Source: Link

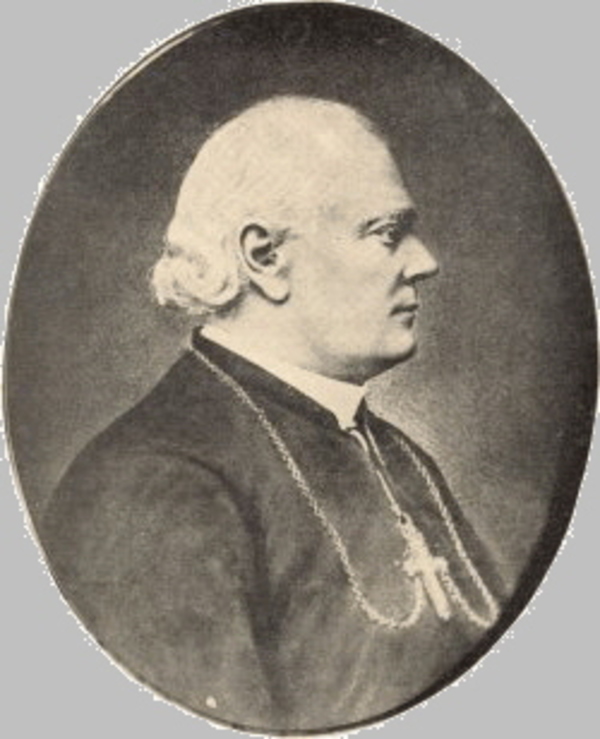

McINTYRE, PETER, Roman Catholic priest and bishop; b. 29 June 1818 in Cable Head, P.E.I., son of Angus McIntyre and Sarah MacKinnon, both of either North or South Uist, Scotland; d. 30 April 1891 in Antigonish, N.S.

The youngest of eight children, Peter McIntyre was early marked for the church. His parents had come to St John’s (Prince Edward) Island in 1790 as part of a large emigration from Highland Scotland. Father (later Bishop) Angus Bernard MacEachern* was a fellow traveller, and after Angus McIntyre settled at Cable Head on the Island’s north shore MacEachern habitually conducted services at his home. According to Peter McIntyre, his father was always in “fair circumstances”; local tradition avers that he owned a small trading vessel.

Young Peter became a protégé of MacEachern and, at the bishop’s insistence, he was educated with an eye to the seminary, first in a primitive country school at McAskill River and then in the diocesan college, St Andrew’s, established in 1831. After MacEachern’s death in 1835, McIntyre entered the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe in Lower Canada. From there he proceeded to the Collège de Chambly and in September 1840 he advanced to the Grand Séminaire de Québec for his sacerdotal training. On 26 Feb. 1843 he was ordained there by Bishop Pierre-Flavien Turgeon*.

That summer, McIntyre returned to the priest-poor diocese of Charlottetown, where Bishop Bernard Donald Macdonald* appointed him assistant to Father Sylvain-Éphrem Perrey* at Miscouche with responsibility for western Prince County. In the fall of 1844 he was appointed to the mission of Tignish, on the Island’s northwestern tip. During the next 16 years he built a reputation there as the diocese’s leading pastor.

Western Prince Edward Island had been settled much later than the bulk of the colony, and its inhabitants, mostly Roman Catholic Acadians and Irish, were correspondingly poor. McIntyre appears to have dominated them. Forceful and stubborn, fluent in both English and French and possessed of tremendous energy, he demonstrated a talent for organization and administration. His pastorate was capped by the construction, under his close supervision, of a new parish church for Tignish in 1859–60. St Simon and St Jude’s Church was characteristic of the man: in a colony of wooden buildings, McIntyre built in brick.

In 1857 McIntyre had represented the ailing Bishop Macdonald in negotiations in Montreal with the sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, which resulted in four of them establishing a convent in Charlottetown in September. By the time Macdonald died, on 30 Dec. 1859, McIntyre had become his logical successor. He was appointed bishop of Charlottetown on 8 May 1860, and on 15 August he was consecrated by Archbishop Thomas Louis Connolly* in St Dunstan’s Cathedral, Charlottetown, together with James Rogers*, bishop of the newly created diocese of Chatham, N.B.

McIntyre inherited a growing diocese badly in need of priests. Part of a colonial society increasingly split along denominational lines, the diocese had to operate within a political environment in which the promotion of religious bigotry had become an avenue to elected office. The 1861 census counted 35,852 Roman Catholic Islanders, comprising roughly 45 per cent of the total population. To minister to them there were only 14 priests. As it became better established, the Catholic population had grown increasingly aggressive about its rights and status. This posture, coupled with distant echoes of the Oxford Movement in Great Britain, fuelled Island Protestants’ fears of “papal aggression.” In 1856 controversy over the issue of Bible reading in the colony’s public school system had touched off an era of bitter political and religious discord. Fearing moral coercion of Catholic children, Bishop Macdonald had opposed the introduction of compulsory Bible reading into the Island’s denominationally mixed public school system. The opposition conservatives, under Edward Palmer*, had taken advantage of the inflammatory issue to unseat the ruling liberal government of George Coles* in the election of 1859 by campaigning on an anti-popery platform. Although the conservatives brought about a compromise solution to the Bible question in 1860 (Bible reading without comment was authorized during school hours for only those children whose parents requested it), the stage had been set for continuing controversy. It would persist through much of McIntyre’s episcopate.

The new bishop was the antithesis of his diffident predecessor. In many ways he personified his diocesans’ aspirations, for he was anxious to place Island Catholics on an equal footing, socially, politically, and economically, with their Protestant neighbours. Though perhaps a humble man, McIntyre proved a wilful and sometimes headstrong prelate. He ruled the diocese with an iron hand, brooking no opposition. In a sermon delivered following McIntyre’s death, a former protégé, Archbishop Cornelius O’Brien* of Halifax, would compare him to the stern biblical patriarch Nehemiah. Certainly, he was a stickler for protocol, jealous of his prerogatives, and fond of ceremony. He was also used to having his own way. Writing to Bishop Rogers in February 1890 near the end of his life, McIntyre declared, “I have faith in the sage principle that man must be, in a manner, his own providence, and provide against all contingencies under the unerring hand of the Almighty.”

In ecclesiastical matters McIntyre was a vigorous ultramontane. He went five times to Rome – in 1862, 1869–70, 1876–77, 1880, and 1889. At the first Vatican Council, in 1869–70, he broke with his own archbishop, Connolly, to endorse immediate promulgation of the controversial dogma of papal infallibility. This ultramontanism clearly tempered all aspects of McIntyre’s episcopal administration.

The diocese of Charlottetown prospered under McIntyre’s energetic leadership. Himself a proud Scot, McIntyre seems to have got on well with the Irish and Acadian components of his flock. He continued his predecessors’ practice of soliciting missionaries from the archdiocese of Quebec to serve the Acadians on Prince Edward Island and the Îles de la Madeleine, and he continued to send the diocese’s Scots, Irish, and Acadian candidates for the priesthood to Quebec to complete their ecclesiastical training. During his episcopate 58 priests were ordained for or employed in the diocese; by 1891 more than 30 priests were labouring there. At his urging, a union of Catholic total abstinence societies was organized throughout the diocese in 1877, and in 1888 he established the League of the Cross, another abstinence organization.

It fell to McIntyre to oversee the construction of ecclesiastical buildings commensurate with a larger, more settled, and more affluent Catholic community than his predecessors had known. He found the task to his liking. Along with 25 new churches, 21 presbyteries and 8 convents were built; a number of them were designed by the Island’s William Critchlow Harris*. In 1862 he had the rotting walls of the diocesan college, St Dunstan’s, rebuilt in brick; in 1875 he constructed a stone episcopal “palace” in Charlottetown; and in 1879 he converted his former residence into a 14-bed hospital, Charlottetown’s first, which was enlarged in 1882, eight years before work on a new building was begun. At his death, the bishop was busy with plans for a new stone cathedral.

In staffing these institutions McIntyre showed himself a skilled and determined negotiator. Besides the Congregation of Notre-Dame, primarily a teaching order, he persuaded both the Christian Brothers and the Sisters of Charity of the Hôpital Général of Montreal (Grey Nuns) to establish themselves in the diocese: the former came in 1870 to run a Catholic boys’ school in Charlottetown, the latter in 1879 to operate the new hospital. But he was not always able to hold those who came. In 1880 he prevailed on a reluctant Society of Jesus to assume control of St Dunstan’s College for a term of five years. Over McIntyre’s angry protests the Jesuits withdrew after only one year, disillusioned with conditions and prospects at the college.

The cost of McIntyre’s ambitious projects was in part defrayed by funds he solicited from the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, based in Lyons, France. Nevertheless, the diocese’s resources were stretched perilously thin. This chronic shortage of funds, along with his convictions about education, led McIntyre to the public purse and into bitter conflict with the Island’s Protestant majority.

Education was indeed one of McIntyre’s abiding interests. He established half a dozen schools and enthusiastically presided over end-of-year ceremonies. Moreover, he took so strong an interest in St Dunstan’s College that he became more closely identified with it than its founder, Bishop Macdonald. It was McIntyre who insisted on the college’s continuance when financial and administrative woes threatened to close it in 1884. He was convinced that religion and education not only could but must mix, and the first 17 years of his episcopate were largely spent in a vain attempt to force successive Island governments to subsidize the ad hoc Catholic school system he gradually created during the 1860s and 1870s.

The political merry-go-round had begun for McIntyre in 1861 when he engaged in private talks with Edward Palmer’s conservative government, which had won election in 1859 by promoting anti-Catholic feeling among Protestant voters but was now attempting to conciliate Island Catholics. At issue was McIntyre’s wish to secure an annual government grant to St Dunstan’s College. Negotiations with the Island’s colonial secretary, William Henry Pope*, collapsed and later became the subject of bitter recriminations in local newspapers. McIntyre did not personally participate in the exchange of polemics but engaged as his mouthpiece Father Angus McDonald*, rector of St Dunstan’s, who acted as Catholic champion in a series of inflammatory epistolary confrontations with various Protestant writers, including Pope and David Laird*. To strengthen the Catholic voice McIntyre established in Charlottetown in October 1862 the Vindicator, a militant Catholic newspaper published by Edward Reilly* and allegedly edited by McDonald. By the time a lawsuit forced it to cease publication in October 1864, the education question had temporarily faded. Reconciliation having failed, Palmer and the conservatives had once again manipulated Protestant fears of Catholic aggression to win re-election in January 1863.

The liberals, who traditionally enjoyed Catholic electoral support, returned to power in 1867 under George Coles. On 3 March 1868 McIntyre formally petitioned the government to subsidize St Dunstan’s College and three convent schools, basing his plea on the simple observation that these schools were doing the public education system’s work for it. (Nearly 500 students were being taught in “his” schools, three-quarters of them at no charge.)

Threatened with the loss of its Protestant supporters, the liberal ministry refused to submit the bishop’s petition to the House of Assembly. The liberals, under Robert Poore Haythorne, were re-elected in July 1870. Impatient with the party’s vaccillation on the education question, a number of Catholic liberals, headed by George William Howlan* and Andrew Archibald Macdonald*, defected to James Colledge Pope*’s conservative party in August, bringing down the new government.

Over the next three years the issue of providing public money for the “Bishop’s schools” was one of the elements, along with debates over confederation and railways, complicating an unstable political situation. During this period McIntyre reached the pinnacle of his political power. Following the death in 1867 of Edward Whelan*, a Catholic liberal stalwart, McIntyre came to dominate the legislature’s Catholic members. In almost dizzying succession he tried to swing their support behind whichever political leader seemed most likely to endorse his educational demands, which now encompassed a complete separate school system funded from the public purse.

A staunch confederate, McIntyre hoped to entrench denominational schools in any agreement with Canada. When financial chaos finally drove Prince Edward Island into serious negotiations with the dominion in 1873, the bishop urged Catholic mhas to support the conservative leader, J. C. Pope, in the April election precipitated by the confederation issue. Again on McIntyre’s advice, the Catholic members helped the victorious Pope form a government, but when the premier neither legislated denominational schools nor made them part of his negotiations with Canada the bishop furiously demanded that the Catholic members vote against confederation. Convinced of its necessity, and finding their political honour at stake, they refused. Apparently out of spite, McIntyre campaigned for the Liberals in the Island’s first federal election, held in September 1873. The Liberals, now adamant advocates of a non-denominational school system, coolly accepted his support without making any concessions whatever. Henceforth, the bishop’s political influence waned.

After another hiatus the education question became the central issue in the provincial election of 1876. A mostly Liberal, “Free School” coalition, ably led by Louis Henry Davies*, advocated a nondenominational public school system. For lack of a better champion, McIntyre endorsed Pope, who promised a sort of “payment for results” scheme that stopped short of accepting the principle of separation. The Liberals won handily, and the Public Schools Act of 1877 enshrined the non-denominational system in law.

McIntyre organized petitions protesting the new education act and personally lobbied the federal government in Ottawa for its disallowance. His efforts unavailing, he reached an accommodation with Premier Davies which continued the diocese’s de facto Catholic school system. With that, McIntyre largely withdrew from politics, devoting his considerable energies to administering the diocese. As denominationalism’s political manifestations subsided, so did open sectarian conflict.

In August 1885 McIntyre celebrated his silver jubilee as bishop in Charlottetown amid much pomp. Shortly afterwards, however, he began to suffer increasingly from heart trouble. By 1889 he had himself picked his successor, Father James Charles MacDonald, rector of St Dunstan’s College. McIntyre pressed MacDonald’s nomination despite opposition among the Maritime bishops, even pursuing it during his last ad limina visit to Rome in 1889. The bishop had his way one last time. On 28 Aug. 1890 MacDonald was consecrated titular bishop of Hirena and coadjutor to the bishop of Charlottetown with right of succession.

A last fling at politicking, on behalf of Howlan, a Conservative, in early 1891, aggravated McIntyre’s heart condition. Still, he could not rest, and death found him in Antigonish, N.S., at the home of Bishop John Cameron* while en route to the Trappist monastery at Tracadie [see Jacques Merle*].

Church historians regard Peter McIntyre as one of his diocese’s greatest bishops, pointing out that in both spiritual and temporal matters it made great strides during his episcopate, so much so that at his death it was only nominally a missionary territory. Although it has to be recognized that this development was linked in part to the Island’s own passage out of the pioneer stage and to the length of McIntyre’s tenure, the bishop’s vigorous leadership was unquestionably an important factor. Secular historians have been less kind to him. Ian Ross Robertson, for example, observes, correctly, that while the bishop “gathered much political power in his hands over the years, he did not learn to use it skilfully.” Yet McIntyre was more than just a heavy-handed prelate who believed that politicians, like priests and parishioners, should do as they were told. He simply was not good at the political game. He was courteous but not suave, dignified but not tactful, clever but not subtle. Conciliation and compromise were not his forte and, when provoked, he lost his temper, his frustration spilling over into bluster, browbeating, and futile recrimination. With McIntyre, given the political and religious climate, negotiation seemed inevitably to become confrontation, and in the political context he never learned to reconcile a Catholic plurality with a militant Protestant majority.

As a Roman Catholic pleading for a special interest group, McIntyre was ultimately a failure. Nevertheless, no other bishop has left so deep an imprint on the diocese of Charlottetown. McIntyre did not preside; he reigned. Generations later, in Island Catholic homes, he would still be known simply as “The Bishop.”

AAQ, 12 A, N: f. 42r; 310 CN, I–II (mfm. at Charlottetown Public Library). Arch. de la Compagnie de Jésus, prov. du Canada français (Saint-Jérôme, Qué.), E. I. Purbeck, corr. avec le supérieur de la Mission canadienne, 1879–89. Arch. de la Propagation de la Foi (Paris), Assoc. de la Propagation de la Foi, Charlottetown, rapport sur des missions (mfm. at NA). Arch. de l’évêché de Bathurst (Bathurst, N.-B.), Group II/2 (Rogers papers) (mfm. at PANB). Arch. of the Diocese of Charlottetown, Pastorals, corr., and other materials relating to the episcopal tenure of Peter McIntyre, esp. in boxes 3/6, 4, 5/3. ASQ, Reg. du grand séminaire, MS 432: 315; Séminaire, 74, 142, 148, 159; Univ., 27, 45, 47, 49, 54, 80–81, 89. Diocese of Charlottetown Chancery Office, Records of St Dunstan’s Univ. (Charlottetown). Private arch., Reginald Porter (Charlottetown), McIntyre memorabilia, including photographs and personal corr.; related materials on Tignish, P.E.I., and its church. Society of Jesus, English Prov., Dept. of Historiography and Arch. (London), AB/5 (Canada), E. I. Purbeck to father provincial, [autumn 1879]. Supreme Court of Prince Edward Island (Charlottetown), Estates Division, liber 12: f.556 (mfm. at PAPEI). Univ. of P.E.I. Arch. (Charlottetown), Materials relating to the history of the Univ. of P.E.I. and its predecessors, esp. St Dunstan’s Univ. P.E.I., House of Assembly, Debates and proc., 1856–77; Journal, 1831, warrant book; 1862, app.A; 1868, app.FF; Legislative Council, Debates and proc., 1855–77. Silver jubilee celebrations of their lordships bishops McIntyre and Rogers, Charlottetown, August 12, 1885 ([Charlottetown, 1885]). Charlottetown Herald, 1864–68; 1870–71; 1881–92, esp. 12 Aug. 1885, 6 May, 10 June 1891. Daily Examiner (Charlottetown), 17, 29 March 1880; 11 Aug. 1885; 26 July, 18 Sept. 1889; 1–2, 4 May 1891. Daily Patriot (Charlottetown), 2 May 1891. Examiner (Charlottetown), 12 Oct. 1857; 1861–69, esp. 15, 28 Aug. 1861; 1 July 1870. Islander, 7 Dec. 1860; 8, 22 Feb., 8, 22 March, 19, 26 July, 2, 9 Aug. 1861; 28 Nov. 1873. Island Guardian, 8 May 1891. Vindicator (Charlottetown), October 1862–October 1864. Georges Arsenault, Religion et les Acadiens à l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard, 1720–1980 (Summerside, Î.-P.-É., 1983). Canada’s smallest prov. (Bolger). F. C. Kelley, The bishop jots it down: an autobiographical strain on memories (3rd ed., New York, 1939). G. E. MacDonald, ‘“And Christ dwelt in the heart of his house’: a history of St. Dunstan’s University, 1855–1955” (phd thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, Ont., 1984). W. P. H. MacIntyre, “The longest reign,” The Catholic Church in Prince Edward Island, 1720–1979, ed. M. F. Hennessey (Charlottetown, 1979), 71–102. J. C. Macmillan, The history of the Catholic Church in Prince Edward Island from 1835 till 1891 (Quebec, 1913). I. R. Robertson, “Religion, politics, and education in P.E.I.” I. L. Rogers, Charlottetown: the life in its buildings (Charlottetown, 1983). Lawrence Landrigan, “Peter MacIntyre, bishop of Charlottetown, P.E.I.,” CCHA Report, 20 (1953): 81–92.

Cite This Article

G. Edward MacDonald, “McINTYRE, PETER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 8, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcintyre_peter_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcintyre_peter_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | G. Edward MacDonald |

| Title of Article: | McINTYRE, PETER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | March 8, 2026 |