Source: Link

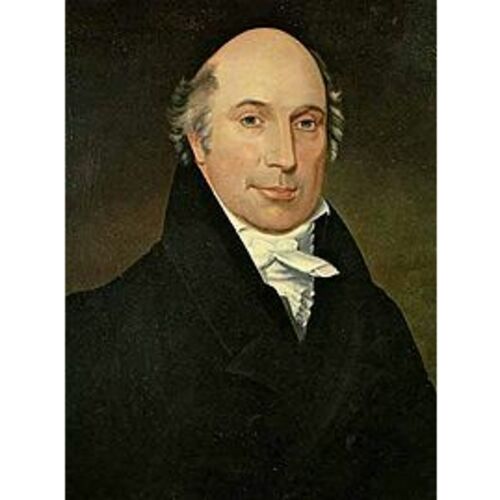

CARSON, WILLIAM, physician, author, farmer, political agitator, newspaperman, politician, and office holder; baptized 4 June 1770 in the parish of Kelton, Scotland, son of Samuel Carson and Margaret Clachertie; m. Esther (Giles?) (d. 1827), and they had five daughters and three sons; d. 26 Feb. 1843 in St John’s.

William Carson attended the University of Edinburgh’s Faculty of Medicine from 1787 to 1790 but, despite his later claims, it appears that he did not graduate. According to his own accounts, he practised medicine in Birmingham, England, for 13 or 14 years prior to 1808, and he is listed as a surgeon in that city’s directories for the period 1800–3. While in England, Carson was not politically active; he was, however, a student of politics, choosing as his mentors Charles James Fox and Charles Grey (later Earl Grey). It was presumably from these two men that he imbibed the Whig zeal for reform and constitutional rights that he brought to bear upon the fledgling institutions of Newfoundland. Carson married while in Birmingham, and he later stated that “domestic circumstances” connected with his wife’s family induced him to leave the city. After receiving the advice of “a number of influential Merchants” trading in Newfoundland, he decided to emigrate, arriving in St John’s on 23 April 1808.

Carson’s first appearance in public records relating to Newfoundland occurred in 1810, when he applied for letters patent entitling him to “the exclusive privilege of taking whales” in the island’s coastal waters, by an elaborate, if somewhat fanciful, new method of whaling. The request, which was denied, provides an early illustration of Carson’s impractical but earnest application of mind to the development of the island’s resources. It was in collaboration with the merchants of St John’s, who dominated the loosely regulated and mildly governed community, that Carson began his long career of agitation. In 1811 the British parliament passed an act which in effect took away the public’s right to use certain ancient fishing rooms in the harbour. With the decline of the English migratory fishery, they had become commons, and local merchants and fishermen used them without fee for such purposes as building boats and storing lumber. In November 1811 a meeting of St John’s merchants and other “principal inhabitants” discussed the act, and an address was sent to the Prince Regent requesting that income derived from renting the rooms be used to improve the town and that new legislation be introduced to create a “Board of Police” with the power to receive the rent and spend it for that purpose. The minutes show that those attending understood their actions did not imply “censure upon the Government” though members of the board of police were chosen by ballot. Carson was prominent in these mild transactions, which provoked a controversy in the Royal Gazette and Newfoundland Advertiser – the first sign of something resembling open partisan conflict in Newfoundland – but brought about no change in government policy. In 1812, before an official response to the address was received, Carson published a tract asserting that the act of 1811 had “surprised and alarmed” the inhabitants not only of St John’s, but of the whole island, who held the lack of a legislature among the “misfortunes they felt severely.” Drawing upon John Reeves*’s 1793 work, he described the history of the colony as one of misrepresentation and oppression of the residents by West Country merchants, charged the governors with “ignorance” and illegal, arbitrary behaviour, denounced the naval surrogates (who presided over surrogate courts around the island) as ignorant “of the most common principles of law and justice,” and declaimed against the apparent policy of discouraging agriculture. In a second pamphlet (1813) he declared himself convinced of “the capability of Newfoundland to become a pastoral and agricultural country,” and called for “a civil resident Governor, and a Legislative Assembly.”

The pamphlets were the first literature of political protest in Newfoundland. However much they (no doubt unwittingly) distorted the colony’s history and geography, they showed Carson’s literary skill, his courage, and his complete possession of high-minded Whig rhetoric. It is probable, nevertheless, that Carson mistook the merchants’ desire for increased influence in St John’s to be evidence of a more general desire for change. The tracts infuriated local authorities, and a recommendation was made to Governor John Thomas Duckworth* that libel proceedings be initiated. This recommendation was rejected by the Colonial Office. However, Carson was immediately removed by Duckworth from his only official position, surgeon to the Loyal Volunteers of St John’s. Despite angry protests to both Duckworth and the colonial secretary in London, he was not reinstated. Somewhat inexplicably, Carson always deeply resented the displeasure his behaviour inevitably provoked with a succession of governors, who identified him, not without reason, as the “root and origin” of their difficulties in regulating the colony’s affairs.

Carson’s activities during his early years in Newfoundland were by no means confined to politics. His medical practice in St John’s was successful, and in 1810 he suggested the building of a public hospital, becoming, soon after its completion in 1814, the principal medical attendant. He was actively accumulating land for farming. In June 1812 he requested subscriptions for 20 lectures on scientific subjects, to be given the following winter. Carson’s literary interests manifested themselves in a plan, outlined in 1815, to write a book on the resources and people of Newfoundland, a project he abandoned when he was denied access to government records. Court records show that he was an active litigant and an occasional advocate in popular causes. In 1814, for example, he successfully represented one John Ryan, who was charged with libelling Chief Justice Thomas Tremlett*. Journalism was yet another avocation. On the establishment of the Newfoundland Mercantile Journal in 1815, he contributed a series of articles under the signature Man, in one of which he stated that half of the Bible was “hurtful and useless.” This view triggered a controversy culminating in a sensational libel case in 1817, with Carson as plaintiff. He lost the case, possibly because a servant testified she had heard him “ridicule the Holy Scriptures” and “deny the Divinity of our Saviour” (credible testimony since Carson, though of a Presbyterian family, admitted later to Socinian views). Carson also sounded “peals of constitutional thunder” in the Newfoundland Sentinel, and General Commercial Register, founded in 1818, the earliest reform journal in the colony.

The collapse of Newfoundland’s economy after the Napoleonic Wars touched off debate on its future prospects and created an atmosphere in which the reform movement could grow. By 1815 it was apparent to Governor Sir Richard Goodwin Keats* that the influence of “a Party which affects a popular character” was on the increase in a “too easily agitated” St John’s. Carson’s solution to the growing economic difficulties was simple: an extension of the British constitution to the island and the creation of colonial equivalents to king, lords, and commons. With “a resident government and legislature,” he wrote in 1817, Newfoundland could look forward to “prosperous and happy times.” Exactly how a “Newfoundland Parliament” could “influence the price of fish in a foreign market” was not apparent to one sceptical observer, but by 1817 even the merchants of St John’s were convinced that fundamental changes in the system of government were needed. The British government’s response was to make mild concessions. In 1817 the colony was granted a year-round governor, an improvement for which Carson immediately took credit. In a letter to Colonial Secretary Lord Bathurst, furiously assaulting Governor Francis Pickmore* and giving a catalogue of grievances, he indicated more demands would follow. Yet until 1820 he could find no outrageous abuse with which to attract public attention to the need for reform.

The surrogate courts were an early and favourite object of attack by Carson, for reasons which are by no means obvious. On the whole these courts dispensed justice in a lenient and efficient fashion, calling a jury when the offender demanded one in cases involving amounts greater than 40 shillings. In July 1820, however, two Conception Bay fishermen, Philip Butler and James Lundrigan*, were called before surrogates David Buchan and the Reverend John Leigh*, charged with contempt of court, found guilty, and whipped. In St John’s, Carson and Patrick Morris, an Irish merchant drawn into political agitation for the first time, turned the event into a public sensation. An action in the Supreme Court acquitted the surrogates but the judge, Francis Forbes, rebuked Buchan and Leigh for inflicting the “harsh” punishment. At a public meeting on 14 November where Morris and Carson were prominent, it was resolved to take constitutional means “to have the law repealed” which sanctioned “such arbitrary proceedings.” A petition to the king followed, calling for reform of the system of justice and linking the Butler–Lundrigan case with other grievances, including the need for a “superintending legislature.” Bathurst rejected outright the idea of a legislature, but indicated that Britain had “under consideration” altering the laws pertaining to Newfoundland.

The cause of reform now gained momentum in a city where increasing poverty seemed to underline the need for change. Some “local authority” should be granted, Governor Sir Charles Hamilton conceded, which would “answer every good purpose of a legislature, without its evils.” Throughout 1823 and 1824 Carson chaired a committee of residents pressing for changes in the new Newfoundland bill to come before parliament. When news of its contents reached St John’s, the reformers learned they would have to be content with municipal institutions. Although it was not what Carson had hoped for, he accepted the idea of a corporation for the city, probably anticipating that this change would lead to the larger reform. In June 1824 new laws replaced the surrogate system by circuit courts, enlarged the Supreme Court, made provision for municipal government in the colony, and gave the governor the statutory right to dispose of unoccupied lands. The reformers had had a demonstrable influence in shaping this new constitution.

In January 1825 Carson announced he was withdrawing from politics, giving as reasons “increasing years,” professional duties, and domestic responsibilities. It appears that family illness may have been a factor in his decision. In 1826, however, he was back in the political arena, this time in the bitter dispute over the form of municipal government for St John’s. Carson and Morris now wished to amend the clauses in the 1824 act which authorized an appointed corporation, urging that it be replaced by an elected town council. They also urged that taxes be imposed on the rental value of property, the act having granted the corporation the right to levy “Rates and Assessments” on inhabitants and householders. This proposal angered landlords, and after a turbulent public meeting in May a petition was sent to Governor Thomas John Cochrane* by merchants, opposing incorporation. The dispute appears to have polarized opinion in the city as no other issue had done, and it is possible to see in it intimations of the cleavage between popular and mercantile interests that characterized politics in the colony after 1833. Cochrane reported that people would prefer to have regulations imposed on them by his government rather than see that “either party triumphed over the other.” In effect, the corporation was scrapped. The failure to agree on some kind of municipal authority had an unexpected effect in the Colonial Office, where James Stephen used it to illustrate the need for a legislative council, with some elected members. Clearly it was but a matter of time before a legislature would be granted.

In November 1827 Carson was appointed district surgeon by his friend Chief Justice Richard Alexander Tucker*, administrator in Cochrane’s absence. Out of a “desire to keep the Doctor quiet,” Cochrane on his return confirmed the appointment, which brought an annual salary of £200. The duties consisted of providing medical attention to the poor. Far from keeping Carson quiet, his office seems to have given him more time for politics. In 1828 he was again in the forefront of agitation for representative institutions. Public sentiment in favour of a legislature was rapidly gaining ground in 1830 and 1831, and as it grew so did Carson’s reputation as an avuncular patriot. Once again, worsening economic conditions accented the need for change. In March 1832 news reached St John’s that representative government had been granted. Carson at once offered himself as a candidate in the district of St John’s.

As the election of 1832 approached, the united front the colony had presented to Britain in petitioning for a legislature gave way to the sectarian rivalry which was to dominate politics for the next 50 years. In St John’s the Catholic bishop, Michael Anthony Fleming, endorsed three candidates, including John Kent*, an Irish merchant whose flamboyant electioneering among the Catholics quickly drew him into controversy, and Carson, who had been carefully cultivating Irish support since 1817. As if the endorsement of Fleming were not enough to turn Protestants against him, Carson in August and September made two public attacks upon the Anglican archdeacon, Edward Wix*, who had found heretical notions in a pamphlet by Carson on cholera. Carson replied in the Public Ledger that Wix was “a scourge more terrible than the Cholera itself.” Thus fears of Catholic hegemony in St John’s were stirred by Carson as well as Kent, and whether for this reason or because, as he later maintained in a formal protest to the house, he had been unfairly outmanœuvred at the polls, Carson was defeated in November. He responded in typical fashion. “Submission,” he later wrote, “never gained a point in politics.” In January 1833 the prospectus for a new weekly newspaper, the Newfoundland Patriot, was published. According to Robert John Parsons*, sole owner of the Patriot by 1840, Carson edited the paper from its inception in July 1833 until December. As late as 1835 he was still contributing occasional editorials.

The numbers of the Patriot issued under Carson’s editorship do not survive, but from the responses of other journals and official reaction, it appears the promise made in the prospectus, that the paper would uphold “liberal and constitutional principles” in opposition to the “constituted authorities” in the colony, was fulfilled. Carson’s aggressiveness succeeded in further antagonizing Cochrane and also Henry David Winton* of the Public Ledger; it even angered John Shea, the normally sedate editor of the Newfoundlander, who was advised to “think more of John Kent and Newfoundland, and less of Daniel O’Connell and the Emerald Isle.” The remark reveals Carson’s slight interest in Ireland, now attracting great attention among local Catholics. Nevertheless, it was to the Irish that he had to turn once again for support in a St John’s by-election in December 1833. An even more bitter contest than that of 1832 ensued, with Fleming throwing his support to Carson and effectively forcing his opponent to withdraw. In a savage editorial Winton wrote that Carson’s election had been brought about by the Catholic clergy’s “domination” over their mentally enslaved parishioners. Hereafter, Carson would be an object of persistent attack in the Public Ledger and in another new paper, the Times and General Commercial Gazette, edited by John Williams McCoubrey*. His career as an mha thus began inauspiciously amid much sectarian feeling.

When the house reopened in January 1834, Carson aligned himself with a minority group of “popular” members and allowed himself to be nominated for speaker, in opposition to Thomas Bennett*. Even before the vote, Carson, addressing the clerk, indicated that three members were ineligible to sit, and ought not to take part in the choice of speaker. The vote proceeded, Bennett was elected, and Carson and his friends organized a petition calling for the dissolution of the house and a new election. This first action showed well his future predilections as a legislator. Carson was a parliamentary purist, a determined defender of the rights and privileges of the house against real or imagined incursions of the Council, the governor, the Colonial Office, and private individuals. Although he was concerned with such matters as education, roads, and municipal reform, these did not engage him as much as constitutional nicety, and it is not surprising, for example, to find him in February 1834 plunging the house into a prolonged debate on the eligibility of a bankrupt to hold a seat, at a time when the colony itself was bankrupt and was forced to appeal to the British government to make up a deficiency of £4,000.

It was also clear that there was not a little hypocrisy in his argument that a government contractor such as Patrick Kough* could not sit in the house, when he himself was still district surgeon. However, Cochrane, smarting from several cuts by Carson, dismissed him from his surgeon’s position in March 1834, under the pretext that the imperial treasury was no longer supplying the necessary grant. Carson then informed the governor that supplies had been voted by the house to keep the office filled, on the understanding that he should continue in it. On 9 May the house passed two resolutions of censure on Carson, in effect accusing him of lying. These proceedings evidently caused Carson considerable anguish. The loss of the office may have been a severe economic blow, since, according to Cochrane, he had given up his medical practice to his son Samuel on entering politics. In April 1834 and again in 1835 he advertised the resumption of his practice.

By 1835 partisan and sectarian feeling in St John’s had reached a fever pitch, with the two objects of popular animosity being Winton and Chief Justice Henry John Boulton*. In January, Carson began his four-year assault on Boulton in a speech in the house, and on 18 February he moved for a select committee to investigate alleged breaches by Boulton of the charter under which the new Supreme Court had been established. The motion was defeated, but in May, Boulton, in a city tense over the recent mutilation of Winton, gave Carson an opportunity to renew his attack. Without bothering to call a jury, Boulton sentenced Parsons of the Patriot to three months in prison and a fine of £50 for contempt. This action provoked Carson and Morris to establish a Constitutional Society, and a petition against Boulton, signed by 5,000 people, was presented in the House of Commons by O’Connell. Carson added to the atmosphere of crisis by writing an open letter to Boulton in the Patriot, in which he affirmed that the judge was “a fit object for censure and punishment.” (Boulton was in England and not expected to return.) When the tense summer was over and the colony was “subsiding into peace,” Carson wrote yet another inflammatory letter to the Patriot which well illustrates his instincts in politics. “Agitation must be kept up – the high spirits of a high-minded people must be cherished and supported,” he said. Political turmoil he welcomed as a sign of a country’s growing maturity. Of all the reformers in St John’s, he most closely resembled in temperament the rebels of Upper and Lower Canada.

In the general election of 1836, Carson, Kent, and Morris were successful in St John’s when their opponents withdrew. Moreover, despite a grand jury inquiry into outrages committed during the polling, and the even more dramatic development of an immediate new general election made necessary by a legal technicality discovered by Boulton, the reformers had won control of the house. For five years after the new session opened in July 1837, Carson would preside as speaker in one of the most combustible assemblies in the colony’s history.

Carson’s influence upon the house during this period is somewhat obscured by his position as speaker, but he undoubtedly countenanced the assembly’s assertiveness and helped to shape its initiatives behind the scenes. His influence may be detected in such moves as the attempt to undermine Edward Kielley*’s position as district surgeon, the awarding of an annual salary of £200 to the speaker, and the extreme step of having expunged from the journals the censure upon him of 9 May 1834. As for the principal obstinacy of the new house, its refusal to present supply bills incorporating changes by the Council, Carson made it clear to the governor that he supported the action. But perhaps his influence is most clearly seen in the assembly’s pursuit of Boulton, who had unexpectedly been confirmed as chief justice and had returned to Newfoundland. At the assembly’s first meeting on 3 July, Morris indicated that a committee of the whole would inquire into the administration of justice. Carson’s antipathy towards Boulton and general anxiety about fairness in the courts were sharpened by three cases in 1837. In the first, Carson, Morris, and others were charged with unlawful assembly, and Carson, deeply resentful, refused to appear in court until legally compelled. In May, during an action Carson took against McCoubrey, Boulton informed the jury that the phrase “mad Dr. Carson” was not a libel. A further humiliation occurred in Samuel Carson’s action against Kielley for defamation of character, also in May. In the course of this proceeding it was divulged that William Carson, to protect his son’s reputation, had entered the home of a female patient and, without authorization of any kind, conducted a painful, searching examination of the most intimate kind. On learning of this invasion of privacy, Boulton was so enraged that he rebuked Carson at length on the witness stand. It was not in Carson’s nature to submit to such treatment. In October the house petitioned the queen to recall Boulton, and when Carson left for England as a member of the assembly’s delegation to present this and other grievances to the British government, he told the public that his “sole purpose” was the removal of Boulton, “who ought never to have been permitted to contaminate our shores.” In July 1838 the judicial committee of the Privy Council recommended that it would be “inexpedient” that Boulton “should be continued in the office of Chief Justice of Newfoundland.”

Carson had arrived in London in January 1838 and on 19 February departed for Liverpool to visit his brother, leaving the work of the delegation to John Valentine Nugent*. He returned to St John’s in May. His visit to England having further stimulated his thinking on constitutional questions, he wrote letters to the Newfoundlander urging the assembly to “stick fast” to the principle that it should be modelled on the House of Commons. Carson himself adhered to the principle with great tenacity. On 9 Aug. 1838, acting on behalf of the assembly, he issued a warrant committing Kielley to jail for an alleged contempt of the house, uttered in the streets of St John’s. When Kielley was released on a writ of habeas corpus issued by assistant judge George Lilly, a similar warrant was issued for the arrest of the judge and the sheriff and, on 11 August, Lilly, who resisted arrest, was taken from the court-house to the home of the sergeant-at-arms. He was kept in custody for two days, whereupon Governor Henry Prescott* prorogued the legislature and set him free. When the house reopened on 20 August, Carson was presented with a writ by the sheriff on behalf of Kielley, claiming false arrest and placing damages at £3,000. Thus began the case of Kielley v. Carson, in which the issue was the assembly’s right to commit for contempt, a right Carson argued it possessed by reason of its analogy to the House of Commons [see Sir Bryan Robinson*]. The case went to the Newfoundland Supreme Court in December 1838, and a majority decision favoured the assembly, Lilly dissenting. Kielley gave notice of an appeal to the Privy Council. It would take over three years for the report of the judicial committee, reversing the decision, to be delivered.

The actions of the house in the Kielley affair provoked a flood of petitions to the British government calling for the abolition of the legislature and, together with the campaign against Boulton, solidified local mercantile feeling against the reformers. In 1838 the St John’s Chamber of Commerce forwarded a petition to the queen that linked “some of the leading members of our House” to the Canadian rebels and called for “an immediate abolition” of representative institutions. After the Supreme Court decision in the Kielley case, Carson gave notice that when the house reconvened he had “no doubt” it would want to consider whether the petition violated “its dignity and just privileges.” His letter – but one instance of Carson’s choosing to act, as speaker, independently of the legislature – amounted to a threat that John Sinclair, the chamber’s president, would be cited for contempt, a threat Prescott was not inclined to take lightly. There can be little doubt that the contentious activities of the house in the period 1837–39 helped to bring representative government into disrepute and paved the way for the Amalgamated Legislature. By his persistent assertion of the rights of the assembly, Carson was at least partly responsible for its diminishing reputation.

The years 1839–41 were to reveal divisions within the ranks of the reformers and bring new forces into play upon Newfoundland politics which tended to reduce Carson’s significance. The proceedings of the house show heated exchanges among Carson, Kent, Peter Brown, and Morris, and in the fall of 1839 Parsons began attacking the reformers in the Patriot and promoting responsible government. Carson was inclined to the view that “responsibility” had existed since 1833, an opinion Parsons scathingly rejected. But Carson persisted in his view that the constitution was “founded on a broad and liberal basis” and required only that members “put their shoulders to the wheel.” Parsons was also now advocating native rights, a growing movement in which Carson, for obvious reasons, could not take a deep interest. Early in 1840 the most serious rift in the reform party occurred when Morris and Carson parted company. Clearly the solidarity of the reformers was in jeopardy, and in the event no effective opposition was mounted by them to the constitutional experiment of 1842, in which the upper and lower houses were combined. Carson himself had been frustrated by the difficulties that the Council and other members put in the way of such improvements as the creation of a St John’s academy and the building of roads. In 1840 he called upon the people to “demonstrate, . . . petition” in order to preserve the assembly, but after eight years of representative government there no longer seemed to be support for such action.

In his 70th year Carson began the scientific study of agriculture, and this pursuit evidently occupied his attention more and more. It is possible that his large farm had already brought financial losses. But in agriculture Carson had found an interest which stirred him almost as much as constitutional rights. Letters on the advantages of pig farming, the preparation of compost, and the glories of the Rohan potato flowed to the press. Late in 1841 he became the first president of the Agricultural Society, and announced he would dedicate some of his leisure hours to “a few Lectures on agricultural subjects.” In June 1842 he presided at the first ploughing match ever held in Newfoundland; a month later he was fined for carting rotting cods’ heads. His agricultural interests had been encouraged by Sir John Harvey*, the only governor to succeed in overcoming Carson’s hostility to established authority. Despite the reservations of the Colonial Office, Harvey appointed Carson to the Council in September.

In December 1842 Carson was elected in St John’s, along with Nugent and Laurence O’Brien*. When the Amalgamated Legislature opened in January 1843, he unsuccessfully sought the speaker’s chair, losing to James Crowdy*, an appointed member. Carson soon recognized the weak position of elected members in the new system, and in February indicated that, “if his health will permit,” he would travel to England to petition against the election of Crowdy as “an uncalled for exercise of arbitrary power.” Thus his political principles held firm to the last. The night before he died, he called Parsons to his side, urging him to advocate a return to representative government and “to stir up the friends of the people.” According to Parsons, he had also sent for a Church of Scotland minister and relinquished his Socinian beliefs.

William Carson was a man of restless energy and driving ambition. There was in him an instinctive revulsion at the exercise of arbitrary power, together with an equally strong urge to confront such power, expose it, and defeat it. These were combined with a supreme confidence in the rightness of his own whig principles, a devastating frankness of expression, and a will of iron. When roused – and it did not take an alarming crisis to stir him – he was a formidable antagonist. He was by nature a partisan, was never inclined to compromise, and was prepared to follow his beliefs with absolute conviction into political action. He was the most radical and influential of the early Newfoundland reformers. As an agitator, he helped to undermine the ancient, paternalistic system of governing Newfoundland. As a propagandist, he disseminated views about its history, and about its potential for development, that would influence generations of writers and politicians. As a legislator, he tried to provide Newfoundland with useful social institutions and to preserve what he thought to be the rights and privileges of the House of Assembly.

William Carson is the author of three pamphlets, including A letter to the members of parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland . . . (Greenock, Scot., 1812), and Reasons for colonizing the island of Newfoundland, in a letter addressed to the inhabitants (Greenock, 1813); the third, on the subject of cholera, has not been located.

GRO (Edinburgh), Kelton, reg. of births and baptisms, 4 June 1770. PANL, GN 2/1, 20–45; GN 5/2/A/1, 1811–21; GN 5/2/B/1, 1819–20. PRO, CO 194/45–116; CO 195/ 16–20; CO 199/19. Univ. of Edinburgh Library, Special Coll. Dept., Faculty of Medicine, minutes of the proc., 1776–1811; Matriculation reg., 1786–1803; Medical matriculation index, 1783–90. Dr William Carson, the great Newfoundland reformer: his life, letters and speeches; raw material for a biography, comp. J. R. Smallwood (St John’s, 1978). Nfld., General Assembly, Journal, 1843; House of Assembly, Journal, 1833–42. Aris’s Birmingham Gazette; or the General Correspondent (Birmingham, Eng.), 1794–1808. Newfoundlander, 1827–43. Newfoundland Mercantile Journal, 1816–27. Newfoundland Patriot, 1834–42. Newfoundland Vindicator (St John’s), 1841–42. Patriot & Terra Nova Herald, 1842–43. Public Ledger, 1827–43. Royal Gazette and Newfoundland Advertiser, 1810–31. Gunn, Political hist. of Nfld.

Cite This Article

Patrick O’Flaherty, “CARSON, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 7, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carson_william_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carson_william_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Patrick O’Flaherty |

| Title of Article: | CARSON, WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | March 7, 2026 |