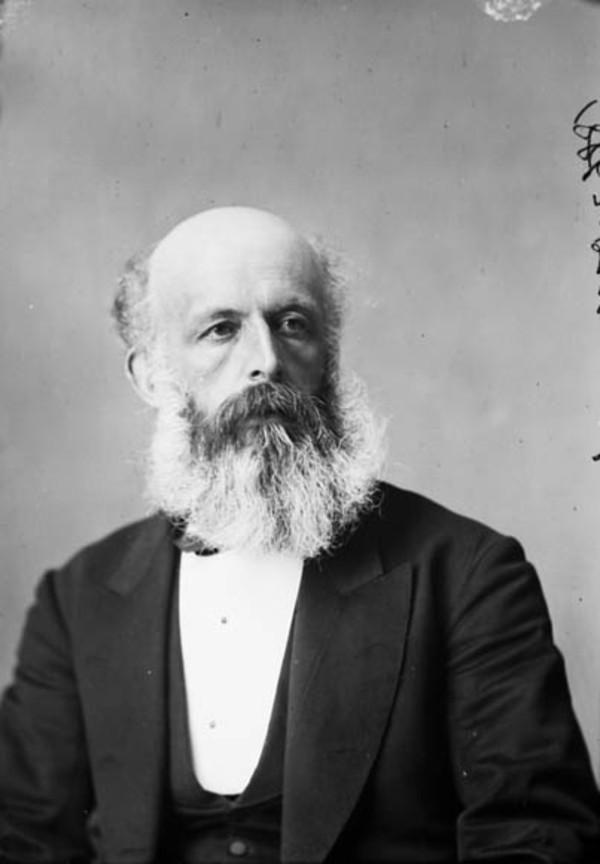

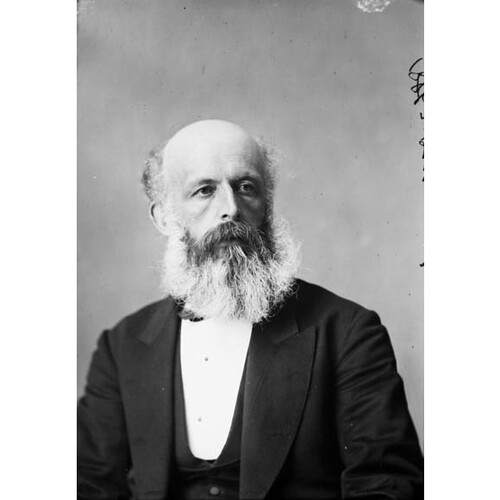

DYMOND, ALFRED HUTCHINSON, journalist, politician, civil servant, and educator; b. 21 Aug. 1827 in Croydon (London), England, son of Henry Dymond; m. June 1852 Helen Susannah Henderson (d. 1896) of London, and they had four sons and five daughters; d. 11 May 1903 in Brantford, Ont.

Educated at a Quaker school, Alfred Hutchinson Dymond would eventually leave the Society of Friends, reputedly because of objections to his marriage to an Anglican. In his early years he evidently engaged in “mercantile pursuits.” While on a business trip to Limpsfield, he became interested in the case of a woman accused of poisoning her child. His acquaintance with her trial led to his involvement from 1850 to 1857 with the newly formed Society for the Abolition of Capital Punishment; he was its secretary from 1854. In 1857 he joined the staff of the London Morning Star, a radical newspaper established by the friends of John Bright, another prominent abolitionist. Eventually Dymond became general manager of the paper, a position he would hold until its amalgamation with the London Daily News in 1869. During his time with the Star he promoted Liberal political policies and such organizations as the Emancipation Society, formed to support the North and the anti-slavery movement during the American Civil War. In 1865, in response to the appointment of a royal commission on capital punishment, he published The law on its trial, an account of the personalities, events, and methods of the abolition movement.

In October 1869 Dymond and his family immigrated to Canada and settled in Toronto. According to his obituary in the Brantford Daily Courier, he came at the invitation of the Globe, which he joined. He would work for it as a political writer and editor until 1878. Shortly after his arrival, he began to take part in political affairs, particularly during the Ontario election of 1871 and the dominion election of 1872. In January 1874 he was returned as the Liberal mp for York North. During his four years in the House of Commons, in the administration of Alexander Mackenzie*, he advocated an extension of the franchise, voting by ballot, the use of tariffs for revenue rather than protection, a prohibitory liquor law, the abolition of capital punishment, and a liberal immigration policy. He took a particular interest in criminal law, and was instrumental in the passage of an act in 1878 that allowed those charged with common assault to stand as witnesses on their own behalf.

Defeated in the general election of 1878, Dymond turned his attention to provincial affairs. Reputedly he prepared reports and conducted commissions of inquiry for the government of Oliver Mowat, and took part in the election of 1879, “editing the literature of the campaign, and addressing public meetings.” In 1880 he was appointed to the Ontario agricultural commission, an exhaustive inquiry into the state of agriculture in the province. He had just finished this work when he was asked, in April 1881, to replace John Howard Hunter as principal of the Ontario Institution for the Education and Instruction of the Blind in Brantford. Despite his profession that he was a “novice not only in the work of teaching the blind, but also in that of education generally,” he took on the task willingly and with diligence. The goal of the institution, which had opened in 1872, was to educate youths between 7 and 21 “whose sight is so defective or impaired as to prevent them from receiving education by the ordinary methods,” wrote deputy minister of education John George Hodgins*. “It is not necessary . . . that a youth be totally blind.” One of the biggest obstacles that Dymond had to overcome was the ignorance and indifference of the public, many of whom believed that the blind could not or should not be educated at all and that the school was an asylum for the destitute blind of all ages.

Dymond firmly believed in educating the blind, but primarily for practical ends. He agreed that a good literary education was essential to personal development; he argued, however, that it could not be used to earn a livelihood. Thus, while the curriculum of the institute under his leadership was “about equal” to that of a well-conducted public school, it emphasized industrial training rather than intellectual pursuits. In addition to a range of academic subjects, boys learned willow and rattan work and piano-tuning; girls were taught domestic skills, notably sewing and knitting. During his 22 years as principal, Dymond also introduced lessons on the form and use of objects, systematic physical exercise, a kindergarten program, cooking classes for the girls, and typewriting.

Though Dymond focused his efforts on able school-aged children, the disabled, the over-aged, and the mentally handicapped always made up a proportion of those attending the institute. Numerous attempts were made over the years to restrict the entry of the over-aged; among the concerns were discipline and the difficulty of teaching students who varied widely in age and ability. Dymond believed, however, that unless it was obvious that the institute could not help an individual, everyone should be given a chance for betterment. Although he often associated blindness with other physical and mental disorders, he had no means of determining the exact nature or extent of the limitations of applicants to the school. Indeed, it was not until 1893 that the first attempt was made to classify the causes of blindness among the students.

A resident of Brantford throughout his principalship, Dymond was active in the Anglican church as a member of Grace Church, as a delegate to synod, and as chairman of the Huron Anglican Lay Workers’ Association. He died while principal, in 1903, and was interred in St James’ Cemetery, Toronto, where other members of his family had been buried. He was survived by three sons and four daughters, among them Allan Malcolm, law clerk of Ontario’s Legislative Assembly, and Bertha, a medical doctor in Toronto.

Alfred Hutchinson Dymond’s publications include The law on its trial; or, personal recollections of the death penalty and its opponents (London, 1865); “International copyright,” Canadian Monthly and National Rev. (Toronto), 1 (January–June 1872): 288–89; “The duration of the Legislative Assembly,” Rose-Belford’s Canadian Monthly and National Rev. (Toronto), 2 (January–June 1879): 470–86, also issued in pamphlet form as Duration of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario (Toronto, 1879); and Ontario Institution for the Education and Training of the Blind; where it is! what it is! and what it does! (Brantford, Ont., 1894); subsequent editions of this last work were published in Brantford under the title Ontario Institution for the Education and Instruction of the Blind . . . around 1898 and in 1902.

AO, RG 22, ser.322, no.2673; RG 63, A-11. St James’ Cemetery and Crematorium (Toronto), Burial records, lots 43–46, section X north. Daily Courier (Brantford), 11 May 1903. Globe, 12–14 May 1903. Toronto Daily Star, 11 May 1903. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1874–78. Canadian album (Cochrane and Hopkins), 1: 435. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). D. D. Cooper, The lesson of the scaffold: the public execution controversy in Victorian England (London, 1974). CPG, 1874–78. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. Dominion annual reg., 1878–86. Ont., Legislature, Sessional papers, annual reports upon the Ontario Institution for the Education of the Blind, 1882–1902/3. Margaret Ross Chandler, A century of challenge: the history of the Ontario School for the Blind (Belleville, Ont., 1980); From darkness to light: the early development of the education of the blind (Brantford, 1979).

Cite This Article

Nancy Kiefer, “DYMOND, ALFRED HUTCHINSON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dymond_alfred_hutchinson_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dymond_alfred_hutchinson_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Nancy Kiefer |

| Title of Article: | DYMOND, ALFRED HUTCHINSON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |