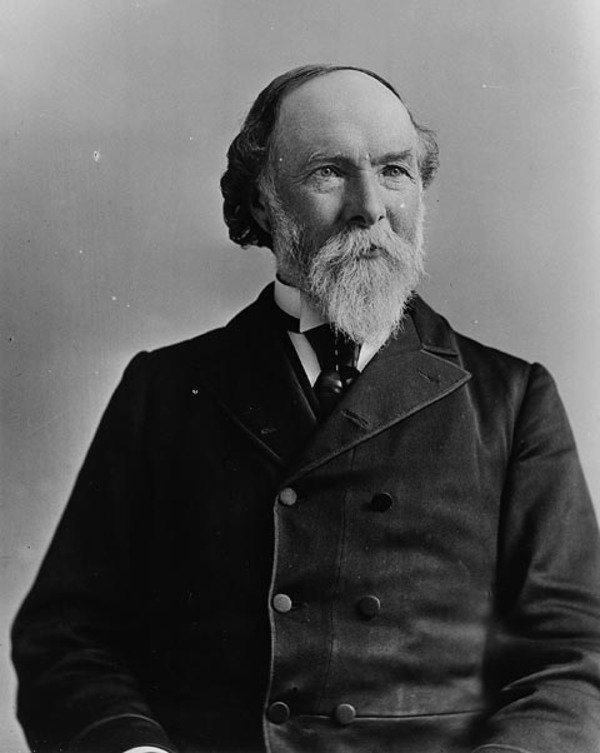

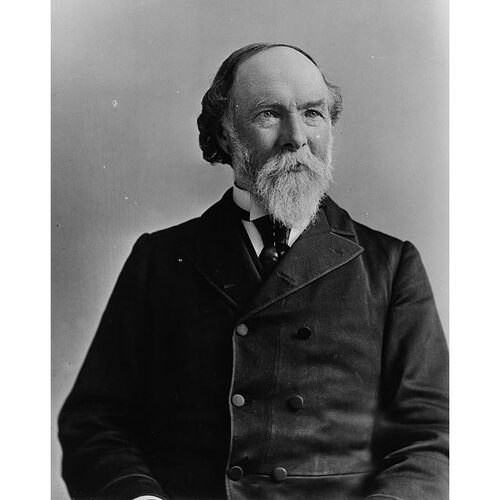

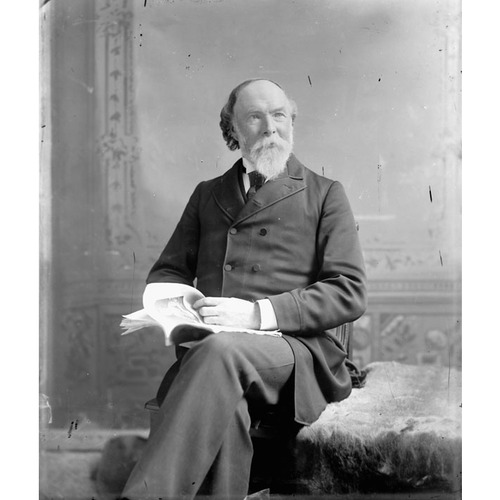

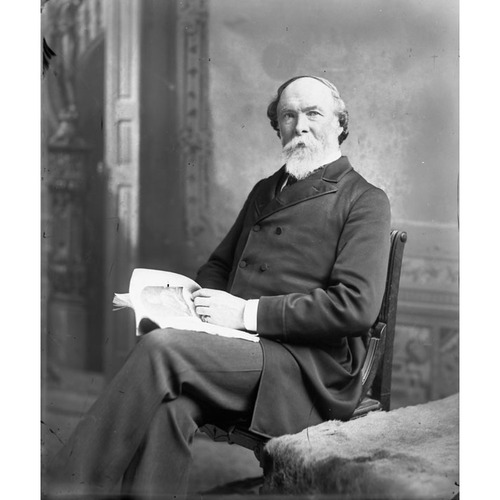

MACDONALD, ANDREW ARCHIBALD, merchant, politician, and office holder; b. 14 Feb. 1829 at Brudenell Point, P.E.I., eldest child of Hugh Macdonald and Catharine Macdonald; m. 25 Nov. 1863 Elizabeth Lee Owen* in Georgetown, P.E.I., and they had four sons; d. 21 March 1912 in Ottawa.

Andrew A. Macdonald is best seen as part of a family dynasty that dominated the political and economic life of central Kings County for over a century. His paternal grandfather, Andrew, a Highland tacksman and merchant, had emigrated to Prince Edward Island with about 40 kinsmen in 1806. He purchased 10,000 acres in lots 8 and 52, as well as Panmure Island, where he and his family settled. In partnership with his sons Angus and Hugh he established a mercantile and shipbuilding enterprise. By the time Andrew A. was born in 1829, his grandfather had retired and Hugh and Angus were carrying on the business. Leading Roman Catholics, they were among the first Catholic members elected to the Island’s House of Assembly in 1830.

Something of the Macdonalds’ Old World standing survived the passage to Prince Edward Island. Along with a handful of families, such as their cousins the MacDonalds of Tracadie [see John MacDonald* of Glenaladale], they formed a kind of Scots Catholic aristocracy in the little colony. Their relative affluence and proud bloodlines commanded deference – if not obedience – from other Catholic Highlanders; respect – if not deference – from a local church hierarchy that was itself dominated by Highland Scots; and entry into – though not always acceptance from – “respectable” Protestant society.

Macdonald’s early childhood was spent in a fine brick house, surrounded by servants. He was tutored privately, besides attending a rough-and-ready school in Georgetown, but a series of financial reverses for the family curtailed his formal education. In 1844, at age 15, he was sent to work at a store in Georgetown owned by a cousin. On his kinsman’s death in 1851 he succeeded to the business, and he soon took his two brothers, Archibald John and Augustine Colin, into partnership with him as A. A. Macdonald and Brothers. The firm developed an extensive and diverse business. Between 1850 and 1870 Andrew had a hand in the ownership of 20 vessels, some built for export, but the majority employed in the carrying trade. His company shipped grain, potatoes, and lumber to New England, Newfoundland, and Great Britain, and imported manufactured goods for sale in its stores at Georgetown and Montague Bridge (Montagu). During the 1860s and 1870s the firm also exploited the mackerel fishery in the Gulf of St Lawrence.

Trade – and family precedents – proved springboards into politics for Macdonald. In 1854 he captured a seat in the assembly for Georgetown and Royalty. His family’s landholding background had given it conservative leanings, but Macdonald followed traditional Island Catholic practice by supporting the liberals, who were returned to power under George Coles*. Although he spoke infrequently in the house, his concise style, reasoned arguments, and self-professed adherence to the desires of his constituents established patterns that would characterize his parliamentary career.

Macdonald was re-elected in 1858, and again the following year. His election in 1859 was protested by one of the defeated candidates, and after a controversial scrutiny in the conservative-dominated house, he was unseated. Defeated in the bitterly contested “no popery” election 1863 [see William Henry Pope*], he won a seat a few weeks later in the newly elective Legislative Council, only to be unseated once again. In the ensuing by-election, he was returned unopposed. This trial by fire seems to have toughened Macdonald, and in the legislative session of 1864 he emerged as opposition leader in the Legislative Council. When the liberals under Coles regained office in 1867, Macdonald was named to the Executive Council on 2 April 1867, and became government leader in the Legislative Council.

Macdonald’s political career spanned one of the most partisan eras in the Island’s history. During the critical decade between 1863 and 1873 its politics was dominated by four great questions: land, confederation, railways, and education. Taken separately, each would have challenged the most stable of governments. Tangled together as they were, they made a shambles of the colony’s fledgling party system.

As a merchant who stood to profit from the prosperity of small landholders, Macdonald was a natural supporter of land reform that would eliminate the colony’s leasehold system, but as a man of property he rejected the violent defiance of the Tenant League movement of the mid 1860s [see Edward Whelan*]. Macdonald favoured voluntary sale of proprietorial estates to the government. When a compulsory Land Purchase Act was passed in 1875 by the government of his brother-in-law Lemuel Cambridge Owen, he was appointed a public trustee to oversee the liquidation of the last of these estates.

No such moderation was possible with respect to the education question. All through the 1860s Peter McIntyre*, the Roman Catholic bishop of Charlottetown, had waged a campaign to win public support for sectarian schools. Macdonald managed to skirt the issue for a time but in the end his party allegiance crumbled beneath the pressures of his religious loyalties. In 1870, when the liberal caucus refused to support government endowment for Roman Catholic St Dunstan’s College, he and George William Howlan* led its Catholic members into an uneasy alliance with James Colledge Pope*’s conservatives, causing the resignation of Robert Poore Haythorne*’s government. The glue that held the new coalition together was a remarkable pledge not to tamper with either the confederation or the education question until the next general election. Although no longer government leader in the Legislative Council, Macdonald played a prominent role in the Pope administration. He was an enthusiastic supporter of its decision to construct a railway to span the colony, and his reputation weathered the storm of accusations about bribes and corruption in connection with the line that brought down the government in March 1872.

As nasty as the railway question became, it caused Macdonald far less trouble than the festering issue of denominational schools. By the early 1870s McIntyre was calling for a full-fledged separate school system funded from the public purse. The polarization of opinion left Macdonald in a difficult position. Although a devout Roman Catholic, he did not regard himself primarily as a “Catholic” politician. When he tried to maintain his political integrity while doing his duty as a Roman Catholic, he fell foul of the redoubtable bishop.

Having fallen on the railway-question, J. C. Pope’s supporters were freed from their pledge to shun the education question. In the summer of 1872 their caucus attempted to seduce the four Catholics in Haythorne’s new government by passing a resolution in favour of grants to denominational schools. Macdonald was part of the unofficial delegation that took the opposition’s offer to the bishop. When negotiations failed, the caucus withdrew its explicit proposal, but not the carrot of possible concessions.

As confederation with Canada neared, McIntyre increased the pressure on Roman Catholic politicians somehow to ram through legislation on separate schools. Macdonald and others offered in April 1873 to form an independent Catholic bloc in the legislature. Confident that he could still wring legislation out of the conservatives, the bishop urged them instead to help Pope, who was trying to form a government following his victory in the recent election held on the terms of union with Canada. They did, Macdonald, G. W. Howlan, and William Wilfred Sullivan joining the Executive Council. But when the “better terms” promised by Pope failed to include separate schools, McIntyre angrily demanded that all Catholic members turn on Pope’s government. Macdonald – and other Catholic tories – refused. He had already pledged himself to confederation and was not about to precipitate another political crisis. Enraged, the bishop allegedly accused Macdonald of “treachery and deception.” Stung by repeated attacks in the bishop’s organ, the Charlottetown Herald, Macdonald made a rare and somewhat reluctant defence of his conduct in a long letter to its editor.

Although it was the education question that gained Macdonald the greatest notoriety at the time, it is for his role in Prince Edward Island’s entry into confederation that he is today remembered. As opposition leader in the Legislative Council, he was named one of the five Island delegates to the Charlottetown conference in September 1864. When the talks resumed in Quebec City the following month, he was among the seven representatives sent from the Island, and his rough notes of the meeting constitute one of the major sources for reconstructing the give and take of the discussions. Besides his novel suggestion that each province should have equal representation in the proposed federal upper house, he played a relatively minor role.

At Charlottetown, Macdonald had flatly opposed the concept of legislative union. By the time the Quebec conference adjourned, he had made up his mind about federal union as well. Even were it accompanied by moneys to buy out the Island’s remaining leasehold estates, he argued, the doubly taxed little province would have little real power and few resources. In the years that followed he remained an avowed anti-confederate, convinced that the Island stood to gain nothing from union and that the vast majority of the inhabitants opposed it. Only the impending bankruptcy threatened in 1873 by the colony’s enormous railway debt converted Macdonald (as it did most other Islanders). Even then, he held out for terms that would allow the provincial government to carry on “without resorting to local taxation.” It was Haythorne’s liberal government that sought terms from Canada, but it was Pope’s conservative administration that led the Island into confederation. And it was Macdonald who moved the adoption of the final terms of union in the Legislative Council on 26 May 1873. Even before the colony’s official entry into confederation on 1 July 1873, Macdonald had left politics. In an effort to placate Catholics angered by his ambivalent educational policy, Pope appointed him postmaster general, a position that was converted at confederation into the federal postmastership of Charlottetown.

Around 1871 Macdonald had moved from Georgetown to Charlottetown. Withdrawing from A. A. Macdonald and Brothers, he opened a wholesale grocery business in Charlottetown in partnership with his brother-in-law A. Wallace Owen. But by 1878 Macdonald and Owen had failed, dealing Macdonald a heavy financial set-back. For the remainder of his life he would support himself largely through the salaries attached to his government appointments. He added honour to emolument when, on 1 Aug. 1884, he became lieutenant governor of the Island. His uneventful five-year term was distinguished chiefly by his imposition of strict temperance on Government House. On 11 May 1891 he was appointed to the Canadian Senate. His last years marred by ill health, he would die in Ottawa in 1912.

“What peculiar claims or wonderful service any member of that family ever did for the province or the Liberal Conservative party is hard to say,” wrote one of Macdonald’s rivals for public office in 1889, “but they are best known in King’s County as men who look to the interests of themselves.” The disparaging comment does Macdonald a disservice. For ten critical years he had been at the centre of Prince Edward Island affairs. If he attended to his self-interest, he always seemed to weigh it against his sense of honour and public duty, and in a bitterly partisan era he was widely respected for both his integrity and his ability. In later life he was regarded as something of a curiosity, the last but one (Sir Charles Tupper) of the Fathers of Confederation. The one-time anti-confederate died proud of his role as a founder of modern Canada.

As one of the last surviving Fathers of Confederation, Macdonald was in demand for his first-hand memories. His publications on the subject include “The confederation movement in Prince Edward Island,” in Canada, an encyclopædia (Hopkins), 5: 431–34; “Confederation by one of its makers,” Canadian Collier’s (Toronto), 43 (1909), no.15: 20–21; and, most important, “Notes on the Quebec conference, 1864,” ed. A. G. Doughty, CHR, 1 (1920): 26–47.

Macdonald’s diary for January–April 1870 was transcribed. by George Leard and published as “Ships and weather, by a Father of Confederation,” in Guardian of the Gulf (Charlottetown), 28–30 Jan. 1952.

NA, RG 42, 1352–71 (mfm. at PARO). PARO, Acc. 2323/6; Acc. 2654/224a; RG 5, minutes, 1867–73; Supreme Court, estates div. records, liber 19: f.60 (mfm.). Private arch., G. E. MacDonald (Charlottetown), A. J. Macdonald, untitled memoir, 1909 (photocopy). PRO, CO 226/106: 225–26 (mfm. at PARO). Examiner (Charlottetown), 16 Nov. 1857; 26 Jan., 9 Feb., 13 July 1863; 4 March 1872; 1 Aug. 1884. Haszard’s Gazette (Charlottetown), 24 June 1854. Herald (Charlottetown), 24 May 1871, 17 July 1901. Islander (Charlottetown), 11 Jan. 1856, continued as Prince Edward Islander, 28 Nov. 1873. Patriot (Charlottetown), 27 March 1869, 22 March 1912. Prince Edward Island Register (Charlottetown), 23 May 1826. Vindicator (Charlottetown), 2 Dec. 1863. J. M. Bumsted, “Parliamentary privilege and electoral disputes on colonial Prince Edward Island, part two,” Island Magazine (Charlottetown), no.27 (spring/summer 1990): 15–21. Canada’s smallest province: a history of P.E.I. ed. F. W. P. Bolger ([Charlottetown], 1973). CPG, 1891. [Archibald Irwin], “Our prominent men – xii: Hon. A. A. Macdonald,” Prince Edward Island Magazine and Educational Outlook (Charlottetown), 6 (1904): 25–30. Past and present of Prince Edward Island . . . , ed. D. A. MacKinnon and A. B. Warburton (Charlottetown, [1906]), 570–72. P.E.I., House of Assembly, Debates and proc., 1856–59; Journal, 1859, app.A; Legislative Council, Debates and proc., 1863–73; Journal, 1863–73. I. R. Robertson, “Religion, politics, and education in Prince Edward Island from 1856 to 1877” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1968).

Cite This Article

G. Edward MacDonald, “MACDONALD, ANDREW ARCHIBALD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 16, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_andrew_archibald_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_andrew_archibald_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | G. Edward MacDonald |

| Title of Article: | MACDONALD, ANDREW ARCHIBALD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | February 16, 2026 |