Source: Link

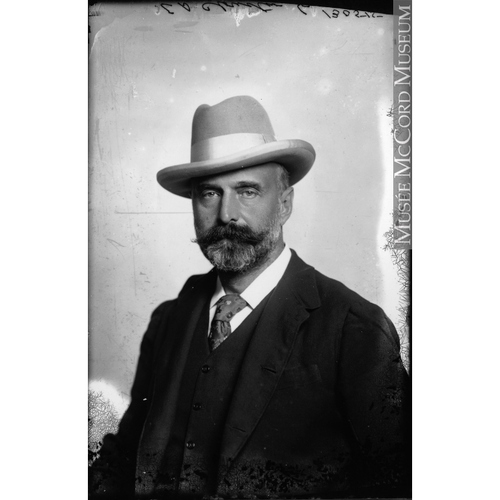

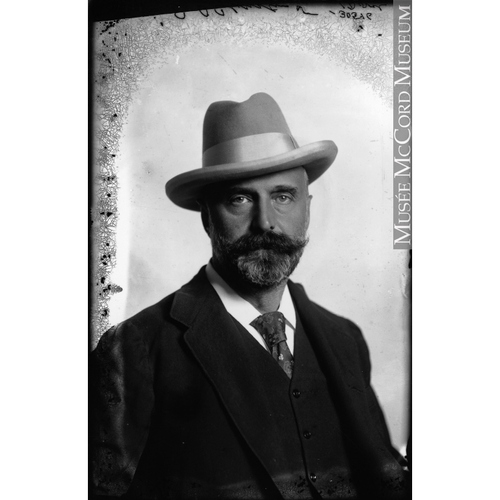

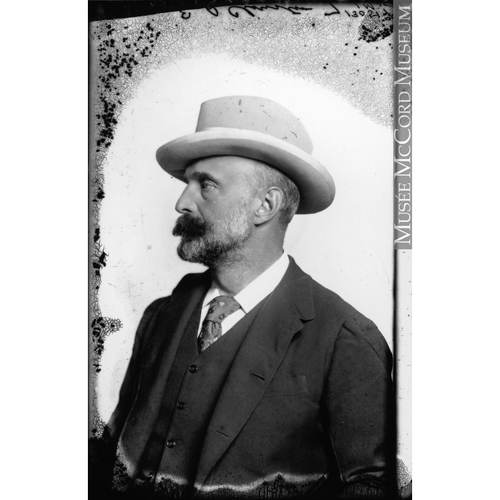

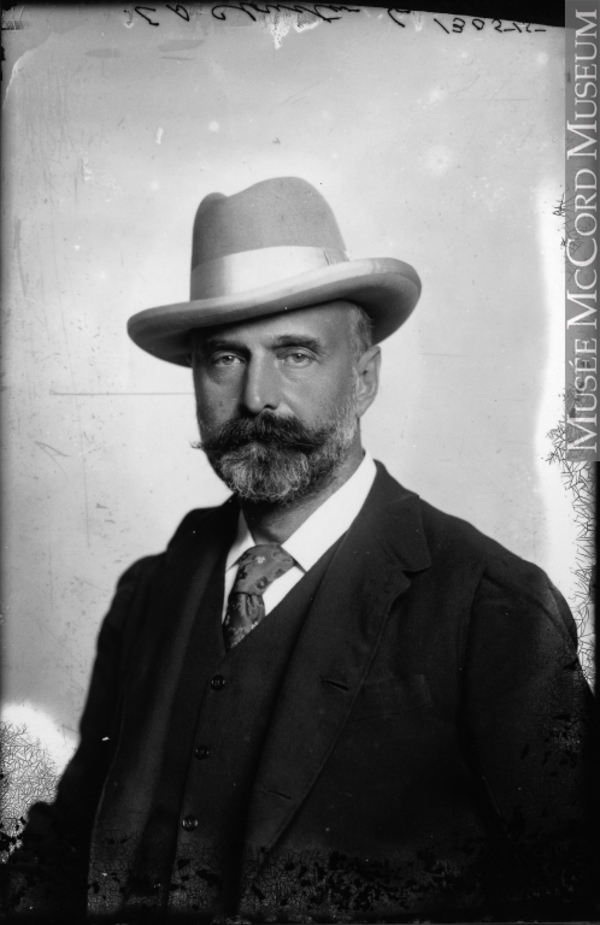

CLOUSTON, Sir EDWARD SEABORNE, banker; b. 9 May 1849 in Moose Factory (Ont.), son of James Stewart Clouston, a chief trader of the HBC, and Margaret Miles, mixed-blood daughter of Robert Seaborn Miles, a chief factor of the HBC; m. 16 Nov. 1878 Annie Easton in Brockville, Ont., and they had two daughters; d. 23 Nov. 1912 in Montreal.

Educated at the High School of Montreal, Edward Clouston began work for the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1864. On 8 March the following year he became a junior clerk with the Bank of Montreal, an institution in which his father held stock. Private and taciturn, known for his energy and his exacting and tactful manner, Clouston was marked for responsibility. In 1875, after several years in Brockville, Hamilton, and Montreal as an accountant, he was attached to the bank’s quarters in London, England, and the following year he joined its office in New York. In 1877 he was recalled to Montreal as assistant inspector.

In Montreal Clouston made the most of his experience and the support of two prominent men who would serve as vice-president and president of the bank, Donald Alexander Smith and George Alexander Drummond*. Smith, a friend of Clouston’s family, came to view the young man “like his son.” Their antecedents in the fur trade were similar and after Smith became Canada’s high commissioner in London in 1896 Clouston represented his financial and philanthropic interests in Canada. In 1879 Clouston became assistant manager of the bank’s Montreal branch and two years later he was appointed its manager. He was promoted assistant general manager of the entire bank in 1887, acting general manager in 1889, associate general manager in 1890, and finally general manager in 1891. Although his first years as general manager were marked by a number of fluctuations in international finance, shareholders continued to receive their 10 per cent dividend and the bank to consolidate its pre-eminence within Canada and to expand its activities abroad. Clouston held the post of general manager, for which he would eventually receive $35,000 annually, including benefits, until his resignation in December 1911. In 1905 he became a director and vice-president; he would retain these positions until his death in 1912.

Opposed to excessive competition within the Canadian banking community, in 1890 Clouston, along with Byron Edmund Walker*, Thomas Fyshe, and others, had organized the resistance of the chartered banks to the federal government’s proposed amendments to the Bank Act of 1871. One proposal required chartered banks to establish a circulation redemption fund, the size of which Clouston was able to limit. Having met on three occasions before making representations to the government, the leaders of the chartered banks had become sufficiently well organized to play an unprecedented role in drafting the legislation governing their own conduct. All their charters were renewed and the government’s proposed reforms, which had been backed by growing public demand, were emasculated.

The success of the banks’ concerted effort led to the foundation of the Canadian Bankers’ Association in December 1891. Clouston served a term as president the following year, and then sat on its executive council until he resumed the presidency in 1899, significantly on the eve of the decennial review of the Bank Act. He would retain the presidency until a week before his death. After its federal incorporation in 1900 the Canadian Bankers’ Association became a closed shop, with powers to control the redemption fund and to punish members who violated the association’s rules; in Clouston’s words, it became “an agent of government in administering the Bank Act.”

In January 1893 the Bank of Montreal, then twice the size of its closest Canadian competitor, replaced Baring Brothers and Company and Glyn, Mills, Currie and Company as the Canadian government’s agent in London, England. Three years later it also became the government of Quebec’s London agent. These lucrative agencies enhanced the Bank of Montreal’s international standing (during Clouston’s tenure it boasted of being the world’s third largest bank) and enabled it to tap and to direct the flow of British capital. They also augmented the bank’s influence on government policy; in fact, Clouston came to view his bank as Canada’s central bank and he plied political leaders with advice. His lectures to Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier on the need to reduce government expenditures, sell the Intercolonial Railway, and cease subsidizing other lines, especially those competing with the bank’s major client, the Canadian Pacific Railway, were not successful. Clouston railed frequently and publicly against Ontario premier James Pliny Whitney’s promotion of public ownership of the hydroelectricity generated at Niagara Falls.

Under Clouston’s direction, the Bank of Montreal expanded, largely through the absorption of existing banks. It acquired the Exchange Bank of Yarmouth in 1903, the People’s Bank of Halifax in 1905, and the People’s Bank of New Brunswick in 1907, and also assumed the assets of the bankrupt Ontario Bank in 1906 and some of those of the Sovereign Bank of Canada in 1908. Moreover, the Bank of Montreal continued to finance Canadian corporate expansion at home and abroad, especially in hydroelectric power, transportation, lumbering, and metallurgy with clients such as John Rudolphus Booth*, Edward Wilkes Rathbun*, the Laurentide Paper Company Limited, the Dominion Iron and Steel Company Limited [see Benjamin Franklin Pearson], and the Royal Securities Corporation Limited [see John Fitzwilliam Stairs*]. In addition, the bank purchased the bonds of American and Quebec railways.

The bank also promoted Canadian corporate interests abroad. In 1895 it became banker to the government of Newfoundland and was thereby committed to financing the Reid Newfoundland Company [see Sir Robert Gillespie Reid*] and the Dominion Iron and Steel Company Limited’s interest in iron ore from Bell Island. The bank became a partisan of the colony’s union with Canada.

With access to increasing pools of British capital as well as to technical and managerial expertise Clouston supported the financial cliques from Halifax, Toronto, and Montreal which set up various hydroelectric and traction companies in Latin America and the Caribbean and promoted Canadian investment in those regions. Under his direction the Bank of Montreal helped finance the Mexican Light and Power Company (of which Clouston was a leading shareholder, director, and in 1908–9 president) and its subsidiary, the Mexican Electric Light Company, as well as the Mexico Tramways Company, the Demerara Electric Company, and the Rio de Janeiro Tramway, Light and Power Company [see Frederick Stark Pearson].

The line Clouston and his colleagues drew between personal and corporate interests was an uncertain one. His position made him a useful, and often an automatic, corporate director, particularly of companies financed by his bank. Thus, he served as president, vice-president, or director of over 20 prominent firms. Nothing illustrates the potential conflict more dramatically than his involvement in the controversial attempt in 1908 to lease the floundering Mexican Light and Power Company, financed in part by the Bank of Montreal, to the Mexico Tramways Company, in which he had an interest. Normally what Drummond, the bank’s president, advised, Clouston endorsed, and vice versa; this issue, however, initially divided the two men, and also the Montreal business community. Clouston subsequently rallied to Drummond’s plan for defeating the proposal, but they lost control of Mexican Light to a group of Toronto, British, and American interests.

Although Clouston was reputed to have been a perceptive judge of character, his misguided confidence in the durability of the Mexican dictator, General Porfirio Díaz, and the stability of investments in the republic entailed considerable loss to the bank when Díaz was removed in the revolution of 1911. These losses, together with his handling of the Mexican Light and Power controversy, and his support of William Maxwell Aitken*’s part in pushing the Western Canada Cement and Coal Company (owned by Sir Sandford Fleming) into bankruptcy during the great merger which led to the creation of the Canada Cement Company in 1909, may have cost him the presidency of the bank and hastened his retirement. By 1910 he seemed to have lost the confidence of the board of directors. Contrary to public expectations, after five months of deliberation following Drummond’s death in February 1910 the board chose Richard Bladworth Angus* as president rather than the younger and more qualified Clouston. In November 1911 Clouston submitted his resignation; the public explanation was ill health. In return he received a year’s salary, the option of purchasing the general manager’s house for $100,000, and a retainer of $15,000 as long as he remained outside the service of another bank.

In civic affairs Clouston supported the formation of the Citizens’ League of Montreal and financed its campaign of 1909–10 to obtain a board of control for the city. Two years previously he had joined with other prominent businessmen to improve the city’s water supply and to provide more adequate fire protection for commercial property downtown. A vice-president of the Montreal Crematorium Limited and a life governor of the Montreal Protestant House of Industry and Refuge, he was also a benefactor of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, the University Settlement of Montreal, and the Boy Scout movement.

Despite his exacting business career Clouston was a keen sportsman, a good football, lacrosse, and racquet player, a snowshoer, fancy skater, curler, swimmer, yachtsman, golfer, and motorist. He belonged to at least 10 sports clubs and associations and held some executive positions. A trustee of the Stanley Cup, the Allan Cup, and the Minto Cup, he donated a cup to the Montreal Horse Show and a trophy to the Royal Life Saving Society to encourage competitive swimming. As a director and vice-president of the Parks and Playgrounds Association of Montreal, Clouston, with his wife (who was vice-president of the ladies’ committee), took an active part in the preservation of Mount Royal Park.

Clouston was generous in his support of health services. He served as governor (1893–1912) and president (1910–12) of the Royal Victoria Hospital and as governor of six other hospitals in the Montreal region. He was an executive member of the St John Ambulance Association and sat on the provincial council of the Red Cross Society. He was also a benefactor and president of the Montreal Association for the Blind.

Like many of Montreal’s merchant princes, Clouston supported education, and was a patron of theatre, music, art, and libraries. He was a governor of the Fraser Institute and of McGill University and a member of the Champlain Society. A benefactor and councillor of the Art Association of Montreal, he possessed “many fine pictures” and donated the stained glass windows for the Royal Victoria Hospital’s chapel.

A staunch imperialist, Clouston persuaded the bank to make generous and unprecedented contributions to South African War charities and in 1909 promoted the creation of an imperial press service. Described by the Star (Montreal) in 1907 as a millionaire, Clouston was created a baronet in 1908 and sought and received a coat of arms from the College of Arms in England. He and Lady Clouston entertained lavishly at their Montreal residence and at Boisbriant, their 300-acre estate at Senneville, a property evaluated at $35,000 in 1898. At Boisbriant Clouston could indulge his interest in horse breeding, fruit growing, and horticulture. He was a director of the Montreal Horticultural Society and Fruit Growers’ Association of the Province of Quebec.

Clouston’s sudden death was announced across Canada and in the United States and Great Britain. At St Peter’s Church, Eaton Square, in London, a memorial service was attended by Lord Strathcona [Smith], former governors general, and numerous titled friends and associates. Although his funeral in the Church of St John the Evangelist in Montreal was private and unostentatious, it was attended by the city’s corporate and political élite.

Described as the epitome of Canadian banking, Clouston was shrewd, powerful, and austere, although far from cautious or conservative in financial matters. A thinker and a listener, he surrounded himself with strong, loyal men resembling himself. He was hailed as a patron of arts and letters, a patriot, and a benevolent and generous employer, particularly considerate of his employees. Given his reputation as a man of few words, the Canadian Bankers’ Association felt that silence was “the most fitting tribute to his memory.” Until he receives the major biography he deserves, questions on his life and career will remain unanswered.

AO, RG 80-5-0-73, no.5506. McCord Museum of Canadian Hist. (Montreal), Clouston family papers. NA, MG 27, II, B1. Gazette (Montreal), 16 April 1908, 25 Nov. 1912. Montreal Daily Star, 25 Nov. 1912. Christopher Armstrong and H. V. Nelles, Southern exposure: Canadian promoters in Latin America and the Caribbean, 1896–1930 (Toronto, 1988). W. H. Atherton, Montreal, 1534–1914 (3v., Montreal, 1914). Bank of Montreal, List of stockholders of the Bank of Montreal . . . , 1862–1909. B. H. Beckhart et al., The banking system of Canada (New York, 1929). The book of Montreal; a souvenir of Canada’s commercial metropolis, ed. E. J. Chambers (Montreal, 1903). Canadian annual rev. (Hopkins), 1907, 1909. Canadian Bankers’ Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 7 (1899–1900): 383; 8 (1900–1): 120; 19 (1912–13): 118–19; 20 (1913–14): 89–90. “Canadian celebrities: Mr E. S. Clouston,” Canadian Magazine, 12 (November 1898–April 1899): 434–36. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). The centenary of the Bank of Montreal, 1817–1917 (Montreal, 1917). Merrill Denison, Canada’s first bank: a history of the Bank of Montreal (2v., Toronto and Montreal, 1966–67), 2. D. S. Lewis, Royal Victoria Hospital, 1887–1947 (Montreal; 1969). R. T. Naylor, The history of Canadian business, 1867–1914 (2v., Toronto, 1975), 2.

Cite This Article

Carman Miller, “CLOUSTON, Sir EDWARD SEABORNE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/clouston_edward_seaborne_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/clouston_edward_seaborne_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Carman Miller |

| Title of Article: | CLOUSTON, Sir EDWARD SEABORNE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |