Source: Link

ODLUM, EDWARD, militiaman, educator, geologist, ethnologist, businessman, lecturer, politician, and lay preacher; b. 27 Nov. 1850 in Tullamore, Upper Canada, son of John Abraham Odlum and Margaret Mackenzie; m. first 3 July 1878 Mary Elvira Powell (d. 1888) in Cobourg, Ont., and they had four sons, of whom the second was Victor Wentworth Odlum* and the third and fourth predeceased him; m. secondly 12 April 1905 Martha Matilda Thomas in Toronto, and they had two sons, of whom one predeceased him; d. 4 May 1935 in Vancouver.

At the age of 15, Edward Odlum served with the 36th (Peel) Battalion when the militia was called out to counter the Fenian threat to Canada, and he was always proud of this episode, as he was of his English and Irish heritage. After completing his secondary studies in Goderich, Odlum attended Victoria College in Cobourg, graduating with a ba (1879) and an ma (1883). He taught at Cobourg Collegiate before being appointed principal of the high school in Pembroke.

In 1886 Odlum, with his family, went out to Japan as a member of the Self-Support Band founded by fellow Methodist Charles Samuel Eby*. There Odlum became a teacher at Tōyō Eiwa Gakkō [see George Cochran*], the church’s school for the training of Japanese clergy, and assumed the title of professor, which he would use for the rest of his life even though his employment at the institution seems to have been his only academic post. While in Japan he also pursued geology, which he had become interested in when prospecting in Ontario during his student days. His scientific accomplishments, including a published study of the effects of the 1888 eruption of Mount Bandai, were considerable for his time and would help him earn a bsc from Victoria College in 1892.

Following his wife’s death from malaria and pneumonia, Odlum left Japan and travelled through Australia, New Zealand, and the United States before settling in Vancouver in 1889. He would live there for the rest of his life, except for two stints in the late 1890s: he briefly managed a gold mine in the Cariboo region of British Columbia, and he toured Great Britain on behalf of the federal and British Columbia governments, promoting immigration to Canada. The latter role seems to have suited Odlum, whose optimism about his country’s future and devotion to the British connection are evident in an 1896 pamphlet in which he asserts that “there is room in Canada for 200,000,000 people,” and stresses the bonds between Canadians and Britons:

Appreciating our great heritage, we invite our kith and kin from across the water to join us in building up a grand and powerful nation – a bulwark in the future against anarchy and a tower of strength in favour of liberty, order, and progress. Your flag is our flag, your spirit our spirit, your Bible our Bible, your empire our empire, your destiny our destiny, your Queen our Queen, and your God our God.

In Vancouver, which was in the midst of a real-estate boom when he first settled there, Odlum made a successful living selling insurance and real estate. (He coined the name of his own east-end neighbourhood, Grandview.) He also became involved in politics, serving two terms on city council (1892, 1904) and standing unsuccessfully for the provincial legislature (1894) and the local mayor’s office (1909). He expounded his populist views in the Western Call, a muckraking newspaper published by Henry Herbert Stevens*, and other serials. Odlum championed various causes, including temperance legislation, a civil service free of political interference, restrictions on Chinese immigration, and public ownership of key industries such as coal mining. In 1908 he presided over a board that arbitrated a dispute between Sir Thomas George Shaughnessy*’s Canadian Pacific Railway and the Brotherhood of Railway Carmen. The board ruled in favour of the carmen, instituting a nine-hour workday and awarding a slight pay raise.

Christianity was fundamental to Odlum’s populism, and he remained an active Methodist: he served as assistant secretary to the provincial conference, sat on the board of management of Columbian Methodist College in New Westminster, and acted as a lay preacher. He was also worshipful master of Imperial Loyal Orange Lodge No.1815 in Vancouver, and he spoke regularly at Orange gatherings. His religious commitments did not preclude scholarly pursuits. As president of the Art, Historical and Scientific Association of Vancouver, he was consulted about palaeontological finds along the west coast, and he used his column in the Western Call to publicize his geological research into the cause of the infamous rockslide that struck Frank, Alta, in 1903. Drawing on his recollections of an 1895 tour of the British Columbia coast that he had taken with Methodist missionary Thomas Crosby*, Odlum also published a number of ethnographic articles on the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific northwest.

The reconciliation of science and religion became a great preoccupation for Odlum. At Victoria College he had known Nathanael Burwash*, a proponent of such a reconciliation, and their acquaintance lasted for decades. (Burwash performed both of Odlum’s marriages.) Unlike Burwash, however, Odlum rejected biblical higher criticism and embraced what he described as theistic science, whereby the natural sciences were commandeered to confirm the literal veracity of Scripture. His religious, geological, and ethnographic interests converged in his embrace of British Israelism [see Joseph Wild*], the belief that the peoples of the British Isles are descendants of the lost tribes of Israel. Odlum published two compendia of British Israelite lore, God’s covenant man: British-Israel (1916) and Great Britain great (1921), and lectured extensively on the subject throughout Canada and Great Britain. In 1917 he founded the Vancouver British Israel Association, which in 1921 became the British Israel Association of Canada. Odlum helped organize a national federation of similar bodies, and eventually the name British Israel Association of Greater Vancouver was adopted. In 1921, while attending a convention of the British-Israel-World Federation in London, Odlum analysed the Stone of Scone at Westminster Abbey, his access having been facilitated by the Canadian high commissioner, Sir George Halsey Perley*. Travelling in Palestine some months later, Odlum allegedly found deposits of similar stone in the vicinity of Bethel (Beitin, Jordan), which he believed confirmed the biblical lineage of the British royal family. He also hypothesized that earthquakes in the Holy Land would portend the coming of Armageddon.

Odlum’s ethnological contribution to British Israelite thought was his most creative. Based on observations made during his sojourn in Japan, he speculated that the Japanese were one of the lost Israelite tribes and therefore ethnic kin to peoples of British decent. His views had political implications: in a provocative 1927 lecture, Odlum objected to legal restrictions imposed on Canadians of Japanese origin. He contended that “the ruling people of Japan are as truly Semitic as you and I, as truly Saxon as you and I are … and God will not permit Canada, either at Ottawa or Victoria to carry out an unjust law discriminating against people who have received citizenship in our land.” Odlum also suggested that the Indigenous peoples of the British Columbia coast were descended from Japanese travellers, and by extension from the ancient Israelites. In a lecture delivered around 1906, apparently to a white audience, he exhorted British Columbians, “Behold your brethren in loving amazement!”

Edward Odlum was well respected in Vancouver. When he died in 1935, the Vancouver Daily Province mourned a “theologian, scientist and educationist of international reputation,” and a meeting of the city council was postponed to allow the mayor to serve as an honorary pall-bearer at his funeral. Yet Odlum’s legacy is darker than he might have anticipated. Although his brand of British Israelism was inclusive for its day, his ambivalence towards Jews, whom he had long insisted were not the biblical people of Israel, turned into antagonism in his later correspondence. Following his death, the British Israel Association of Greater Vancouver became increasingly anti-Semitic and forged strong ties with extremist groups in the western United States, including the Ku Klux Klan. The theories of racial origins proposed by a new generation of British Israelites inspired the Christian Identity movement, whose adherents, still active in the early 21st century, claim that Jews are the children of Satan. Considering his benevolent (if paternalistic) attitude towards Indigenous peoples and the Japanese, Odlum might have been surprised to learn that he had laid the institutional foundation for a particularly virulent strain of white supremacist ideology.

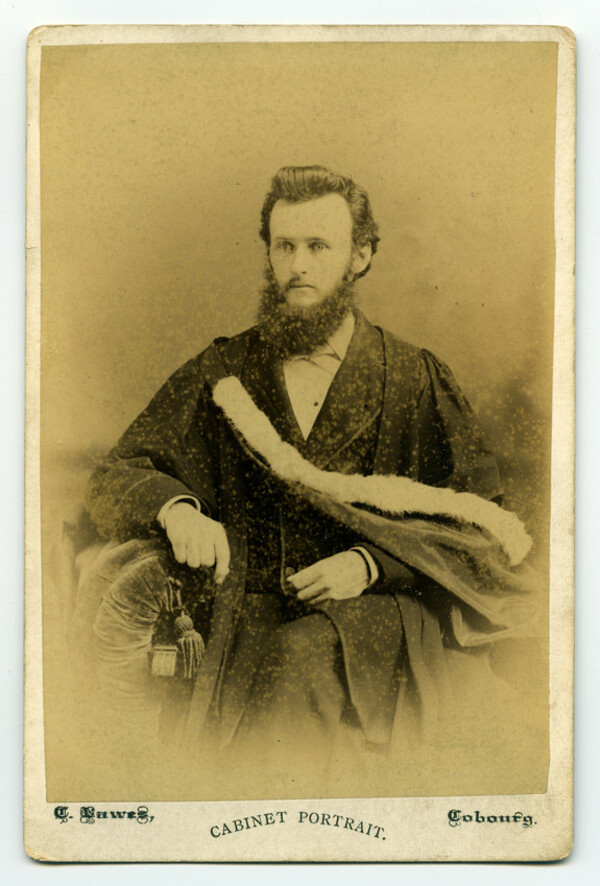

Edward Odlum was a prolific writer and public speaker, and his articles and speeches appear in various newspapers and journals of his era. His most important publications on British Israelism are God’s covenant man: British-Israel (London and Toronto, 1916) and Great Britain great (Vancouver, 1921). One of his lectures was published as Who are the Japanese? ([London?, 1932]), and the Univ. of B.C. Library, Rare Books and Special Coll. (Vancouver), RBSC-ARC-1414 (Odlum family fonds), box 2, holds copies of his lectures in file 6 (“The ethnological relationship of the ruling Japanese to the members of the British Columbia Legislature”) and file 9 (“Ebb and flow of humanity”). His geological publications include “The sand plains and changes of water-level of the Upper Ottawa,” Ottawa Field-Naturalists’ Club, Trans., no.5 (1883–84): 38–54; “How were the cone-shaped holes on Bandaisan formed?,” Seismological Soc. of Japan, Trans. (Yokohama, Japan), 13, pt.1 (1889): 21–40; and “Geologic and other changes in Palestine and Egypt,” Beacon (Vancouver), October 1926: 8–9. His ethnological descriptions of Indigenous peoples can be found in “The Tsimpseans of British Columbia and Klingets of Alaska,” Chautauquan (Meadville, Pa), 25 (April–September 1897): 627–31; “The Indians of the Pacific coast,” British Pacific (Cumberland, B.C.), June 1902: 11–22; and “The Klingets of Alaska,” British Pacific, July 1902: 64–74. Victoria Univ. in the Univ. of Toronto, Library & Arch., Digital Coll., holds a digitized 1879 photograph of Odlum at “E. Odlum, 1897”: digitalcollections.vicu.utoronto.ca/RS/?r=706 (consulted 11 Jan. 2018).

City of Vancouver Arch., AM190 (Edward Odlum fonds). LAC, R4925-0-5 (Victor Wentworth Odlum fonds). Univ. of B.C. Library, Rare Books and Special Coll., RBSC-ARC-1414 (Odlum family fonds). Abbotsford Post (Abbotsford, B.C.), 23 Feb. 1912. British Columbian (New Westminster, B.C.), 16 July 1912. Daily Colonist (Victoria), 19 July, 16 Nov. 1890; 15 Jan., 17 March, 12 May, 28 Aug. 1892; 10, 14 April 1896; 5 July 1899; 15 Jan., 24 July 1904; 20 April 1905; 26 March, 28 Aug., 3, 19 Dec. 1907; 15 Jan. 1909. Daily Mail and Empire, 6 May 1935. Ledge (New Denver, B.C.), 6 May 1897. Vancouver Daily Province, 6 May 1935. Western Call (Vancouver), 10, 17 Feb., 19 May, 18 Aug. 1911. Michael Barkun, Religion and the racist right: the origins of the Christian Identity movement (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1994). British Israel Assoc. of Greater Vancouver, Inc., Memorial historical statement ([Vancouver], 1935). Thomas Crosby, Up and down the North Pacific coast by canoe and mission ship (Toronto, 1914). R. E. Gosnell, A history o[f] British Columbia (n.p., 1906). A. H. Ion, “Canadian missionaries in Meiji Japan: the Japan Mission of the Methodist Church of Canada (1873–1889)” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1972). “Liste générale des géologues, minéralogistes et paléontologistes,” Annuaire géologique universel et guide du géologue autour de la terre … (Paris), 1886. G. R. P. Norman and Howard Norman, “One hundred years in Japan, 1873–1973” (2v., typescript, [Toronto], 1981), 1. Vancouver County Orange Lodges, Official special souvenir programme, Twelfth of July, 1913, Vancouver, B.C. ([Vancouver, 1913]).

Cite This Article

Forrest D. Pass, “ODLUM, EDWARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/odlum_edward_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/odlum_edward_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Forrest D. Pass |

| Title of Article: | ODLUM, EDWARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | January 19, 2026 |