 1877 he was the association’s vice-president for the province of Quebec. Meanwhile, in 1868 he had received a degree of md, cm (ad eun.) from McGill College. In 1878, however, he was again involved in controversy when he and Fenwick were brought before a grand jury for having irregularly obtained medical licences from the College of Physicians and Surgeons the previous year. The irregularity was more technical than substantial, and the grand jury rejected the case, even though the prosecution had been supported by the president of the college, Jean-Philippe Rottot*. Worthington angrily resigned as a governor of the college over the incident.

Worthington had maintained his early military involvement, serving professionally during the Fenian raids in 1866 and 1870. Attached to the 53rd (Sherbrooke) Battalion of Infantry since its formation in 1866, he retired from it with the rank of surgeon-major in 1887. He also dabbled in business, being an incorporator of the Magog Petroleum Company in 1866. A member of the Church of England, he was at one time a delegate to the provincial synod. In politics he was a Conservative.

On 16 Oct. 1845 Worthington had married Frances Louisa Smith, daughter of businessman Hollis Smith*. They had eight children, of whom at least five survived childhood and to whom Worthington was clearly an affectionate father. A daughter married William D. Antrobus, an inspector in the North-West Mounted Police, one son became a notary, and another, Arthur Norreys, followed in his father’s footsteps before being elected to parliament; both sons served in the 53rd Battalion.

By 1892 Worthington had become incapacitated by illness, and to occupy himself he wrote his reminiscences, which were published in the Medical Age (Detroit). Largely anecdotal but revealing of medical practices in the 19th century, they were aptly described by the editor of the review as “exquisite bits of word-painting and quaint humour” and were brought together in book form as a memorial to him after his death in February 1895.

Edward Dagge Worthington is the author of A review of the trial of Andrew Hill for murder before the Hon. Edward Short, J.S.C., at the term of the Court of Queen’s Bench, held at Sherbrooke, P.Q., in March, 1871 (Sherbrooke, Que., 1871), Reminiscences of student life and practice (Sherbrooke, 1897), and articles on medical subjects published in British American Journal of Medical and Physical Science (Montreal) and in Canada Medical Journal and Monthly Record of Medical and Surgical Science (Montreal). A portrait appears in Reminiscences.

AC, Saint-François (Sherbrooke), État civil, Anglicans, St James Church (Lennoxville), 16 Oct. 1845. McGill Univ. Libraries, Osler Library, Acc.479. NA, MG 24, F37; RG 68, General index, 1841–67: 124. James Douglas, Journals and reminiscences of James Douglas, M.D., ed. James Douglas Jr (New York, 1910), 163. Robert Short, An answer to a pamphlet entitled ‘A review of the trial of Andrew Hill for murder . . .’ (Sherbrooke, 1871). Canadian biog. dict. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth). Dictionary of American medical biography . . . , ed. H. A. Kelly and W. L. Burrage (New York, 1928). Abbott, Hist. of medicine. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of the Province of Quebec, 1847–1947 (Montreal, 1947). H. E. MacDermot, History of the Canadian Medical Association (2v., Toronto, 1935–58), 1.

Cite This Article

Charles G. Roland, “WORTHINGTON, EDWARD DAGGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/worthington_edward_dagge_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/worthington_edward_dagge_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Charles G. Roland |

| Title of Article: | WORTHINGTON, EDWARD DAGGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |