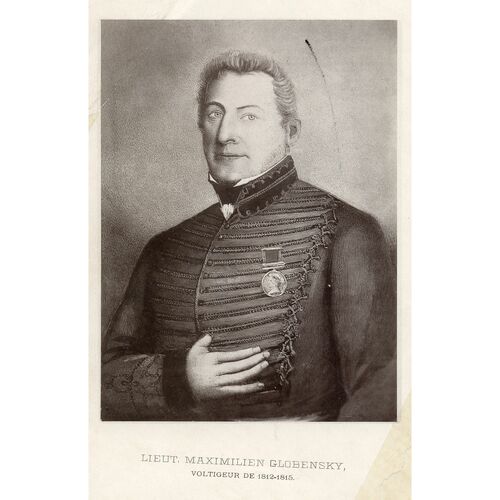

GLOBENSKY, MAXIMILIEN, soldier, b. 15 April 1793 at Verchères, Lower Canada, son of Dr Auguste-France Globensky, of Polish extraction, and Marie-Françoise Brousseau, dit Lafleur de Verchères; m. first Élisabeth Lemaire Saint-Germain, by whom he had four daughters and one son, and secondly Marie-Anne Panet on 3 March 1851 at Sainte-Mélanie; d. 16 June 1866 at Saint-Eustache, Canada East.

Maximilien Globensky is remembered because of his participation in the War of 1812 and the disturbances of 1837 at Saint-Eustache. He enlisted in the Canadian Voltigeurs during the war with the United States, and took part in the battles of Châteauguay, Lacolle, and Ormstown. On Lieutenant-Colonel Charles-Michel d’Irumberry* de Salaberry’s recommendation, he was given the rank of 2nd lieutenant on 24 March 1813 for recruiting 12 men. When peace was restored, he was promoted 1st lieutenant on 8 Feb. 1815. He was also granted half pay, which he continued to receive until his death, and 500 acres of land in Buckingham County. This grant he was able to exchange for other land in the Plantagenet Township, Upper Canada. On 11 Dec. 1826 he became a captain in the 1st militia battalion of York County, Lower Canada. Ten years later, on 12 April 1836, he acquired 933 acres in Drummond County.

On 27 Nov. 1837, only a few days after the battles of Saint-Denis and Saint-Charles, the military authorities asked Globensky to raise 60 volunteers, and entrusted him with command of the group. According to his son Charles-Auguste-Maximilien, Globensky recruited his men from “the most highly regarded, the most respectable and the most comfortably off” citizens of Saint-Eustache. On 14 Dec. 1837, when the British soldiers opened fire on the Patriotes at Saint-Eustache, these volunteers were stationed on an island opposite the village, blocking the escape of fugitives across the frozen surface of the Rivière des Mille-Îles. The next day Globensky was instructed by Sir John Colborne to maintain order at Saint-Eustache after the defeat of the Patriotes and the departure of the regular troops for nearby Saint-Benoit.

If his son is to be believed, Globensky cannot be held responsible for the abuses committed at Saint-Eustache. On the contrary, reports his son, despite his family’s hostility towards the Patriotes and the differences of his sister Hortense* with some of them, his attitude towards them was kindly and he also sought to protect them from needless cruelty, for example by preventing soldiers and volunteers from outside the area from totally destroying the village. But there are no documents bearing specifically on his attitude during these dark hours except the favourable testimony collected by his son. There is no doubt, however, that volunteers of Maximilien Globensky’s company did take part in the depredations. According to Colborne, the officials of Saint-Eustache and Rivière du Chêne were the perpetrators of the destruction. It is true that the commander-in-chief thus relieved his regulars of all responsibility. Although Colborne’s argument concerning the desire for revenge on the part of the local pro-government faction is not without logic, one must remember that Globensky’s son himself admitted that some volunteers under his father’s orders might have carried out reprisals.

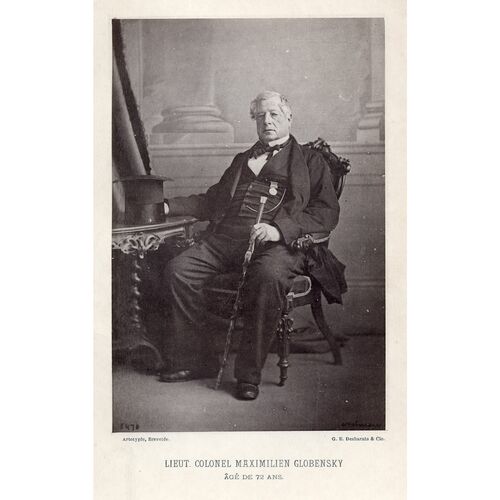

In any case, Globensky’s assistance was appreciated by the government, since on 4 Nov. 1838 he was asked to raise a group of volunteers to counter the insurrection of the Hunters’ Lodges. Meanwhile he had acquired 200 acres in Arthabaska County. On 12 Sept. 1845 Maximilien Globensky ended his career in the Lower Canadian militia with the title of lieutenant-colonel. He was still prepared for military duty towards the end of his life, since he offered his services to the government in the 1860s when the Trent affair and the threat of a Fenian invasion aroused fears of an armed conflict with the American republic.

Globensky always thought of himself as a soldier, but evidence from one document suggests that he may have engaged in business of some kind during the quiet years he spent at Saint-Eustache. His motto, “God and my King,” reveals the convictions of a soldier who always discharged his duties with dignity. Some years after his death in 1866, he was attacked for having taken up arms against the Patriotes by political opponents of his son, who was elected as a Conservative in the 1875 by-election in the county of Deux-Montagnes. Charles-Auguste-Maximilien then undertook to defend his father’s memory in La rébellion de 1837 à Saint-Eustache, which he finished in 1877 but did not publish until 1883. His interpretation of 1837 roused the wrath of Laurent-Olivier David* and a sharp and interminable controversy ensued in La Minerve and La Patrie about the meaning of the 1837 rebellion and of the events at Saint-Eustache.

ANQ-M, État civil, Catholiques, Saint-François-Xavier-de-Verchères, 15 avril 1793. PAC, MG 8, G29, 15, p.5487; RG 1, L3, 93, pp.46243–45; RG 8, I (C series), 1, p.28; 187, p.117; 797, p.83; 798, p. 23; 1039, pp. 15, 123, 125, 165; 1170, p.154; 1172, p.111; 1202, pp. 19, 31, 39; RG 9, I, A5, 5; 14, p.273. PRO, CO 42/280, p.260. Charles Beauclerk, Lithographic views of military operations in Canada under His Excellency Sir John Colborne during the late insurrection (London, 1840). La Minerve, 23 juin 1866. Quebec Gazette, 18 Dec. 1837. Langelier, List of lands granted. Liste de la milice du Bas-Canada, pour 1829 (Québec, [1829]). Mariages du comté de Joliette (du début des paroisses à 1960 inclusivement), Lucien Rivest, compil. (4v., Montréal, 1969), II. Émile Dubois, Le feu de la Rivière-du-Chêne; étude historique sur le mouvement insurrectionnel de 1837 au nord de Montréal (Saint-Jérome, Qué., 1937). [C.-A.-M. Globensky], La rébellion de 1837 à Saint-Eustache précédé d’un exposé de la situation politique du Bas-Canada depuis la cession (Québec, 1883). Ludwik Kos-Rabcewicz-Zubkowski, Les Polonais au Canada (Ottawa et Montréal, 1968), 12, 14–17, 48, 50, 53, 162. The Polish past in Canada; contributions to the history of the Poles in Canada and of the Polish-Canadian relations, ed. Wiktor Turek (Toronto, 1960), 101–22. “Feu M. C. A. M. Globensky,” Le Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe, 14 févr. 1906. Jacques Prévost, “Les Globensky au Canada français,” SGCF Mémoires, XVII (1966), 156–61.

Cite This Article

Jean-Pierre Gagnon, “GLOBENSKY, MAXIMILIEN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 8, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/globensky_maximilien_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/globensky_maximilien_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean-Pierre Gagnon |

| Title of Article: | GLOBENSKY, MAXIMILIEN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | February 8, 2026 |

![Lieut. colonel Maximilien Globensky, âgé de 72 ans [image fixe] / Desbarats & cie Original title: Lieut. colonel Maximilien Globensky, âgé de 72 ans [image fixe] / Desbarats & cie](/bioimages/w600.3879.jpg)