MACKENZIE, ALEXANDER, stonemason, businessman, militia officer, journalist, politician, and author; b. 28 Jan. 1822 in Logierait, Perthshire, Scotland, son of Alexander Mackenzie and Mary Stewart Fleming; m. first 28 March 1845 Helen Neil (d. 1852) in Kingston, Upper Canada, and they had two daughters, one of whom died in infancy, and a son, who also died as a child; m. secondly 17 June 1853 Jane Sym; they had no children; d. 17 April 1892 in Toronto and was buried in Sarnia.

Alexander Mackenzie was the third of ten sons, three of whom died as infants. The family was not well off, as frequent moves, from Logierait to Edinburgh and then in turn to Perth, Pitlochry, and Dunkeld, attested. Mackenzie’s father was trying to improve his job prospects through these moves. He had done well as a carpenter during the high employment of the Napoleonic Wars; perhaps this success had expedited his marriage in 1817. However, employment and wage expectations had declined thereafter and by the 1830s his health was precarious. His death in 1836, at the age of 52, made the family’s position difficult. Yet the steady industry of the three elder sons, Robert, Hope Fleming, and Alexander, positioned the family sufficiently well to obtain sensible apprenticeships for them. Alexander began working full-time at age 13, during his father’s last year; he was apprenticed as a stonemason at 16 and began work as a journeyman less than four years later.

Mackenzie’s deep sense of familial attachment was clear in both his early labours to garner income and, when he left home job hunting at 19, his quick adoption of a surrogate family in Irvine, the Neils. His attachment to them was strengthened by his affection for one of the daughters, Helen, who in 1845 would become his wife. He found it attractive to emigrate to the Canadas with this family in 1842, arriving in May “with scarce 16 shillings in my pocket.”

To some degree Mackenzie and the Neils had fallen victim to roseate talk about the employability and high wages of stonemasons in the New World. Though Mackenzie was offered a job at Montreal, he and the Neils chose to move on to Kingston, where, it was rumoured, better pay was available. This mistaken notion, and rock that was too hard for his tools, inadvertently set the footings for Mackenzie’s business career as a general builder and building contractor. His ability to learn new skills quickly and his firm, direct way of handling workers rapidly enhanced his reputation. Over the next several years he served as a foreman or contractor on major canal and building sites in Kingston, St Catharines, and Montreal. A serious injury kept him out of work for nearly two months in 1844, but he was sustained in his positive outlook by his elder brother Hope, a carpenter-cabinetmaker who had come to Canada on Alexander’s invitation in 1843. In 1846 Hope chose Port Sarnia (Sarnia), in Upper Canada, as the site where the whole family could settle; Mary Mackenzie and her remaining sons immigrated the following year. The family, so central to Mackenzie, was whole again.

Mackenzie now engaged in a successful career constructing public buildings and houses in the southwest part of the province and took on ancillary work as a developer and as a supplier of building materials. His construction included the Episcopal church and the Bank of Upper Canada in Port Sarnia and court-houses and jails in Sandwich (Windsor) and Chatham. Several of his brothers were involved with him in this activity and it assured him of prosperity. In 1859 Mackenzie, his brother Hope, contractor James Stewart, and Kingston plumber Neil McNeil submitted losing bids on the construction of the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa [see Thomas Fuller].

A firm Victorian piety complemented Mackenzie’s attachment to family and the perspectives of his trade. Though born into a strongly Presbyterian family, at the age of 19 or 20, not long after he had left his family home, he found Baptists more attractive. Religious belief meant more to Mackenzie than institutional attachment, pious rhetoric, or a structure of acceptable moral norms. The afterlife was an ever-present reality, as his later letters to his second wife and to his daughter bear witness. He was widely considered to be honest and frank to a fault. His religious belief gave him a sense of strength and comfort which sustained him in periods of great stress.

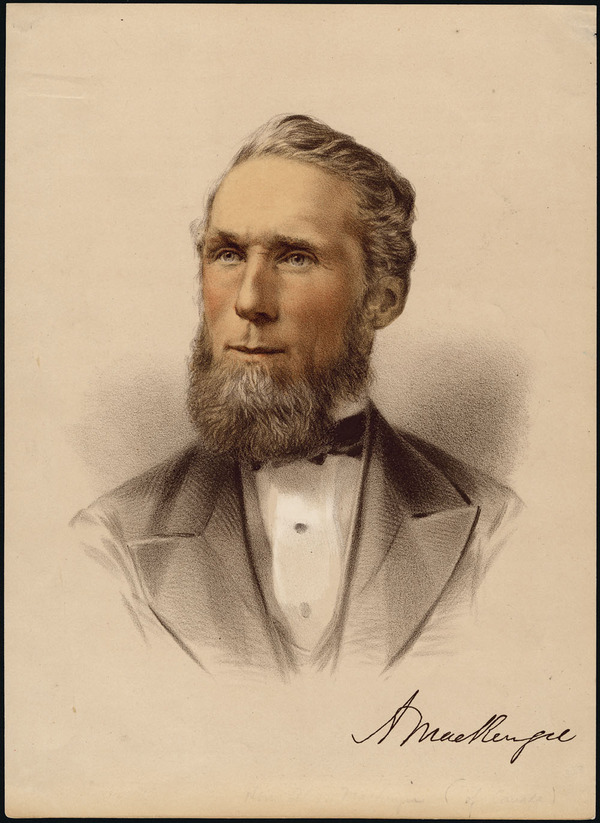

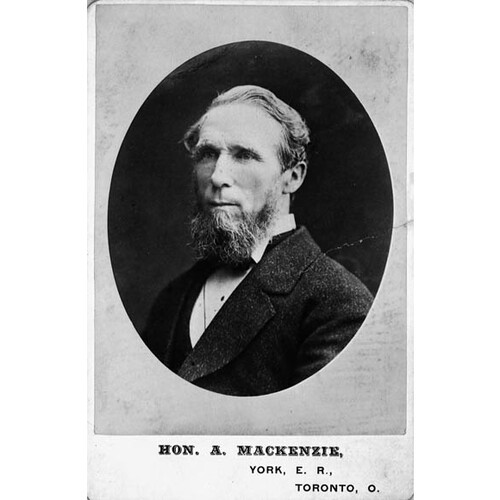

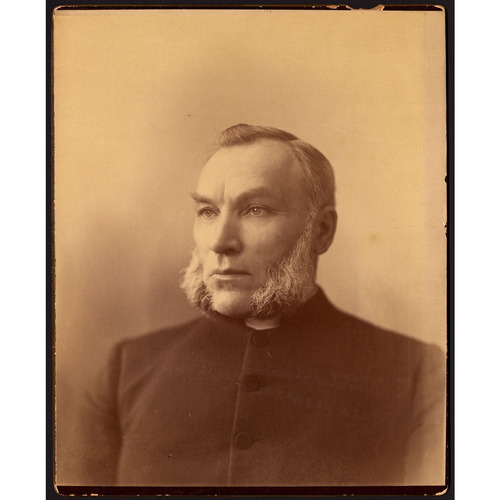

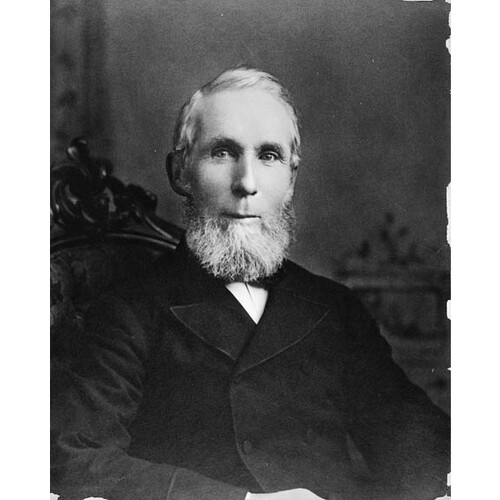

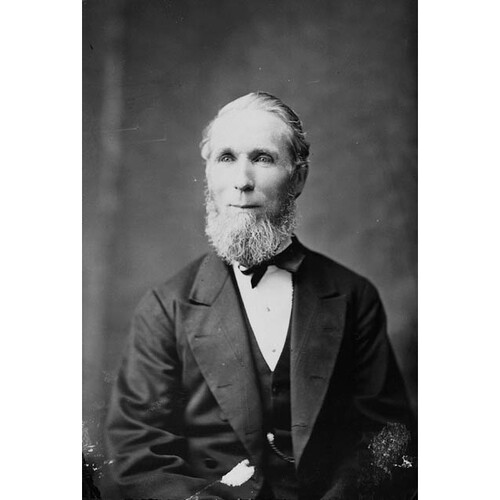

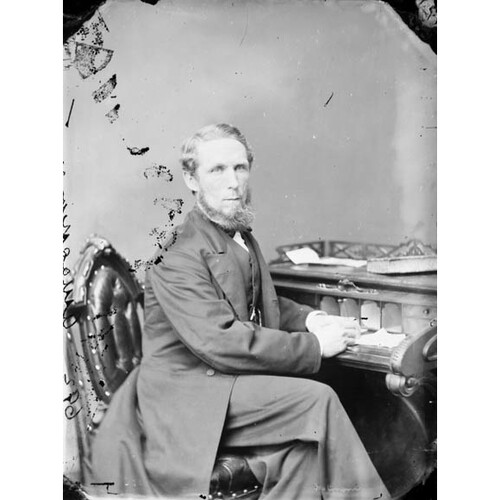

Mackenzie’s early introduction to the work world, his fierce commitment to the well-being of his family, and his religious background and convictions, indeed his Scottish culture, made him utilitarian. Even in maturity, he found little use for frivolous pursuits: he complained in a world-weary way to his wife in 1879 about the fuss people made over Edward Hanlan*’s latest rowing victory, which he termed an “utterly useless trial of strength.” Had the test been “cutting and splitting wood, hoeing corn, ploughing or any other useful occupation which would be of general benefit to mankind, I could have some sympathy with the excitement.” None of his contemporaries disputed the diligence with which Mackenzie pursued what he conceived to be his duty. Photographs of the man show an austere face, sharp eyes, and a tight mouth. He combined a physically compact frame with slightly reddish hair and a weather-beaten face. He did not dress well, most obviously at the beginning of his career in federal politics. This lack of sartorial concern reflected not only his utilitarian outlook but also his constant sense of personal budgetary constraint. In 1876, when he was prime minister, he lamented having to spend $128 for a politically necessary banquet and noted that he was avoiding entertaining on the score of cost. Here was the personal corollary of the political reformer’s emphasis on financial retrenchment.

In public addresses and in frequent speeches in parliament, Mackenzie spoke extemporaneously, with only the briefest jottings to support him. He rooted his speeches in factual material culled through a voracious reading of newspapers, government documents, biography, and history, and they were delivered with a noticeable Scottish burr. Their occasional literary adornment did nothing to disguise a style both vigorous and acerbic. William Buckingham, Mackenzie’s secretary during his prime ministership and his biographer, noted in retrospect that his humour wounded rather than healed.

Mackenzie had, in common with a wide range of other Reformers and Liberals, a consistent and relatively well-defined body of ideas: 19th-century liberalism. His egalitarianism was a deeply ingrained belief. He had absorbed some of his notions about equality from the meetings of moderate Chartists he attended when he was 19 and 20. Emigration to Canada enhanced and confirmed these views. Soon after he arrived in 1842, he engaged in lively political discussions in which he attacked the established position of the Church of England in Upper Canada. Established churches were symbols of the institutionalization of privilege, and meant, as was the case with the Roman Catholic Church in French Canada, a loss of individual freedom of choice. His ideal was the separation of church and state. Responding to celebrations in Scotland in 1875 of his prime ministership, he compulsively mentioned Britain’s established church and its rigid class structure, though in his speeches on this visit he played down his dislike of each for obvious political reasons.

The potential for social and economic mobility offered by the Canadas appealed to his liberal economic notions and became part of his conceptual landscape. Like other Reformers, Mackenzie did not see enormous disparities of wealth and status in post-confederation Canada. The agrarian society of Ontario approached the ideal of Mackenzie and the Reformers because of the large number of hardworking, independent farmers, purportedly beholden to no one but themselves for their success and free of the strictures imposed on wage-earning classes. The Reformer in Canada should attempt to ensure the mobility of goods, labour, and capital nationally and internationally, and to prevent the development of institutionalized distinctions which limited the freedom of individuals, retarded their economic progress, and caused conflict between social groups. Indeed, these attitudes were reflected in the Reformers’ horror at both the Pacific Scandal and the class privileges they felt were associated with the protective tariff imposed by the Conservatives in 1879. The legislation introduced by Mackenzie’s own government was frequently marked by this ideological thrust.

Mackenzie was involved in politics in Canada from virtually the time he arrived. By late 1851, at Port Sarnia, he was a key Reformer, his position having evolved into secretary of the Reform Association of Lambton County. In September 1851 the Reformers of Lambton and Kent asked George Brown*, the politically active owner-editor of the Toronto Globe, to oppose Arthur Rankin, a candidate supported by Malcolm Cameron*, a Reformer of a ministerialist stripe, in the riding of Kent in the forthcoming general election. Mackenzie widened his political scope by campaigning strenuously, with Archibald McKellar and others, to obtain the nomination for Brown and then by helping bring about his election to the provincial assembly in December 1851. The basis of Mackenzie’s own political career was laid.

When Brown ran in Toronto in the general election of 1857–58, Hope Mackenzie, not Alexander, took the Reform nomination in Lambton. Perhaps Alexander felt that his political reputation had been permanently besmirched by a libel suit that Cameron had brought against him in 1854. An editorial in the Lambton Shield, which Mackenzie had been carrying in editorial and financial terms from 1852, had suggested that Cameron had been involved in a clear-cut case of corruption. Mackenzie lost the suit, had to meet court costs and a £20 award, and, because of the financial pressure, was forced to close the newspaper. The case certainly brought him his first moments of political loneliness.

Hope was defeated by Cameron, but when Cameron moved on to the Legislative Council in 1860, Hope ran successfully in the Lambton by-election. He refused to run in the general election of 1861. There was a strong move to Alexander, whose activity as a census taker and as a member of Port Sarnia’s fire brigade, temperance society, Dialectic Society, and school board had broadened his knowledge of the community and enhanced his reputation. He was duly elected and represented Lambton in the provincial assembly until confederation.

Alexander Mackenzie established himself as a man of direct expression and forceful opinions. He developed a strong sense of parliamentary tactics, which later stood him in good stead. A companion-in-arms of George Brown, the Reform leader, he held views on representation by population, retrenchment and fiscal responsibility, the supremacy of parliament, and church-state relations that followed predictable paths, informed as they were by his egalitarianism, his economic liberalism, and his suspicion of unreasoned institutional authority. Yet his beliefs on such matters could be compromised when the special interests of his constituency or region were at stake. In the 1860s, for example, he lobbied for the oil-producers of southwestern Ontario, gaining lower excise taxes for them, which effectively increased the tariff protection they already had.

A crisis in the Reform movement qua party would come with confederation. It was widely believed that confederation solved the range of political issues over which party divisions had taken place: the old political parties thus no longer had any purpose. A fusion government was now required to pursue new and compelling national aims. The making of the “Great Coalition” in 1864, into which Brown had taken most Reformers, with Conservatives, to bring about confederation, was seen as evidence of the propriety of the trend. This powerful argument, however, brought many Reformers to disagreement with their erstwhile party. Mackenzie had denounced the trend. Though he was one of Brown’s most loyal followers and spoke in favour of confederation, he publicly expressed strong reservations about the formation of the “Great Coalition.” Coalition involved compromising Reform principles. It weakened and divided the party, Mackenzie urged. He opposed anti-partyism because he believed parties to be intrinsically necessary to the political system, and because some issues, particularly those of parliamentary supremacy and fiscal responsibility, remained outstanding.

Brown had helped fashion a Reform or Liberal party that was explicitly regional and sectional, and therefore would not easily develop national alliances once confederation was in place. He had striven for more than a year after his resignation from the coalition cabinet in December 1865 to create a Liberal opposition with national aspirations but he chose to give up elective politics in 1867. Liberals were left without a clear leader, only with a leadership group drawn from Ontario and Quebec: Edward Blake*, Luther Hamilton Holton*, Antoine-Aimé Dorion, and Mackenzie.

For a party that had roots in sectionalism and religious and ethnic hostility, anti-partyism and the loss of Brown were sharp blows. But the problems of constructing a national party were not these alone. The behavioural norms of the parliamentary Reform party were individualist and only loosely fraternal. Thus, while Mackenzie, who was elected for Lambton in 1867, openly performed the functions of a party manager in the House of Commons after confederation, he did not have any associated authority. His managerial role was likely a result of his reputation as a Reform purist and loyalist, a reputation compounded from his organizational activity, his diligence, his ideological commitment, and his identification with Brown. Only a safe man like Mackenzie could be entrusted with fostering a national party while keeping in check not only the leadership ambitions of unevenly talented men such as Holton but his own. At best Mackenzie could act in consultative concert with a small group of like-minded, leading Liberals, hoping that the disparate group of men calling themselves Reformers or Liberals would follow.

Given the above characteristics, the Liberals performed remarkably well in the general election in the summer of 1872, gaining good representation in Quebec and a majority of the seats in the Maritimes and in Ontario. Mackenzie campaigned in nearly 20 Ontario constituencies other than his own, a clear measure of his growing personal authority and of the increasing extent to which he was seen as party leader at that point. Issues such as the Treaty of Washington of 1871, the terms of union for British Columbia and the expenditures associated with it, and the troubles with Louis Riel* in Manitoba told heavily against the Conservatives. Still, the Liberals did not form the government. Mackenzie had nevertheless demonstrated his ability, in the election and in his overlapping involvement at the provincial level. A member of the Ontario legislature since 1871 for Middlesex West, he served briefly as treasurer in the government of Edward Blake, from 20 Dec. 1871 to 15 Oct. 1872, in which year dual representation was ended in Ontario. His resignation from provincial politics was accepted in October, only a few days after he, Blake, and Brown, in a master stroke, had persuaded Oliver Mowat* to become Liberal leader in Ontario.

When, finally, the federal party formally elected Mackenzie its leader in March 1873, he was intensely pleased. He had suggested that others – Dorion, Holton, and particularly Blake – were more worthy, and claimed that he sought only the best interests of the party. His self-effacing efforts went for naught. He was chosen leader by a group of peers who, in vesting new authority in him, more firmly defined the party. Whips were appointed [see Sir James David Edgar] and a national political committee was planned, forms of organization that Mackenzie had at one time resisted as vehicles for Holton’s perceived ambitions.

Within a month of Mackenzie’s becoming leader, the Pacific Scandal had broken. The Liberals uncovered the massive flow of money from Montreal capitalist Sir Hugh Allan* to the Conservative party during the election of 1872 in presumed exchange for the Pacific railway charter [see Henry Starnes]. Mackenzie was scandalized by the rumours he heard as early as February 1873. Quebec Liberal Lucius Seth Huntington* laid public charges against the Conservatives on 2 April. After a strenuous rearguard action, Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald abruptly resigned on 5 November. Mackenzie and the Liberals thus had power dumped into their laps. The scandal precipitated and hardened Liberal suspicions about large concentrations of wealth and the influence of such wealth on government. A Liberal party with ideological leanings towards free trade and individual enterprise naturally pointed out that the scandal involved a rejection of the norms of competition and an assertion of monopoly power. The legislative expression of Liberal hostility towards monopoly and unfair competition was persistent after 1874. Mackenzie openly voiced that attitude, for example in relation to the Marine Electric Telegraphs Act of 1875, which regulated construction and maintenance. Liberals consistently associated their antagonism to protective tariffs with their fear of monopoly. Connected with their suspicions about monopoly was their fear of collusive, unparliamentary action on the part of the Conservative leaders.

Mackenzie was a fierce defender of the supremacy of parliament, as were his Liberal colleagues. The defeat of the government of John Sandfield Macdonald* in Ontario on 18 Dec. 1871 and the establishment of the Blake government, in which Mackenzie served, had revolved around the issue of parliamentary supremacy. Mackenzie’s motion, on which the Sandfield government was defeated, accused it of being a corrupt coalition government intent on making patronage expenditures unregulated by parliamentary votes: a “deliberately inaugurated . . . system . . . was destroying our Parliamentary system of Government.” The same issue was at the root of the Pacific Scandal. The powers that the Macdonald government had wanted in the charter of the Canada Pacific Railway Company in 1872 were attacked on the grounds that they pre-empted the right of parliament to decide on subsidies, routing, land grants, and conflict of interest. After the scandal broke, the intense struggle in parliament over the way in which it was to be investigated displayed the Liberals’ faith in a parliamentary, as opposed to a judicial, inquiry.

On 5 November Mackenzie was requested by Governor General Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*] to form his first administration, amid some doubt as to his suitability as a prime minister. The most pressing decision he made, other than the difficult judgements involved in forming a cabinet, was to call an immediate election. The election of January 1874 had the scandal as its key issue, and the demoralized Conservatives were routed. Mackenzie had a huge majority.

Yet even at this point, and throughout its tenure of power in the mid 1870s, the Liberal party fell short of ideals of cohesion. Problems arose in part out of tensions underlying Mackenzie’s leadership. Blake was widely regarded as a more natural leader for the party, though he had removed himself from consideration as its formal leader in early 1873. Yet Blake created a difficulty and for other reasons than his ability, personal problems, fluctuating ambitions, and occasionally overweening sense of self-importance. Although he and Mackenzie were united in their fundamental attitudes, Blake had a more radical reform agenda. This and his significant following, which encompassed the nationalist Canada First movement [see William Alexander Foster*], including its protectionist elements, generated a rift within the party. The pressures for him to be in the cabinet, even to be prime minister, were intense. Blake sat, reluctantly, as a minister without portfolio from the time Mackenzie’s first cabinet was formed, in November 1873, to February 1874, when he resigned. By the autumn of that year, however, because of disputes over the government’s treatment of British Columbia [see Andrew Charles Elliott*], Blake had the temerity to suggest that Mackenzie step aside for him as prime minister. The exchange that followed between the two men soured their relationship: trust was lost over their differences on the terms proposed by Colonial Secretary Lord Carnarvon for the British Columbia difficulty and over their profoundly dissimilar recollections of events surrounding Mackenzie’s appointment as prime minister in 1873. Blake believed that Mackenzie, after he had accepted Dufferin’s request to form a government, had asked him whether he wanted the job. Refusal, Blake felt, was the only honourable response. Mackenzie, however, claimed the conversation, including Blake’s refusal, had taken place before his acceptance. Moreover, when Mackenzie gave his explanation to Blake in September 1874, it led Blake, a master at the interpretation of nuance, to think that Mackenzie had been requested by Dufferin to ask him to consider becoming prime minister. Only on 15 October did Mackenzie explain that his talk with Blake had been undertaken on his own responsibility, over objections by Dufferin. It is not clear that Blake was satisfied by this account, as some significant misunderstanding had indeed taken place. In the interim, rebellion by a cave of Blake’s supporters and allies culminated in the public excitement caused by Blake’s enunciation of his radical program at Aurora, Ont., on 3 October. Though Blake may have been innocent of ill-will and though the speech may have held little that was new (Mackenzie believed both possibilities), from an outside perspective the statements set Blake up as an alternative leader to Mackenzie. It again became imperative to include him in the cabinet, something finally accomplished on 19 May 1875 by means of delicate negotiations through third parties. Blake served as minister of justice until 7 June 1877, when he resigned citing reasons of poor health, and then as president of the Privy Council, from 8 June to the beginning of 1878.

Blake was not the only highly competent Liberal whom it was difficult to lure into the cabinet. Luther Holton, the Montreal-based businessman-politician who Mackenzie thought would make a good finance minister, frequently refused to enter the cabinet. Mackenzie ascribed this reaction, at various times, to Holton’s feelings of personal inadequacy, to his perceived desire to have the prime minister’s job, to his purported plotting with Blake or Blake’s friends, or to the long-drawn-out death of a daughter. Ironically, when Holton expressed a desire for a cabinet position, there was no available place.

Mackenzie’s complaints about the inadequacies of his cabinet directly reflected the weaknesses of the Liberal party in his period of leadership. Few of the ministers, he thought, took on their fair share of parliamentary debate, but that partly reflected his own vigorous work habits. William Buckingham, his secretary, noted that he constantly took up the debating slack left by other ministers: he did not expect enough of them. Only five of his ministers held the same post throughout his administration: Mackenzie himself in public works, Albert James Smith* in fisheries, Richard John Cartwright* in finance, Isaac Burpee* in customs, and Thomas Coffin* as receiver general. Of this group only Cartwright was a powerful and regular speaker in the commons. Mackenzie felt the absence of good men in cabinet in another way. He made decisions on a consensual basis, explicitly so when he was de facto leader of the opposition between 1867 and 1873 and implicitly when he was prime minister. In letters to other leading Liberals he often sought advice about tactical and strategic political decisions: Holton, Alfred Gilpin Jones* of Halifax, Cartwright, Dorion, and especially George Brown were among those he consulted. This process, which Mackenzie saw as a natural outgrowth of the character of his party, did not reveal any personal weakness, even though at times he was accused of still being Brown’s second-in-command. Mackenzie rejected that notion and his correspondence with Brown gives it the lie. Brown was consulted on tactics because he had good, though consistently optimistic, judgement. Mackenzie used him and the Globe as political tools in turn, and Brown saw himself as no more than a stalwart and leading supporter.

To strengthen the party, adequate regional and ethnic representation in the cabinet was necessary, but that approach thinned the choices. Selection in Quebec was complicated by the need for a strong French Canadian lieutenant. Dorion, Mackenzie’s first minister of justice, was ideal for the position, but his long service in law and politics and his wish for a more predictable life led Mackenzie to appoint him to the chief justiceship of Quebec in 1874. Thereafter, French Canadian leadership in the party floundered. Télesphore Fournier did not have an adequate following, and was named to the newly formed Supreme Court of Canada in 1875. Luc Letellier* de Saint-Just was a senator and therefore inappropriate as a leader, and, in any case, Mackenzie named him lieutenant governor of Quebec in 1876. Félix Geoffrion, whom Mackenzie brought into the cabinet with the express desire to make him a Quebec lieutenant, became increasingly incapable of doing the work required by his Department of Inland Revenue. Joseph-Édouard Cauchon* had some leadership credentials, but he had a sullied reputation on first entering cabinet. He lost his usefulness altogether once he had helped resolve the Liberals’ difficulties with the Roman Catholic hierarchy in Quebec in 1876, following L. S. Huntington’s attack in Argenteuil on clerical intervention in politics. He then was shifted to the lieutenant governorship of Manitoba. By 1876 Mackenzie was desperate for a stronger figure, particularly one from the Montreal region. The sign of his desperation was the choice of Toussaint-Antoine-Rodolphe Laflamme, first as minister of inland revenue. An able lawyer, Laflamme had none the less been closely associated with the Institut Canadien, which the Catholic hierarchy viewed as free-thinking and anti-clerical. Only a young Wilfrid Laurier*, who had entered the commons in 1874, seemed to offer long-term relief, but he lacked experience for leadership and refused to enter cabinet until Cauchon left.

Good representation from the Maritimes was also difficult to obtain. Isaac Burpee, as Mackenzie saw it, was only willing to deal with matters directly pertaining to his Department of Customs. The minister of the interior, David Laird* from Prince Edward Island, was appointed by Mackenzie in 1876 to the lieutenant governorship of the North-West Territories because of his abilities. A. J. Smith, William Berrian Vail*, and Thomas Coffin were not the assets Mackenzie may have hoped they would be, and only by recruiting A. G. Jones in early 1878 as minister of militia and defence (he had previously taken a modest leadership role within the administration) was the representation from the region made more than acceptable.

Yet inherent in these troubles lay Mackenzie’s achievement in forging a national Liberal party. His initial cabinet and later alterations welded not only personalities but regional coalitions to the Liberal party. In the Maritimes Smith, Vail, Coffin, and Jones had opposed confederation. Coffin and Burpee drifted on the fringes of the Conservative party, waiting for patronage, until the Pacific Scandal pushed them over to Mackenzie. Coffin’s inclusion in cabinet was a price the prime minister was willing to pay for the support of a clique of Nova Scotian mps. Burpee was representative of urban and commercial New Brunswick; Jones later performed that function for Nova Scotia. However, in New Brunswick, Burpee was overshadowed by Smith, who sat in the commons as an independent political chieftain until 1873, when Mackenzie garnered him. Smith, despite growing fat and lazy in office (Mackenzie’s despairing opinion of him), delivered 12 of 16 New Brunswick seats to the Liberals in the election of 1874 and in the disastrous defeat of 1878 he still took 11. The process whereby Mackenzie established the Liberals as a national party in the Maritimes was symbolically completed by his speaking tour there with R. J. Cartwright during the 1878 campaign.

In Quebec a similar process of consolidation and growth took place. Through Cauchon and, more prominently, Laurier, Mackenzie began to defuse the hostility of the French Canadian Catholic hierarchy towards Liberals. He had already undertaken considerable efforts to draw Irish Catholics into the party. In Laurier he had recruited the key man of the next generation of Liberal leaders.

Mackenzie and his cabinets nevertheless faced significant limitations in the policies they could fashion and the problems they could solve. The general election of 1874 gave the Liberals a majority in Quebec and Ontario; indeed, they had an overwhelming preponderance in parliament. Cartwright pointed out to his fellow ministers in 1875 that “no stable govt. is possible except in one of two ways, i.e. either by securing a decisive majority in Ontario and Quebec taken together, or by deliberately purchasing the smaller provinces from time to time.” Mackenzie agreed, at least in part. Rooted in Ontario, the Liberals faced possible tension in maintaining their position in Quebec and control over their Maritime representatives. The Maritimers could be bought off by patronage and log-rolling, but there was never enough of that. At times they could cause a decisive shift in party policy by acting in concert, as they did in 1876 when they forced the government to abandon its plan to adjust the tariff upwards.

Quebec was an even more difficult problem. The Liberal hold on the province was tested by several developments, the first of which concerned amnesty for Louis Riel. Sir John A. Macdonald, acting through Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché, had promised him amnesty for his activities at Red River in 1870. There was a general expectation in Quebec that the Liberal government would fulfil this promise, though it had been given before the death of Ontario Orangeman Thomas Scott* at the hands of Riel’s provisional government. Riel’s election to the House of Commons for Provencher in January 1874 and the arrest, conviction, and sentencing of Ambroise-Dydime Lépine*, Riel’s lieutenant, on the Scott matter, made amnesty a lively issue. Mackenzie naturally prevaricated – although amnesty might soothe Quebec, it would provoke Ontario. But the Lépine complication actually brought a resolution to the difficulty, for his sentence of death was commuted by the governor general, Lord Dufferin. Here the Liberals hid behind imperial skirts. In February 1875 Mackenzie’s government granted amnesty to all of those associated with the Manitoba problems, including a provisional pardon to Riel. Yet the issue made the Liberals extremely aware of their weaknesses in Quebec.

On the tail of the Riel question came another problem, even more crucial. As a result of the growth of ultramontanism in Quebec in the late 1860s and early 1870s [see Ignace Bourget*; Louis-François Laflèche], clerical hostility towards both Rouges/Liberals there and Liberals in Ontario was commonplace. Ultramontanism, moreover, appeared to threaten the position of anglophone Protestants within Quebec. On 30 Dec. 1875 at a by-election in Argenteuil L. S. Huntington spoke his feelings on the relation of clerics and politics. Clerical intervention in elections was a wrong associated with the Tories, he declared. He called upon the Protestants of Quebec to align themselves with the Liberals in defensive reaction against ultramontanism. The repercussion among leading French Canadian Catholics was sharp. They feared that Huntington spoke for the Liberal government as a whole. Mackenzie chose the better part of valour and claimed that Huntington had expressed purely personal opinions, not those of the government or of the Liberal party. Yet, in private, he wrote to George Brown that what Huntington had said was absolutely true, though impolitic. In early 1876 the Liberals traced their defeat in three Quebec by-elections, including one in Charlevoix [see Pierre-Alexis Tremblay*], to the Huntington affair. The party was being demoralized in the province. The Liberals counter-attacked on several fronts. First they undertook court challenges of clerical involvement in elections [see Édouard-Charles Fabre; Sir William Johnston Ritchie]. These challenges did not profoundly alter clerical attitudes, so, through Cauchon, Mackenzie appealed to Rome for a papal legate (George Conroy*) to investigate Canadian conditions. Laurier, intent on proving himself, worked hard to temper clerical involvement in electoral politics and clerical hostility to Liberals.

In economic terms, the dominant characteristics of the time the Liberals were in power were recession and depression. The downward trend of the economy had been signalled by the American crash of September 1873; by mid 1874 the effects of recession in Canada could not be mistaken. Conditions remained poor from then until late 1878, though the situation varied from sector to sector and from region to region. The agricultural sector in Ontario, which Mackenzie mistakenly believed would give his party hearty support in the general election of 1878, did relatively well, whereas towns and cities in which there had been substantial industrial expansion prior to 1874 suffered and showed electoral hostility to the Liberals. These negative economic conditions not only cost them seats in by-elections but enhanced key elements of their outlook on economic policy. The conditions made them tightfisted: this was certainly the case with railway policy.

A desire for fiscal restraint that derived from a concept of minimalist government had made Liberals, including Mackenzie, suspicious of the union and railway deal struck by the Macdonald government with British Columbia. When the deal was made public in 1871, the Liberals had recoiled in horror. To have promised to build, at enormous cost within ten years, a railway that would serve only a tiny population was an act bordering on fiscal insanity, Mackenzie would indicate in 1874. He did, of course, want westward expansion and railway construction. However, he and other Liberals objected to the poor planning of the railway and to the high cost associated with quick construction. Taxes should not be increased to pay for the railway: this assurance in the charter of the Canada Pacific Railway Company in 1872 was crucial from the viewpoint of the Liberals. Mackenzie returned repeatedly to this point in the tense discussions with British Columbia that followed.

Upon becoming prime minister he inherited a difficult situation. The railway had to go forward and consequently it had to be adequately financed. The Conservatives had not begun construction and the government of British Columbia had already issued complaints. Given fiscal restraints and a Liberal emphasis on avoiding tax increases, Mackenzie would have liked to see private financing. The Canadian Pacific Railway Act, passed in the spring of 1874, made such financing an available option. Preliminary discussions were actually held with George Stephen*, who, however, told L. S. Huntington in December that he did not want to risk his own money. That response was not surprising in existing economic conditions. The depression, for example, involved some resounding American railway collapses. The Liberals had to go with direct government financing out of necessity. Mackenzie expressed goodwill towards British Columbia, and indicated positive intentions, but he made it clear that the existing timetable for construction was impossibly short. Indeed, the pressure in Liberal ranks against quick construction was enormous. Blake was intensely opposed to extending a service at exorbitant cost to a tiny British Columbian population.

A circumspect policy of planning and surveying, and preliminary work on roads, waterways, and telegraph lines, with rail construction not too far in advance of the vanguard of settlement, was an obvious result. Mackenzie naturally wanted to utilize existing American lines south of the Great Lakes, rather than build through the uninhabited territory north of Lake Superior. The demands for lines in Manitoba and the need to provide patronage and log-rolling in the Port Arthur (Thunder Bay) region and in Manitoba could be met through contracts for preliminary railway work and for ancillary roads and telegraph lines. Mackenzie’s strategy, notably the use of an American bypass, was similar to that of Macdonald prior to Riel’s provisional government in Manitoba, and the plan appealed to interested capitalists.

In these circumstances Mackenzie called for a rescheduling of construction with British Columbia’s consent. In February 1874 he commissioned party stalwart J. D. Edgar as the government’s envoy to reach a readjustment with the government of British Columbia. Its premier, George Anthony Walkem*, did not find the proposed readjustment acceptable; with specious reasoning he rejected Edgar as envoy in May and sent a sharp protest to Britain.

In this fashion the main provincial-federal struggle of Mackenzie’s stay in power entered the realm of imperial relations. Colonial Secretary Lord Carnarvon suggested himself as arbitrator between the two levels of Canadian government. Despite Mackenzie’s aversion to this apparent interference in internal Canadian affairs, Carnarvon proceeded, delivering in August terms for a basis of agreement that were less than those desired by British Columbia but much more than the Mackenzie government was willing to contemplate.

The Mackenzie government grudgingly accepted the Carnarvon Terms, but fiscal responsibility and constitutional problems prevented their full implementation. The Senate, dominated by Conservatives, refused to pass a commons-approved bill to finance one key element in the terms, building the Esquimalt–Nanaimo line in British Columbia. Carnarvon then refused to permit the enlargement of the Senate requested by Mackenzie. Disputes over what the government should do raged for months, as Governor General Lord Dufferin, the imperial government, and British Columbia tried to force further commitments from the Mackenzie administration. Only after recriminations so raw and furious that the diplomatic Dufferin felt a passing urge to hit his prime minister, was a compromise reached in 1876, by which Mackenzie agreed to start construction in British Columbia two years later.

This lengthy struggle over the Carnarvon Terms, and the caution generated by the Liberals’ economic outlook and by depression conditions, has overshadowed what was actually an energetic program of railway undertakings. Total Canadian mileage increased from 4,331 in 1874 to 6,858 in 1879. This expansion was largely the result of the completion of the government-financed Intercolonial Railway, under engineer Sandford Fleming*, and the construction of track under government contract in Manitoba and between that province and Lake Superior [see Hugh Ryan]. The crucial process of surveying in the west was pushed ahead unremittingly. Some 46,000 miles of potential line were blazed between 1871 and 1877 and about 12,000 miles were actually surveyed. Construction of telegraph lines from Port Arthur to Edmonton was undertaken. In essence, the Carnarvon Terms, with the thorny exception of the Esquimalt–Nanaimo line [see Robert Dunsmuir*], were met. These were impressive accomplishments under difficult circumstances.

Other economic policies pursued by the Mackenzie administration were also constrained by circumstances. In the case of reciprocity, the Mackenzie government felt that the previous administration had not sufficiently pursued improved trade relations with the United States. The Liberals intended to piggyback the trade issue on the outstanding issue of American payment for access to Canada’s and Newfoundland’s inshore fisheries, as specified in the Treaty of Washington [see Sir John A. Macdonald; Peter Mitchell]. The Canadian hand would be strengthened further by having the chief negotiator appointed as the representative of Canada. George Brown got the job in January 1874. The eternal optimist, Brown negotiated hard with the American secretary of state, Hamilton Fish, but by the time a reciprocity treaty was agreed upon in June, the American Senate was close to adjournment and the agreement, much more extensive than that of 1854, slid into limbo.

American political and economic conditions probably made it impossible to implement. However, the furore over the proposal in Canada served to highlight the key beliefs, strengths, and weaknesses of the Liberals. Mackenzie sought to ensure support for his party among farmers in Ontario, export-oriented merchants, fishermen, and shipping interests in the Maritimes. The agreement’s inclusion of a large list of manufactures and the reduction of customs duties indicated that the Liberals were genuine free-traders. In terms of its contents and the methods by which it was reached, the agreement signalled the Liberals’ wish to see Canada become more commercially independent from Britain. At the same time, the trade proposals generated a more unified protectionist outlook among Canadian manufacturers and to a lesser degree in the general business community, an outlook already partially precipitated by the depression.

The economic liberalism of the Mackenzie government was also made explicit in the tariffs of 1874, 1876, and 1877. Mackenzie, at pragmatic extremes, expressed a willingness in 1874 to keep protection in place and to increase it when the government needed revenue, but he made his distaste for these procedures obvious. None the less, tariff increases were made necessary by growing deficits rooted in the government’s fiscal inheritance and in falling tariff revenues. Protectionists, recognizing the government’s needs, mounted campaigns to gain their own ends. From their perspective, the 1874 tariff introduced by finance minister R. J. Cartwright was insufficient: designed to increase revenue, it virtually avoided all overt signs of protectionism.

Liberal free-trade proclivities were more severely tested in 1876, when inadequate revenue levels necessitated further tariff revisions. The government faced much protectionist agitation, which was expedited by a parliamentary committee on the causes of the current depression. The free-trade focus of the government wavered: Mackenzie heard Liberals argue for a tariff increase of as much as 5 per cent. Higher tariffs were indeed planned, but sectionalism within the party prevented them. Leading Maritime Liberals threatened open opposition to any tariff increases and this threat strengthened Mackenzie in his convictions. The 1876 tariff changes were minor. Protectionists then sought to influence the government on the basis of its apparent vulnerability to pressure from the Maritimes. Unified Nova Scotian coal interests demanded tariff protection, and protectionists used this demand as the Trojan Horse to attempt to gain generally higher tariffs. The 1877 tariff was, however, aimed only at garnering more revenue. The events of 1876 and 1877 formed a temporal dividing line, which separated protectionists from the Liberal party for almost the rest of the century.

Part of the Liberals’ defence of free trade was that Canada’s economic relationship with the mother country should not be broken by unnatural commercial restrictions. Mackenzie’s sense of loyalty to the British empire was strong, both before and during his period in power. Thus he accepted the notion of a transcontinental Canadian railway as a link of empire; thus his loyalty to British constitutional practices. At the same time, however, he was eager to achieve greater powers of self-direction for Canada. Though he was cautious about an independent Canadian treaty-making power in the immediate aftermath of confederation, when advocates of such power (among them Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt, L. S. Huntington, and A. J. Smith) supported a parting of the ways with Britain, by 1882 he could support the idea.

The Treaty of Washington of 1871 had been decisive in Mackenzie’s thinking on this issue. He felt that the Conservative leader, Macdonald, performed poorly for Canada as a British commissioner, and that the British negotiating team was so intent on smoothing relations with the United States that it ignored Canadian interests. Mackenzie saw the appointment of George Brown as Canadian plenipotentiary, for the negotiations on reciprocity with the United States in 1874, as a necessary step in achieving optimal results. His successful effort in having a Canadian, A. T. Galt, appointed as the British commissioner in arbitrage in 1875–77 over the fisheries dispute with the United States was similarly motivated [see Sir Albert James Smith].

Analogous approaches were apparent in non-commercial concerns. From a Liberal perspective, the Supreme Court of Canada was established in 1875 to create more effective Canadian decision making. Macdonald’s government had initiated moves towards such a court, but it was the Liberal minister of justice, Télesphore Fournier, who actually introduced the Supreme Court Bill. Nationalist-minded Liberals amended it, with Mackenzie’s strong support, to limit sharply appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Britain. Disappointingly, the amendment became inoperative.

Mackenzie, and Blake to an even greater degree, had concerns about the activities of Lord Dufferin in relation to Canadian independence of action and parliamentary democracy. The suspicion was founded on the governor general’s excessive support of Macdonald in the Pacific Scandal, which, Mackenzie felt, constituted a degree of British interference in Canadian domestic affairs. It was also apparent in the tension over the Carnarvon Terms and was manifest in Blake’s hostility towards Dufferin for his undirected decision in 1875 to commute Lépine’s sentence in the amnesty affair.

The blend of attachment to empire and stalwart Canadian nationalism that Mackenzie espoused was eminently clear in his approach to matters of defence. He himself had been a major of militia at Sarnia during the Fenian troubles prior to confederation [see Michael Murphy*; John O’Neill*], a decisive event in the formation of a sense of nationality among the thousands of Canadians who served. When Conservative cabinet minister and sometime Reformer William McDougall* virtually accused Mackenzie of disloyalty to the crown during the 1867 election campaign, Mackenzie repudiated the charge by pointing to his militia service. He asserted in 1868 that the defence of Canada was not merely a matter of domestic concern but had to be fashioned in full cooperation with the British. However, the weakness he saw in the Canadian militia was leadership, which simply could not be provided by a thin array of British officers. Thus, as prime minister, he fully endorsed both the reorganization of the Department of Militia and Defence, of which W. B. Vail was minister, and the establishment of a military training college in Canada in 1874 [see Edward Osborne Hewett].

At the same time that Mackenzie’s Liberals sought greater national powers vis-à-vis Great Britain, they reflexively stood as protectors of provincial rights in Canada. The strong sectional view that Reformers had displayed under Brown readily translated into a provincial-rights stance for the Liberals after confederation [see Sir Oliver Mowat]. In the case of the tensions over Catholic rights in education in New Brunswick [see Timothy Warren Anglin] Mackenzie’s perspective was clear, if self-serving. It was, of course, politically convenient for him to claim that the issue lay entirely in the hands of New Brunswick. Mackenzie espoused provincial rights in a way that might also be interpreted as self-serving in the case of Luc Letellier de Saint-Just, lieutenant governor of Quebec in 1876. Saint-Just dismissed the provincial Conservative government of Charles-Eugène Boucher* de Boucherville in 1878 on the grounds that it had not given the office of lieutenant governor its constitutional due, by issuing edicts and signing documents under his name without consultation. His actions were constitutional, but they transcended the commonly accepted notions of the lieutenant governor’s powers, and so brought on the wrath of the federal Conservative party and demands for an inquiry and his dismissal. Mackenzie properly claimed that the electorate of the province was fully able to judge the case and that it was a matter of provincial concern. Even before they achieved power, the Liberals under Mackenzie had protested the giving of better terms of union to Nova Scotia on the assumption that this grant infringed on the financial arrangements other provinces had obtained at confederation. When Macdonald gave larger representation to British Columbia and Manitoba in the House of Commons than their populations warranted, the Liberals protested on the grounds that such action violated provincial rights and the sacred principle of representation by population. Mackenzie’s respect for provincial rights did not mean that he gave way to the provinces on contentious issues. But he did avoid adversarial approaches. Rather than taking the issue of Ontario’s boundary with Manitoba and the North-West Territories to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, as Macdonald had planned to do, he chose in 1875 to settle the matter by arbitration. Indeed, it was more by a process of negotiation between the federal and provincial governments that the matter was resolved in 1878, though Macdonald refused to honour the award.

Mackenzie’s government established an enviable record of reform legislation, especially in its first two years of power. The most prominent of these laws was that on electoral reform, passed in 1874. Liberalism stimulated Mackenzie and his party to try to create a political context in which the popular will (as defined by those who had the right to vote) could find proper expression. This modestly democratic concept underlay not only the Liberals’ ideas on Canada’s relationship to Britain but also their position on electoral reform. Throughout the 1850s and 1860s Mackenzie had believed consistently that one reason the Liberals had difficulty gaining power was the electoral trickery of their opponents, who bribed, treated, and impersonated their way to victory. The electoral sins of the Conservatives in 1872 seemed to confirm this interpretation of their conduct. In 1873 the Liberals managed to force from the Macdonald government, in a weakened state after the election of 1872, feeble acts on electoral reform. In the aftermath of the Liberal victory of 1874 the Dominion Elections Act was passed. It included the secret ballot, the legal requirement to hold the election in all ridings on the same day to prevent engineered bandwagon effects, and the removal of property qualifications for candidates for the commons. To enforce this new law more effectively, justice minister Antoine-Aimé Dorion brought in a bill that placed the trial of controverted elections within the judicial system rather than within the scope of a parliamentary committee. In these laws, strong egalitarian notions were apparent.

The temper of the legislation passed during Mackenzie’s régime was the temper of his Liberalism. Much of that legislation involved organizational and regulatory rationalization. The Post Office Act of 1875, which amended and consolidated the laws for regulating the postal system, introduced a number of important changes, including the compulsory prepayment of postage and a reduction of rates on certain classes of mail. This act was associated with the postal convention that year with the United States to expedite the passage of mail in North America. At the same time door-to-door delivery of mail, which had been established in Montreal in 1867, was extended to all major Canadian cities. The North-West Territories Act of 1875 not only brought together existing laws relating to the territories but provided the region with a practical constitution. (Mackenzie, who was responsible for the rough drafting of the bill, tacked on as an afterthought, in the section on taxation, provisions permitting separate Roman Catholic schools on the Ontario model. Only a sharp Senate debate on those provisions gave a foretaste of the controversy they would produce in later decades [see D’Alton McCarthy].) The Public Accounts Audit Act of 1878 affirmed and to a degree rationalized existing practice concerning lines of responsibility for governmental fiscal management [see John Lorn McDougall*]. As well, the tariff changes of 1877 were accompanied by a wholesale revision of the regulatory structure of customs administration. The Collection of Criminal Statistics Act of 1876 and the Weights and Measures Act of 1877, both of which bore the mark of Edward Blake’s precise mind, followed the same trend towards regulatory efficiency.

These and other laws were a signal contribution on the part of Mackenzie’s government. Some of the legislation, for example the Weights and Measures Act, provided a regulatory context which tried to ensure fairer competition and protection for the consumer. The Inspection of Staple Articles Act of 1874, the Inspection of Petroleum Act of 1877, the Insolvent Act of 1875, the Customs Act of 1877, the Canada Joint Stock Companies’ Act of 1877, and the insurance acts of 1875 and 1877 all reflected a drive to establish a more effective legal context for the free operation of market forces. The insurance acts, for instance, required federal licensing of insurance companies, deposits to cover a level of liability, and the publication of key financial data. The office of superintendent of insurance, established to deal with life insurance companies and first held by John Bradford Cherriman*, had considerable powers of inspection. The Penitentiary Act of 1875 was intended to reform the running of penitentiaries through greater fiscal control and a more effective, better-controlled inspectorate.

Such legislation, which exhibits the ample scope of Liberal reformism under Mackenzie, was not as controversial as the Canada Temperance Act of 1878. Mackenzie personally disapproved of any use of alcohol as not only dysfunctional but immoral. Tipsiness or drunkenness in the commons appalled him. Yet he viewed temperance legislation with suspicion, largely because of the political divisiveness of enforced abstinence. He was, however, able to countenance the temperance act (also called the Scott Act after Secretary of State Richard William Scott*) because it instituted a form of local option. Yet even that move was a political error: it alienated voters of all points of view and caused the liquor interest to campaign against the Liberals in the election of 1878.

Scandals also worked against Mackenzie that year. Although he was, within the boundaries of late-19th-century political life, a man of probity, he recognized the necessity and usefulness of patronage from the earliest stages of his political involvement. As prime minister he expected competence as well as service to the party from the beneficiaries of patronage. He had no intention of sweeping out Conservative appointments merely to benefit the Liberals. Besides, Lord Dufferin held very strongly to the principle of a permanent civil service. Still, the prime minister enjoyed rewarding his friends, and himself, within the scope of legitimate political practice. Sometimes the practice went beyond the pale of the acceptable: when he was treasurer of Ontario in 1871–72, he had a number of public buildings insured by the Isolated Risk Fire Insurance Company of Canada, which he had helped found in June 1871 and of which he was president. Mackenzie’s brothers in particular were capable of administering soot to his reputation. In late 1874, falsely believing that the price of steel rails had fallen to an all-time low, he authorized the purchase of 50,000 tons of rails through a firm in which his brother Charles had a large interest. Alexander thought he had effected a saving for the dominion. He had not. When the matter came to light in 1875, he was accused not merely of nepotism but of nepotism at the expense of the country. He denied both: the bid accepted had been the lowest.

His efforts to create institutional probity in the Department of Public Works, the ministry he had compulsively undertaken when he became prime minister, had limited success. In that department his interests in construction, in fiscal retrenchment, and in rooting out what he conceived to be political corruption, fused. Though corruption continued in this large department, no real blame could be laid at Mackenzie’s door except perhaps in terms of administrative practice. He swore to accept the lowest bids on public works contracts. Bids, however, were not required to be submitted on the same day and were opened as they came in, thus creating opportunities for contractors, through bribery, to cheat. He was more directly involved in the Neebing Hotel scandal of 1877, which developed from the government’s selection of the Fort William town plot (Thunder Bay) as a terminus of the Pacific railway [see Thomas Marks; Adam Oliver*]. A Liberal contractor had been selling land to the government at inflated prices. The contractor’s partner was the evaluator who approved the prices. Mackenzie claimed ignorance, though he had appointed the evaluator.

The 1878 session of parliament, and the Liberals’ mandate, ended on 10 May. Mackenzie called the federal election for 17 September. His own instinct had been to call it for the spring, when momentum could still be harnessed from the provincial victory in May of the Liberal party in Quebec under Henri-Gustave Joly*. Some Liberals, however, recoiled from a spring election because their political machinery was not in place. The uneven preparation of the party was to some degree a product of Mackenzie’s heavy work-load as prime minister and minister of public works. Taking on that department had been the egregious personal error of his political career. His ferreting instincts were too fully aroused by the finances of the department, so the burden of detailed work he faced as minister was enormous; furthermore, he did not effectively use the department to garner better financing and support for the party.

Mackenzie’s strength as a party organizer, which had stood him in good stead in his early political career, was thus underutilized during his administration. By the mid 1870s a number of leading Ontario Liberals felt distinctly uneasy about the state of the party’s machinery, even though Mackenzie had made efforts to give the parliamentary party some structure after he had gained full leadership. J. D. Edgar and others struggled to establish the Ontario Reform Association in 1876, with George Robson Pattullo as its full-time secretary and organizer, but without adequate support from Mackenzie. A national organization was not forthcoming. After the 1878 election Mackenzie would strongly support the formation of a central Liberal club fashioned after the United Empire Club of the Conservatives, thus indicating his concern about Liberal organization. Such a club, however, was not established until 1885 in Toronto.

Mackenzie not only moved sluggishly on organization, he had also misjudged the direction of public opinion. As he noted to William Buckingham with some puzzlement in September 1878, just before the election, “My meetings have all been very successful, could hardly be more so, yet I find the Tories are everywhere confident, why I cannot understand.” He did not grasp the degree to which the voting populace had been swayed by protection or, to lesser extent, by issues such as the Letellier affair, the Scott Act, the sectionally divisive program for railway construction, and the scandals that had marred his own reputation. Though he accepted the notion that the protectionist issue would mean a substantial loss in urban support, he did not apprehend the extent to which the issue appealed to rural feelings. Nor did Mackenzie sense how far the Liberals had fallen in public estimation, although the reception given to some of Richard Cartwright’s unfortunate turns of phrase could have warned him. Fully committed to the tenets of economic liberalism, Cartwright declared in the commons in 1877 that governments could influence the business cycle no more than “any other set of flies on a wheel.” The Conservatives thereafter derided Liberals as just such a set of incapable and uncaring flies. Mackenzie did little to improve this increasingly negative image of the party. Minor riots over work and food in Montreal in 1877 – symptoms of the intensity of the depression – led the municipal government to plead for the release of funds promised for public works in the city. Mackenzie refused, citing budgetary constraints. Even his humble beginnings were turned against him. Years after his death, Goldwin Smith* could not resist repeating a barb often tossed, in various forms, at the prime minister for his obsession with detail, his unpolished manners, and his inflexibility: “a malicious critic might have said that if his strong point was having been a stone-mason, his weak point was being a stone-mason still.” It was a cruel but telling caricature.

As a result of the election in 1878 the number of seats held by the two parties virtually reversed from that in 1874. Mackenzie himself was only narrowly returned in Lambton. After the election there was a muted debate within the party leadership as to whether the government should wait until it was defeated in the house to resign or whether resignation should take place earlier. The latter opinion won out. The prime minister indulged in a paltry list of last-minute appointments, and then gave Lord Dufferin his letter of resignation from office, effective 9 Oct. 1878.

Mackenzie had more than once complained of the enormous burden of office, and how pleasurable it would be to lay it down. Yet the loss of office pained him deeply. Some contemporaries thought he retreated into himself; certainly his leadership of the party was lacking: no caucuses were called until late in the 1880 session, and then, reputedly, by the chairman of caucus, Joseph Rymal, to consider the question of leadership. By early 1880 the leadership aspirations of Edward Blake, who had been defeated in 1878 but was returned the following year, were clear, and discontent among Liberal mps began to crystallize. Mackenzie was aware of these trends, and either willingly or under direct pressure he announced his resignation as leader to the commons in the early hours of 29 April. Blake replaced him.

The scope of Mackenzie’s political life narrowed significantly after 1880. The deaths that year of the men he had felt closest to in political life, Luther Holton and George Brown, distressed him deeply and enhanced his feelings of political isolation. His declining health during the 1880s reduced his activities. His voice began failing him in 1882 and in his last years of parliament he rarely spoke. He nevertheless remained a strong party man and retained a compelling interest in politics. Having moved to Toronto after his party’s defeat in 1878, he was elected in 1882 in York East, which seat he would hold until his death.

Mackenzie’s business activities had begun to shift focus as early as 1871, when he had given up contracting. His fire insurance company, which he formed that year and which he attempted to foster nationally, prospered and that success perhaps encouraged him to expand into life insurance. In 1881 he became the first president of the North American Life Assurance Company (it had been chartered in 1879); virtually all of its founding members were Liberal luminaries, among them Sir R. J. Cartwright, John Norquay*, and Oliver Mowat. Almost from the first, the firm was national in scope, having agents in all provinces by 1882. And it was successful, with Mackenzie as its president until 1892, though for the last few years he was inactive.

Mackenzie also took to writing: in 1882 his Life and speeches of Hon. George Brown was published in Toronto. He wanted to erect a literary monument to Brown; at the same time he clearly wanted to reassert the Reform tradition. His previous writing had been adversative: his early journalism and the speeches honed for publication in the 1870s. So too was the sarcasm and invective in some of his private letters, where, for example, Samuel Leonard Tilley was dismissed as a “man not above mediocrity” and Sir John A. Macdonald appeared as a “drunken debaucher.” But this style of writing was ill suited to dealing with a close friend. It may have been also the sharp separation which Mackenzie made between his private and public life, and which he naturally extended to Brown in the biography, that rendered his depiction of the vibrant and intense editor of the Globe so wooden.

Throughout the gruelling public life that Mackenzie had fashioned, he drew sustenance from close family relations. The intensity and the hours of his work as prime minister and minister of public works had physically damaged him, he noted in letters to his brothers, to whom he remained close. His daughter, Mary, was also a correspondent and a confidante, though he avoided with her the sober political discussion to which he subjected his brothers. If not consistently, at least at various times during his administration, he lost a great deal of weight, a serious matter about which he could none the less joke light-heartedly with his second wife, Jane. She was his chief companion after their marriage in 1853. He had met her through his steady attendance at a Baptist church in the country near Port Sarnia, and Mackenzie took pleasure in sharing her piety. Reserved by nature, she had not functioned effectively as a political wife, unused, as a hard-working woman of rural origin might well be, to the requirements of fashionable entertaining at the apex of Canadian political society. The Liberal prime minister shielded her from those burdens as much as possible. His letters to Jane display an open affection and a gentle, broad humour, which was rarely discernible in the man at other times. They enjoyed several trips to Europe together after Mackenzie relinquished the Liberal leadership, one of which was financed by leading party members.

Alexander Mackenzie died on 17 April 1892, after being bedridden as a consequence of a fall near his home in early February. He did not have a state funeral. But attendances at services in Toronto and Sarnia were very large, and much public respect was paid the man.

[The chief manuscript sources for this biography, all at the NA, are the papers of Mackenzie (MG 26, B), George Brown (MG 24, B40), and Lord Dufferin (MG 27, I, B3). Other collections of value are the Buckingham papers at the NA (MG 24, A60) and those of Edward Blake (MU 136–273) and R. J. Cartwright (MU 500–15) at the AO. Also useful are the Mackenzie letters at the PANS (MG 100, 183, nos.6–8). The manuscript sources, however, are of a lower order of magnitude than those available for Sir John A. Macdonald. Printed contemporary sources therefore take on considerable importance. The House of Commons Debates are vital to understanding Mackenzie and his party and political milieu. For his early career the Sarnia Observer, and Lambton Advertiser (Sarnia, [Ont.]) is very useful, as is the Sarnia Lambton Shield, where some of Mackenzie’s most pungent writing appears. The Ottawa Daily Citizen and the Ottawa Times provide a good basis for gaining insight into the party context. The Toronto Globe is essential in developing an understanding of Mackenzie’s Liberal party.

A number of Mackenzie’s speeches were published, including Speeches of the Hon. Alexander Mackenzie during his recent visit to Scotland, with his principal speeches in Canada since the session of 1875; accompanied by portrait and sketch of his life and public services (Toronto, 1876); Address to the Toronto workingmen on the “National Policy” (Toronto, 1878); and Alexander Mackenzie et al., Reform government in the dominion; the pic-nic speeches delivered in the province of Ontario during the summer of 1877 (Toronto, 1878).

Two major biographies of Mackenzie have been published: William Buckingham and George W. Ross*, The Hon. Alexander Mackenzie; his life and times (Toronto, 1892), and Dale C. Thomson, Alexander Mackenzie, Clear Grit (Toronto, 1960). Buckingham and Ross’s effort is accurate and sympathetic, though not entirely uncritical of Mackenzie’s personality and tactics. Thomson’s remarkably comprehensive narrative is adept at portraying Mackenzie’s struggle with complex issues of cabinet, nationality, and reform, and does so without imposing a strict interpretive framework.

A succinct introduction to a part of the debate over the nature and origins of Canadian Liberalism is provided by R. Craig Brown’s introduction for Upper Canadian politics in the 1850’s, ed. Ramsay Cook et al. (Toronto, 1967), vii–xi. J. M. S. Careless, in his subtle and balanced biography Brown of “The Globe” (2v., Toronto, 1959–63; repr. 1972) showed the importance of metropolitan influence over central Canadian Reform, and found its origins in British, mid-Victorian liberalism, a point of view implicitly accepted by Thomson. They largely reject Frank H. Underhill*’s frontier and populist interpretation. It is instructive to read Underhill’s partial exploration of the “Political ideas of the Upper Canadian Reformers, 1867–78,” CHA Report, 1942: 104–15, which is loath to give credit to Mackenzie. Robert L. Kelley, in The transatlantic persuasion; the liberal-democratic mind in the age of Gladstone (New York, 1969), placed Mackenzie and Brown within a liberal ideology common to Britain, Canada, and the United States. This inflates the idea of mid-and late-nineteenth-century liberalism close to bursting. The notion of a dominant, consensual liberal ideology in central Canada is, of course, a separate issue.

The institutional development of the Liberal party from confederation to 1878, and Mackenzie’s role in that development, has generally been ignored. The historiographical agenda was given definition through Underhill’s fascination with the intellectual history of political issues and party typologies, as is apparent in his collection of essays entitled In search of Canadian liberalism (Toronto, 1960). William R. Graham avoided comment about the structure and organization of the Liberal party but examined issues and beliefs in “The Alexander Mackenzie administration, 1873–78: a study of Liberal tenets and tactics” (ma thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1944). Some useful material is also found in E. V. Jackson, “The organization of the Canadian Liberal party, 1867–1896, with particular reference to Ontario” (ma thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1962).

Mackenzie’s difficulties in structuring his cabinet are assessed in T. A. Burke, “Mackenzie and his cabinet, 1873–1878,” CHR, 41 (1960): 128–48. The recruitment of free-floating, former Conservatives into the Liberal party is discussed by Donald Swainson in “Richard Cartwright joins the Liberal party,” Queen’s Quarterly (Kingston, Ont.), 75 (1968): 124–34. Much of the published material on Mackenzie, Edward Blake, and the party deals with the contentious relationship between the two leaders. One might also examine G. E. Briggs, “Edward Blake – Alexander Mackenzie: rivals for power?” (ma thesis, McMaster Univ., Hamilton, Ont., 1965).

The chief political issues during Mackenzie’s régime have received thorough treatment. Peter B. Waite established a context of wonderful literary texture in Canada, 1874–96. W. H. Heick, “Mackenzie and Macdonald: federal politics and politicians in Canada, 1873–1878” (phd thesis, Duke Univ., Durham, N.C., 1966), provides a useful survey of the political struggle. The tariff debate has been assessed in my study A conjunction of interests: business, politics, and tariffs, 1825–1879 (Toronto, 1986). Appraisals of the railway dispute with British Columbia are available in two works by Margaret A. Ormsby, British Columbia and “Prime Minister Mackenzie, the Liberal party, and the bargain with British Columbia,” CHR, 26 (1945): 148–73; in Pierre Berton, The national dream: the great railway, 1871–1881 (Toronto and Montreal, 1970); and in G. F. Henderson, “Alexander Mackenzie and the Canadian Pacific Railway, 1871–1878” (ma thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, 1964). Berton’s jaundiced view of Mackenzie uncritically accepts the evidence of politically hostile witnesses in Can., Report of the Canadian Pacific Railway royal commission (3v., Ottawa, 1882). Mackenzie’s virtue survives, though tarnished. b.f.]

Cite This Article

Ben Forster, “MACKENZIE, ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 31, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mackenzie_alexander_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mackenzie_alexander_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ben Forster |

| Title of Article: | MACKENZIE, ALEXANDER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | January 31, 2026 |