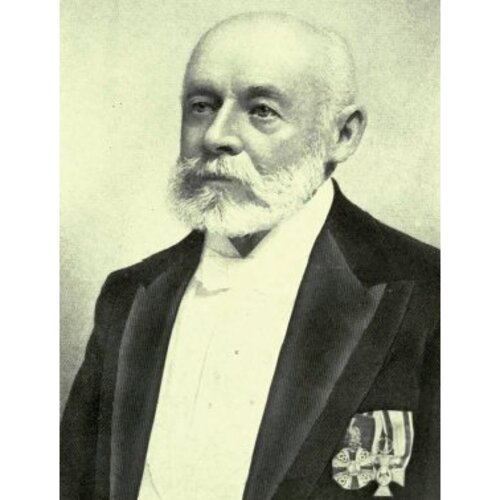

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HESPELER, WILLIAM (Wilhelm), businessman, office holder, politician, and jp; b. 29 Dec. 1830 in the Grand Duchy of Baden (Germany), second son of Johann Georg Hespeler and Anna Barbara Wick; m. first 21 Dec. 1854 Mary H. Keatchie (d. 1872) of Galt (Cambridge), Upper Canada, and they had three children, two of whom survived to adulthood; m. secondly 15 Dec. 1874 Mary Meyer (d. 1883) of Seaforth, Ont.; m. thirdly 6 April 1887 Catherine Robertson, née Keatchie (d. 1920), a sister of his first wife, in Port Arthur (Thunder Bay, Ont.); no children were born of the second or third marriages; d. 18 April 1921 in Vancouver.

William Hespeler grew up in a bourgeois household in Baden, his father a prosperous merchant and his mother related to Hungarian aristocracy. The family’s nine children, two boys and seven girls, received extensive education in German, French, and English. They were steeped in the family’s mercantile tradition and imbued with a sense of adventure which was tempered only by the inherent social conservatism of their class. The Hespelers believed not only in technological but also in political progress. Their hopes for democratic reform in Baden were dashed when the revolution of 1848 failed. The family valued service to the public and its members would frequently participate in civic and political affairs.

Through chain migration started by William’s elder brother, Jacob, most of the family eventually came to settle in Upper Canada, in the area around Berlin (Kitchener) and Waterloo. In this largely German enclave, Hespeler, who arrived in 1850, demonstrated his willingness to reach beyond his ethnic and religious background (he was Lutheran) by marrying a Canadian-born woman of Scottish-Presbyterian descent. He soon proved his business acumen as well, working initially in his brother’s milling, distilling, and general merchandising business in Preston (Cambridge). In 1854 he set up a similar business in Waterloo with George Randall. A few years later the partners built the Granite Mills and the Waterloo Distillery. By 1861 the flourishing business was producing 12,000 barrels of flour and 2,700 barrels of whiskey; it employed 15 men.

In the 1870s Hespeler’s career took a different turn. According to one account, Hespeler, a naturalized British subject, briefly served as a stretcher–bearer during the Franco-German war of 1870–71. He returned to Canada but by the spring of 1872 he had left his business in the care of an employee, Joseph Emm Seagram*, and had taken his ailing wife and two surviving children to Baden. On 2 Feb. 1872 he had been appointed special immigration agent for Germany by the Canadian government. With the help of shipping agents of the Allan Line [see Sir Hugh Allan*], he recruited new settlers, especially from the war-ravaged province of Alsace. That summer the Canadian government sent him to southern Russia, a region from which large numbers of German-speaking Mennonites wanted to immigrate. Despite considerable opposition from Russian authorities and little support from British diplomats, he arranged for several thousand Mennonites to move to Canada [see Gerhard Wiebe*].

Rewarded by the federal minister of agriculture, John Henry Pope*, with an appointment as dominion immigration agent for Manitoba and the North-West Territories (a position he would hold until 1882), the recently widowed Hespeler moved permanently to Winnipeg in 1873. Through his work in providing temporary shelter and emergency provisions as well as in directing newcomers to available lands, he had close dealings not only with the Mennonite settlements but also with the early Icelandic settlements [see Jón Bjarnason*]; he was similarly involved in organizing relief for Jewish refugees [see Benjamin Zimmerman]. Uncomfortable with the government’s laissez-faire approach to the establishment of recent arrivals, he took a paternalistic view of aid. He did not mind combining the government’s relief with his own economic self-interest as a grain merchant. He delighted in planning new settlements, such as Niverville, and in exploring agricultural innovations. Together with his son he erected what is said to have been the first grain elevator in western Canada, in 1879. He deftly explored the entrepreneurial opportunities of the frontier, acquiring rural and city plots, dealing in mortgages and loans, and acting as a middleman between the Winnipeg business community and the Mennonite settlements. From 1886 to 1905 he would serve as manager of the Manitoba Land Company. He soon became known as an expert on western Canadian development.

By the mid 1870s, remarried and at his energetic best, Hespeler proved his civic-mindedness in many ways. He was elected alderman for Winnipeg’s South Ward in 1876 and 1878, joined the board of the Winnipeg General Hospital (he would serve as its president for more than a decade, starting in 1889), and on 25 Nov. 1876 was appointed to the provisional council of Keewatin to deal with the smallpox epidemic of 1876–77. By 1876 he had also been appointed a justice of the peace. Involved in the Anglo-Saxon community of Winnipeg, he was also active among the city’s small German population. His second wife was of German origin and he himself participated in German singing and social clubs in the late 1870s and mid 1880s.

When the German government sought an honorary consul for Winnipeg and the North-West Territories in 1882, Hespeler was a natural choice. This unsalaried position allowed him to pursue his business interests and it would help him overcome personal tragedies – the death of his second wife in 1883 and that of his daughter, Georgina Hope, wife of Augustus Meredith Nanton, in 1886. As consul, he maintained his connections with the growing German community of the city. In 1888, for example, he supported the establishment of a German Lutheran congregation in Winnipeg. The following year he was instrumental in setting up a German-language newspaper, the Nordwesten. Although the consular workload became increasingly heavy in the new century, he would stay on until July 1907. In 1903 he was rewarded with the German Order of the Red Eagle for 20 years of service.

At age 69 Hespeler moved into the political arena. His reputation for thoroughness and common sense and his close association with the Mennonite community won him the rural seat of Rosenfeld in the provincial general election of 7 Dec. 1899 as an independent candidate with Conservative leanings. Once elected, however, he declared himself against the government of Conservative premier Hugh John Macdonald. On 29 March 1900 he became speaker of the Legislative Assembly, one of the earliest persons who were not born British subjects to hold this position in any legislative body in the British empire – but not the first, as has been claimed. Lacking vanity and a sense of self-importance, he left politics a few years later to make way for a younger person.

Hespeler’s business activities had laid the foundation for considerable wealth that promised a comfortable old age with his third wife, Catherine. He continued to serve on the boards of numerous financial institutions and could have lived out his final years quietly enjoying the fruits of his labour in his luxurious apartment block in Fort Rouge (Winnipeg), designed for him by noted architect John D. Atchison in 1906. World War I intervened, however. Hespeler’s German connections suddenly tainted the man and his achievements. He refused to be cowed by the nativist hostility of the period and devoted his energy to helping recent German immigrants who had lost their jobs. The city, and the rest of Canada, soon forgot him.

In his final months, after the death of his third wife in 1920, Hespeler moved to Vancouver to be with his son, Alfred. He died there and was buried in St John’s Anglican cemetery in Winnipeg, among the city’s pioneers. His obituary remembered him as a man “who was at one time so foremost in the life of the province.”

AO, RG 80-5-0-42, no.2961. Man., Legislative Library (Winnipeg), Biog. scrapbooks. Univ. of Waterloo Library, Special Coll. Dept. (Waterloo, Ont.), GA 104 (Seagram Museum fonds), sousfonds 1 (Joseph E. Seagram and Sons, Ltd fonds); sousfonds 2 (Seagram family fonds). Berliner Journal (Berlin [Kitchener, Ont.]), 1858–72. Dumfries Reformer (Galt [Cambridge, Ont.]), 27 Dec. 1854. Manitoba Free Press, 19 April 1921. Nordwesten (Winnipeg), 1889-1921. Winnipeg Tribune, 15 April 1911, 29 May 1930. Alexander Begg and W. R. Nursey, Ten years in Winnipeg: a narration of the principal events in the history of the city of Winnipeg from the year A.D. 1870 to the year A.D. 1879, inclusive (Winnipeg, 1879). George Bryce, A history of Manitoba: its resources and people (Toronto and Montreal, 1906). Mrs George Bryce, [Marion Samuel], “Historical sketch of the charitable institutions of Winnipeg,” Man., Hist. and Scientific Soc., Trans. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, reports of the Dept. of Agriculture, 1871–82. Ernst Correll, “Mennonite immigration into Manitoba: sources and documents, 1872, 1873,” Mennonite Quarterly Rev. (Goshen, Ind.), 11 (1937): 196–227, 267–83. CPG, 1901. Werner Entz, “William Hespeler, Manitoba’s first German consul,” German-Canadian yearbook (Toronto), 1 (1973): 149–52. Arthur Grenke, “The formation and early development of an urban ethnic community: a case study of the Germans in Winnipeg” (phd thesis, Univ. of Manitoba, Winnipeg, 1975). Angelika Sauer, “Ethnicity employed: William Hespeler and the Mennonites,” Journal of Mennonite Studies (Winnipeg), 18 (2000): 82–94. W. H. E. Schmalz, “The Hespeler family,” Waterloo Hist. Soc., Annual report (Kitchener), 57 (1969): 21–29. (Winnipeg), no.54 (Febrary 1899): 1–31. F. H. Schofield, The story of Manitoba (3v., Winnipeg, 1913).

Cite This Article

Angelika Sauer, “HESPELER, WILLIAM (Wilhelm),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hespeler_william_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hespeler_william_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Angelika Sauer |

| Title of Article: | HESPELER, WILLIAM (Wilhelm) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |