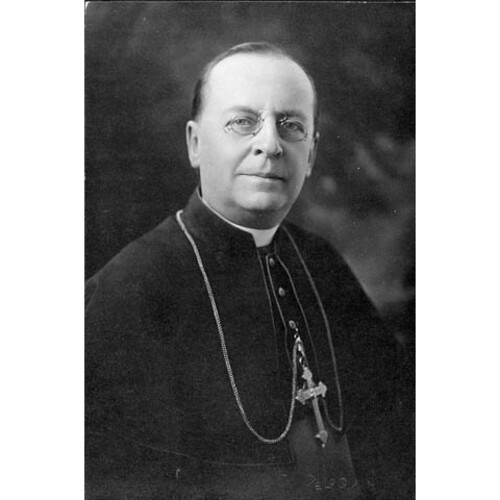

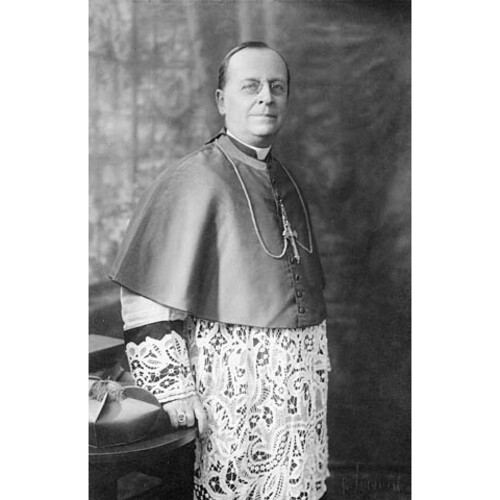

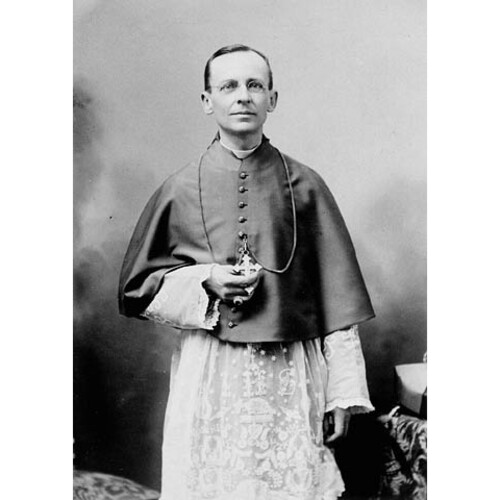

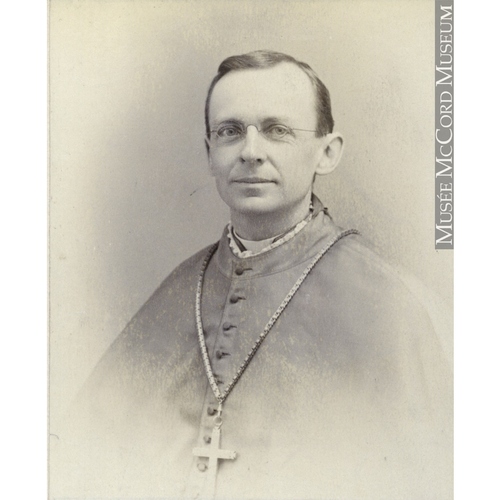

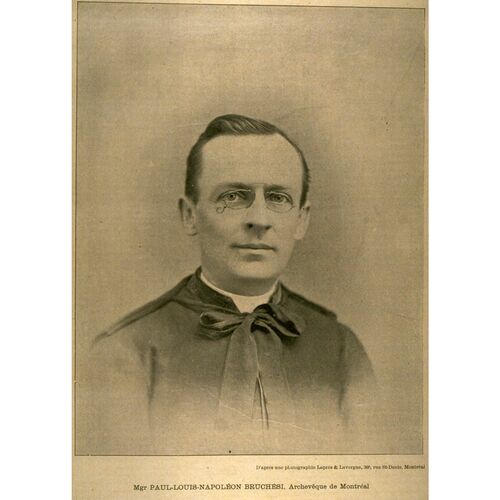

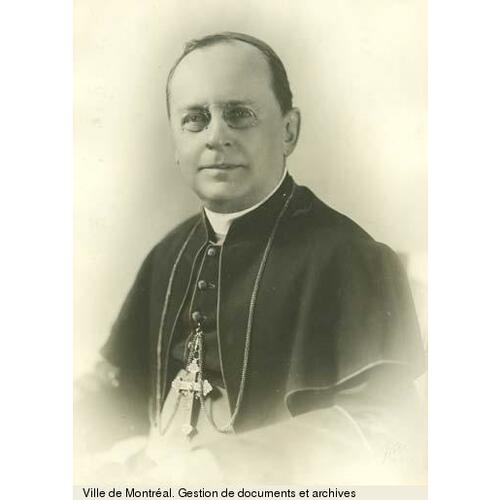

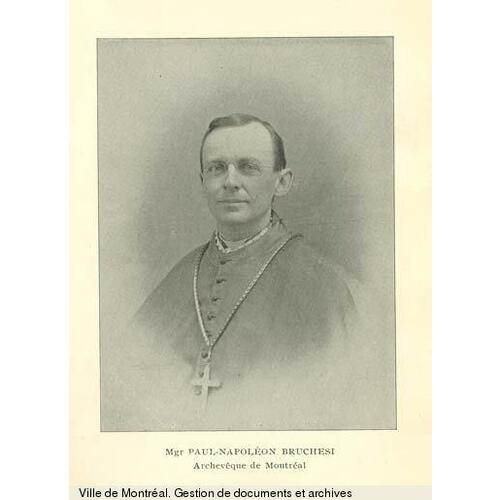

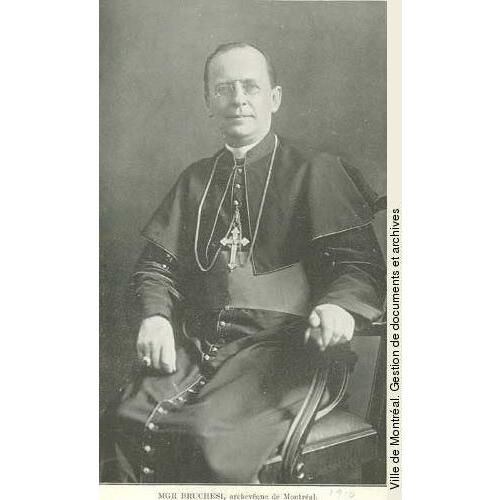

BRUCHÉSI, PAUL (baptized Louis-Joseph-Paul-Napoléon, he called himself Napoléon in childhood), Roman Catholic priest, professor, and archbishop; b. 29 Oct. 1855 in Montreal, son of Paul Bruchési, a grocer, and Marie-Caroline Aubry; d. there 20 Sept. 1939.

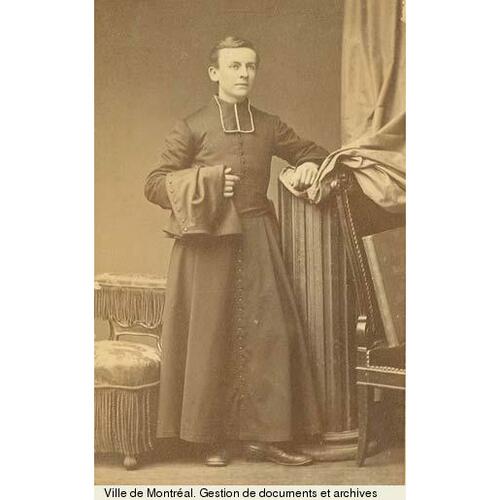

Paul Bruchési was of Italian descent on his father’s side. His grandfather was born in Malta and his grandmother in Naples; they immigrated to Canada around 1810. Paul was the eldest of six children. He attended the Saint-Joseph children’s shelter of the Grey Nuns [see Julie Gaudry*], and then took his primary schooling with the Brothers of the Christian Schools. After pursuing classical studies from 1867 to 1874 at the Petit Séminaire de Montréal, where he was strongly influenced by the Sulpicians and especially by his spiritual director, Clément-François Palin d’Abonville, he went to Issy-les-Moulineaux near Paris to finish the Philosophy program. He began his study of theology at the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice in Paris in 1875–76 and completed it in Rome from 1876 to 1878. Residing at the French seminary, he studied theology at the Roman College and canon law at Apollinaris College. He was ordained priest at the basilica of St John Lateran on 21 Dec. 1878, thanks to a special dispensation because he was underage.

Back in Canada’s biggest city in the summer of 1879, Bruchési served briefly as secretary to Édouard-Charles Fabre*, bishop of Montreal. From 1880 to 1884 he taught theology (dogma) in the faculty of theology at the Université Laval in Quebec City, while also serving as chaplain to the Ursulines. There he made friends with the future archbishop, Louis-Nazaire Bégin*, as well as with a future legislative councillor, Thomas Chapais*, and being on the spot could assess all the complexities of a developing university dispute. Following a period of ill health he left the city in August 1884 and went to France and Rome for rest. On his return to Montreal in September 1885 he was appointed curate for the parish of Saint-Joseph, and then for that of Sainte-Brigide.

Called to the archbishop’s palace in 1887 to become editor of La Semaine religieuse de Montréal (1887–97), Bruchési accompanied Fabre to Rome in 1888–89 as his secretary. This journey would result in the papal bull Jamdudum, which granted the Montreal branch a little more autonomy from the Université Laval in Quebec City, including the right to choose a vice-rector. In 1890 Bruchési became chaplain to the convent of the Religious of the Sacred Heart and to the Pensionnat Mont-Sainte-Marie. The following year he was made a canon and thereafter he was entrusted with more important assignments: as ecclesiastical superior for the Sisters of St Anne (1891–1920), the provincial government’s commissioner at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893), and president of the Montreal Catholic School Commission (1894–97).

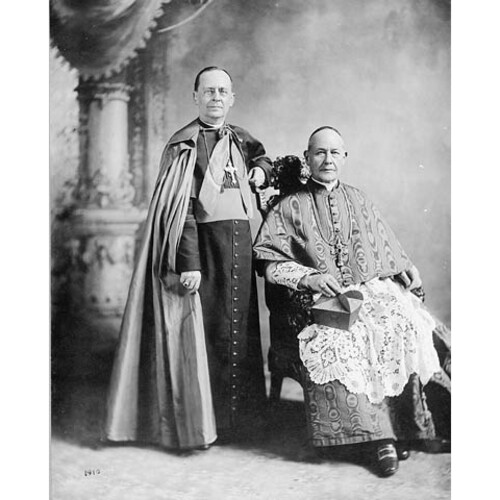

Archbishop Fabre died on 30 Dec. 1896; on 25 June 1897 Canon Bruchési was named the new archbishop of Montreal, in part through the support of Archbishop Bégin, who at the time was the administrator of the diocese of Quebec. Bégin would officiate at Bruchési’s consecration in the Montreal cathedral on 8 August. The new archbishop was introduced as cultured, courteous, and spiritual. He left immediately for Rome, stopping on the way at Paray-le-Monial in France, where he placed his episcopate under the patronage of the Sacred Heart, to which he vigorously promoted devotion early in his career as archbishop. A few financial questions preoccupied him as he took up his duties: the cathedral’s debt, of which $200,000 remained to be paid in 1898, and the reorganization of the Caisse Ecclésiastique, which he transformed in 1898 into the Union Saint-Jean, an association to assist sick or retired priests.

But it was on the great politico-religious questions of the day that, from the beginning, Bruchési left a significant mark. Having won the provincial election of 1897, the Liberals under Félix-Gabriel Marchand* introduced a bill to restore the Ministry of Public Instruction. Strongly opposed to this measure, Bruchési succeeded in having it condemned in Rome, where he was staying at the time. Despite this opposition, it was passed by the Legislative Assembly on 5 Jan. 1898. On his return from Rome Bruchési intervened with his friend Chapais, who managed to have the bill blocked in the Legislative Council on 10 January.

At the federal level, ever since the election of the Liberals had made Wilfrid Laurier* prime minister in 1896, the Manitoba schools question and the Laurier–Greenway agreement had monopolized attention. Frequently consulted on these issues, Rome published on 8 Dec. 1897 the encyclical Affari vos, which called for appeasement and moderation. It was Bruchési who prepared the letter that accompanied the encyclical; signed by Bégin, it also urged a return to calm. Laurier was pleased with it. On 13 July of the following year he wrote to his friend Abbé Jean-Baptiste Proulx*: “Mgr Bruchési certainly shares the pope’s sentiments, and I believe that Rome understands the necessity, the absolute necessity, of putting an end to the period of curses, excommunications, insults, [and] quarrels. The pacifying voice of Mgr Bruchési will be listened to more [carefully] in Rome than all those that have been heard there so far from this country.” The result was that Bruchési would play a central role in the negotiations on the Manitoba question, and would maintain ever-closer ties with Laurier, even to the point of bringing him back in 1899 to the practice of religion. From then on there would be a firm understanding between the two men, and a relationship based on mutual trust.

The initial phase of Bruchési’s administration was a period of rather striking achievement, ending with the International Eucharistic Congress of 1910. In his relations with Montreal and its people, the archbishop championed the raising of a monument to Bishop Ignace Bourget* that would be unveiled on 24 June 1903. The city’s contribution to this monument was to result in some tension, which would become much more acute over the question of the municipal library. It would finally be opened in 1917 after more than 20 years of debate. Labour issues would also be of great concern to the archbishop. The socialist movement was quite strong in the metropolis and on 1 May, a significant day, there were demonstrations, particularly in the years from 1903 to 1907. These activities were punctuated by strikes: streetcar conductors and longshoremen in 1903, carpenters and plasterers in 1905, and longshoremen and truck drivers in 1907. Bruchési’s offers to act as arbitrator would be accepted in 1905 and 1907. Leading working-class figures came to Montreal: Samuel Gompers (president of the American Federation of Labor) in 1903 and James Ramsay MacDonald (a British Labour mp) in 1906. The archbishop fulminated against the international unions, but his protests did not prevent these illustrious visitors from being welcomed triumphantly. From 1904 Bruchési invited the workers to celebrate Labour Day on a religious note, and to this end he organized a ceremony in Notre-Dame church. He would make it an annual event, which would soon feature two services: one at Notre-Dame for French-speaking workers and another at St Patrick’s Church for anglophones. Quite obviously the Catholic Church was trying to set the course for the labour movement, a strategy that would lead to the creation of Catholic trade unions in the following decade.

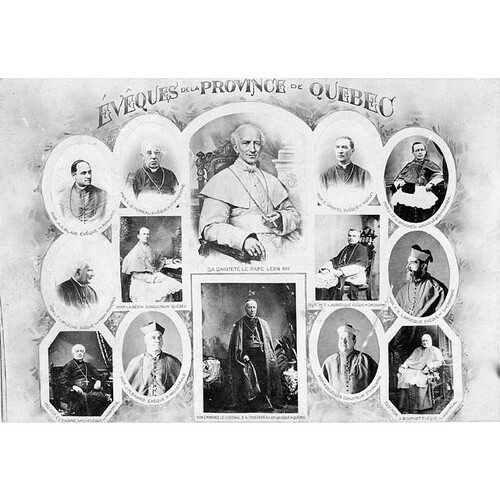

Within the diocese the most important administrative change of this period was the detachment in 1904 of the diocese of Joliette, with Canon Joseph-Alfred Archambeault* becoming its first bishop. At the end of that year Bruchési made his ad limina trip to Rome. His diocese then had nearly 400,000 Catholics, 124 parishes and cures, 670 priests, and 33 religious communities of men and women. Montreal itself, with its suburbs, was home to nearly 300,000 of the faithful. The surrounding countryside required regular visits by the archbishop as well. Hence he had little difficulty in persuading Rome to appoint, for the first time, an auxiliary bishop, Zotique Racicot*, in 1905. After this visit to Rome, where he met the new pope, Pius X, Bruchési resumed his energetic promotion among the faithful of the charity known as Peter’s pence. He organized it more efficiently, with the result that the campaigns held twice a year on its behalf raised some $12,000 in 1906, a sum he found very satisfactory.

The religious communities also drew the archbishop’s attention and he went to see them regularly. In 1898 he personally interceded with the municipal council to request that they continue to be exempt from taxation. Although he was not inclined to welcome the presence of new French congregations, he made a request in 1901 for the Sœurs de l’Espérance, who provided home care for the ill. He also encouraged Délia Tétreault* to found the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception, for which he won approval from Pius X in 1904 during his stay in Rome. It was in fact the pope himself who suggested the name of the community on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the proclamation of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, which was being celebrated at the time. His greatest concern would be the threat of bankruptcy faced by the Clerics of St Viator in 1904 following speculation in real estate by Brother Arsène Charest, the bursar of the Male Institution for the Catholic Deaf and Dumb of the Province of Quebec in Montreal. The archbishop would do everything in his power to maintain the credit ratings of the religious congregations by obtaining a credit guarantee from each and by persuading the government of Lomer Gouin* to pass legislation for a special dispensation to settle the debts of the deaf and dumb institution.

During the same period Bruchési gave encouragement to various other initiatives within the diocese: the founding of the Association Catholique de la Jeunesse Canadienne-Française in Montreal in 1903 [see Joseph Versailles]; the creation of a Catholic women’s organization, the Fédération Nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste in 1907 [see Marie Lacoste*]; and, to counter the opening of a secular high school for girls, the establishment in 1908 of the École d’Enseignement Supérieur pour les Jeunes Filles by Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie [Marie-Aveline Bengle] of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, with whom he had carried on an active correspondence for many years.

Historians are far more familiar with Bruchési’s interventions in the public sector. Much would be made of his actions with regard to censorship, whether they concerned the theatre, the press, or the cinema. In truth, from 1903 until the outbreak of World War I he intervened frequently in public debate to ensure that his views on order and acceptable standards of behaviour would prevail. Worldly pleasures, immoral theatre productions, and especially Sarah Bernhardt met with his condemnation. He took a particularly strong stand during Bernhardt’s visits in 1905 and 1911. In 1905 his precautionary warnings had virtually no effect. In 1911 he protested against two of the plays advertised and the actress substituted others.

The Ouimetoscope, a cinema opened in Montreal by Léo-Ernest Ouimet*, met with his disapproval, especially for showing films on Sunday. Unlike the other Quebec bishops, Bruchési supported the federal Lord’s Day Act in 1906. He forbade, among other things, theatre, concerts, horse races, baseball games, tournaments, and excursions. Nothing was permitted on Sundays but “genuine pilgrimages.” A little earlier he had launched a vigorous crusade against intemperance, assigning the task of spreading the message to the Franciscans [see Hugolin Lemay].

Bruchési’s attitude toward the press was nuanced. He did indeed proscribe Montreal periodicals that were openly anticlerical, such as Les Débats (1903), Le Combat (1904), La Semaine (1909), and La Lumière (1912). His condemnations caused these publications to shut down. In particular, he urged the managers of the major newspapers, especially La Presse, to stay on the right path and avoid sensationalism. It would be an ongoing battle, but Bruchési preferred this kind of intervention to the type advanced in Quebec City by Archbishop Bégin and Bishop Paul-Eugène Roy*, who, along with Abbé Stanislas-Alfred Lortie* and lawyer Adjutor Rivard*, launched a daily, L’Action sociale, in 1907. Bruchési took the view that the partisan political activity into which L’Action sociale would inevitably be drawn was not appropriate for the clergy. In this respect he was in complete agreement with the likes of Laurier and Gouin, and even Henri Bourassa*, who founded Le Devoir in 1910. An independent Catholic newspaper was what pleased the archbishop, who would regularly offer encouragement to Bourassa, without, however, sharing his nationalist views.

Bruchési’s biggest public battle was over public education. His bête noire in this dispute was Godfroy Langlois*, the mla for Montreal, Division No.3 (a riding that would become Montréal-Saint-Louis in 1912), the moving spirit of the radical wing of the Liberal Party, who pressed incessantly for educational reform. He had quickly become identified with the Ligue de l’Enseignement and the L’Émancipation lodge, symbols of the secular ideology in Montreal. In 1905, in order to become premier of Quebec, Gouin had to first reassure the archbishop on the school question. True to his promises, he saw to it that school-reform bills, which came up year after year in different guises (to create the Ministry of Public Instruction, to issue standard school texts, and to elect school commissioners), were blocked. Langlois was also the editor of Le Canada, a Liberal Montreal daily launched in 1903. Exasperated by his anticlerical tone, for years Bruchési called on Laurier and Senator Frédéric-Ligori Béïque to have him dismissed. The last straw was the coverage of Dr Pierre-Salomon Côté’s civil funeral in 1909. Ousted from Le Canada, Langlois started the weekly Le Pays in Montreal at the beginning of 1910.

Gouin did not yield to Bruchési on every point, however, even on the subject of education. He sought a balance between the archiepiscopal stance and that of the radical wing of his party, to which he had previously belonged. Thus in 1907 he decided to set up two technical schools (one in Montreal and the other in Quebec City) and the École des Hautes Études Commerciales de Montréal, all non-sectarian institutions. Bruchési did not object provided that Langlois’s bills were rejected.

The archbishop took a firm position on another public issue: marriage. In 1901 the judicial decision of John Sprott Archibald recognizing the marriage of two Catholics, Édouard Delpit and Marie-Berthe-Aurore-Jeanne Côté, which had been performed by a Protestant minister, elicited strong protests from the prelate against what he called clandestine marriages [see Sir François-Xavier Lemieux]. The controversy led, in 1907, to the pontifical decree Ne temere, which made it compulsory for Catholics to be married by a Catholic priest. The matter would arise again in 1911 in the case Hébert v. Clouâtre & Clouâtre: the next year Bruchési spoke out against the judgement of Napoléon Charbonneau, who sat on the Superior Court, which was taken to the Supreme Court of Canada. Eventually, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London ruled that the question of marriage fell within the jurisdiction of the provinces, with the result that Bruchési obtained the desired amendments to the marriage laws from Gouin. The good relationship produced good results.

This first period of Bruchési’s administration concluded with what might be called his triumph: the International Eucharistic Congress in Montreal from 6 to 11 Sept. 1910. Bringing together a papal legate, more than 100 archbishops and bishops, as well as thousands of priests, the congress was an uninterrupted series of public demonstrations in which the archbishop of Montreal, who presided over the event, shone in all his glory. With 25,000 young people in the Montreal Arena on Saturday afternoon, the memorable gathering in Notre-Dame church that same evening [see Bourassa], and 50,000 men participating in the final procession on Sunday, the congress was a success from beginning to end and the principal credit went to Bruchési. It was clearly the high point of his episcopate. It provided momentum for Eucharistic piety in the diocese, including a movement for frequent communion and the 1915 Congrès National des Prêtres-Adorateurs du Canada. One can imagine that after this public and religious triumph the archbishop might have had high hopes of receiving a cardinal’s hat. In the end, the title of cardinal went to his colleague in Quebec City, Archbishop Bégin, in 1914, on the eve of World War I. And this disappointment was not the only one Bruchési would experience during the decade beginning in 1911.

The second period of his episcopate began with the illness of his auxiliary, Bishop Racicot, who had to be replaced. Canon Georges Gauthier, the curé of the cathedral, whom Bruchési had strongly backed for the see of Ottawa in 1910, was chosen for the office and consecrated on 24 Aug. 1912. A question of great complexity concerning the Collège Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir now arose. In 1907 a fire had destroyed the college at Marieville in the diocese of Saint-Hyacinthe. The priests at the college wanted to relocate it to Saint-Jean (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu), which was on the border of the diocese of Montreal. Bruchési was prepared to let them come, but their bishop, Alexis-Xyste Bernard, refused to agree to the move. The dispute was referred to Rome, which in 1908 confirmed Bernard’s right to deny the request. All the same, the priests opened a college in Saint-Jean in 1909. Bruchési put a great deal of effort into the matter, which he hoped to resolve. After participating in the International Eucharistic Congress in Madrid in 1911, he went to Rome. From there he ordered that another college be opened in Saint-Jean under the direction of Abbé Joseph-Arthur Papineau*, the future bishop of Joliette. But the populace remained loyal to the priests of the old Collège Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir, who on 13 May 1912 were placed under suspension a divinis, a decree from Rome forbidding them to celebrate the mass or other sacraments. The crisis then became acute. Interdicted by Bruchési, the priests eventually had to close their college. Several of them – professors and students – then went to the Collège Nominingue, run by the Canons Regular of the Immaculate Conception.

On the national scene, the Ontario schools question and Regulation 17 [see Sir James Pliny Whitney*] occupied centre stage. Against this backdrop, in 1913 the new president of the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal, Olivar Asselin, organized a fund-raising campaign, the Sou de la Pensée Française, instead of the 24th of June parade. The cancellation of the procession aroused a great deal of opposition. On 26 July, in the city’s newspaper L’Action [see Jules Fournier*], Asselin made a spirited attack on the lamb of St John, which had become “the symbol of passive and stupid submission to every tyranny.” Bruchési’s protest prompted the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal to pass a motion of censure against its president, who eventually tendered his resignation in June 1914.

In addition to the matter of Regulation 17, in which Bruchési was not on the same wavelength as Asselin and other nationalist leaders, was the equally sensitive issue of Canada’s participation in World War I. Bruchési’s loyalty was evident from the outbreak of the conflict. On 14 Sept. 1914 he declared: “England is at war.… As loyal subjects …, we owe her our most generous support.” He obtained from the episcopate a collective pastoral letter, signed on 23 September, backing the war policy. The nationalist movement, with Bourassa at the forefront, would quickly become outraged. Asselin had no qualms about dragging Bruchési before the court of public opinion in his rising flood of articles and pamphlets. The question of the Ontario schools and that of the war now became inextricably intertwined: people talked about Ontario’s Boche as well as its wounded and its Prussians [see Samuel McCallum Genest]. In 1915 Bruchési was called in as a conciliator by Charles Hugh Gauthier*, the archbishop of Ottawa, but he was unsuccessful. Although he indisputably supported the cause of French Canadians in Ontario and French-language rights, his moderate positions did not strike a chord with the nationalist Franco-Ontarian leaders.

Bruchési reached his nadir during the conscription crisis of 1917. At the request of Prime Minister Sir Robert Laird Borden, in January he supported (as did Cardinal Bégin) the distribution of the National Service Board’s questionnaire [see Richard Bedford Bennett*], on the basis of the government’s promise that there would be no conscription. When conscription was announced in May [see Bourassa] and then introduced in August after the Military Service Act received royal assent, the archbishop lost face and was bitterly disappointed. On 27 May he had written to Borden, strongly advising him to abandon the plan for conscription, which he considered “ill timed and regrettable.” While he and Cardinal Bégin succeeded in obtaining an exemption for the clergy, he nevertheless considered conscription “a disastrous law” (according to his letter of 31 August to Borden). Various people, including his nephew Jean Bruchési and his eventual successor Bishop Georges Gauthier, believed that these events and the anguish they caused him led to the illness that struck the archbishop three years later.

On one question, however, the archbishop stayed the course: education. The controversial issue of compulsory education came up again in the Legislative Assembly in 1912 and then in 1918 and 1919. Each time, the archbishops of the dioceses of Quebec and Montreal, together with Premier Gouin, succeeded in keeping the movement in check. After Bruchési in 1913 forbade Catholics to read Le Pays, he even succeeded in having Langlois sent away to Brussels the next year as the province’s commercial representative. More important, the École des Hautes Études Commerciales was affiliated to the Montreal branch of the Université Laval in 1915 [see Jean Prévost*]. Finally, and above all, after a strenuous working stay in Rome from February to April 1919, he managed to obtain independence for the Montreal campus on 8 May. There was great rejoicing in the metropolis. On 22 November, however, the university burned down. This catastrophe led to a great fund-raising campaign and to the re-establishment of the institution in 1920 under the leadership of Bishop Georges Gauthier, the rector of the new Université de Montréal.

The archbishop’s involvement in public issues did not prevent him from fostering many good works, which formed another important part of his ministry. In religious matters Bruchési closely followed the development of St Joseph’s Oratory by Brother André [Alfred Bessette]. He also strongly supported hospital institutions: the Hôpital du Sacré-Cœur (later, in 1902, the Hôpital des Incurables), which was entrusted to the Sisters of Charity of Providence in 1899; the Hôpital Sainte-Justine for children, created in 1907 by Justine Beaubien, Irma Le Vasseur*, and other women; and the Institut Bruchési founded in 1911 to combat tuberculosis. In 1914 and 1915, he wholeheartedly encouraged the establishment of conferences of the St Vincent de Paul Society in the parishes to provide for the needs of the poor. In 1913 he promoted the movement for closed retreats. At the social level, in 1920 he took part in the first gathering of the Semaines Sociales du Canada at which the question of organizing Catholic trade unions [see Joseph-Papin Archambault*; Gaudiose Hébert*] was raised.

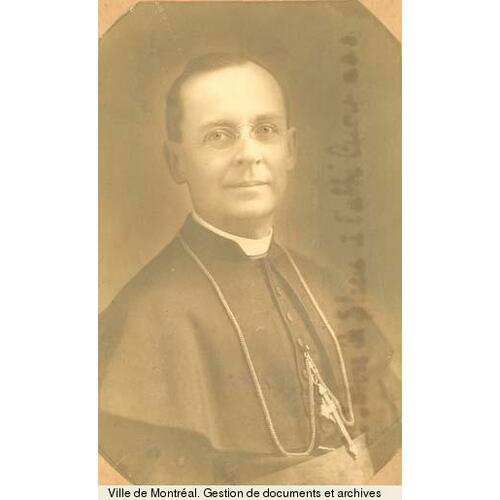

But all this activity had exhausted him. In October 1919 Bruchési was admitted to the Hôtel-Dieu hospital in Montreal. His illness could not be identified. There was no improvement in his condition in 1920 and it deteriorated rapidly in 1921. As a result, Bishop Gauthier was named apostolic administrator on 18 Oct. 1921 and coadjutor with right of succession on 15 April 1923. Bruchési had not lost his memory or his mind, but he was unable to make any decisions. He would remain confined to his room in the archbishop’s palace for 18 years. “What is happening in me is very mysterious,” he wrote on 23 Sept. 1937 to his nephew Jean. He then took a turn for the better, composed many letters, and even made a few visits by automobile. He died on 20 Sept. 1939 at the age of 83.

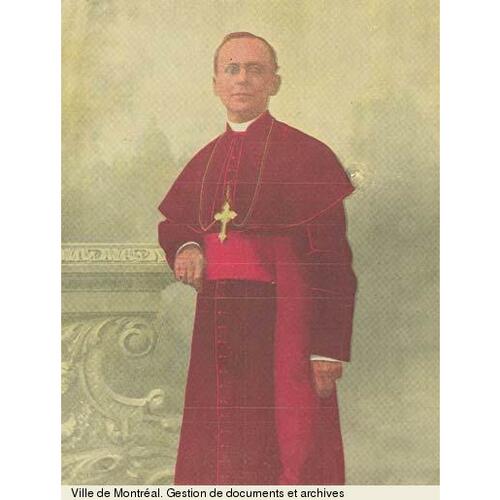

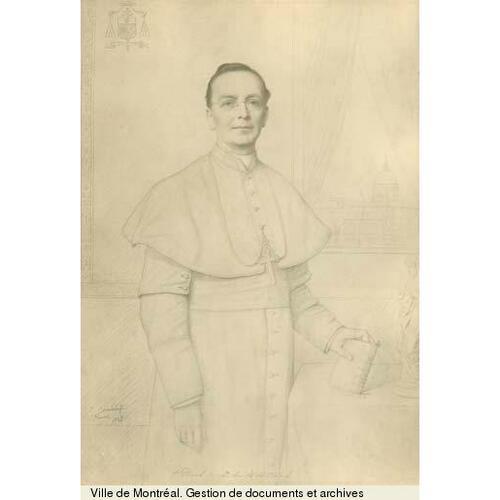

How can one characterize this man? He was certainly appreciated by most of his contemporaries, apart from the radical liberals and freethinkers. Éva Côté [Circé*] used these words to describe him in Le Pays on 4 Aug. 1917: “His mind was not of such a great depth that in casting the lead one could not touch bottom, but it was of such a subtle quality that it could no more be grasped than a ray of light. Delicate as a shadow, penetrating as a subterranean stream, he succeeded through intrigue where others, with strength of head and heart, would have failed. Not a scholar, but deliciously superficial.” In 1919 Laurent-Olivier David*, a Liberal of the Laurier stripe, wrote his biography and portrayed him thus: “He was not tall in stature. But a straight, elegant body, with a handsome head, regular features, [and] a very expressive face, gave him an attractive exterior.” The moral description that follows is very flattering and gives a full account of many traits of the archbishop’s personality: inspired improvising, friendships, kindness, love of the church and loyalty to principles, patriotism, concern for workers, and attachment to people.

The historian of the 21st century may render a more nuanced judgement, situated somewhere between the praises of Paul Bruchési’s contemporaries and a certain scorn on the part of the scholar’s own contemporaries, probably due to the image of a prelate identified with various interdictions that proliferated between 1900 and 1914 and to his subservient loyalty during the war. The multitude of tasks that this man had to accomplish every day is unimaginable. One has only to skim through his correspondence – it is doubtful that anyone has ever read it in its entirety – to appreciate the many dimensions of his office. He was first a Montrealer, but even more, he was a Catholic priest. He had great influence at the beginning of his episcopate, intervening brilliantly in the most complicated public matters and radically changing the climate of the church–state relationship. Bruchési stood for harmonious relations with the government representatives of the day. After the triumph of the International Eucharistic Congress, which enabled him to present in the best light his notion of publicly affirmed Catholicism, he experienced many difficulties in the second decade of the century, which led to the illness that interrupted his career at about the age of 65. Nevertheless, he remains, all in all, after Bishop Ignace Bourget and Cardinal Paul-Émile Léger*, one of the most outstanding bishops to have led the diocese of Montreal.

The most important sources for the study of Mgr Paul Bruchési’s active administration are his fonds at the Arch. de la Chancellerie de l’Archevêché de Montréal (901.165-901.186) and the reg. of his letters (RLBr, T-1-T-8), approximately 495 pages each (1897–1921). The Fonds Jean Bruchési (P57, 1009–1148), at the Div. des arch., Univ. de Montréal, contains many letters he exchanged with members of his family, friends, and religious communities (1872–1938). Jean Bruchési, nephew of the archbishop, collected much material for publications about his uncle, including a project to issue his correspondence in three volumes; he wrote an introduction, “Un inlassable épistolier: Paul-Napoléon Bruchési (1855–1939),” RSC, Trans., 4th ser., 10 (1972), sect.i: 115–26. In the fonds, of particular note is Bruchési’s correspondence with his spiritual adviser, Clément-François Palin d’Abonville, from 1869 to 1896 (1009–1010).

Among the printed sources, the most important are vols. 13 to 16 of Mandements, lettres pastorales, circulaires et autres documents publiés dans le diocèse de Montréal depuis son érection (30v., Montréal, 1887–1962), which contain the enactments that the archbishop wanted to be remembered by history. La Semaine religieuse de Montréal, from 1883 to 1939, which Bruchési edited from 1887 to 1897, is also useful. Some of Bruchési’s sermons, lectures, and speeches were published and lists can be found in library catalogues. As well, Bruchési published a small book under the pseudonym of Louis des Lys, Vœux de bonne année (Québec, 1883). Consultation of the following two print sources was also helpful: [Gaspard Dauth et J.‑A.‑S. Perron], Le diocèse de Montréal à la fin du dix-neuvième siècle … (Montréal, 1900) and XXIe Congrès eucharistique international, Montréal (Montréal, 1911).

Bruchési’s career as a priest is well summed up in “Mgr Paul Bruchési: notes biographiques,” La Semaine religieuse de Montréal, 3 juill. 1897: 3–16. A portrait by a liberal contemporary was published in La Presse, 13 déc. 1919, and reprinted in L.‑O. David, Mgr Paul Bruchési … (Montréal, 1926), 11–40. The most interesting obituary is by É.‑J.[‑A.] Auclair, “Mgr l’archevêque Bruchési,” Le Canada ecclésiastique … (Montréal), 1940: 57–64. The assessment of Bruchési in LeBlanc, DBECC, gives many other references. There is also an article by his great-nephew, Claude Bruchési, “Monseigneur Paul Bruchési (1855–1939), 2e archevêque de Montréal (1897–1939),” Mon collège: périodique des anciens du collège de Montréal (Montréal), 42, no.4 (1990): 1–12; 43, no.1 (1991): 2–3. The articles by Jean Bruchési rely mainly on his uncle’s correspondence: “La vocation sulpicienne de Monseigneur Bruchési,” RSC, Trans., 3rd ser., 35 (1941), sect.i: 23–35; “Un ecclésiastique canadien à Rome (1876–1879) …,” CCHA, Rapport, 18 (1950–51): 13–14; “L’abbé Paul-Napoléon Bruchési à Québec (1880–1884),” Cahiers des Dix, 21 (1956): 137–57; “Un voyage en Europe (1888–89),” RSC, Trans., 3rd ser., 38 (1944), sect.i: 37–48; “Brève histoire d’une longue amitié,” Cahiers des Dix, 23 (1958): 217–40, about the friendship between Thomas Chapais and Bruchési; “Sir Wilfrid Laurier et Monseigneur Bruchési,” RSC, Trans., 3rd ser., 40 (1946), sect.i: 3–22; “Mgr Bruchési et quelques communautés religieuses de son diocèse,” CCHA, Rapport, 14 (1946–47): 25–46; “Service national et conscription, 1914–1917,” RSC, Trans., 3rd ser., 44 (1950), sect.i: 1–18. Four of these articles were included in his Témoignages d’hier: essais (Montréal et Paris, 1961), 203–301. The reader may also refer to Séraphin Marion, “Mgr Bruchési, Mgr Rozier et la Troisième République,” CCHA, Rapport, 18 (1950–51): 15–24 and Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vols. 6–26 (especially vol. 15, entitled Mgr Bruchési).

Among the authors who have studied Bruchési more recently are: Michèle Dagenais, “Vie culturelle et pouvoirs publics locaux: la fondation de la bibliothèque municipale de Montréal,” Urban Hist. Rev. (Toronto), 24 (1995–96), no.2: 40–56; René Durocher, “Henri Bourassa, les évêques et la guerre de 1914–1918,” CHA, Hist. Papers, 1971: 248–75; P. [A.] Dutil, Devil’s advocate: Godfroy Langlois and the politics of Liberal progressivism in Laurier’s Quebec, trans. Madeleine Hébert (Montreal, 1995); Geoffrey Ewen, “Montréal Catholic school teachers, international unions, and Archbishop Bruchési: the Association de Bien-Être des Instituteurs et Institutrices de Montréal, 1919–20,” Hist. Studies in Education (London, Ont.), 12 (2000): 54–72; Ramon Hathorn, “Sarah Bernhardt and the bishops of Montreal and Quebec,” CCHA, Hist. Studies, 53 (1986): 97–120; Ruby Heap, “La Ligue de l’enseignement (1902–1904): héritage du passé et nouveaux défis,” RHAF, 36 (1982–83): 339–73; Histoire du catholicisme québécois, sous la dir. de Nive Voisine (2 tomes en 4v. parus, Montréal, 1984– ), tome 3, vol.1 (Jean Hamelin et Nicole Gagnon, Le xxe siècle (1898–1940), 1984); Claire Latraverse, “Rituel religieux et mesure politique au Congrès eucharistique de Montréal en 1910,” Bull. d’hist. politique (Montréal), 14 (2005–6), no.1: 119–31; Francis Primeau, “Le libéralisme dans la pensée religieuse de Mgr Bruchési,” Mens (Montréal), 7 (2006–7): 241–77. Three masters’ theses deserve to be consulted: Francis Primeau, “Mgr Bruchési et la modernité à Montréal: étude du rapport entre la religion et la modernité au début du XXe siècle (1897–1914)” (univ. de Montréal, 2005); Lise Saint-Jacques, “Mgr Bruchési et le contrôle des paroles divergentes: journalisme, polémiques et censure (1896–1910)” (univ. du Québec à Montréal, 1987); Donald Tremblay, “Monseigneur Paul Bruchesi and the conscription crisis of the First World War in French Canada” (Catholic Univ. of America, Washington, 1988).

BANQ-CAM, CE601-S51, 29 oct. 1855. Le Devoir, 21, 22, 25 sept. 1939.

Cite This Article

Guy Laperrière, “BRUCHÉSI, PAUL (baptized Louis-Joseph-Paul-Napoléon) (Napoléon),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bruchesi_paul_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bruchesi_paul_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Guy Laperrière |

| Title of Article: | BRUCHÉSI, PAUL (baptized Louis-Joseph-Paul-Napoléon) (Napoléon) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2017 |

| Year of revision: | 2017 |

| Access Date: | March 2, 2026 |