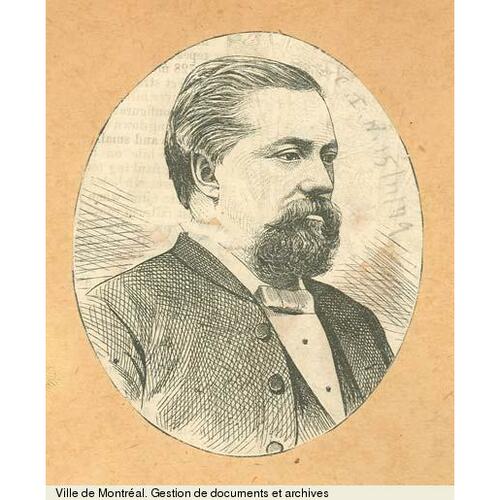

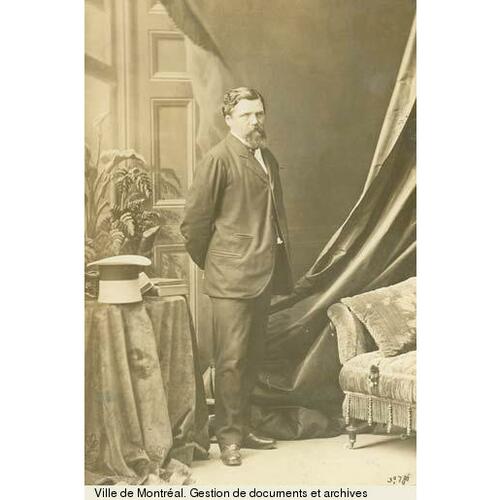

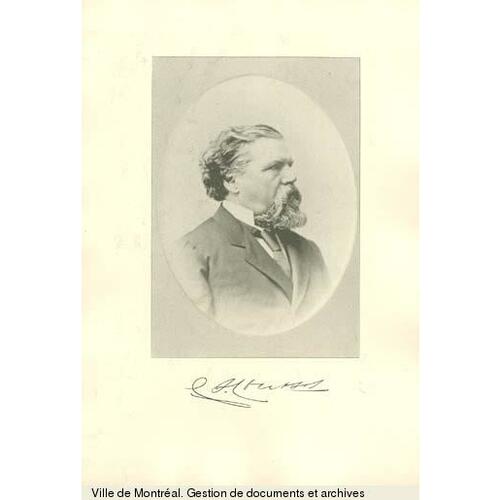

COURSOL, CHARLES-JOSEPH (baptized Michel-Joseph-Charles), lawyer, office-holder, politician, and businessman; b. 3 Oct. 1819 at Fort Malden, Amherstburg, Upper Canada, only child of Michel Coursol and Mélanie Quesnel; m. 16 Jan. 1849 at Montreal, Émilie-Hélène-Henriette, daughter of Étienne-Paschal Taché*, and they had two sons and two daughters; d. 4 Aug. 1888 at Montmagny, Que.

Charles-Joseph Coursol’s father, who died the year after the birth of his son, was an officer with the Hudson’s Bay Company stationed at Fort Malden. Charles-Joseph was subsequently adopted by his uncle, Frédéric-Auguste Quesnel*, and enjoyed a comfortable upbringing in Montreal; he was also to share with his cousin the considerable fortune left by Quesnel on his death in 1866. From 1828 to 1834 he was educated at the Petit Séminaire de Montréal and later studied law with Côme-Séraphin Cherrier, a prominent member of the Viger–Papineau family who became his stepfather in 1833.

Although Coursol apparently took no part in the rebellions of 1837–38, by the time he was called to the bar on 24 Feb. 1841 the cause of reform, coalescing in Canada East around Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine*, had seized the youth with, as one contemporary, John Fennings Taylor, claimed, “the violence of a moral epidemic.” His early political career, whether as the leader of a mob of 600 bludgeon-armed toughs supporting Reform candidate James Leslie* in Montreal during the election of March 1841, or as a defender of La Fontaine’s Montreal home in August 1849 from a Tory mob enraged by the Rebellion Losses Bill, suggests he was attracted by the more physical, organizational side of the struggle for responsible government.

An extroverted, passionate activist, related both by birth and by marriage to notable families in the province, Coursol moreover acquired a distinguished legal reputation. As a consequence he won local popularity and secured election as a city councillor for Saint-Antoine Ward from 1853 to 1855. The same attributes had made possible for Coursol the more propitious rewards of patronage from the ministry of La Fontaine and Robert Baldwin* and later of Taché and Sir Allan Napier MacNab*. On 30 June 1848 he was appointed coroner, with Joseph Jones, for the district of Montreal; in January 1856 he was commissioned a captain in the 2nd Company of Militia Cavalry, Montreal; and, most important, on 2 Feb. 1856 he was named inspector and superintendent of police for Montreal: by virtue of this last appointment he also served as chairman of the quarter sessions and judge of the sessions of the peace for the district.

Toward the end of the American Civil War, Judge Coursol severely aggravated the already poor relations between the United States and Canada with a decision which was one of the factors in the abrogation of the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854. On 19 Oct. 1864 a group of about 20 Confederate soldiers, who had gathered in Canada East, launched an attack on the border town of St Albans, Vt, looting and firing it. Pursued back across the border by a local posse, 14 of the raiders were arrested by Canadian authorities and were held in Saint-Jean (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu) on six charges of extraditable offences. Coursol was sent from Montreal to act as the presiding magistrate when the preliminary examinations opened in the last week of October. Shortly after the trial began, Coursol changed the venue to Montreal. On 13 December, after a prolonged trial, he discharged the prisoners and most of them fled the country. Ignoring the question of the legal status of “raiders” under British law, and without referring the case either to the attorney general for Canada East, George-Étienne Cartier*, or to a higher court, Coursol, “this wretched prig of a police magistrate” (in John A. Macdonald*’s view), argued that he lacked the jurisdiction to pass judgement owing to the fact that the Canadian extradition act of 1861 had not been proclaimed by the British parliament. Coursol, however, was in error, the act having indeed been recognized in England by an order in council. The governments of the two countries were outraged. He was suspended from the office of police magistrate on 26 Jan. 1865. The report of the commissioner in charge of the inquiry into the proceedings connected to the raid, Frederick William Torrance, found Coursol, as a servant of the crown, liable to an indictment “for malfeasance” in office. Nevertheless, on 9 April 1866, after tensions and memories had faded, Coursol was reinstated at the urging of Cartier on the grounds that the error had been made in good faith: a politically astute decision.

Throughout the 1860s and 1870s Coursol’s continued interest and participation in a wide variety of Montreal’s cultural, social, and business affairs increased his popularity. A director of the Banque du Peuple and president of the Crédit Foncier du Bas-Canada, he found the time and enthusiasm during the Trent crisis of 1861 to raise a militia regiment, the Canadian Chasseurs. As lieutenant-colonel, he commanded the unit along the Canadian-American border during the Fenian threat of 1866. Three years later Coursol received two federal appointments: police commissioner for the dominion and commissioner under the Canadian statute of 1868 concerning the extradition provisions of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842. His local aspirations peaked when he was elected mayor of Montreal by acclamation in 1871 and again in 1872, followed by four consecutive terms, 1872–76, as president of the Association Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal. On 24 June 1874 the association held the largest demonstration ever seen in the city to that date in an attempt to encourage the repatriation of French Canadians who had gone to live in the United States [see Ferdinand Gagnon]. Coursol was a member of the Montreal Harbour Commission from 1871 to 1873 and was also prominent in the movement organizing the Papal Zouaves [see Ignace Bourget]. He was created a knight of the Order of Charles III of Spain in 1872 and on 28 February of the following year was named a qc.

Not surprisingly, in the second half of the 1870s, while the federal Conservatives regrouped to assault Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie*’s Liberal government, the Montreal Tory organization viewed Coursol favourably although perhaps as a somewhat unreliable ally. “He is desperately ambitious,” wrote Thomas White to Macdonald, “and that trait in his character is one to play upon.” Sir John was urged to dangle vague promises of political preferment before him. Whatever stratagem Macdonald used, Coursol, championing the National Policy, won the constituency of Montreal East by almost 1,400 votes in the general election of 1878. In the next contest of 1882 he won the seat by acclamation. However, the North-West rebellion of 1885, and possibly his disappointed aspirations for a seat in the Senate, led him and several others in March 1886 to break Conservative ranks to support the motion made by Auguste-Charles-Philippe-Robert Landry* deploring the government’s stance on the hanging of Louis Riel. In the subsequent election of 1887, Coursol, “an old Conservative” and still a supporter of the National Policy, accused the Conservative party of having betrayed its duty and traditions, and ran as an independent Conservative. The party members recognized the hopelessness of opposing the popular renegade and did little to dramatize his disaffection while the Liberal press supported him as an oppositionist. On 15 Feb. 1887 he again won by acclamation. He died 18 months later, having taken little part in the parliamentary session.

AC, Montréal, État civil, Catholiques, Notre-Dame de Montréal, 7 août 1888. PAC, MG 24, B125; MG 26, A, 19, 203, 296, 434; MG 30, D1, 9: 112–18. [J. A. Macdonald], Correspondence of Sir John Macdonald . . . , ed. Joseph Pope (Toronto, 1921), 19. Canada Gazette, 1 July 1848; 19 Jan., 2 Feb. 1856; 4–5 Dec. 1869. Gazette (Montreal), 28 Jan. 1856, 5 Sept. 1865, 17 Feb. 1887, 6 Aug. 1888. La Minerve, 6 août 1886, 16 févr. 1887. Montreal Herald and Daily Commercial Gazette, 15, 16 Feb. 1887; 6 Aug. 1888. Canadian directory of parl. (J. K. Johnson), 139. CPC, 1887: 198. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose, 1886), 665. Notman and Taylor, Portraits of British Americans, II: 325–28. Wallace, Macmillan dict., 157. Creighton, Macdonald, old chieftain, 448–49; Macdonald, young politician, 195; Road to confederation, 212. Histoire de la corporation de la cité de Montréal depuis son origine jusqu’à nos jours . . . , J.-C. Lamothe et al., édit. (Montréal, 1903), 210–11, 291–93. Monet, Last cannon shot, 75, 131, 241, 342. P.-G. Roy, La famille Taché (Lévis, Qué., 1904), 41, 56–57, 61–62. Rumilly, Hist. de Montréal, III. L. B. Shippee, Canadian-American relations, 1849–1874 (New Haven, Conn., and Toronto, 1939). Léon Trépanier, “Figures de maires,” Cahiers des Dix, 22 (1957): 163–92.

Cite This Article

Lorne Ste. Croix, “COURSOL, CHARLES-JOSEPH (baptized Michel-Joseph-Charles),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 9, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/coursol_charles_joseph_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/coursol_charles_joseph_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Lorne Ste. Croix |

| Title of Article: | COURSOL, CHARLES-JOSEPH (baptized Michel-Joseph-Charles) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | March 9, 2026 |

![Feu l'honorable Michel-Joseph-Charles Coursol [image fixe] / William Notman et Armstrong Original title: Feu l'honorable Michel-Joseph-Charles Coursol [image fixe] / William Notman et Armstrong](/bioimages/w600.4573.jpg)