Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

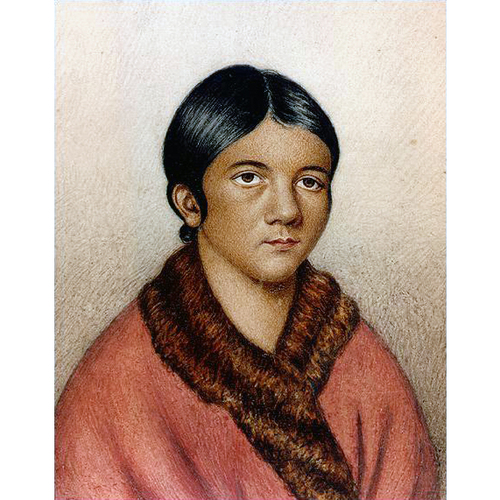

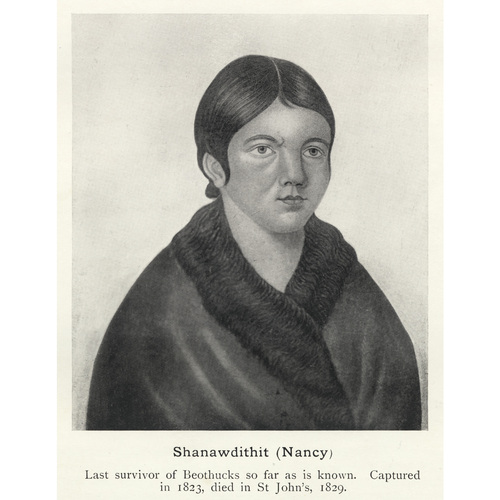

SHAWNADITHIT (Shanawdithit, Nancy, Nance April), Beothuk; b. c. 1801, daughter of Doodebewshet; d. 6 June 1829 in St John’s, Nfld.

Shawnadithit was the last known survivor of the Beothuk, the First Nations inhabitants of Newfoundland known to early European settlers as “Red Indians” for their use of ochre to colour their skin. A member of one of their small and rapidly dwindling family groups, Shawnadithit was the niece of Demasduwit* and her husband, Nonosbawsut. As a child and young girl she witnessed several of the final documented encounters between her people and white settlers, including both violent attacks and expeditions dispatched or authorized by the British and colonial officials to establish friendly relations; as a captive herself, she was the source of much of what is known about the customs, language, and last days of her people.

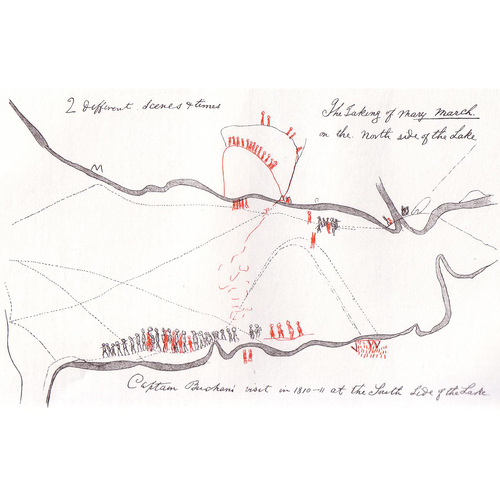

In January 1811 she was present at the meeting on the shore of Red Indian Lake with Lieutenant David Buchan* and his party, which ended in the deaths of two British marines. In the summer of 1818 she was with the Beothuk who scavenged goods from John Peyton Jr’s [see John Peyton] salmon boat and cargo at Lower Sandy Point, on the Bay of Exploits. She observed the kidnapping of Demasduwit and the killing of Nonosbawsut by Peyton’s party in March 1819 and witnessed the return by Buchan of her aunt’s body to the deserted encampment at Red Indian Lake in February 1820. In the spring of 1823 Shawnadithit, her sister, and their mother, Doodebewshet, weakened by starvation, were taken by the furrier William Cull at Badger Bay. Her father fell through the ice and drowned after what was reported to be a desperate attempt at rescue. Cull brought the three women to magistrate Peyton’s establishment at Exploits, on the more northerly of the two Exploits Islands, and Peyton himself sailed with them to St John’s by schooner in June. It was quickly decided by Buchan, acting in the absence but with the authority of the governor, Vice-Admiral Sir Charles Hamilton*, that the women should be returned to their people with presents as speedily as possible. In July Peyton left them at the mouth of Charles Brook with provisions and a small boat to make their way back to any survivors of their group. Unsuccessful, the three later returned on foot to the coast; the mother and sister, desperately ill, died within a few days of each another, and Shawnadithit was taken into Peyton’s household.

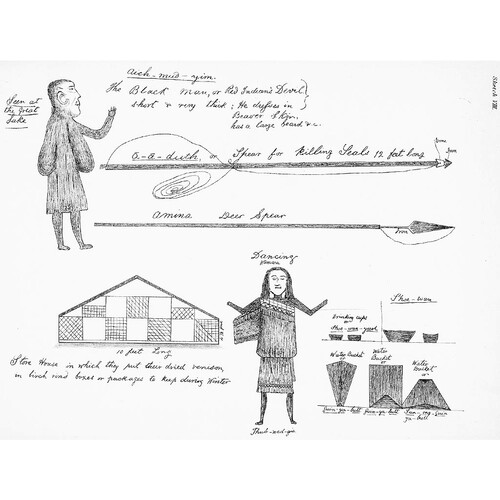

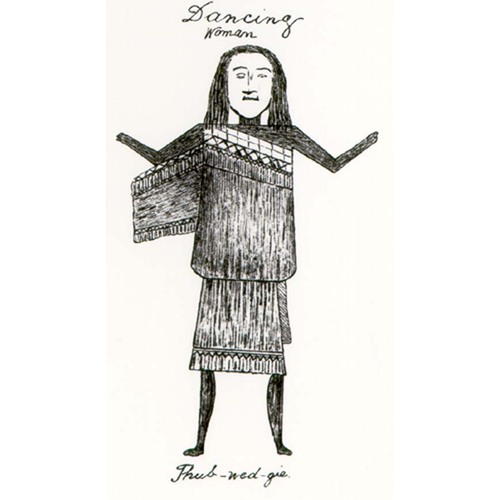

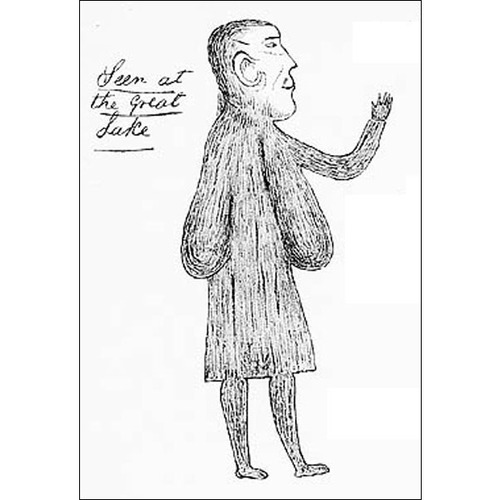

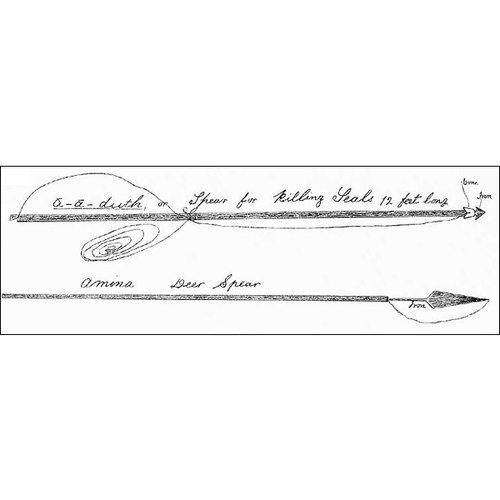

For the ensuing five years, Shawnadithit remained with his household at Exploits (not, as sometimes assumed, at Twillingate, to which he removed at a later date); she seems to have been kindly treated, despite Peyton’s previous violence towards the Beothuk. With the founding of the Boeothick (Beothuk) Institution by prominent citizens of St John’s and Twillingate, supported by interested patrons outside Newfoundland, she was brought to St John’s under the auspices of that organization in September 1828. There she resided with the president of the institution, William Eppes Cormack*, the peripatetic explorer, merchant, and philanthropist. It is to her that we owe credit for much of the data written down by Cormack: she is one of the prime witnesses to the Beothuk language, the customs of her people, and the events and general condition of the members in the final years when their numbers had fallen to perhaps less than 20. She was gifted with a pencil and sketch-book, and her drawings (frequently reproduced) are especially valuable. Moreover, as the last of her people, Shawnadithit has naturally figured largely in popular accounts.

The Beothuk were a small branch of the Algonkian people, and probably numbered fewer than 2,000 when Europeans first encountered them in the 16th and 17th centuries. They were hunters and fishers who depended largely upon the caribou of the interior in winter, and the fish and marine mammals of the coast in the warmer months. Aside from an account of their tentative meeting with John Guy*’s colonists in 1612, little is known about their contact with other indigenous people or their relations with Europeans until the last half of the 18th century. Before that time, the Beothuk seldom caught the attention of record-keeping white men, for the Europeans who went to Newfoundland did so to fish, not to convert First Nations to Christianity or to enlist their support in colonial wars, nor to trade with them for furs. Indeed, the Beothuk were unusual among the indigenous people of North America in that it was not always necessary for them to exchange furs or skins for highly valued manufactured goods. Newfoundland was a fishing colony above all else, and this fact meant that the seasonally vacant premises of migratory English fishermen were a rich source of iron tools, canvas sails, and the like. By the latter part of the 18th century, however, an increasingly permanent English resident fishery made it difficult for the Beothuk to scavenge from these installations without provoking a violent response.

There is little doubt that such violent retaliation contributed to the eventual extinction of these people. Yet a more important factor was the growth of a white population along the coast, which denied the Beothuk easy access to the marine resources upon which they were seasonally dependent. Archaeological work has suggested that by the end of the 18th century, the Beothuk had been forced to rely too much upon the resources of the interior, a difficult place to live, especially without firearms. If the Beothuk were malnourished as a result of increased dependence upon the meagre wildlife of the island’s interior, they would have been that much more vulnerable to European diseases, the great killers of all New World peoples. It is quite possible that this susceptibility, more than any other factor, was responsible for their doom. Indeed, historian Leslie Francis Stokes Upton has calculated that if the Beothuk experienced anything like the population decline suffered by indigenous groups elsewhere, their extinction could be explained solely as a result of loss through disease.

It was, however, the vivid accounts of fishermen and furriers murdering the Beothuk, not the Beothuk’s slow deaths from hunger and sickness, that finally attracted the attention of white authorities. In keeping with the growing humanitarian spirit of that age, a succession of Newfoundland governors, beginning in the 1760s with Hugh Palliser*, attempted to end settler attacks on the Beothuk and establish friendly relations with them. None of these efforts proved successful. The most promising of them, Lieutenant John Cartwright’s expedition to the Beothuk in 1768, in which his brother George Cartwright* was a participant, produced much information about their abandoned camps, but Cartwright met no Beothuk on his journey up the Exploits River. Unfortunately for generations of future historians, Cartwright also brought back rumours that Micmac (Mi’kmaq) from Nova Scotia were slaughtering Beothuk on a grand scale. There may have been occasional hostile encounters between Micmac trappers and Beothuk hunters, but the overwhelming weight of evidence suggests that, for the most part, they avoided each other. This, of course, was not the case with the Beothuk and the white population of the northern bays. In the face of official proclamations forbidding harassment of the Beothuk, fishermen and furriers continued to shoot or attempt to capture them, and the Beothuk continued to pilfer from European posts and even to kill the occasional white man.

This pattern continued in the 19th century with the additional development of a number of officially sponsored or encouraged attempts to kidnap Beothuk captives who would, it was hoped in St John’s, be employed as mediators between the two peoples. In 1803 this scheme produced one captive, a Beothuk woman with an unknown name, brought back to St John’s by William Cull. Governor James Gambier gave her presents and entrusted Cull with sending her back to her people, but as far as is known, this effort had no effect on Beothuk-settler relations. Subsequent Newfoundland governors also attempted to make peaceful contact with the elusive Beothuk, but it had become difficult, even dangerous, to approach these people, who by then had had several centuries of experience with ill-intentioned white men.

The most nearly successful attempt to establish contact occurred in the winter of 1810–11 when David Buchan and a small number of marines and settlers were sent up the Exploits River to Red Indian Lake by Governor John Thomas Duckworth*. Astonishingly, Buchan’s men succeeded in surprising a small bivouac of Beothuk, but he erred terribly in leaving two of his marines at the camp while he went back down the river to retrieve presents that he had left behind. When he returned, he found the headless corpses of his men and no Beothuk.

In the aftermath of the Buchan expedition Duckworth’s successor, Sir Richard Goodwin Keats, restated his predecessor’s warning that mistreatment of the Beothuk would be punished to the fullest extent of the law. And they needed protection: many of the fishermen and furriers of the Newfoundland coast saw the Beothuk not as heroic remnants of a persecuted people, but as dangerous thieves whose persistent forays threatened the lives and property of honest people. For their part, the Beothuk were caught in a cruel dilemma. Like many indigenous people they had grown dependent upon European materials, especially iron from which they fashioned spears, harpoon blades, arrowheads, and the like. Yet to acquire these things, they scavenged from coastal outposts and this routinely drew reprisals, such as the violence carried out by Peyton in March 1819 after he had lost £150 worth of gear.

It is now known that by the time of that raid, when Nonosbawsut was murdered and Demasduwit was seized, there were perhaps fewer than 20 Beothuk left alive – and fewer still by the time Shawnadithit was taken. They had been the victims of white society, to be sure, but they had not been – as many writers have alleged – hunted for sport and massacred in large numbers. They died off, as a people, because they were few in number to begin with, because they had no resistance to European diseases, and because Newfoundland was a fishing colony which, almost by definition, lacked enough of the sort of white men who wanted or needed to keep them alive. By 1827, when the Boeothick Institution was formed by Cormack and his handful of contemporaries, it was too late.

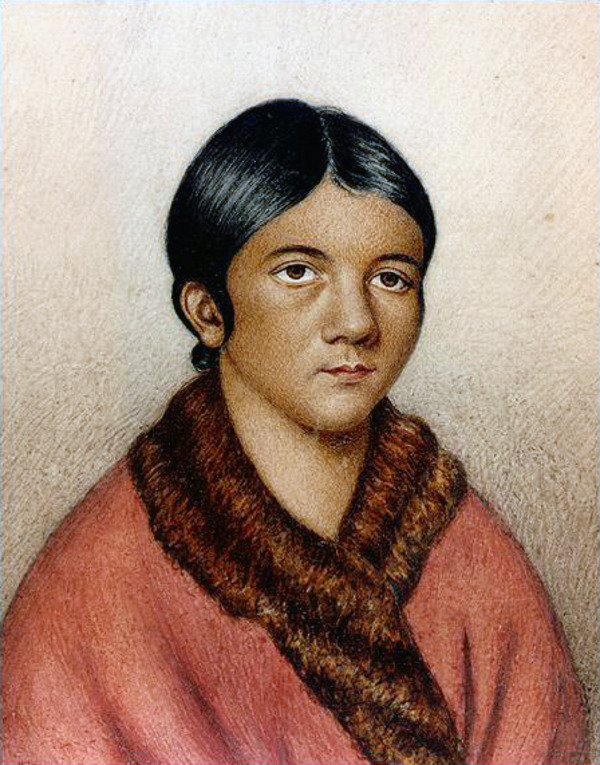

Shawnadithit remained in Cormack’s care until his departure from Newfoundland early in 1829; she was then transferred to the care of the attorney general, James Simms*. Her health, precarious for a number of years, continued to deteriorate, and she was seen a good deal during this period by William Carson*, who tended her in her last illness. She succumbed to tuberculosis on 6 June 1829 and was buried two days later in the military and naval cemetery on the south side of St John’s river-head, a site subsequently lost but approximately fixed by the unearthing of the remains of several military personnel under and adjacent to the Southside Road in November 1979. Carson’s description of her is brief but vivid. It was enclosed in a tin case with “the scull and scalp of Nancy Beothic Red Indian Female,” dispatched in November 1830 to the Royal College of Physicians of London, together with “answers to a series of sixteen questions”: “She was tall, and majestic, mild and tractable, but characteristically proud and cautious.” It is believed that the skull was lost during the Second World War. A monument to her memory stands somewhat to the east of the general site of her burial.

[The principal sources for our knowledge of Shawnadithit and her people are printed in Howley*, Beothucks or Red Indians, to which few documentary additions have since been made. In addition to important contemporary letters and manuscripts (many of which are preserved in the collections of the PANL), Howley printed a number of miscellaneous accounts that are of some value. The Pulling Manuscript (BL, Add. mss 38352: ff. 1–44) contains valuable information about relations between settlers and the Beothuk c. 1792. William Carson’s letter is at the PANL, GN 2/2, 17 Nov. 1830: 325–28. Archaeological work has been of the utmost importance; secondary sources include: Helen Devereux, “Five archaeological sites in Newfoundland: a description,” a report prepared for the former Nfld. Dept. of Provincial Affairs, now the Hist. Resources Division of the Department of Culture, Recreation, and Youth (2v., St John’s, 1969), and on file with the Nfld. Museum in St John’s; John Hewson, Beothuk vocabularies (St John’s, 1978); R. J. LeBlanc, “The Wigwam Brook site and the historic Beothuk Indians” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Nfld., St John’s, 1973); Don Locke, Beothuck artifacts (St John’s, 1974); Ingeborg Marshall, “An unpublished map made by John Cartwright between 1768 and 1773 showing Beothuck Indian settlements and artifacts and allowing a new population estimate,” Ethnohistory (Tucson, Ariz.), 24 (1977): 223–49; R. T. Pastore, “Newfoundland Micmacs: a history of their traditional life,” Nfld. Hist. Soc., Pamphlet ([St John’s]), no. 5 (1978); F. W. Rowe, Extinction: the Beothuks of Newfoundland (Toronto, 1977); Peter Such, Vanished peoples: the archaic Dorset & Beothuk people of Newfoundland (Toronto, 1978); J. A. Tuck, Newfoundland and Labrador prehistory (Ottawa, 1976); and L. F. S. Upton, “The extermination of the Beothucks of Newfoundland,” CHR, 58 (1977): 133–53.

Both Shawnadithit and her aunt Demasduwit, or figures suggested by them, have been used in the fiction and poetry inspired by the Beothuks. The earliest work of this kind is the novel Ottawah, the last chief of the Red Indians of Newfoundland; a romance, published anonymously in parts in London in 1848, but attributed in later editions to Sir Charles Augustus Murray (see E. J. Devereux, “The Beothuk Indians of Newfoundland in fact and fiction,” Dalhousie Rev., 50 (1970–71): 350–62). George Webber*’s long poem, The last of the aborigines: a poem founded in facts, was published in St John’s in 1851; there is an edition with introduction and notes by E. J. Devereux in Canadian Poetry (London, Ont.), no.2 (spring–summer 1978): 74–98. Other contributions to this continuing literature include Peter Such’s novel Riverrun (Toronto, 1973) and Sid Stephen’s Beothuck poems ([Ottawa], 1976).

The most authoritative discussion of the interrelated portraits of Shawnadithit and Demasduwit is by Ingeborg Marshall, “The miniature portrait of Mary March,” Newfoundland Quarterly (St John’s), 73 (1977), no.3: 4–7, supplemented by Christian Hardy and Ingeborg Marshall, “A new portrait of Mary March,” Newfoundland Quarterly, 76 (1980), no.1: 25–28. There is a modern portrait by Helen Shepherd (1951) displayed in the Nfld. Museum. r.t.p. and g.m.s.]

Revisions based on:

Ingeborg Marshall, A history and ethnography of the Beothuk (Montreal, and Kingston, Ont., 1996).

Cite This Article

Ralph T. Pastore and G. M. Story, “SHAWNADITHIT (Shanawdithit, Nancy, Nance April),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 9, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/shawnadithit_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/shawnadithit_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ralph T. Pastore and G. M. Story |

| Title of Article: | SHAWNADITHIT (Shanawdithit, Nancy, Nance April) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1987 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | March 9, 2026 |