Source: Link

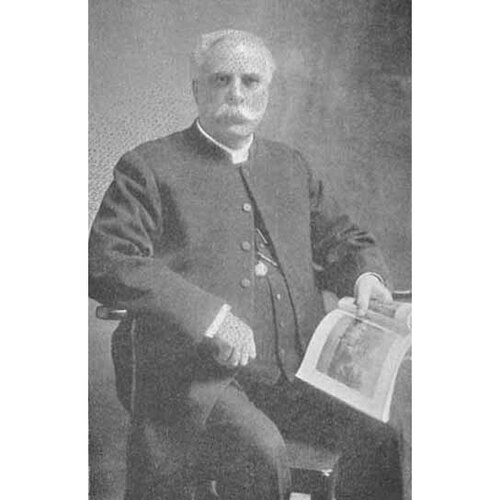

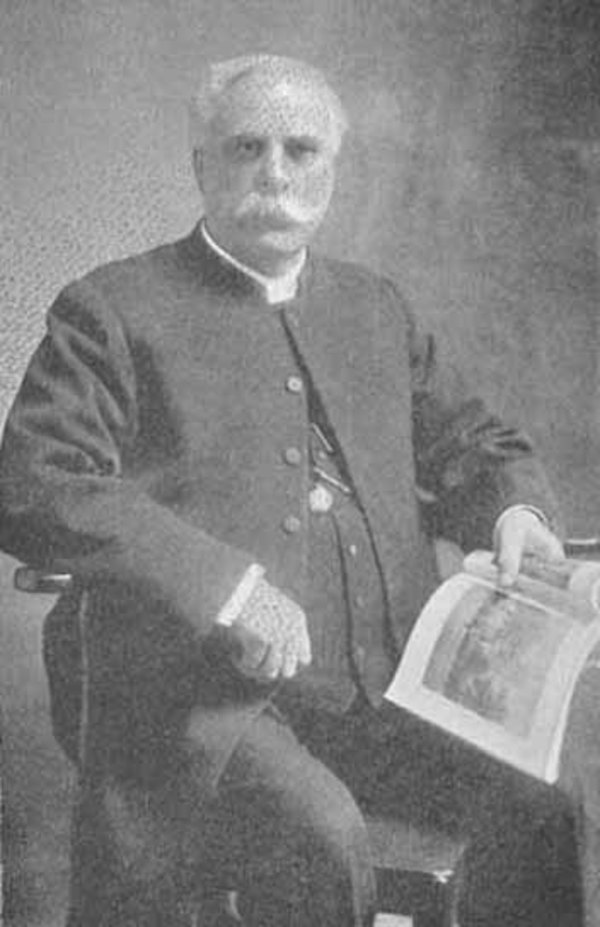

HINES, JOHN, Church of England clergyman, missionary, and author; b. 20 Feb. 1850 in Leverington, England; m. 22 June 1876 Emma Marriannie Moore (d. 1930) in Winnipeg, and they had a daughter; d. 25 Feb. 1931 in St Boniface (Winnipeg).

John Hines was born on Honey Hill Farm, in the lowlands of Cambridgeshire. His mother died when he was eight, leaving him and his younger brother; two years later their father married a widow with eight children. Of necessity, John helped farm, and had little time for school. The family’s move to the adjoining parish of Wisbech St Mary proved to be a turning point in his life: the vicar, Philip Carlyon, introduced him to and nurtured his interest in the Church of England. Following a period of upgrading his education, he was admitted to the Church Missionary Society’s Training Institution at Reading in 1873 and he remained there for ten months. Originally he was intended for Zanzibar, in Africa, but news from William Carpenter Bompas* altered the CMS’s plans for Hines. In England for his consecration as bishop of Athabasca, Bompas told the society about the devastating loss of the buffalo on the western plains of Canada and urged that any students with an agricultural background be sent to establish missions and farms among the Indians there.

Hines sailed from Liverpool on 12 May 1874 to set up, as the society put it, “a new Mission for the benefit of the Cree Indians of the great prairie.” During the voyage he met his future wife, Emma Moore, whose brother William was a clergyman in the vast western diocese of Rupert’s Land [see Robert Machray*]. Accompanied by David Stranger, a Swampy Cree from St Peter’s mission in Manitoba, Hines reached his destination, Green Lake, northwest of Prince Albert (Sask.), but found it unsuitable for farming because of its bushy and sandy soil; the two men soon moved south to White Fish (Little Whitefish) Lake.

The 1870s and 1880s were decades of major upheaval for First Nations ravaged by disease and starvation, and dispossessed of their land through treaties. Indian leaders were keenly aware of the need for their people to learn to farm and read and write so they could adapt and survive. Influential Plains Cree chief Ahtahkakoop (Star Blanket) rejoiced when he learned that an Anglican missionary with oxen and a plough had come to teach. After meeting with him in October 1874, Hines decided to settle at Sandy (Hines) Lake, a camping spot of the chief’s band that boasted fertile land, hay meadows, and timber. Hines delivered his first service on 10 Jan. 1875 to 30 worshippers in Ahtahkakoop’s house.

John McLean*, first bishop of the new diocese of Saskatchewan, ordained Hines a deacon on 9 Jan. 1876 in Prince Albert. Two weeks later McLean, Hines, and the Reverend John Alexander Mackay* of Stanley Mission made history in Hines’s one-room residence. They not only held the first CMS conference west of Winnipeg (and the first in the diocese), but they also laid the foundation of Emmanuel College, which would be opened in Prince Albert in 1879 primarily to educate native youths as teachers and pastors.

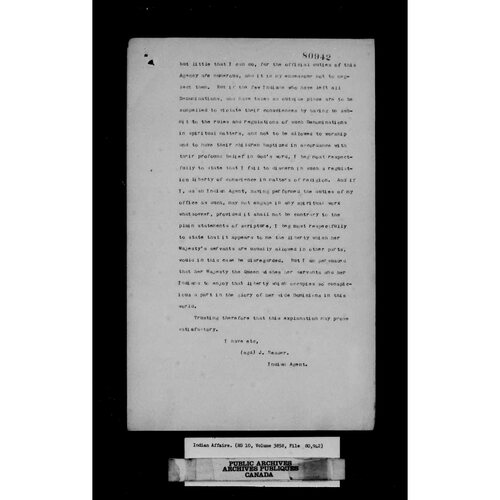

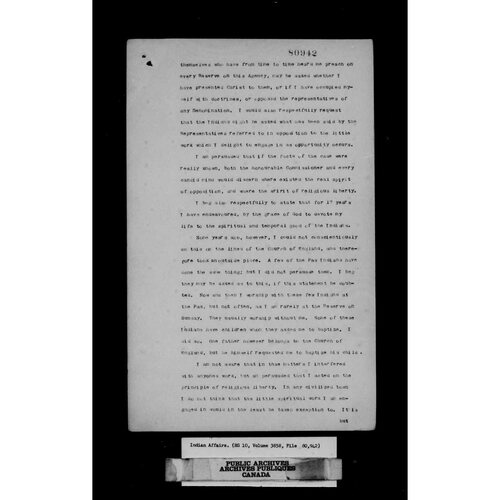

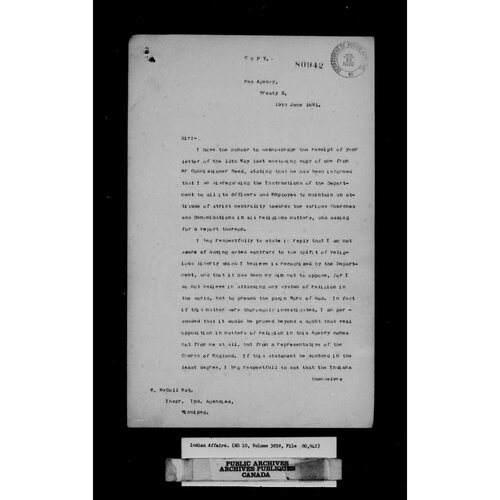

Ordained priest in 1880, Hines ably fulfilled his dual mission of agricultural training and preaching during his 14 years at Sandy Lake. The strength of his commitment is evident from an early report he made to the CMS, which ended with the motto “The Gospel & The Plough.” He demonstrated a way of life based on agriculture, teaching Ahtahkakoop’s people to sow grain and plant gardens. His efforts had some success: a number of bands in Treaty No.6, including Ahtahkakoop’s, were praised by government officials for the progress they had made, having anywhere from 20 to 120 acres under cultivation. Houses, outbuildings, a day school, and St Mark’s Church were constructed. In July 1888 Hines was transferred to The Pas (Man.), where he continued his work by erecting churches and schools, dispensing medicine, vaccinating, and taking on yet another duty as a dentist. Agricultural endeavours were stayed, however, because of the lack of suitable land. In his new post Hines had to compete with Joseph Reader* in his efforts to convert the natives. Hines served at The Pas from 1888 to 1902, during which time, in 1891, he was appointed rural dean of the Cumberland district. In 1902 he was assigned to the Prince Albert district as supervisor of Indian missions in the Saskatchewan diocese, a position he held until his retirement in 1911.

In terms of his contribution to Anglican missionary enterprise, Hines was probably most effective in helping his charges come to terms with agrarian existence, owing to his own experience as a farmer. His success, however, was certainly not his alone; the support of the Indian community, its leaders and headmen, was imperative. Although compassionate and willing to endure hardship, poor health, and loneliness to do God’s work, Hines remained a man of his times. An undercurrent of Anglo-superiority, colonialism, and paternalism was ever present in his acts and thoughts; his journal often referred to native peoples as “my Indians” and “poor things.”

He frankly chronicled his motives, activities, and attitudes in The red Indians of the plains: thirty years’ missionary experience in the Saskatchewan (London, 1915). Written “with the prayer that it may lead others, who feel called by the Spirit to serve the Master in the foreign field,” the book, like many other missionary recountings, contains descriptions of local geography, denunciations of heathenism, and reviews of Indian ways. While admitting that Indian people were “not by any means unbelievers or irreligious,” Hines felt they were a superstitious lot whose worship was based on fear, not love, and who harboured “strange customs.” Evidently, in his actions, journal, and book, he could not escape the habit of viewing all through his particular cultural lens, which resulted in a devaluation of native spirituality and a limited ability to provide a true understanding of Cree spiritual traditions and how they melded with Christianity or remained distinct. He condemned the Indians’ traditional beliefs as wrong and sinful, pressured them to destroy their medicine bundles, and ridiculed sweat-lodge ceremonies and other rites, all the while urging them towards the path of Christianity.

The Reverend John Hines spent the last years of his life in St Vital, Man. He died, blind, in St Boniface Hospital in 1931 at age 81. A plaque dedicated to his memory in 1960 and placed in St Mark’s Church, Sandy Lake, says: “The effectual, fervent prayer of a righteous man, availeth much.”

John Hines is the author of The red Indians of the plains: thirty years’ missionary experience in the Saskatchewan (London, 1915; Toronto, 1916). An electronic version of a later edition of this book (London, 1919), including the frontispiece photograph of the subject, is available at www.anglicanhistory.org/indigenous/hines. Most of Hines’s documentation of his experiences in western Canada, including reports, letters, and journals, has been preserved as part of the Church Missionary Soc. fonds (LAC, R10977-0-1; mfm. at Univ. of Sask. Library, Saskatoon). A photograph of the Hines family taken in 1882 during a visit to England is held at the Diocese of Sask. Arch. (Prince Albert, Sask.), Photograph no.210. Hines is also included in a photograph taken at the conference of the diocese of Saskchewan on 5 Aug. 1891 at St Alban’s Church, Prince Albert, N.W.T. This photo is at SAB (Saskatoon), S-B 6681.

LAC, R216-84-X (mfm. at Univ. of Sask. Library). Leader-Post (Regina), 26 Feb. 1931. Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, 26 Sept. 1960. Winnipeg Tribune, 25 Feb. 1931. Edward Ahenakew, Voices of the Plains Cree, ed. R. M. Buck (Regina, 1995). T. C. B. Boon, The Anglican Church from the Bay to the Rockies: a history of the ecclesiastical province of Rupert’s Land and its dioceses from 1820 to 1950 (Toronto, 1962). R. M. Buck, “The Mathesons of Saskatchewan diocese,” Saskatchewan Hist. (Saskatoon), 13 (1960): 41–62. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1881–1902 (reports of the Dept. of Indian Affairs, 1880–1901). Sarah Carter, Lost harvests: prairie Indian reserve farmers and government policy (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1990). Deanna Christensen, Ahtahkakoop: the epic account of a Plains Cree head chief, his people, and their struggle for survival, 1816–1896 (Shell Lake, Sask., 2000). Bruce Peel, “Historic sites: Cumberland House,” Saskatchewan Hist., 3 (1950): 68–73. T. [M.] Peikoff, “Anglican missionaries and governing the self: an encounter with aboriginal peoples in western Canada, 1820–1865” (phd thesis, Univ. of Manitoba, Winnipeg, 2000). Stewart Raby, “Indian Treaty No.5 and The Pas agency, Saskatchewan, N.W.T.,” Saskatchewan Hist., 25 (1972): 92–114.

Cite This Article

Christa Nicholat, “HINES, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hines_john_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hines_john_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Christa Nicholat |

| Title of Article: | HINES, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2014 |

| Year of revision: | 2014 |

| Access Date: | March 2, 2026 |