Source: Link

McNAB, ARCHIBALD, 17th Chief of Clan MACNAB, colonizer, justice of the peace, and militia officer; b. c. 1781 in Bouvain, Glen Dochart, Scotland, only son of Robert MacNab and Anne Maule; m. c. 1810 Margaret Robertson, and they had six children, of whom two sons and two daughters survived infancy; he also had at least two illegitimate children; d. 12 Aug. 1860 in Lannion, France.

Until 1760 the Macnab clan of Glen Dochart had managed to weather the political changes of the centuries by close association with the Breadalbane branch of the powerful Campbell family. The 16th chief, Francis (d. 1816), Archibald McNab’s uncle, was a man at odds with his times, living on a lavish scale as an old-fashioned Highland chieftain. He lacked a legitimate heir and Archibald knew from his early years that he was to be “The MacNab.” His education was by Presbyterian schoolmasters; contrary to tradition, it was not completed at the Inns of Court, London, or in Paris. By 1806 he was living in London, well known among the sporting set of the capital as a drunkard, braggart, and whore-master. It was the nephew who introduced the uncle into London society in 1812, a visit which produced many, probably apocryphal, stories. Both were famous for their lack of money and touchy pride, which could degenerate into uncontrolled rage if provoked.

When Archibald succeeded to the Macnab lands in 1816, he inherited an estate mortgaged beyond redemption, and debts of about £35,000 to be met on an annual income of £1,000 from property rentals. Aided by his uncle’s old adviser and companion Dugald MacNab, he spent the next several years trying to stave off the inevitable collapse. Eventually minor creditors combined to secure a foreclosure on his lands and goods, threatening him with imprisonment by a writ of caption. The flight which followed, by way of England to Upper Canada, has a certain epic quality but the fact remains that he fled in disgrace, pursued by bailiffs, abandoning his wife and children in the process. He then proceeded to launch a highly controversial attempt to build a fortune upon the backs of settlers on the frontier of Upper Canada.

McNab arrived in the Canadas in 1822 intent on acquiring a free grant of land in the upper Ottawa valley and importing Scottish settlers, from whose improvements to the land he would profit. His flamboyant style quickly drew public attention. In the winter of 1822–23 articles in the Kingston Chronicle announced his reputed discovery in Glengarry County of the lost sword of Prince Charles, the Young Pretender, which he proposed to present to King George IV. By February 1823 McNab was in York (Toronto) petitioning that Torbolton Township on the Ottawa River be held vacant until the colonial secretary, Lord Bathurst, had reviewed his settlement scheme. Acting on the advice of Lieutenant Governor Sir Peregrine Maitland, who regarded the proposal as risky and a potential embarrassment to the provincial government, Bathurst refused to approve it. In October, however, McNab repeated his petition, expressing the hope of bringing his “people” to settle an unsurveyed township beyond Fitzroy Township. Though willing to be “personally responsible” for their conduct, he insinuated that he could avoid all “possibility of trouble” if he got them to sign indentures in Scotland. Under the agreement he would exact from each settler after three years, in return for his passage, an annual quitrent in the form of a bushel of wheat or its equivalent in flour for each cleared acre.

The petition went before the province’s Executive Council, where the Reverend John Strachan* advised against accepting the scheme because of the danger of “leaving the Settlers & their descendants subject to a perpetual rent charge.” They were not, he reasoned prophetically, “likely to remain content with a burthen which they could not, in any manner, shake off.” Though council saw the weakness of the scheme, it was so anxious to have the land settled that it approved the plan in November 1823. McNab was given a block grant of 1,200 acres at once and 3,800 additional acres later, as well as sole superintendence of the settlement of adjacent lands in the unsurveyed township, which was located at the junction of the Ottawa and Madawaska rivers. Once the settlers had performed the settlement duties required by the province and had met his claims on them for his costs, patents would be issued to them by the crown. The terms were to be explained to the settlers by McNab and embodied in agreements, copies of which were to be deposited in the government offices. He also had to submit a progress report within 18 months. The proposed township was surveyed and named McNab in 1824, the year in which he built Kinell Lodge, a log house at the mouth of the Madawaska.

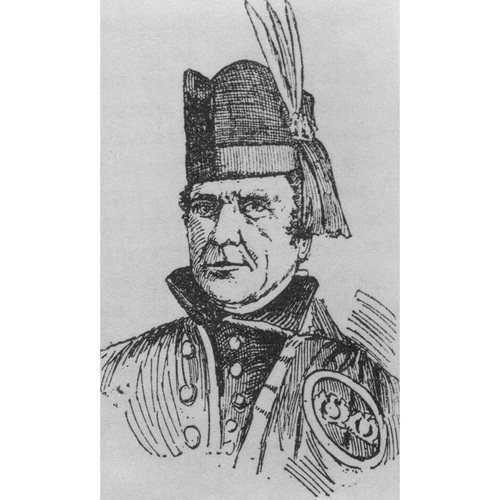

McNab ignored council’s conditions and for the next 15 years attempted to govern the township as his personal property. He was able to operate successfully for so long owing to the illiteracy and initial credulity of the settlers and to the trust and support of friends he had made both in York and in the Ottawa valley, including Alexander James Christie* and Hamnett Kirkes Pinhey. In dealing with settlers and government officials, McNab traded on his image as a chieftain, a trustworthy gentleman, and a frontier benefactor. His colourful but autocratic conduct stood out in the provincial society of Upper Canada. In the late 1820s John Mactaggart*, clerk of works on the Rideau Canal, described him travelling through the colony “dressed always in full Highland costume, the piper going before.” He was, Mactaggart observed, “full of enthusiasm about Scotland: a thing rarely met with amongst people beyond the Atlantic.” Henry Scadding* provides a description of McNab’s visits to York on business, when he usually resided at the home of clansman David Archibald MacNab, brother of Allan Napier MacNab*: “Surrounded or followed by a group of his fair kinsfolk of York, he marched with dignified steps along the whole length of King Street, and down or up to the Kingston Road. . . . the Chief always wore a modified highland costume, which well set off his stalwart, upright form: the blue bonnet and feather, and richly embossed dirk, always rendered him conspicuous, as well as the tartan of brilliant hues depending from his shoulder after obliquely swathing his capacious chest; a bright scarlet vest with massive silver buttons, and dress coat always thrown back, added to the picturesqueness of the figure.” Overbearing and offensive, McNab could also be charming and obliging. Joseph Bouchette*, Lower Canada’s surveyor general, wrote that he had received in 1828 the “characteristic hospitality” of “the gallant chief,” and during a tour of the province in 1836 Lieutenant Governor Sir Francis Bond Head* planned a special visit with McNab at Bytown (Ottawa). In such social situations few, if any, ever saw his sordid side.

His thorough dishonesty in the Canadas began with the agreements concluded with his settlers, the first group of whom arrived from Scotland in 1825. They were made to acknowledge by deeds the excessive amounts charged but never fully expended by McNab for their passage to McNab Township. It is uncertain how many families he actually brought in. In 1839 he claimed to have paid the way for 29 families from Scotland and 36 families, of mixed national backgrounds, enlisted at Montreal. Yet of the 142 families then living in McNab, no more than 12 admitted to having come at his expense. Despite his interest in establishing his patriarchal control as a clan head, his system of quitrents was antiquated and untenable, and many settlers fell behind. His neglect of the township became notorious. Where there was progress before 1840, it was achieved by the settlers without contribution from McNab. Still, it would be difficult to prove that his unhappy rule retarded agricultural development, for cultivated acreage in the township rose by 65 per cent between 1840, when his power was at its height, and 1844, when he departed, by which time land grants in McNab were being made by the province in a fair and equitable manner.

McNab’s downfall, though slow in coming, was engineered partly by his own folly in pursuit of greater financial return and partly by the capacity of the settlers to work together to apply pressure on the government. Trouble began as early as 1829 when 15 heads of families brought out from Scotland by McNab petitioned Lieutenant Governor Sir John Colborne* for help in having their agreements with McNab declared null and void. Now that they were “a little acquainted with the country, the usages and customs of the country and the nature of the soil,” they found themselves saddled with a “grievous burden which none of his Majesty’s subjects in this province are under or able to bear.” The following year the government appointed Alexander McDonell*, crown lands agent for the Newcastle District, to investigate the township. Though he found that the settlers were unable to proceed with their clearances and could not supply the amount of wheat or flour demanded by their engagements, the government saw no reason to intervene.

The chief’s inflexible nature led him to pursue many settlers for payment of arrears in the district court at Perth, a process facilitated by his powers as a justice of the peace since 1825. He used breach of covenant as the usual accusation. McNab frequently had proceedings drawn out, necessitating repeated trips to Perth, an entanglement which proved a considerable hardship for the settlers. His run of success in the court ended in 1835, at which time his attention turned to another source of revenue. He offered to give up his claim to the 5,000 acres he had acquired in the 1820s in return for the right to cut or collect duties on the pine timber on unlocated lots in McNab. He claimed that little of the township’s land was “fit for cultivation,” so that if he was “to provide for his countrymen” – a typically perverse twist to the facts – he would need alternate income. His request was granted in 1836, despite Attorney General Robert Sympson Jameson’s concern that such an arrangement would form a “permanent obstacle” to the settlement of the lots affected. The grant sanctioned something McNab had been doing illegally since 1825. The value to him of this timber cutting is not known, but one settler, Dugald C. McNab, estimated that between 1825 and 1836 it was between £100 and £600 annually.

Emboldened by this success, McNab, who had patented 650 acres in his own name, exclusive of the block grant, secured 200 more in 1837. His bizarre manner of acquiring the land was utterly characteristic of the man. The lot was held by Duncan McNab, an illiterate who had arrived in 1832 at his own expense and had established a farm. Five years later he exchanged the lot for one thought to have better soil and occupied by Duncan Anderson, who wanted McNab’s property for a tavern site. The chief intervened, asking the government to give the lot not to Duncan McNab but to himself, saying merely that it had been vacated by Anderson and was occupied by a squatter. He failed to add that he knew Anderson well, had taken in his sister-in-law as a housekeeper, and had had a child by her. How Duncan McNab had offended the chief is unclear, but the latter had his way and in 1840, after legal proceedings, Duncan and his family were turned out. With the help of neighbours Duncan petitioned the government for aid but, in spite of the view of Provincial Secretary Richard Alexander Tucker* that this appeared to be a genuine case of hardship, the Executive Council refused to interfere. After a continued legal battle and violence against Duncan by McNab, and despite strong public support for the former, council upheld the chief’s claim in October 1841 on the technical ground that Duncan ought to have secured a new location ticket from McNab before moving.

However vital the issue of 200 acres was to Duncan McNab, the chief’s attention between 1837 and 1841 had focused on larger matters. He tried unsuccessfully to increase his land holdings and hence his revenues. In 1837 he complained to Governor Lord Gosford [Acheson*] of the settlers’ sale of lands and departure from the township. To prevent this continuing, McNab asked to be granted a trust-deed for the full 5,000 acres allotted to him in 1823, which he had forfeited in 1836. By restoring his direct control over a large area, the grant would supposedly enable him to make over lots only to those settlers who had discharged their obligations to him. Here was another example of his dissembling methods, for those of his settlers who wished to remain were certainly not offering their improved lots for sale and their number was relatively small. In June 1838 council accepted McNab’s proposal but in October it reversed the decision. He was publicly humiliated during the rebellion of 1837–38 when some 80 militiamen from McNab refused to serve under his command in the 2nd Carleton Light Infantry because of their objections to their settlement agreements with him and because he had legally prosecuted many of them. No confusion marked council’s deliberations in 1839 when McNab asked for the 5,000 acres outright with no mention of a trust-deed. He was again turned down.

Thereafter McNab sought compensation for his reputed losses in settling the township. In February 1839 he calculated them at £5,000 (the estimated value of the 5,000 acres he had forfeited) with an additional £4,000 for his expenses over 14 years. He secured the support in Toronto of Attorney General Christopher Alexander Hagerman* and of John Strachan who, though no longer on council, now believed that McNab had received little financial return on his scheme. Council nevertheless rejected his claim for the £5,000 but felt that a fund for compensating him could be created by having the settlers buy their land. Asked in July to submit an account of his actual outlay, McNab could only produce “loose estimates,” so council fell back on his valuation of £4,000. By an order-in-council in September he was granted that amount, £1,000 of which was to be paid directly and the rest raised from the proposed sale of lands. At the same time, he was told to cease cutting timber in McNab by the end of the year except on his own 850 acres.

News that something important had happened in Toronto filtered back to the settlers, though the full contents of the order-in-council would not become known to them until 1842. By April 1840 a bitter petition had been submitted to Lieutenant Governor Sir George Arthur by 35 settlers, who denied the chief’s claim of having underwritten their settlement expenses. They further asserted that McNab was still drawing income from timber duties as well as from land rents and sales. In response to their demand for an independent inquiry into the affairs of the township, the government authorized an investigation by Francis Allan, crown lands agent for the Bathurst District, who submitted his report that November.

McNab miscalculated seriously by failing to anticipate that the inquiry would fully endorse the settlers’ position and paint a damning picture of his role. Roads were found to be in miserable condition. The one sawmill was owned by the chief, who blocked the erection of a grist-mill until late in 1840. The tax assessment for the township was less than £32. Even for an area with distinct disadvantages in the quality of its soil, this was a poor record. Most important, McNab was shown to have attempted to dominate the settlers in a thoroughly peremptory fashion. The report mentioned in particular Duncan McNab and John Campbell, a blacksmith whose tools the chief had seized and held for years after Campbell had refused to pay him rent or grant him a mortgage. In condemning McNab’s affairs, Allan did not mince words: “The system of Rent and mortgage added to an arbitrary bearing and persecuting spirit seems to have checked all enterprise and paralyzed the industry of the settlers . . . . The devotion of Scotch Highlanders to their Chief is too well known to permit it to be believed that an alienation such as has taken place between McNab and his people could have happened unless their feelings were most grossly injured.”

In the House of Assembly McNab still had friends, and it was reluctant to publish Allan’s report, which became something of a political issue. As well, in June 1841 a further petition from the settlers went unheeded by the Executive Council, which moved instead to confirm the arrangements made in 1839. Consequently an order-in-council was passed giving McNab’s settlers nine years to pay for their land and directing them to make their payments not to McNab but to the crown lands agent, thus cutting the chief off from direct access to his compensation. Then, in August, Francis Hincks*, the editor of the reform Examiner and a newly elected member of the assembly, seconded a motion by Malcolm Cameron* to have Allan’s report tabled. The motion carried against the wishes of Sir Allan Napier MacNab, Stewart Derbishire*, and 17 others. A decision by the assembly to print the report was undermined by its referral to a committee of the house, but in 1842 it was published, embarrassing the government over its past involvement and causing a further loss of support for McNab.

Allan’s progress through the township in the summer of 1840 had already roused the settlers, some of whom had sent details of their troubles to Hincks. Beginning in November 1840, Hincks began publishing in the Examiner accounts of McNab’s mishandling of the township. The chief was moved to sue Hincks for libel, with damages set at £1,000. The case was heard in April 1842 in Toronto by Jonas Jones*, who had presided at the iniquitous persecution of Duncan McNab at Perth. Hincks, whose forthcoming appointment as inspector general was evidently brought into question, was represented by Robert Baldwin, William Hume Blake*, and Adam Wilson*. Attorney General William Henry Draper*, Henry Sherwood, and John Willoughby Crawford* acted for McNab, who won the case but received only £5, a clear moral defeat. The proceedings, with all their revelations so damaging to McNab, were placed by an unremorseful Hincks before the reading public.

When the settlers in McNab learned early in 1842 of the obligatory purchase clauses in the orders-in-council of 1839 and 1841, there was further commotion. There were two more petitions, the first by settlers McNab had brought from Scotland and the second by those who had entered the township bearing their own costs. To the latter group the Executive Council merely replied, in March 1842, that as the settlers had never been promised free land they should not delay in paying the first purchase instalment for fear of seeing their lands sold. It was the last official word on that vexatious subject. In 1843, however, John Paris, who had fought McNab over the erection of a grist-mill in the township, succeeded in having him declared a public nuisance and fined by the Court of Quarter Sessions in Perth.

What was the effect of all this on McNab? Publicly his bearing remained unchanged. In August 1842 his presence at a drawing-room hosted by Lady Bagot in Kingston no doubt drew much comment. In an address to the Caledonian Society of Montreal in 1890 James Craig, an Ottawa valley lawyer, recalled talking “with some who knew the old Chief in the last days of his dying power and all unite in saying that he bore himself as of old, erect and dignified to the last. He still thought himself right and the settlers wrong. . . . And these friends . . . almost invariably said to me, ‘Don’t forget to tell how good the Chief was to the poor; how he doctored the people for nothing[,] how his house was always open to the passer on the highway, and how he never forgot his Highland home and the old, old Scottish customs; and oh dinna forget that though he was a hard man to some, yet he had a good warm Highland heart.’” Craig himself viewed McNab’s arbitrary nature as the product of his “hereditary training” and family tradition. “I can well believe . . . he meant well,” he concluded, “but the little tyrannies led to greater ones and the unlawful assertion of authority led to falsehood and cruelty to support it.” The legend of the good-hearted but misguided highland chief on the banks of the Madawaska was thus elaborated.

The public record reveals McNab to have been a thoroughly unpleasant piece of work, dangerous even to his dependents and sycophantic to those more powerful than himself. His instability of character and purpose may have reflected a drinking problem, but such an explanation lacks evidence. He was not the only chief who attempted but failed to make the transition from clan monarch of the 18th century to serious landowner of the 19th. Driven by an ambition to erect a fortune in Upper Canada, he survived only at a modest level on a remote frontier, his frequent, almost relentless, excursions to Perth, Kingston, and Toronto notwithstanding. He proved himself a consummate liar and felon who by various means, at times sophisticated and subtle, robbed both the crown and the poor. He laid almost insupportable burdens on those who crossed him, pursuing them with great vigour in the courts. Ultimately his display of greed gave the settlers the means to uncover the real nature of his settlement scheme and to break his grip on McNab Township and drive him from his last home there, on the shores of White Lake.

In 1844, when he was still trying to collect his promised compensation from the government, he left for Hamilton, where he was financially supported by Sir Allan Napier MacNab. The chief’s flair, however, never diminished. At a St Andrew’s Day celebration in Kingston in 1847, Major James Edward Alexander was struck by his appearance and commanding presence. In 1848 McNab was presented by his estranged wife, Margaret, with the estate of Rendall in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, but he remained in Hamilton until as late as September 1851. Following his return to Britain he took up with Elizabeth Marshall, the daughter of a Leeds ironmonger, with whom he had a daughter. They moved to Passy (Paris), possibly in the winter of 1854–55, and subsequently to Lannion. There McNab died in 1860, leaving behind a legend in the Ottawa valley.

Some consider Archibald McNab to be the 13th Chief (also called the 13th laird) on the basis of a pedigree of the chiefs compiled in 1768. According to the Court of the Lord Lyon, the official heraldic authority for Scotland, the correct title is 17th Chief.

AO, MU 1978; MU 2598, no.37 (hist. sketch of Archibald McNab, photocopies of clippings from Chronicle (Arnprior, Ont.), 14 Dec. 1894–1 March 1895); RG 1, C-I-1, 33, McNab to John Davidson, 6 Oct. 1841; McNab to Metcalfe, 4 March 1844; F-I-8, 37: 7; RG 22, Perth (Lanark), District Court, case files, 1837–41; clerk account book, 1816–44; ser.75, 1: 259, 285. Court of the Lord Lyon (Edinburgh), Public reg. of all arms and bearings in Scotland, 40: f.133. Ont., Ministry of Citizenship and Culture, Heritage Administration Branch (Toronto), Hist. sect. research files, Renfrew RF.5. PAC, RG 1, E3, 53: 3–7, 60, 66–68, 75, 77, 89–92, 103–14, 117–18, 123–28, 135, 135v–w, 138, 141–48, 479–81; L1, 30: 477–79; L3, 307: Mc20/20, 23; 307a: Mc20/176; 308: Mc21/10, 56, 64; 308a: Mc21/94, 121; 310: Mc22/178; 311: Mc1/32–33, 64, 71; RG 5, A1: 29944–46, 31176–77, 33170–72, 103387, 125156–83, 135733–70, 139643–46; B3, 7: 686–89; B26, 3: 556, 569; 6: 236, 1097; 8: 1258; C2, 1: 95–96; RG 68, General index, 1651–1841: 454. SRO, GD50/119–20; GD112/43–46. Univ. of Toronto, Thomas Fisher Rare Books Library, mss 5027, James Craig, “‘The McNab’ . . . address delivered at a meeting of the Caledonian Society of Montreal in 1890” (typescript, 1890). J. E. Alexander, L’Acadie; or, seven years’ explorations in British America (2v., London, 1849), 2: 2. Can., Prov. of, Legislative Assembly, App. to the journals, 1841, app. HH, nos. 1–2. Francis Hincks, Reminiscences of his public life (Montreal, 1884), 82–83. John Mactaggart, Three years in Canada: an account of the actual state of the country in 1826–7–8 . . . (2v., London, 1829), 1: 277–78.

Bytown Gazette, and Ottawa and Rideau Advertiser, 20 Dec. 1837. Chronicle & Gazette, 31 Aug. 1836; 9, 30 March, 30 April, 24 Aug. 1842; 27 April 1844. Examiner (Toronto), 11 Nov. 1840. Kingston Chronicle, 20 Dec. 1822, 17 Jan. 1823. Joseph Bouchette, The British dominions in North America; or a topographical description of the provinces of Lower and Upper Canada . . . (2v., London, 1832), 1: 83. [J. B. Burke], Burke’s genealogical and heraldic history of the landed gentry, ed. Peter Townend (18th ed., 3v., London, 1965–72), 2: 418–19, 670–71. “Calendar of state papers,” PAC Report, 1935: 182. “State papers – U.C.,” PAC Report, 1897: 168; 1898: 191–92. H. I. Cowan, British emigration to British North America: the first hundred years (rev. ed., Toronto, 1961). W. A. Gillies, In famed Breadalbane; the story of the antiquities, lands, and people of a highland district (Perth, Scot., 1938), 85–114. The last laird of MacNab: an episode in the settlement of MacNab Township, Upper Canada, ed. Alexander Fraser (Toronto, 1899). John McNab, The clan Macnab: a short sketch (Edinburgh, 1907). Marion MacRae, MacNab of Dundurn (Toronto and Vancouver, 1971). Richard Reid, “McMillan and McNab: two settlement attempts on the Ottawa River” (paper presented at Scottish conference, Univ. of Guelph, Ont., 1983). Scadding, Toronto of old (1873), 212–13. Roland Wild, MacNab: the last laird (London, 1938). M. J. F. Fraser, “Feudalism in Upper Canada, 1823–1843,” OH, 12 (1914): 142–52. G. C. Patterson, “Land settlement in Upper Canada, 1783–1840,” AO Report, 1920.

Cite This Article

Alan Cameron and Julian Gwyn, “McNAB, ARCHIBALD, 17th Chief of Clan MACNAB,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 9, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcnab_archibald_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcnab_archibald_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Alan Cameron and Julian Gwyn |

| Title of Article: | McNAB, ARCHIBALD, 17th Chief of Clan MACNAB |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | March 9, 2026 |