Source: Link

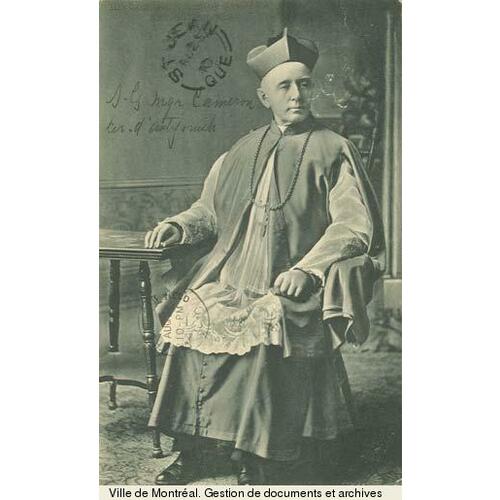

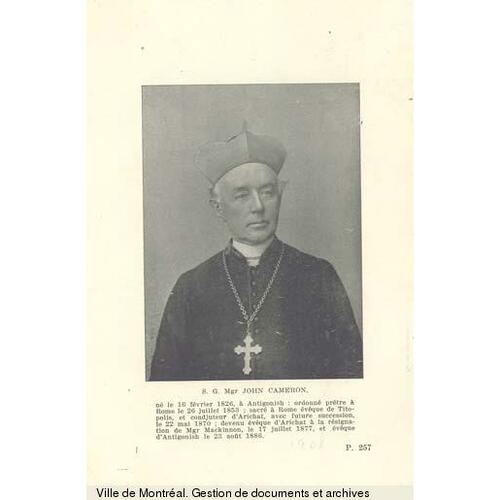

CAMERON, JOHN, Roman Catholic priest and bishop; b. 16 Feb. 1827 in St Andrews, N.S., son of Red John Cameron (Iain Ruaidh) and Christena (Christina) MacDonald; d. 6 April 1910 in Antigonish, N.S.

John Cameron’s father left Scotland with three brothers early in the 19th century and went to Southside Antigonish Harbour, N.S., where they were befriended by Lauchlin MacDonald, an earlier immigrant. Although Clan Cameron had been Presbyterian since the Reformation, Red John converted to Catholicism upon his marriage to one of MacDonald’s daughters.

The youngest of eight children, John shared the chores of the family farm and early absorbed the sense of duty that would characterize his religious career. He attended the village school until he was 11 and then enrolled in the first class of St Andrew’s Grammar School, which had been established by the parish priest, the Reverend Colin Francis MacKinnon*. From the beginning he showed an aptitude for academic work, and his teachers gave him every encouragement. On MacKinnon’s advice, at the age of 17 he left Nova Scotia to begin theological studies at the Urban College in Rome.

Adjusting easily to seminary life, Cameron showed in his letters home a maturity hardly to be expected in a youth from rural Nova Scotia. The didactic tone of his correspondence suggests that he already felt a responsibility to teach and explain. After eight months he told his father that he had a “fair knowledge of the Italian, can read, write, speak and understand it.” The violence the young seminarian witnessed when Rome was racked by revolution and war in 1848 and 1849 made him a lifelong enemy to the foes of established authority. He would constantly defend the supremacy of the pope and later sympathize with the views of the ultramontanes.

Cameron was ordained to the priesthood on 26 July 1853, and he remained in Rome for a further ten months in order to receive his doctorates in theology and philosophy. During this time he was secretary to Alessandro Cardinal Barnabo, secretary to the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda, an appointment which suggests that he was held in high regard. In this position he made many acquaintances within the hierarchy of the church and familiarized himself with its bureaucracy. In 1853 he assisted the vice-rector of the Urban College. After leaving Rome in May 1854, Cameron spent three more months in Europe at the request of MacKinnon, now bishop of Arichat, in order to recruit priests and nuns for the diocese. He arrived home on 10 September. To the sobriety and prudence characteristic of his Presbyterian ancestors had been joined an obedience to the dictates of Rome and an unbending rigidity in matters of Roman Catholic doctrine.

The month he returned Cameron was appointed rector and professor at the academy in Arichat, established in 1853 by MacKinnon in order to educate young men for the priesthood and give Scottish Catholics an opportunity for professional careers. MacKinnon had, however, always intended to start a college in Antigonish, the centre for a large congregation of Scottish Catholics, and most of the faculty and staff of the academy moved there when a building was made available in 1855. Cameron served as rector of the new college, which was named St Francis Xavier, until 1858; he also taught theology and was pastor of the sprawling parish of St Ninian’s. Having mastered several languages and gained doctorates he was considered scholarly; because he followed a temperate life-style he won respect for his diligence and dedication.

Although Antigonish was MacKinnon’s residence from 1858, the seat of the diocese remained in Arichat. Cameron was transferred to Arichat in July 1863 because of a dispute there involving the resident pastor and some parishioners and probably because of a disagreement over politics with MacKinnon. He was appointed rector of Notre-Dame de l’Assomption Cathedral and also became vicar general of the diocese, a position he would hold for seven years. His reputation as a religious administrator soon became firmly established. Later in the decade, when MacKinnon’s failing health made him less capable of dealing with the business of the diocese, some priests sought Cameron’s advice on administrative affairs. Cameron was much concerned during the 1870s about the slow growth of St Francis Xavier but could do little to effect change from Arichat. His administrative abilities had, however, been recognized in March 1870, when thanks to MacKinnon’s recommendation he was appointed coadjutor with the right of succession. In addition, he served again as vicar general between 1873 and 1877. Rome too had a regard for Cameron’s competence: in 1871 he was asked to settle a jurisdictional dispute at Harbour Grace, Nfld. During the 1880s he would be used as an apostolic delegate by the papal authorities during a nasty imbroglio involving the archbishop of Halifax and the Sisters of Charity [see Mary Ann Maguire, named Sister Mary Francis], and in a diocesan dispute at Trois-Rivières, Que. [see Louis-François Laflèche*].

Cameron reached the major milestone in his career on 17 July 1877, when he succeeded MacKinnon as bishop of Arichat. Both had long intended to make Antigonish the seat of the diocese, and Cameron moved there in 1880. On 23 Aug. 1886 the name of the diocese was changed from Arichat to Antigonish; the large stone church in Antigonish, completed in 1874, became its cathedral. The 1880s was a decade of major accomplishments, notably in administration. The debt incurred in the building of the cathedral was paid and a new wing was added to the college; in addition, an episcopal residence was constructed and the Congregation of Notre-Dame was brought to Antigonish.

At the same time Cameron gave new vigour to St Francis Xavier, which had become a university in 1866. He imposed levies on each parish in support of the college after its government grant was withdrawn in 1881, and for the remainder of his life he strove constantly to improve the institution by constructing buildings, strengthening the faculty, promoting new programs in the humanities, commerce, and science, and introducing the ma and b.litt. degrees. Much of his attention was directed to it, and he has rightly been called the college’s “second founder.” Cameron’s educational philosophy may be summarized by the phrase “educating the whole man,” a popular slogan among Catholic educators of his day. As part of this approach, he sent bright theology students to seminaries in Rome, Quebec, or Montreal for advanced training in theology and other disciplines; those chosen returned home fluent in two or more languages.

Cameron was a firm believer in the importance of a better general education for women. Writing in 1895 to Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks*], he stated that “those who limit women’s mission and sphere of action to the nursery misinterpret the word of God.” In 1883 he had had the Congregation of Notre-Dame establish a convent school for girls in Antigonish. The school, renamed Mount St Bernard, later became a women’s college, and it was affiliated with St Francis Xavier in 1894. In 1897 four of its students were awarded bas by St Francis Xavier, the first Catholic university in North America to offer to women courses which led to a degree.

The bishop was also more progressive than the majority of his Maritime colleagues in providing French-speaking priests for the Acadians of his diocese. Moreover, he sought to assist ethnic groups to preserve their languages and cultures by prescribing catechisms in French and Micmac and by helping to compile a catechism in Gaelic. In this endeavour he was probably the most active Catholic prelate in 19th-century Nova Scotia.

On matters which affected the faith and morals of his people, Cameron was inflexible. Periodically he directed his attention to the cause of temperance, issuing pastoral letters and urging his priests to speak out against the abuse of alcoholic beverages. The increasing popularity in the 1890s of round dances distressed the bishop because he disapproved of “the improper intimacies between young people” which resulted. Like many Christian clerics of his day, Cameron believed that people had constantly to guard against committing sins of the flesh. In seeking to warn his flock of the dangers of sexual intimacy outside marriage he issued pastoral letters which left little room for misinterpretation. The bishop also insisted on the observance of church regulations for ritual, rubrics, and dogma, and the diocese was constantly made aware of edicts from Rome which affected the laws of the church.

Although Cameron gave the appearance of ruling a theocratic kingdom, he did not normally abuse his episcopal power. He did, however, overstep himself in his involvement in politics. His first venture was in 1877, when John Sparrow David Thompson*, a Halifax lawyer and a convert to Catholicism, was suggested as a possible Conservative candidate for a provincial by-election in Antigonish County. The bishop had at one time supported the Liberals, but he believed that well-educated Catholics should take a greater role in public life, and Thompson had impressed him. He let it be known that he favoured Thompson, who won handily.

The result did not leave Cameron unscathed: he was attacked by Liberal politicians and newspapers for interfering in the political process. The criticism was repeated when he supported Thompson in provincial and federal elections up to 1891, several of which Thompson would not have won without his help. Although it was not thought unusual at the time for churchmen to be involved in politics, Cameron made himself more vulnerable to criticism than other Maritime prelates because of the direct and authoritarian manner in which he aired his views. Moreover, in backing Thompson he became involved in the grubby side of elections and enmeshed in a web of patronage.

The attacks on Cameron’s interference in politics were harshest during the federal election campaign of 1896, when the Manitoba school question was a major topic of debate [see Thomas Greenway]. Cameron was the only Maritime bishop to advocate strongly and publicly the restoration of Catholic rights in Manitoba. Arguing that the school question was a religious matter, he ordered that a pastoral letter be read in all parishes just prior to the election. In it he stated that Catholics had to support their coreligionists in Manitoba and vote for the remedial legislation of the Conservatives. A majority of Catholics in the riding of Antigonish did not agree and helped elect a Liberal. The feeling against the letter in Heatherton, ten miles east of Antigonish, was so strong that when it was being read at least 40 parishioners walked out of the church. Incensed, the bishop accused the protesters of having insulted the priest by leaving; they countered that they were being coerced into voting for the Conservatives. Cameron denied the protesters the right to the sacraments until they apologized for causing scandal, and it was not until 1900, after the intervention of the apostolic delegate, that the dispute was resolved. The election also tarnished Cameron’s image in Rome. Until then he had been held in great respect by the church authorities, but his involvement in the campaign led them to reprimand him.

The bishop’s administrative skills were sorely tested after 1900, when new parishes had to be created almost overnight because of rapid industrialization in Cape Breton. Although he succeeded in meeting the challenge, he did not fully understand the changing social conditions wrought by the sudden influx of different racial and ethnic groups into his diocese. Nor did he completely comprehend the problems caused by industrialization and urbanization, having no experience of either development. Little is known about Cameron’s views of the labour movement and trade unions, but the church as a whole reacted in a conservative manner to the rise of trade unionism in Cape Breton.

By the year of his death Cameron had achieved great successes. He had paid off a large diocesan debt incurred over the years and had had religious orders establish convents, hospitals, schools, and a home for the aged. He had also been mainly responsible for the creation of the Sisters of St Martha of Antigonish, founded in 1894 to perform domestic duties at St Francis Xavier (the order later moved into educational, hospital, and social work). Twenty-six new parishes had been formed, half in industrial Cape Breton. There were 93 priests, more than half of whom had been ordained by Cameron, and ten monks in a Trappist monastery at Tracadie. Moreover, the great majority of the priests had studied at St Francis Xavier, which had become the leading Catholic university in the Maritimes. By 1910 its staff consisted of nine priests and thirteen laymen, who offered a solid education as a basis for professional studies.

John Cameron’s long-lasting influence with Thompson and other politicians such as Sir Charles Tupper* and the respect in which he was held by his ecclesiastical peers give him a claim to a position of national importance. But although he was an outstanding churchman and achieved much as an administrator and educator, his political partisanship diminished his lustre.

A full-length portrait of Cameron hangs in the Special Coll. Sect. of the Angus L. Macdonald Library at St Francis Xavier Univ., Antigonish, N.S. It is reproduced in black and white in Waite, Man from Halifax. There is also a marble statue on the grounds of St Francis Xavier.

Arch. of the Diocese of Antigonish, A. A. Johnston files, ms sketches, no.164. Archivio della Propaganda Fide (Rome), Scritture riferite nei Congressi, America settentrionale, 6 (1849–57): ff.539–40v; 664–65v (copies in St Francis Xavier Univ. Arch., Cameron papers). NA, MG 26, A, 273, Thompson to Macdonald, 8 Dec. 1888. St Francis Xavier Univ. Arch., Cameron family coll.; Cameron papers; Sister John Baptist [Cameron], “A brief sketch of the Most Reverend John Cameron” (1950); Sister M[ary] Ignatius, “The Most Reverend John Cameron, D.D.” (1951). Morning Chronicle (Halifax), 11 Dec. 1877. D. [F.] Campbell and R. A. MacLean, Beyond the Atlantic roar: a study of the Nova Scotia Scots (Toronto, 1974), 130. A. A. Johnston, A history of the Catholic Church in eastern Nova Scotia (2v., Antigonish, 1960–71). St Francis Xavier Univ., Academic calendar (Antigonish), 1990–91.

Cite This Article

R. A. MacLean, “CAMERON, JOHN (1827-1910),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cameron_john_1827_1910_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cameron_john_1827_1910_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | R. A. MacLean |

| Title of Article: | CAMERON, JOHN (1827-1910) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |