Source: Link

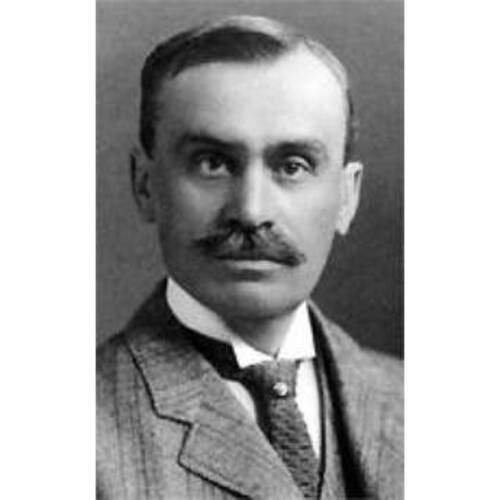

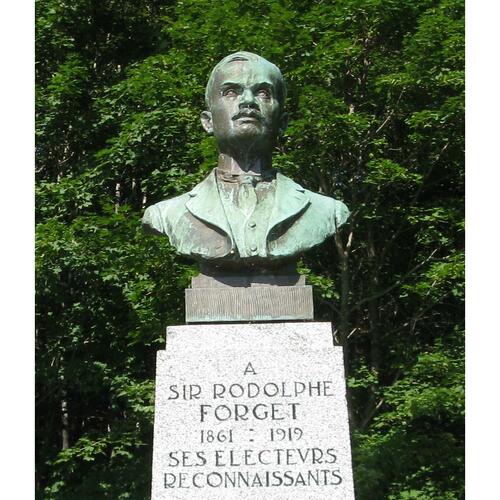

FORGET, Sir RODOLPHE (baptized Joseph-David-Rodolphe), businessman, politician, and philanthropist; b. 10 Dec. 1861 in Terrebonne, Lower Canada, son of David Forget and Angèle Limoges; m. first 12 Oct. 1885 Alexandra Tourville (d. 1891) in Montreal, and they had one daughter; m. secondly 3 April 1894 Blanche McDonald in Rivière-du-Loup, Que., and they had three sons and one daughter; d. 19 Feb. 1919 in Montreal.

One of the more controversial figures of the early 20th century in Canada, Rodolphe Forget was president and director of several of the country’s most important commercial and industrial enterprises. With an extensive network of political and financial contacts, he pioneered major initiatives in transportation and banking and he played a key role in the evolution of the hydroelectric industry in Montreal and Quebec City. His financial and political activities were often intertwined and frequently the subject of considerable public attention.

The origins of the Forget family can be traced back to the middle of the 17th century when Nicolas Forget (Froget, dit Despatis) of Normandy arrived in the district of Montreal. For the most part the Forgets settled in Terrebonne, Repentigny, Lachenaie, and Saint-François-de-Sales (Laval). The parents of Rodolphe, David, a lawyer, and Angèle, half-sister to Louis-Olivier Taillon*, later premier of Quebec, ultimately took up residence in Terrebonne, where they had four children. An only son, Forget commenced classical studies there at the Collège Masson. At age 15, he began an apprenticeship in the brokerage house of his uncle Louis-Joseph Forget. On completing his studies he was employed at L. J. Forget et Compagnie, which, during the 1880s, emerged as the most important brokerage firm in Montreal and gained recognition throughout Canada and abroad. The firm is said to have handled important investments for the Roman Catholic Church of Quebec. In 1890 he became a partner in the firm. It was his involvement in the Montreal Stock Exchange, however, beginning at about the same time, which apparently accounted for his rapid rise in the business community.

The personalities and styles of Louis-Joseph and Rodolphe Forget were said to have complemented each other in their respective approaches to business. Louis-Joseph was described as balanced and prudent in his dealings, whereas Rodolphe was spontaneous, daring, and self-assured. In 1910 Saturday Night stated that “what [Rodolphe] Forget will cheerfully undertake in the stock market would make the average broker stand aghast.”

During the rapid expansion in industrial activity in Canada near the turn of the century the Forgets began investing in newly developing sectors of the economy. With his purchase of shares in the Royal Electric Company in 1890, Rodolphe entered the hydroelectric industry in earnest. Established in 1884, the company appeared to be in good standing as a result of important contracts for the lighting of streets in Montreal. An effort to widen its activities and increase its capital had invited the financial participation of new investors. Among them were the Forgets, who by 1898 controlled almost 50 per cent of the company’s stock. The following year the Forgets and some associates acquired control of the company.

In 1900 the operations of the Royal Electric Company grew substantially, in large part owing to contracts signed with the cities of Longueuil, Saint-Laurent, and Outremont, as well as to an agreement to furnish electricity to the Montreal Street Railway. The firm purchased the Chambly Manufacturing Company, which had a generating station on the Richelieu. In December 1900 Royal Electric sold the industrial side of its operations, its workshops, machines, patents, and manufacturing rights, to the Canadian General Electric Company in order to concentrate on the production and sale of electricity for domestic consumption. It was to receive shares in CGE worth $440,000 in exchange. Forget was in a strong position to obtain ratification of the deal since he possessed or had procurations on behalf of his clients for approximately 90 per cent of the shares in Royal Electric. Six months later the company sold its shares in CGE for over $605,000.

In a move to eliminate competition for the sale and distribution of electricity in Montreal, Forget entered into negotiations with Herbert Samuel Holt* of the Montreal Gas Company. Holt welcomed a merger on the condition that he assume the presidency of the new corporation. With the capitalization of the proposed company estimated at about 17 million dollars, many members of the Montreal Stock Exchange were concerned about its feasibility. Louis-Joseph Forget urged his adventurous nephew to be cautious. On the successful completion of the merger, Rodolphe assumed the second vice-presidency of the new enterprise. (In addition, he was president of one of the merging companies, Royal Electric.) Although the merger had arisen in large measure from the actions of Rodolphe, Louis-Joseph played a critical role in the transaction, bringing together the diverse interests involved. During the first decade of the 20th century, the majority of shares of the Montreal Light, Heat and Power Company were controlled by the Forgets and L. J. Forget et Compagnie. From a financial standpoint, the merger proved to be a success. In an effort to gain control of the entire sector, the firm proceeded to absorb some of the remaining companies involved in the distribution of hydroelectricity in Montreal. By 1909 Rodolphe would begin to sell his shares in the Montreal Light, Heat and Power Company and in 1917 he would relinquish his position as second vice-president.

As early as 1907 Forget was rated a millionaire by the Montreal Daily Star. At a time when Canadian business was dominated almost entirely by Anglo-Saxon capital, he was one of the rare French Canadians to penetrate the élite. The Courrier du Canada (Québec) described him as one of the most powerful men in financial circles, a man who could make and unmake and was seldom beaten in a financial battle. Labelled “the young Napoleon of St. François Xavier Street” for his work on the Montreal Stock Exchange, he served as its chairman from 1907 to 1909.

Following the near-consolidation of the Montreal market in hydroelectricity, Forget had shifted his attention to railways and hydroelectricity in the region of Quebec City. At the turn of the century he already had significant railway holdings there. In 1904, during his successful campaign to represent Charlevoix in the House of Commons, he promised to build a railway between Quebec City and La Malbaie. For his constituents, access to Quebec City was difficult. As the shipping season came to an end each winter, economic activity abruptly halted. Forget looked to remedy this situation by extending an existing line from Quebec City to Saint-Joachim as far as La Malbaie. He considered the Quebec and Saguenay Railway, incorporated in 1905, only the beginning of a line that would eventually run along the north shore of the St Lawrence through Labrador and would facilitate transatlantic travel. In describing the project to potential investors he claimed that the regions to be serviced by the railway were among the richest in the province and offered significant possibilities in the development of forest products.

Despite this favourable description, the Quebec and Saguenay line was a difficult project which required considerable amounts of capital; it ultimately experienced major financial problems. As its troubles grew, Forget moved to merge it with his hydroelectric interests in Quebec City. In effect, he attempted to adopt a model similar to that established by the Montreal Light, Heat and Power Company.

Forget had begun the expansion of his operations in Quebec City with the purchase of the Quebec Gas Company from a group of Toronto financiers in 1909. Along with James Naismith Greenshields*, who owned the Frontenac Gas Company, Forget created in November of the same year the Quebec Railway, Light, Heat and Power Company. Often referred to as the Quebec merger or Le Merger, it involved a number of enterprises in which the Forgets had important investments, including the Quebec and Saguenay Railway Company, the Quebec Eastern Railway Company, the Canadian Electric Light Company Limited, and the Quebec Jacques-Cartier Electric Company. Among the other companies in the merger were the Quebec Railway, Light and Power Company and the Quebec County Railway Company. At the inaugural meeting of the board of directors in March 1910 the number of shares held by Forget placed him in the dominant position, permitting him to assume the presidency. Some of the firm’s administrators came from the gas and electric industries; others were interested in the company’s small railway lines, many of which were financially supported by the federal and provincial governments. Domestic consumption of electricity in Quebec City was far less significant than in Montreal and the profitability of this sector was limited. Moreover, by 1912 the Quebec merger faced competition from the Dorchester Electric Company. Supported by the mayor of Quebec City and several members of the city council, this company had as one of its main objectives the elimination of the monopoly held by Forget. Much of the capital for Dorchester Electric came from one of Forget’s principal rivals, the Montreal brokerage firm of Louis de Gaspé Beaubien*. In 1915 Dorchester Electric, almost bankrupt, was taken over by the Shawinigan Water and Power Company, which created the Public Service Corporation of Quebec to replace the ailing firm. Forget’s merger found a formidable rival in this new company, and would eventually be absorbed by it in 1923. But perhaps the main threat directed at both the merger and the overall business operations of Forget stemmed from the efforts of his political opponents to obstruct his access to overseas capital.

Before World War I, London was the principal source of investment capital for Canadian businessmen. Indeed, some argued that this situation was an impediment for French Canadian enterprises. Forget believed that it was useful to diversify sources of capital and he looked to the French financial market for help. He had established an important network of French investors to support his projects in Quebec City. While doing so, he maintained contact with the British market, cognizant of its continued influence on the Canadian economy.

In 1904 Forget had seriously considered the idea of breaking with L. J. Forget et Compagnie and pursuing his own brokerage operations. A few years later, when Jack Ross, the only son of James Ross, attempted unsuccessfully to compete with the Forgets for brokerage business in Montreal, Rodolphe acutely embarrassed the younger Ross. His actions contributed to the outbreak of a major conflict between James Ross and Louis-Joseph Forget and resulted in some deterioration in the relationship between the two Forgets. Rodolphe left L. J. Forget et Compagnie in August 1907.

After separating from the firm, Forget oversaw the establishment of a brokerage house in Paris which was successful in attracting investment for Canadian firms. For many years he had wanted to create a banking institution in Canada drawing on investment from France. Under the Liberal administration of Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Forget, a Conservative mp, attempted unsuccessfully to obtain a licence for the initiative, but with the election of the Conservatives under Robert Laird Borden* in 1911, he was able to obtain it. That year the Banque Internationale du Canada was created and a potentially important step was taken in enhancing the financial relationship between France and Canada. The BIC appeared to do a flourishing business until August 1912 (a period of 10 months). By then, a power struggle had broken out between its French and Canadian investors and when news of the dispute began to circulate depositors became anxious about the security of their investments. As the situation deteriorated, the group around Forget, which included Conservative mp Robert Bickerdike* and financier Greenshields, looked to protect their own interests.

Forget’s political and business rivals converged on him at a particularly difficult period. Growing increasingly concerned about rumours emphasizing the highly speculative character of the Quebec merger, French investors sent a representative to the province to examine the state of their holdings. A number of newspapers in France began to reproduce local articles about Forget’s business dealings. By far the most damaging of them had appeared in Le Soleil (Québec), a Liberal newspaper whose editor was Henri Lefebvre* d’Hellencourt. Originally from France, d’ Hellencourt was concerned about the image French Canadians would have in the French financial market once investors understood the speculative nature of Forget’s activities. Beginning on 30 Oct. 1912 he systematically attacked both the Quebec merger and the BIC and called for the creation of a royal commission of inquiry to look into Forget’s business practices. He accused Forget of reaping exorbitant profits from the sale of the bank’s stock and questioned the legality of some of his actions. In the case of the Quebec merger, he described the strategy adopted by Forget as “the merciless exploitation of the citizens of Quebec, [who,] without recourse, are condemned to be bled to death to furnish the necessary funds for this merger.” Much of the response to d’Hellencourt’s charges was published in the Conservative newspaper La Patrie (Montreal), of which Forget was a principal financial supporter. One of his main defenders, Conservative mp David-Ovide L’Espérance*, emphasized Forget’s “good reputation and honesty,” which were universally established and recognized.

Notwithstanding efforts to protect Forget’s reputation, several of his projects were in serious financial difficulty. His East Canada Power and Pulp Company, which was to furnish most of the freight for the Quebec and Saguenay, was declared bankrupt in mid December 1912. The BIC was taken over late in the same year by the Home Bank of Canada, which purchased the shares of French investors. The demise of the BIC proved to have important financial and political repercussions for Forget, since French investors were badly shaken by the experience. In the House of Commons Liberal mp Rodolphe Lemieux* went so far as to conclude that because of Forget’s activities “the name of Canada has been besmirched in France and it will take years and years before the good name and reputation of the Dominion stands as high among the financial men of France as it should stand in the eyes of the financiers of all countries.” The failure of the BIC was in no small part due to d’Hellencourt’s campaign, said to be inspired by a number of federal Liberals. The Quebec and Saguenay Railway, not yet completed, was in trouble and Forget appealed to the federal government for help. A bill passed in 1916 authorized the sale of the railway to the government, although the transaction was not finalized until three years later.

Another major transportation project in which Forget was involved was the Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company. A group of businessmen under the presidency of his uncle had obtained control of this important company in 1894 and in 1904, after ten years as a director, Forget became president. Under him, the company sought to expand its operations by establishing a terminal in Toronto and a larger steamer for the Montreal-Quebec line. To finance the expansion Forget went to the Conservative government for permission to issue additional stock. The Liberal opposition expressed concern about the mergers taking place in the transportation industry and the possibility of increased rates as a result of the monopolistic conditions created. Suspicious of Forget, the Liberals attacked the request, but their attempt to prevent the issue of additional stock failed. Because of their involvement in the Richelieu and Ontario, both Rodolphe and his uncle had promoted the development of tourist destinations. The firm constructed a hotel at Tadoussac and in 1899 at Pointe-au-Pic (La Malbaie) it built the famous Manoir Richelieu. The first luxury hotel of that name, the Manoir Richelieu was destroyed by fire in 1928; reconstruction of the facility that still dominates the Charlevoix region started the following year.

Forget was involved in numerous other enterprises. He served as president of the Eastern Canada Steel and Iron Works and the Mount Royal Assurance Company and as vice-president of the Canadian Securities Corporation and the Société d’Administration Générale. He participated in the formation of the Canada Cement Company and in the syndicate which brought together the feuding Dominion Iron and Steel Company Limited and the Dominion Coal Company Limited in 1910 [see James Ross].

Forget identified himself as an independent Conservative who supported the party’s philosophy but allowed for the possibility of deciding an issue on its merits. First elected to the House of Commons for Charlevoix in 1904, he continued to serve the riding until 1917. Following his re-election in 1908, he divided his time between the house, his business interests in Montreal, and his political activities in Charlevoix. He was elected for both Charlevoix and Montmorency in 1911 – said to be the first time a member previously in opposition was elected for two constituencies. That year, with the election of the Conservatives under Borden, his inclusion in the federal cabinet was given serious consideration, but a controversy arose regarding his appointment as minister without portfolio. The nationalist faction of the Borden administration, in particular Frederick Debartzch Monk, was fiercely opposed to the idea, as was nationalist mla Armand La Vergne*, who had campaigned vigorously for the federal Conservatives during the election. Whether their opposition was decisive is not known. One story suggests that Forget refused the post so as to permit the appointment of a representative of the English Protestants of Quebec, George Halsey Perley*. It has also been suggested that Forget was refused admission to cabinet in order to avoid any conflict of interest arising out of his request for a licence for the BIC. Whatever the case, Borden recalled that “there was a movement in favour of Rodolphe Forget but for certain reasons, I thought it undesirable that he should enter the Government.” Shortly thereafter, on 1 Jan. 1912, Forget was made a knight bachelor.

Most of Forget’s speeches in the House of Commons were related to his controversial business dealings, but he did participate in some debates on questions of national interest. He was in favour of the creation of more than one province in the North-West Territories. He viewed positively the extension of railways into the west and agreed that the federal government, rather than the provinces, should maintain control of lands there, since the dominion treasury had already spent millions of dollars on immigration. Why, he asked, “should we leave [ownership of the lands] to these provinces which have been developed with the money of the whole country?”

Although Forget proposed to limit provincial control over public lands, he supported provincial autonomy in educational matters. The Conservative leadership had taken up the cause of provincial rights and demanded that the new provinces be given full control over education. Forget would have preferred guarantees for separate Roman Catholic schools in the western provinces as in Ontario and Quebec. The Catholic minority of the former territories, he believed, could not expect to procure such guarantees from the generosity of the majority and in consequence, “they must take what they could get.” Forget expressed the hope that in future one of the western provinces would have a Catholic majority so as to prove which of the religious groups was more respectful of minority rights. He regretted the tendency among certain politicians to excite French against English, Catholics against Protestants, and province against province. “We are all Canadians in spirit as well as in fact,” he stated. He described relations among Quebec’s Catholics and Protestants as harmonious and suggested that religious differences did not interfere with the understanding between the two groups, which interacted frequently in both politics and business.

Forget was described as being at once a Conservative and a Quebec nationalist whose patriotism was none the less sincere. He understood well the importance of the imperial connection. In the years leading up to World War I, with the growing threat from Germany of military aggression against France and Britain, he used his influence in an attempt to persuade Canadians, and particularly French Canadians, to assist the two countries. He supported a direct contribution to the imperial navy, a position which attracted much attention because of the widespread anti-imperialist sentiment in Quebec. Seeking to strengthen Quebec’s connection with France, he published a series of articles in La Patrie in which he stressed the need to act against the common enemy confronted by Britain and France. He reaffirmed that by helping Britain, French Canadians would also be helping France. When war was declared, he paraded with the 65th Regiment, of which he was honorary colonel. As the war continued, Borden believed that the best way to obtain sufficient recruits for the Canadian forces was to impose compulsory military service. Forget was opposed to the measure and his retirement from politics coincided with Borden’s formation of a coalition government favourable to conscription.

A member of numerous social and sporting clubs, as well as of the Montreal Military Institute, Forget occupied official positions in many of these organizations. He was also active in a number of charitable projects. One newspaper described him as “the friend of the poor and the afflicted, the aged and the infirm. For their welfare and relief, he gives unsparingly. In Charlevoix as in Montreal, he has encouraged and supported innumerable good works.” Since he was said to be discreet about his charitable contributions, the full extent of his generosity is difficult to ascertain. Others noted that he had a habit of withdrawing from a charity as quickly as he became involved. Perhaps his most important philanthropic contribution went towards the construction of a new building for the Notre-Dame Hospital in Montreal. A life governor of the institution and long-time member of its board of directors, Forget went to the archbishop of Montreal to seek assistance for the project. Informed that Notre-Dame was not considered a priority for the archdiocese at that time, Forget decided to promote the project and in 1904 he gave the hospital’s corporation property worth $28,000. His contributions from 1906 to 1918 would total about $250,000.

Forget’s involvement in the region of Charlevoix went beyond his business interests and his political activities. In 1901 he had a sumptuous villa, Gil’Mont, constructed at Saint-Irénée (Saint-Irénée-les-Bains). Its 16 bedrooms often accommodated visiting dignitaries and its dining hall comfortably sat 25. The estate included a prosperous farm, greenhouses, and a pavilion containing an indoor swimming-pool, a billiard-room, and a bowling-alley. In his will, Forget left substantial sums for the upkeep of the estate so that his family could continue to spend its summers there. The villa was destroyed by fire in 1965.

With his family Forget worshipped in the Roman Catholic faith. He founded a school at Saint-Irénée and had the Sisters of Charity of St Louis, a French teaching order, staff it. This convent, maintained entirely at Forget’s expense, existed for almost a decade and taught several hundred pupils. The ecclesiastical authorities and the local priest were especially displeased with Forget’s initiative. Because of their opposition, the school was eventually forced to close and the nuns left.

Of his first marriage Forget had one child, Marguerite. After the death of his first wife, he married Blanche McDonald, the daughter of Alexander Roderick McDonald, district superintendent of the Intercolonial Railway. They had three sons, Gilles, Maurice, and Jacques, and one daughter, Thérèse*, a well-known feminist and politician. Like her husband, Lady Forget was involved in philanthropic activities. She was a director of the Montreal Day Nursery and the Notre-Dame Hospital and was president of the Institution des Sourdes-Muettes of Montreal.

Sir Rodolphe Forget’s influence on the Canadian political and business scene of the period remains inestimable. He died on 19 Feb. 1919, leaving behind him, at the age of 57, an extraordinary legacy.

AC, Montréal, Cour supérieure, déclarations de sociétés, 15, no.470 (1890); 27, nos.23 (1907), 603 (1907), 616 (1907), 617 (1907); Rivière-du-Loup, État civil, Catholiques, Saint-Patrice, 3 avril 1894. ANQ-M, CE1-33, 12 oct. 1885; CE1-51, 16 févr. 1891; CE6-24, 10 déc. 1861. Gazette (Montreal), 20 Feb. 1919. Montreal Daily Star, 20 Feb. 1919. Le Soleil, 30 oct.–30 déc. 1912. J. C. A., “Rodolphe Forget: merger specialist and crackerjack financier,” Saturday Night, 26 Nov. 1910: 19. W. H. Atherton, Montreal, 1534–1914 (3v., Montreal, 1914). R. C. Brown and Ramsay Cook, Canada, 1896–1921: a nation transformed (Toronto, 1974). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1904–17. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). CPG, 1904–17. Thérèse F[orget] Casgrain, A woman in a man’s world, trans. Joyce Marshall (Toronto, 1972). [Jacqueline] Francœur, Trente ans rue St-François-Xavier et ailleurs (Montréal, 1928). Denis Goulet et al., Histoire de l’hôpital Notre-Dame de Montréal, 1880–1980 (Montréal, 1993). Roger Graham, “The cabinet of 1911,” in Cabinet formation and bicultural relations: seven case studies, ed. F. W. Gibson (Ottawa, 1970), 47–62. Clarence Hogue et al., Québec: un siècle d’électricité (Montréal, 1979). Elisabeth Naud, “La villa de Rodolphe Forget, Gil’Mont à Saint-Irénée-les-Bains,” Cap-aux-Diamants (Québec), no.33 (printemps 1993): 29–32. Newspaper reference book. Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec. Pierre Savard, Le consulat général de France à Québec et à Montréal de 1859 à 1914 (Québec, 1970). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). The storied province of Quebec; past and present, ed. William Wood et al. (5v., Toronto, 1931–32).

Cite This Article

Jack Jedwab, “FORGET, Sir RODOLPHE (baptized Joseph-David-Rodolphe),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/forget_rodolphe_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/forget_rodolphe_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jack Jedwab |

| Title of Article: | FORGET, Sir RODOLPHE (baptized Joseph-David-Rodolphe) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |