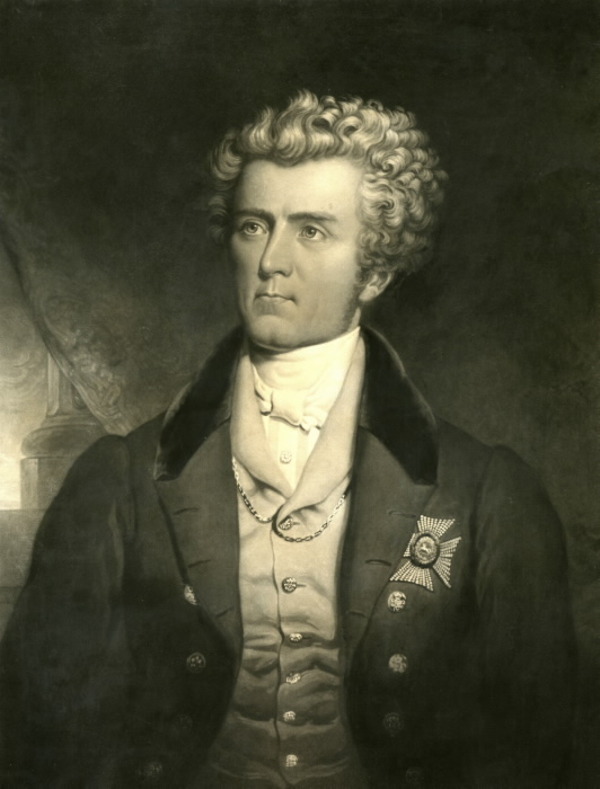

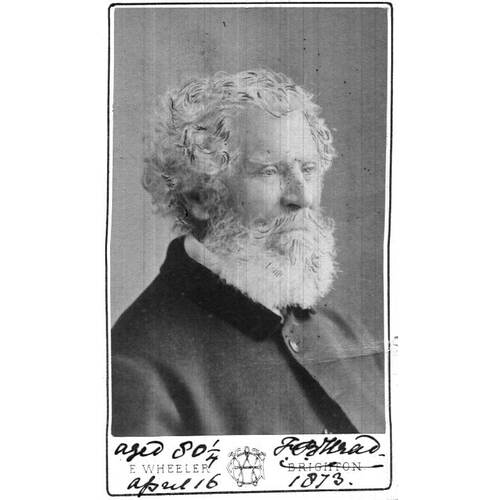

HEAD, Sir FRANCIS BOND, soldier, author, and colonial administrator; b. 1 Jan. 1793, at The Hermitage, Higham, Kent, Eng., son of James Roper Mendes Head and Frances Anne Burgess; m. his cousin, Julia Valenza Somerville, in 1816, and they had four children; d. at his home, Duppas Hall, Croydon, Eng., 20 July 1875.

Francis Bond Head was descended from Dr Fernando Mendes, a Spanish Jew who accompanied Catherine of Braganza to England in 1662 as her personal physician. Francis’ grandfather Moses married Anna Gabriella Head, the heiress of a Kentish gentry family; his father took the Head name on inheriting Anna’s estates.

Francis Head was commissioned a lieutenant in the Royal Engineers upon passing out of the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, in 1811. He saw service in Malta, at Waterloo, and as engineering officer in the Edinburgh garrison, retiring as a major on half-pay in 1825 to take a position as mining supervisor for a company with South American interests. Loss of the company’s concession rendered the expedition a costly failure, for which Head indicted his employers in Reports relating to the failure of the Rio Plata Mining Association (1827).

Head had already begun in 1826 a lifelong connection with the publishing house of John Murray with Rough notes taken during some rapid journeys across the pampas and among the Andes, a book which reveals his talent for graphic description, his love of nature, his interest in primitive peoples, his deep suspicion of things un-English, his erratic and impulsive bent, and his penchant for self-dramatization. Both his books and his exploits brought him to public notice. He was nicknamed “Galloping Head” for his feat in riding twice across South America between Buenos Aires and the Andes; and his demonstration of the military usefulness of the lasso brought him a knighthood from William IV in 1831. A number of other writings followed, including articles for the Quarterly Review and his most successful book, Bubbles from the Brunnens of Nassau (1834), a travel book of ingratiating superficiality which went through six editions. In 1834 as well he was named assistant poor law commissioner for Kent under the new poor law of that year, a preferment he is said to have owed to Lord Brougham’s influence.

In December 1835 came a more surprising appointment. Head was named to succeed Sir John Colborne* as lieutenant governor of Upper Canada. Lord Glenelg, the colonial secretary, selected Head not because he had confused him with his cousin Edmund Walker Head*, or because of Lady Head’s exalted family connections, but because the strongly reformist members of the cabinet, especially Lord Howick (later 3rd Earl Grey), were convinced by Head’s vigorous administration of the new poor law and his writings on the subject that he was the conciliator needed in Upper Canada. It was for the same reason that the puzzled Head, on his arrival in Toronto in January 1836, found himself welcomed as “a Tried Reformer.” The cabinet had made an astonishing choice. Head had so little political experience that he had never voted in an election; he had displayed no interest whatever in colonial policy; and even his essay on the poor law, though couched in the rhetoric of reform, was based upon the deepest social conservatism.

Head’s first moves as lieutenant governor were promising. Though his publication in full of his instructions from Glenelg embarrassed both the commission under Lord Gosford [Acheson*] in Lower Canada and the home government, and showed his insubordinate attitude towards Glenelg as well as his political innocence, to many Upper Canadians his action seemed an augury of change. Then, after a round of conversations with leading Reformers, Head succeeded in persuading John Rolph* and a reluctant Robert Baldwin*, as well as John Henry Dunn*, the receiver general, to join the Executive Council. Within two weeks, however, Head’s coup led to a crisis when all six councillors formally protested his failure to consult them on all matters relating to the government of the province. Head’s reply, an able document often attributed to Chief Justice John Beverley Robinson*, was constitutionally unassailable. Since, under the Constitutional Act, the lieutenant governor alone was responsible for the conduct of government and was bound to consult his council only on certain specified matters, Head demanded that his councillors either alter their views or resign. They chose to resign, on 12 March, after having held office for three weeks. The Tory members of the council, George H. Markland*, Joseph Wells*, and Peter Robinson*, though now ready to retract, went out with the new councillors, Head arguing that the council must act as a body though he wished also to avoid the unpopularity that a dismissal of the new councillors alone would have brought him.

The controversy between Head and the council had been conducted temperately; the assembly’s reaction, however, was violent. Reformers and Conservatives, with but two dissenting votes, demanded more information from Head on the controversy; on its production a select committee was set up to investigate and report. While it was sitting, the political climate worsened sharply with the disclosure of Colborne’s 11th-hour endowment of 57 Anglican rectories. In consequence the committee’s report, given the house on 15 April, was extremely harsh. Head was termed a deceitful despot whose conduct dishonoured the king he represented. On adopting the report, the assembly voted also to stop supply, thereby depriving government of £7000 for official salaries. Head, deeply angered by the personal attack upon him, reacted disproportionately by reserving all money bills passed during the session and proroguing the legislature. A month later, on 28 May, he dissolved it and ordered writs to be issued for an election.

Head’s pose during these events was that of a man above party, unjustly accused by a faction of partiality to the Conservatives. Far from being captured by the Family Compact, however, he had quite independently made up his mind about the nature of provincial politics almost as soon as he had arrived, and never changed his ideas thereafter. As early as 5 February he had told Glenelg that the Whig policy of conciliation was wrong, that the Reformers – all Reformers – were “The Republican party,” and that their aim was to use responsible government to sever the imperial connection.

His private intention of February of “throwing himself on the good sense and good feeling of the people” was carried out during the most bitter election in the province’s short history, when he campaigned openly against the Reformers. Many factors caused their overwhelming defeat, but Head’s electioneering skill was certainly an important one. His direct and vivid language transformed the complexities of provincial politics into a simple confrontation between the forces of loyalty, order, and prosperity and those of a selfish and disloyal faction. He managed to conjure up the menace of outside intervention (whether French Canadian or American he left unsaid) in support of provincial democrats, and trumpeted, in the name of the loyal militia, “Let them come if they dare!” Such tactics were “not exactly according to Hoyle,” he admitted to Glenelg, “but, Mon Seigneur, do you think that Revolutions are made with Rose water,” he wrote in French. What Head called his “plain homely language” may have astonished the Colonial Office, but gained him “herds of friends.” Conservatives, moderates, and recent immigrants alike responded to his appeals and combined to defeat not only such prominent Reformers as William Lyon Mackenzie*, Marshall Spring Bidwell, and Peter Perry*, but the bulk of their followers as well.

For Head, the result of the election was a vindication of his views, and the year that followed was a relatively quiet and happy period for him. During the summers of 1836 and 1837 he toured the province informally, meeting many settlers, visiting Indian bands, and acquiring the fund of anecdote that gives piquancy to his books on Upper Canada. His relations with his new legislature went smoothly enough, Head encouraging the conservative majority in the assembly in its ambitious programme of public improvement.

But during the same period, Head dissipated much of the moderate support he had gained during the election and at the same time lost the prestige his victory had momentarily given him at the Colonial Office. Dismissing from office a number of men, including Dr William Warren Baldwin* and Judge George Ridout, who had shown Reform sympathies during the election, he embarked at the same time on an extraordinary correspondence with Glenelg in which he urged the abandonment of the policy of conciliation. Although it was plain to Glenelg that Ridout had been unjustly treated, Head refused to reinstate him, nor would he appoint Bidwell to the bench. To Head, Bidwell was a “disloyal man” though he admitted him to be much abler than those raised to judgeships in the province. The strong personal animus Head felt towards Bidwell probably had its origin in the part Bidwell had played as speaker of the Reform assembly. Whatever the reason, Head was so blinded by it that he did not see how valuable a judgeship for Bidwell would have been in cementing the temporary alliance of conservatives and moderates formed during the election campaign. His quixotic response to the bank crisis of early 1837 (he refused to allow provincial banks to suspend specie payments, as banks in the United States and Lower Canada had done) was vigorously attacked in a special session of the legislature called to resolve the crisis. Deadlock between the House of Assembly and the Legislative Council, though eventually broken on Head’s terms, showed the extent to which his popularity had diminished.

Head’s weakening grip upon provincial politics was soon overshadowed by the events that were to lead to armed revolt in December, a revolt for which he has traditionally been held largely responsible. Yet the origins of the rebellion of 1837 lie in political and religious antagonisms that predate his arrival in the province, and with social tensions engendered by the flood of British immigration that was changing the composition of the province’s population. Agrarian economic distress and the swift movement towards revolt in Lower Canada were specific causes of the rebellion in Upper Canada; so too was the personality of Mackenzie. For none of these can Sir Francis be held responsible.

But he was hardly blameless. Although he had not “stolen” the election of 1836 in the corrupt sense alleged by Mackenzie and others, his unprecedented intervention had shattered the old politics and created deep disaffection among a minority; his uncompromising hostility toward Reformers after the election, with the apparent backing of the home authorities, had extinguished for many what hopes they had held for gradual change. More immediately, his deliberate stripping of regular troops from the colony in November 1837 to help Colborne meet the Lower Canadian emergency was most provocative, especially in the light of his foreknowledge of the martial preparations of Mackenzie and his followers. In his Narrative (1839) Head explained that “the more I encouraged [the rebels] to consider me defenceless the better”; he wished “to await the outbreak, which I was confident would be impotent,” in order to prove the loyalty of the mass of the people. As J. B. Robinson remarked upon reading this passage, “any quiet Englishman will be apt to say, that man would make a rebellion anywhere.” Public criticism prompted Head to change his story in The emigrant (1846). There he alleged that Colborne had withdrawn the troops without consulting him, a statement for which there is no foundation. As late as 20 Nov. 1837 Head told Colborne that he was releasing troops to Lower Canada “as nothing more or less than a challenge to the rebels to change agitation into attack,” while at the same time fatuously assuring him (in the face of repeated warnings from Colonel James FitzGibbon* and others) that “nothing can be more satisfactory than the present political state of this province.”

It was precisely the defencelessness of the government that led Mackenzie first to propose, and then, on the night of 4 December, to attempt to carry out an armed coup. When Head was awakened with the news of the revolt, he appears to have been thrown into a state of shock, judging from his erratic and indecisive behaviour in the ensuing days. On 7 December the militia had dispersed the rebels on Yonge Street north of Toronto and Head (like Mackenzie before the battle) indulged his talent for excess by ordering burnt both John Montgomery’s tavern and the home and buildings of David Gibson*, a rebel leader, though at the same time granting immediate clemency to prisoners from the rebel rank-and-file. He had already settled another score by persuading Marshall Spring Bidwell, who was not involved in the revolt, to go into voluntary exile.

After the suppression of armed risings in the province, Head, his confidence restored, threw himself with characteristic energy into the task of supervising the movements of the militia on the frontiers in order to counter the threat posed by Mackenzie and his new-found American adherents. In the midst of these activities he learned, in a dispatch from Glenelg, that the resignation he had proffered some months earlier had been accepted because of his refusal either to reinstate Judge Ridout or to acquaint him with the grounds of his dismissal. Almost the last accomplishment of Head’s administration was the acceptance by the Colonial Office of his recommendation, against the advice of his council, that the special authority under which Thomas Talbot* had for many years controlled settlement in the western part of the province be terminated “without loss of time.”

Head departed Upper Canada convinced that he had saved it for the empire, and for several years tilted unavailingly against the colonial policies of such men as Durham [Lambton*], James Stephen, Lord John Russell, and Sir Robert Peel whom he considered were squandering the fruits of his work. Had Francis Head never come to Upper Canada he would still be remembered as a minor and rather engaging member of the gallery of 19th-century English literary eccentrics; Lord Melbourne, who gave Head an interview on his return from North America, could only reply to his catalogue of grievances by observing, “But Head, you’re such a damned odd fellow.” His selection as lieutenant governor was a singularly unfortunate one, for the implementation of the policy of the Whig government and the state of the province demanded the stabilizing arts of the political healer, not the melodramatics of a literary man turned polemicist with a romantic yearning for the hero’s role.

Head never again held a government post. During the remaining years of his long life, his fluent pen produced a series of books and articles, the mixed and ephemeral character of which is indicated by the following titles: Stokers and pokers (1849), Hi-ways and dry-ways (1849), The defenceless state of Great Britain (1850), A faggot of French sticks, or Paris in 1851 (1852), A fortnight in Ireland (1852), The horse and his rider (1860), Mr. Kinglake and his history of the Crimean War (1863), The life of Field Marshal Sir John Burgoyne (1872), and his collected essays, published in two volumes in 1857.

In confederation year Sir Francis petitioned the cabinet for recognition of the contribution he had made to the development of Canada. On 21 Dec. 1867 Queen Victoria made him a member of her Privy Council, an honour termed by the prime minister, Lord Derby, “a tardy act of justice.”

A complete list of F. B. Head’s works can be found in the British Museum catalogue but the following are of interest here: F. B. Head, Descriptive essays contributed to the Quarterly Review (2v., London, 1857); The emigrant (London, 1846); A narrative (London, 1839), repub. as A narrative with notes by William Lyon Mackenzie, ed. with intro. S. F. Wise (Carleton Library series, no.43, Toronto, Montreal, 1969); Rough notes taken during some rapid journeys across the pampas and among the Andes (London, 1826).

PAC, MG 24, A25 (Francis Bond Head papers); A40 (Colborne papers); RG 5, A1, 160–80; RG 7, G1, 75. PAO, Macaulay family papers; Mackenzie-Lindsey collection; Sir John Beverley Robinson papers; John Strachan papers. PRO, CO 42/429–42/431, 42/437, 42/439, 42/444. Charles Lindsey, The life and times of William Lyon Mackenzie; with an account of the Canadian rebellion of 1837, and the subsequent frontier disturbances, chiefly from unpublished documents (2v., Toronto, 1862), I, 355–401; II, 5–132. [A. E. Ryerson], Sir F. B. Head and Mr. Bidwell . . . (Kingston, U.C., 1838). J. C. Dent, The story of the Upper Canadian rebellion; largely derived from original sources and documents (2v., Toronto, 1885). M. A. FitzGibbon, A veteran of 1812, the life of James FitzGibbon (Toronto, 1894), 184–235. S. W. Jackman, Galloping Head; the life of the Right Honourable Sir Francis Bond Head, bart., P.C., 1793–1875, late lieutenant governor of Upper Canada (London, [1958]). J. A. Gibson, “The ‘persistent fallacy’ of the Governors Head,” CHR, XIX (1938), 295–97. H. T. Manning, “The colonial policy of the Whig ministers, 1830–37,” CHR, XXXIII (1952), 203–36, 341–68. H. T. Manning and J. S. Galbraith, “The appointment of Francis Bond Head: a new insight,” CHR, XLII (1961), 50–52. C. B. Sissons, “The case of Bidwell; correspondence connected with the withdrawal of Marshall Spring Bidwell from Canada,” CHR, XXVII (1946), 368–82. William Smith, “Sir Francis Bond Head,” CHA Report, 1930, 25–38.

Cite This Article

S. F. Wise, “HEAD, Sir FRANCIS BOND,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/head_francis_bond_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/head_francis_bond_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | S. F. Wise |

| Title of Article: | HEAD, Sir FRANCIS BOND |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |