Source: Link

BURNS, PATRICK, settler, rancher, businessman, and politician; b. 6 July 1856 near Oshawa, Upper Canada, son of Michael O’Byrne (Byrn, Byrne) and Bridget Gibson; m. 4 Sept. 1901 Eileen Louisa Francis Anna Ellis in London, England, and they had a son; d. 24 Feb. 1937 in Calgary.

Patrick Burns was one of a handful of entrepreneurs who grew rich in the beef industry as it developed roots in western Canada in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1864 he moved with his parents, both Irish Catholic immigrants, and seven siblings from the Oshawa region to a farm near the village of Kirkfield, about 50 miles north. Here he received a rudimentary education at the local school. He does not appear to have enjoyed study and apparently skipped classes a good deal. Partly for this reason there has been a persistent rumor that he was illiterate. This is not correct. A typed letter he wrote to his brother Dominic in 1907 has a coherent postscript paragraph, free of spelling mistakes, in Burns’s hand.

While Burns was living near Kirkfield, he made a friendship and a business decision that were both instrumental to his career as a beef merchant. The friendship was with William Mackenzie*, a young contractor who would one day help Burns in establishing a meat business on a large scale. The business decision was part of his first profitable experience in butchering livestock. In 1877 Patrick and his elder brother John decided to homestead in Manitoba. To raise money Patrick felled trees during the winter of 1877–78. When he went in the spring to collect $100 in back wages, he discovered that his employer was broke. Instead, he had to accept a team of elderly oxen worth about $70. To get as much value as possible out of the animals he slaughtered them and sold their carcasses piece by piece, ultimately bringing in $144.

In the spring of 1878 Patrick and John travelled to Winnipeg by rail, stagecoach, and steamboat. Soon after their arrival they learned that some of the best agricultural land still available was farther west, beyond the reach of existing transportation systems. Lacking the money to purchase horses, they set out on foot to find homesteads. After walking more than 100 miles the brothers filed on separate quarter sections of land at Tanner’s Crossing (Minnedosa). They then went back to Winnipeg to find work so they could accumulate more capital to establish their holdings.

At this time, the route of the Canadian Pacific Railway was being surveyed near Winnipeg, which gave Burns the opportunity he needed. He got a job blasting rock, for which he received $24 a month and his board in a construction camp. After six months he had enough money to buy a team of oxen and some supplies, and returned to his homestead at Tanner’s Crossing. There other settlers joined in a building bee to help him construct his first house – a small log cabin. By using his oxen to drag timber out of the woods for a lumber mill and to plough for neighbours, he was able to acquire a second quarter section. Soon afterwards he got into the freighting business and carried supplies for his neighbours to and from Winnipeg. He also began to deal in cattle, buying from local farmers and selling the animals in the city. In 1886 he tried the experiment of shipping live hogs via the newly completed CPR to eastern markets. Wanting to demonstrate that it was possible to transport livestock over long distances, railway officials were anxious to accommodate him. The company offered him six cars and the promise that if he lost money on the deal, he would receive a rebate for up to the total cost. He later called at the company’s office to announce that the rebate would not be necessary.

Burns stayed at his Manitoba homestead until 1885, when he turned to buying cattle full-time. His business prospered for various reasons. The railway link to the east and the growing number of settlers raised the demand for beef. But his big break came in 1887 when he was engaged by William Mackenzie, Donald Mann, and others to supply meat to their construction camps. His first contract was for the CPR’s “Short Line” across Maine. It was followed by contracts for the Qu’Appelle, Long Lake and Saskatchewan Railroad and Steamboat Company in 1888–89 and later for the lines out of Calgary to Edmonton and Fort Macleod, and finally for the Crowsnest Pass line. According to geographer Simon M. Evans, Burns “learned to establish a mobile slaughtering facility which could move easily as the railhead was extended. He employed a reliable butcher to prepare the meat, and handled the buying and droving himself.” Burns received financial backing from Mackenzie that helped him to buy and sell on a grander scale than would otherwise have been possible. In 1890 he built his first slaughterhouse, on the east side of the Elbow River in Calgary, and began supplying beef to the city and surrounding area. He also developed contacts with merchants in British Columbia to whom he sold both meat and wholesale livestock. He set up his own retail outlets there. To guarantee supply he bought property for a ranch in 1891 some 12 miles southeast of Olds (Alta) with Cornelius J. Duggan and started acquiring cattle both locally and from as far away as Manitoba. The ranch eventually comprised two sections (1,280 acres) of deeded land. By allowing their cattle to graze over countless acres of unclaimed land and employing neighbouring farmers to supply hay and feed in the winter, the partners were able to provide for between 20,000 and 30,000 head of cattle by 1904. In 1898 Burns diversified into mutton and pork; in the next year he purchased the McIntosh Sheep Ranch on Rosebud (Severn) Creek northeast of Calgary.

In the late 1890s during the Yukon gold rush, Burns was one of the first to agree to deliver beef to the miners in Dawson. Two pioneering shipments were made in 1897 and 1898. For the first, the cattle were taken by rail to Vancouver and by ship to Skagway, Alaska, and then were herded over the Chilkoot Pass. The second shipment followed the same route to Alaska but the cattle were driven over the Chilkat Pass and slaughtered at the mouth of the Pelly River. The meat was floated down to Dawson on rafts. Later consignments went by rail as new facilities became available. In the summer of 1902 Burns sent 12 carloads of frozen beef in ice-packed railway cars known as reefers from Calgary to Vancouver. This shipment is reputed to have been the first time any firm west of Toronto and east of Vancouver had shipped carloads of refrigerated meat such a distance. At Vancouver the meat was placed on a cold-storage steamer bound for the Yukon Territory.

Burns’s commercial enterprises continued to grow rapidly despite major obstacles. Twice his Calgary slaughterhouse was destroyed by fire. The original plant burned down in 1892 and was replaced with a property purchased from the Canadian Land and Ranch Company. This facility was opened in 1899 and enlarged in 1906. After its loss in 1913 Burns constructed an expanded, modern plant, which still stands in the Calgary stockyards as part of a performing-arts complex. In 1902 Burns had bought the string of shops and slaughterhouses owned by fellow meat marketer William Charles James Roper Hull* of Calgary. At this stage, as local journalist Leroy Victor Kelly* noted, he became the “acknowledged beef king of the West.” The deal included Hull’s Bow Valley Ranche at Fish Creek south of the city. Using the ranch as support for his meat-packing business, Burns enlarged the property from 4,000 to about 12,500 acres by further land purchases and built a feedlot for 5,000 head of cattle.

In 1905 Burns incorporated his packing and other meat houses under a dominion charter as P. Burns and Company (in 1909 it would become P. Burns and Company Limited). In 1906, following the province’s amendment of the territorial ordinance on brands, he registered his well-known Shamrock brand. Over the next quarter century he established packing plants at Edmonton, Vancouver, Regina, Prince Albert, Sask., Winnipeg, and Seattle. These facilities made the slaughtering process more efficient, and enabled more parts of the animals to be used for such things as household goods and pharmaceuticals. Consolidating his business, Burns bought out or started more than 100 retail meat shops in the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia and set up export agencies in London, Liverpool, and Yokohama, Japan. In 1920 a strike in the Calgary plant demonstrated that, despite the economic downturn following World War I and high cattle losses following a severe winter, Burns was in a strong enough position to refuse the workers’ terms.

Diversifying into foodstuffs other than red meat, Burns bought or established some 65 creameries and cheese factories in places such as Calgary, Moose Jaw, Sask., and Edmonton between 1909 and 1919. In the mid 1920s he founded Palm Dairies Limited as the umbrella company for all his dairy businesses. It was one of the largest distributors of creamery butter in Canada. As well, Burns eventually owned almost 30 wholesale provision and fruit houses. Most of these derived from two big companies, Scott Fruit and National Fruit, which he acquired in 1926 and merged into the Consolidated Fruit Company.

Burns continued to acquire ranching properties, presumably in part because increasing settlement was reducing available public land and farmers resented the “pirate herds” of cattle that were allowed to wander freely by Burns and other ranchers. He came into possession of some smaller holdings as a consequence of their proprietors’ insolvency: several ranchers in southern Alberta turned over their titles because they were unable to repay the credit or loans he had extended to them. Bigger operations were obtained through purchase or lease. He bought the 7,000 deeded acres of the CK Ranch on the north side of the Bow River about eight miles west of Calgary in 1905. Originally owned by Charles Edwin Banks Knight, it became a dairy farm when Burns established a herd of purebred Holstein cattle and marketed their milk and cream in Calgary. He bought the 3,300-acre Ricardo Ranch near the city in 1906. In 1910 he purchased the outfit created by John Quirk near High River and the properties that became known as the Kelly-Palmer Ranch south of the Little Bow River, and took over the lease of the Colonel A. T. Mackie spread of some 150,000 acres on the Milk River. Then he added the Imperial Ranch and the Circle Ranche, both near the Red Deer River, to his holdings. By the beginning of World War I, Burns had more than 400,000 acres under his control, and more than 30,000 head of cattle. In 1917 he leased the 37,500 deeded acres of the famous Walrond Cattle Ranch in the foothills north of Pincher Creek. That same year he sold the Quirk, Kelly-Palmer, Mackie, and Imperial but in 1918 he replaced them with the Rio Alto on the Highwood River and the Lineham on Sheep Creek (Sheep River), close to Calgary. In 1923 he bought the Glengarry (also known as the 44) west of Claresholm.

In 1927 Burns purchased the Bar U and the neighbouring Flying E, respectively on the Little Bow River and Willow Creek. The Bar U, also known as the North-West Cattle Company, was one of the first great ranches in the Canadian prairie west. It had been started by Frederick Smith Stimson* and backed financially by the wealthy Allan family of Montreal. Burns paid over $400,000 for the ranch’s approximately 37,000 deeded acres and the rights to its leased land, $50 per head for its cattle, and $40 per head for its horses with calves and foals thrown in (the total amount paid for livestock was about $300,000). Burns bought both these operations from the estate of the celebrated George Lane*, the American who had become the cattle foreman for the Bar U in the 1880s. Burns knew and admired Lane, who had been one of the most respected members of the western cattle fraternity.

In 1928 Burns sold P. Burns and Company Limited to the Dominion Securities Corporation in Toronto. The deal was widely reported to be worth $15,000,000. In fact, Burns was paid $9,613,837.31 for delivering up all the shares of the company and he then bought back the ranching properties consisting of 300,000 acres of deeded and leased land, and including some 25,000 cattle, for $4,038,837.31. This left Dominion Securities in control of the packing plants and related industries. Burns remained a small shareholder and became chairman of the board of directors. His nephew John Burns, who had formerly been general manager, was made president of the company, while the former vice-president, Blake Wilson, continued in his office. The sale gave Burns the money to purchase the 76 Ranch on the Frenchman River in Saskatchewan, and, in Alberta, the Two Dot near Nanton, where he raised sheep, and the Bradfield operation at Priddis.

Burns’s life was not picture perfect, however. Not all his business interests proved successful. He had made an attempt to compete in the United States creamery market with a plant in Seattle, but decided to close it four years later. Although his investment in Mexican copper mining apparently paid well, he spent tens of thousands of dollars trying to establish a coalmine near Sheep Creek, while mining ventures in Rossland and other British Columbia coal towns appear to have brought less than spectacular rewards. In accumulating stocks in oil companies in Alberta’s Turner valley he seems to have profited only sporadically.

A source of consternation was public suspicion of unfair dealing that dogged Burns during much of his career. This distrust was a consequence of his meteoric rise as a businessman. He got rich trading in cattle and beef and, under frontier conditions, he faced very little competition. His early specialty was purchasing cattle that gave coarser meat and marketing them to railway-construction crews and mining-town labourers. There were many cattle of this type for two reasons. The west’s early herds, principally from the United States, displayed characteristics of the Texas Longhorn, being tall, thin, and unlikely to flesh up well. Secondly, most farmers and ranchers who settled the Canadian west attempted to fatten their stock on grass, a very undependable method. Without short, mild winters, plentiful rains, and lush grass, cattle tended not to fill out. Their meat was often not well marbled, and consequently was stringy and anything but tender. William Mackenzie’s business contacts and financial backing meant that Burns could easily buy poor-quality animals at his own price. This situation naturally caused some cattlemen to believe that he commonly took advantage of them.

What seemed to vindicate their suspicion was the fact that there appeared to be a conspiracy between Burns and the other big middleman on the ranching frontier, the firm of Gordon and Ironside of Winnipeg (Gordon, Ironside, and Fares after 1897). Just before the turn of the century William Henry Fares and George Lane, both later partners of James Thomas Gordon and Robert Ironside*, usually worked with or for Burns in purchasing livestock. Gordon and Ironside generally bought the well-finished cattle that could be marketed in eastern Canada and overseas. Even some of Burns’s close friends considered this splitting of the beef market to be evidence of unfair teamwork. Thus, for instance, in 1900 Alfred Ernest Cross expressed the opinion that “there are practically only two buyers here, and in fact it nearly all comes through one as he sells the exporters to the other after buying all the beef and uses the rough stuff himself, thus leaving the seller more or less at his mercy.” At this stage Cross was prepared to forgive his friend because “he has shown far more mercy than any one could expect.” Three years later, however, he sounded less accepting. “We are trying,” he said, “to get a reasonable price, and not sell our cattle for far less than they are worth as was the case last year. What we want is to establish a fair market without any favors so that we know we can get at any time the right market value for all or any of our beef cattle and not go round with your hat in your hand at the mercy of one or two concerns.”

In 1907 a joint Manitoba–Alberta body, the Beef Commission, was set up to examine the meat trade and allegations of combination among western cattle dealers. Called upon to testify, Burns made it clear that he deeply resented the accusation of price fixing. “Without Pat Burns,” he declared, “the western country would starve in ten days,” and he stated in no uncertain terms his belief that he alone was up to the task of marketing the ranchers’ produce. Unquestionably he played a crucial role in the formation of the beef industry in western Canada. One can understand the ranchers’ fears, however. It is telling, and perhaps somewhat ironic, that as many of the big cattlemen sold out, their operations were bought up by Burns. There can be little doubt that some, perhaps all, of these ranchers gave up because they could not make their operations pay. If they had received a bigger share of the market price, many might have been able to stay in business. It could not have escaped the ranchers’ notice, furthermore, that the two principal firms acting as middlemen generally seemed to garner most of the industry’s profits. The findings of the Beef Commission exonerated both P. Burns and Company and Gordon, Ironside, and Fares of price fixing, but not all of the farmers and ranchers may have been equally convinced.

Burns attained a great deal of public acclaim in the west and across the country during his lifetime. He was awarded the rank of knight commander of the Order of St Gregory the Great by the Vatican in 1914 in recognition of his service to the Roman Catholic Church and the public. He supported the Liberal Party and in 1923 was offered a seat in the Senate, which he refused because of his heavy workload. When the offer was made again in 1931 after the death of Prosper-Edmond Lessard, he was close enough to retirement to accept; he would sit as an independent. The appointment was announced on 4 July during Calgary’s huge celebration of his approaching 75th birthday. Some 750 guests attended a banquet, including “more prominent citizens, nationally known government officials, agriculturalists, heads of industrial enterprises, artists and journalists than ever gathered at a similar event of this kind in the west.” Conservative prime minister Richard Bedford Bennett*, a personal friend despite Burns’s Liberal leanings and his one-time solicitor in Calgary, was unable to attend but he sent a congratulatory message. It was read before the audience along with telegrams from Governor General Lord Bessborough and the Prince of Wales, who had bought the E.P. Ranch next to Burns’s Bar U. A 3,000-pound birthday cake was distributed to some 15,000 people.

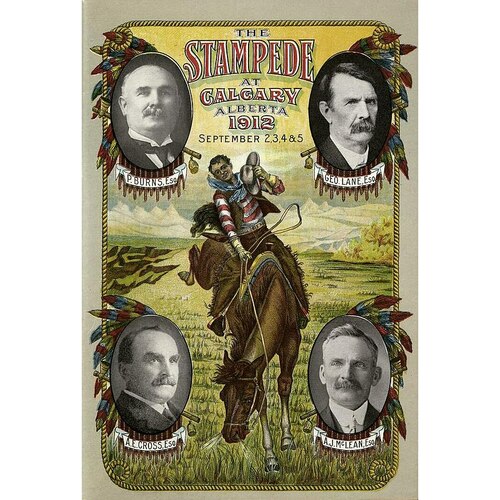

These tributes were offered in recognition of Burns’s business acumen but they were also acknowledgements of his work for public and charitable causes. The community-spirited action for which he is probably best known is the organizational and financial backing he provided together with Archibald James McLean, A. E. Cross, and George Lane – the “big four” cattlemen – for the first Calgary Stampede held from 2 to 5 Sept. 1912. His support of this inaugural event, a rodeo and frontier-days presentation, was just one of Burns’s numerous public-spirited deeds. When a rockslide devastated the mining community of Frank (Alta) on 29 April 1903, he offered aid before anyone else. After the town of Fernie, B.C., was wiped out by fire some five years later, he sent its citizens a freight car of food. During World War I he and his company contributed $50,000 to equip the Legion of Frontiersmen. After the war he was made an honorary member of the Calgary Aero Club (now the Calgary Flying Club) “in token of … [his] interest in aviation and his gift of two airplanes” to support the war effort. He made a substantial donation to the construction of the Canadian Memorial Church, built by the Reverend George Oliver Fallis* to honour those who had served in the war. He contributed to Holy Cross Hospital in Calgary and gave 200 acres of land and a regular supply of meat to the Lacombe Home, founded by Father Albert Lacombe* in Midnapore, Alta. It is said that while the Catholic church near the Lacombe Home was being painted at his expense, he noticed the shabby condition of the nearby Anglican church and told his workers to paint it too. Besides providing free office space in one of his Calgary buildings to the Western Stock Growers’ Association, Burns helped to improve western dairy herds by arranging to sell good Jersey and Holstein breeding stock to farmers on long-term payment schedules. He gave financial aid to two sisters struggling to establish the Braemar Lodge, which became an important Calgary hotel. He supported talented artists by, for example, sponsoring the operatic career of Isabelle Burnada and the musical training of Odette de Foras. When Calgary celebrated his birthday in 1931, he announced that “for each single unemployed man or woman in the city a ticket good for 50 cents, would be issued at his expense for the purchase of food and that to each married unemployed man he would give a five pound roast of beef. ‘I feel,’ he said, ‘that during the Stampede celebration and on the occasion of my 75th birthday, I would like to do something for the citizens who during these difficult times [the Great Depression] are unable to obtain employment.’”

Burns had his own problems in the 1930s. Most immediate were the financial difficulties of P. Burns and Company Limited. In 1931 he was obliged to invest $200,000 so that it could pay the interest on its bonds. Even then the business continued to flounder: in 1934 it was announced that the company had not paid dividends on its preferred shares since 17 Oct. 1930, or any interest on its bonds since 1 June 1932. A restructuring agreement enforced by the appellate division of the Supreme Court of Alberta on 25 April 1934 basically allotted all the company’s preferred shares to the bondholders. P. Burns and Company Limited would soldier on and eventually expand and prosper, although Burns did not live to see this development.

His other major financial headache in later years was the fall in his personal net worth. This decline resulted not just from the problems of the company. At the end of 1928, after the sale to Dominion Securities, Burns valued his holdings in stocks and property at $9,211,222.41. Over the course of the depression he stubbornly continued to declare his assets at close to this sum despite warnings from his accountants that “attention should be given to the setting up of reserves to provide for probable losses on Accounts Receivable, particularly those included in the Cash Advances, many of which appear to us to be very doubtful as to recovery.” The accountants pointed out as well that “probable shrinkage in the value of investments has not been dealt with.” After his death his estate was assessed at $3,833,413.34 – a vast sum for the times, but well short of his calculations. The decreasing value of his life’s work must have haunted the senator during his declining years.

Beyond business concerns, there was another aspect of Burns’s life that was not ideal. His family situation was difficult at best. He and his wife, the daughter of a rancher from Penticton, B.C., clearly had their problems. Some evidence suggests that Burns made a genuine attempt to make his wife happy. Between 1900 (a year before his marriage) and 1903 he spent approximately $40,000 to build a family mansion on 13th Avenue West in Calgary. Neo-Gothic in design, with steeply pitched gables, ornate sandstone carvings, and a three-storey tower, Burns Manor had 18 rooms, including 10 bedrooms, 4 bathrooms, and a conservatory. Oak from eastern Canada was used extensively for the interior, while furniture imported from England and a landscaped garden helped to sustain an Old-World air. In its time Burns Manor, which had been commissioned from the prominent architect Francis Mawson Rattenbury, was probably the most luxurious dwelling in Calgary. However, it was not enough to give the Burnses a strong domestic bond. They were separated by both age and religion. When they married in 1901, Burns was 45 years old and Eileen only 27; throughout his life he strongly adhered to the Catholic faith, while she was a Protestant. Their major problem, however, seems to have been that he was addicted to work: even their wedding, at a registry office in London, was arranged to coincide with a business trip. Largely because business occupied so much of Burns’s time, Eileen found her life in Calgary both lonely and unfulfilled. Unable to adjust, she went to live in California and then Vancouver. In the early 1920s she was diagnosed with cancer, and died on 7 Sept. 1923, shortly before her 50th birthday. It seems that Burns’s relationship with his one child was not close. Patrick Thomas Michael did not enjoy his father’s robust health, and he does not appear to have shown any sustained interest in the commercial undertakings so important to Burns. On 18 Sept. 1936 Patrick was found dead in his bed at his father’s home, presumably because of a heart attack. He was 30 years old. Burns himself had suffered a stroke in 1935 (as a consequence of which his Senate seat had been declared vacant in June 1936 because of nonattendance), and died less than six months after his son. He was buried in St Mary’s Cemetery in Calgary.

Burns was as generous at his death as he had been in his life. Among the beneficiaries named in his will were the Lacombe Home, the Salvation Army, the Children’s Shelter of Calgary, the widows and orphans of men in the city’s police force and fire department, the Roman Catholic bishop of Calgary, the Collège Saint-François-Xavier in Edmonton, the Navy League of Canada, the Canadian Red Cross Society, the Junior Red Cross, the British Empire Service League, the Canadian Legion’s tuberculosis section, the 103rd Regiment (Calgary Highlanders), the Boy Scouts Association in Alberta, and the Southern Alberta Pioneers’ and Old Timers’ Association.

GA, M 160, M 7771, M 8688, M 8780. Calgary Albertan, 6 July 1931. Calgary Herald, 25 June 1907; 3 July 1919; 16, 20 May, 11 Oct. 1927; 10 May 1928; 4 July 1931; 3 Sept. 1955; 29 Sept. 1960; 1 Feb. 1998; 26 Sept. 1999. Calgary News Telegram, 19 March 1912. High River Times (High River, Alta), 4 Dec. 1930. Times (High River), 13 Nov. 1985. Western Farmer (Calgary), 10 July 1931. David Bright, “Meatpackers’ strike at Calgary, 1920,” Alberta Hist. (Calgary), 44 (1996), no.2: 2-10. W. M. Elofson, Frontier cattle ranching in the land and times of Charlie Russell (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2004). Encyclopedia Canadiana, ed. K. H. Pearson et al. ([rev. ed.], 10v., Toronto, 1975). Encyclopedia of music in Canada (Kallmann et al.), 178. S. M. Evans, The Bar U & Canadian ranching history (Calgary, 2004). J. H. Gray, A brand of its own: the 100 year history of the Calgary Exhibition and Stampede (Saskatoon, 1985). L. V. Kelly, The range men (75th anniversary ed., High River, 1988). H. C. Klassen, A business history of Alberta (Calgary, 1999); Eye on the future: business people in Calgary and the Bow valley, 1870-1900 (Calgary, 2002). [J. W.] G. MacEwan, Pat Burns, cattle king (Saskatoon, 1979). Peter McKenzie-Brown and Stacey Phillips, In balance: an account of Alberta’s CA profession, 1910-2000 ([Edmonton], 2000). B. P. Melnyk, Calgary builds: the emergence of an urban landscape, 1905-1914 (n.p., 1985). A. F. Sproule, “The role of Patrick Burns in the development of western Canada” (ma thesis, Univ. of Alta, Edmonton, 1962). Who’s who in Canada, 1932/33.

Cite This Article

Warren Elofson, “BURNS, PATRICK,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 11, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/burns_patrick_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/burns_patrick_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Warren Elofson |

| Title of Article: | BURNS, PATRICK |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2011 |

| Year of revision: | 2011 |

| Access Date: | March 11, 2026 |