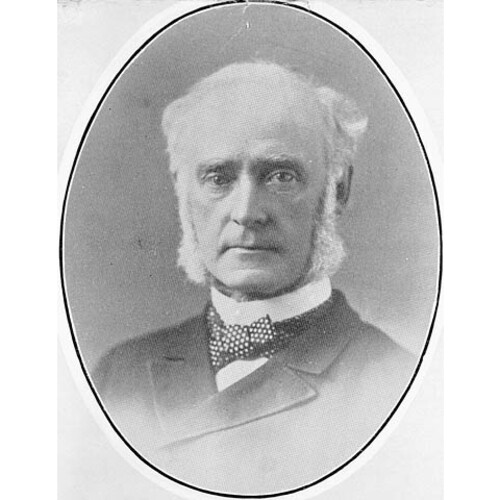

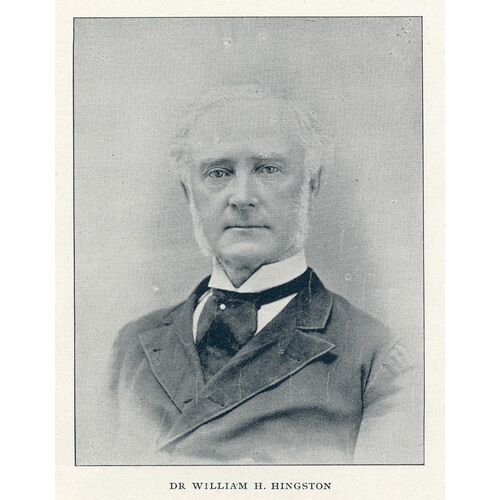

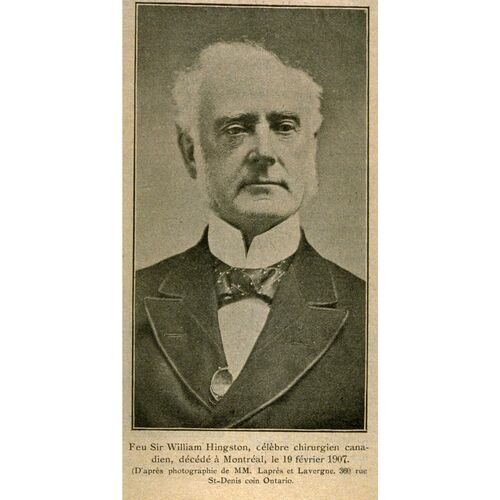

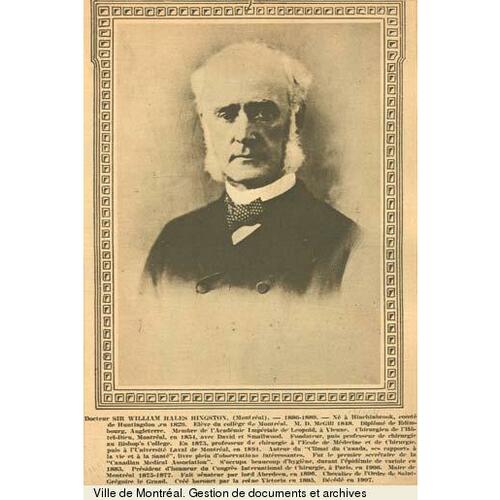

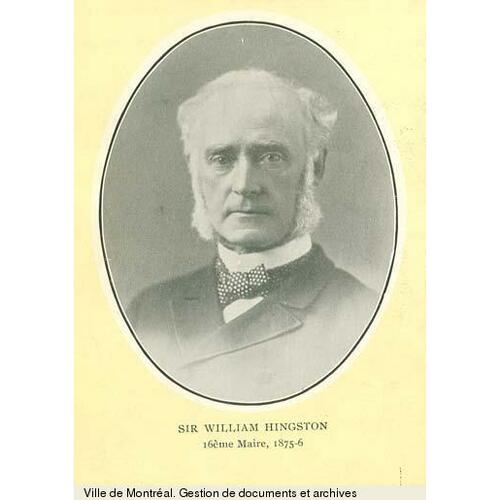

HINGSTON, Sir WILLIAM HALES, physician, surgeon, professor, author, and politician; b. 29 June 1829 in Hinchinbrook Township, Lower Canada, son of Lieutenant-Colonel Samuel James Hingston and Eleanor McGrath; m. 16 Sept. 1875 in Toronto Margaret Josephine Macdonald, daughter of Donald Alexander Macdonald* (Sandfield), lieutenant governor of Ontario, and they had five children; d. 19 Feb. 1907 in Montreal and was buried two days later in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery.

Of Irish Catholic origin, William Hales Hingston did classical studies under the Sulpicians at the Petit Séminaire de Montréal from 1843 to 1844. He then worked as a pharmacist’s apprentice between 1844 and 1847, but in 1848 he decided to study medicine at the faculty of medicine in McGill College. He graduated in 1851 and the following year he enrolled in the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh to continue his education. After receiving his diploma in surgery, he stayed in Europe and spent time in London, Dublin, Paris, Berlin, Heidelberg, and Vienna.

On his return to Montreal in 1854, Hingston opened a private medical practice, and became a surgeon and professor of clinical surgery at the Hôtel-Dieu. He would be appointed chief of surgery there in 1882. According to contemporary sources, he proved to be a diligent surgeon, efficient and blessed with “exceptional dexterity.” He performed daring operations, such as the removal in 1863 of a kidney that had been attacked by a tumour. He is believed to have been the first surgeon in Canada, if not in the world, to do such an operation, and in 1872 he would be the first in North America to undertake the excision of a tongue and lower jaw.

As professor of clinical surgery at the Hôtel-Dieu, Hingston attached a great deal of importance to the detailed examination of the cases presented to the students and encouraged them to take an active part, a rare approach in those days. In 1871 he resigned from the Hôtel-Dieu to participate in founding the Bishop’s College faculty of medicine, which was located in Montreal [see Francis Wayland Campbell]. He was appointed its dean and professor of surgery, but gave up these positions before the year ended. He resumed teaching in 1875 when he was appointed professor of surgery at the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery. President of the school in 1883 and dean in 1887, he was still professor when it merged with the medical faculty of the Montreal branch of the Université Laval in 1891, and he held the position for the rest of his life.

Hingston’s contribution to medical literature is by no means as significant, in either quantity or originality, as some authors have maintained. Apart from contributing to International Clinics (Philadelphia), between 1872 and 1880 he wrote a few articles on surgery, in particular on lithotomy, for L’Union médicale, of which he was a founder. In 1892 he also wrote for the Montreal Medical Journal, in which his “Address in surgery” appeared. A few years earlier Hingston had published The climate of Canada and its relation to life and health (Montreal, 1884), which was described by one of his contemporaries as “an elegant book, filled with interesting observations.” He also was co-author of A reference handbook of the medical sciences, published in New York in 1889.

Active within his profession and eager to foster cooperation among physicians, Hingston helped set up many medical organizations. A founding member of the Montreal Medico-Chirurgical Society in 1865 and the Canadian Medical Association in 1867, he served as president of the former and secretary of the latter. In 1886 he was elected president of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of the Province of Quebec, and he held the office until 1889. As a promoter of hospital development, he took a keen interest in the incorporation of the Women’s Hospital of Montreal in 1870 and the Samaritan Hospital for Women in 1895. He was also actively involved in putting into effect a public health policy designed to correct serious deficiencies in Montreal. In 1875 he was instrumental in creating the Citizens’ Public Health Association, under whose aegis the Public Health Magazine and Literary Review was published from 1875 to 1878. The association, which had a number of leading Montreal figures in its membership, was to serve as a movement undergirding the concrete policy that Hingston, as a politician, promoted.

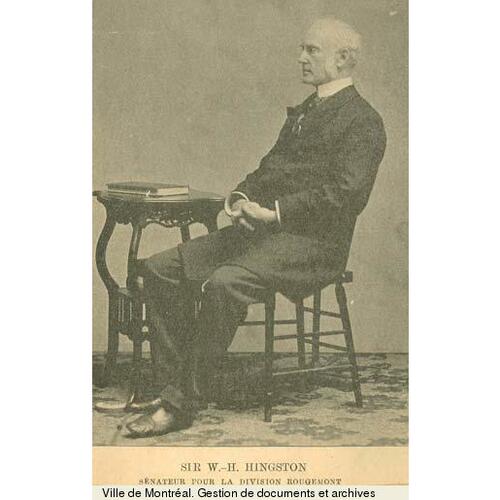

Hingston was active in municipal life. As mayor of Montreal from 1875 to 1877, he used his office to propose measures to improve the sanitary condition of the city. In 1876 he had a basic by-law passed which led to the reorganization of the municipal board of health into a permanent body and strengthened medical representation in public health administration. Hingston could now carry out a far-reaching reform of the city’s sanitation system. His work in the field of hygiene continued throughout the smallpox epidemic of 1885. Along with others, such as Dr Emmanuel-Persillier Lachapelle*, he was appointed to the central board of health set up temporarily by the government, and he was one of the physicians who recommended vaccination. As a result, his house was threatened by the rioters who opposed this prophylactic measure. Hingston took up politics again in 1895, this time as the Conservative candidate in the federal by-election of 27 December in Montreal Centre. He was defeated by James McShane* but was named to the Senate on 2 Jan. 1896.

Despite his many activities Hingston found time to pursue business interests. From 1875 to 1907 he was a director of the Montreal City and District Savings Bank, and he served from 1895 to 1907 as its president. He was president of the Montreal Street Railway Company (known prior to 1886 as the Montreal City Passenger Railway Company), and of the Montreal Safe Deposit Company.

The many honours bestowed on Hingston at the close of his busy career bear witness to the esteem in which he was held by the political and medical élites of Canada and Great Britain. On 15 July 1895 he was knighted by Queen Victoria. He became vice-president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science and honorary president of the British Medical Association. Finally, he was named honorary president of the international congress of surgery held in Paris in 1906.

AC, Montréal, État civil, Catholiques, Cimetière Notre-Dame-des-Neiges (Montréal), 21 févr. 1907. AVM, D026.16; D821.2. Academy of Medicine, The map of the history of medicine of Canada; commemorating the diamond jubilee of the Academy of Medicine, Toronto, and the confederation of Canada; painted by Charles F. Comfort, r.c.a. ([Toronto], 1967). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Édouard Desjardins, “L’histoire de la profession médicale au Québec,” L’Union médicale, 104 (1975): 131–51, 448–70. Michael Farley et al., “Les commencements de l’administration montréalaise de la santé publique (1865–1885),” HSTC Bull. (Thornhill, Ont., and Ottawa), 6 (1982): 24–46, 85–109; “La vaccination à Montréal dans la seconde moitié du 19e siècle: pratiques, obstacles et résistance,” Sciences & médecine au Québec: perspectives sociohistoriques, sous la direction de Marcel Fournier et al. (Québec, 1987), 87–127. E.-J. Kennedy, “Nécrologie: sir William Hales Hingston,” L’Union médicale, 36 (1907): 178–81. Albert Le Sage, “75e anniversaire de la fondation de ‘L’Union médicale du Canada,’ 1872–1947,” L’Union médicale, 75 (1946): 1268–69. Oscar Mercier, “Médecins et chirurgiens de l’Hôtel-Dieu,” L’Union médicale, 70 (1941): 1273–76. Recension bibliographique: les maladies infectieuses dans les périodiques médicaux québécois du XIXe siècle, André Paradis et al., compil. (Trois-Rivières, Qué., 1988). Rumilly, Hist. de Montréal, vol.3. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell).

Cite This Article

Denis Goulet and Othmar Keel, “HINGSTON, Sir WILLIAM HALES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 27, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hingston_william_hales_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hingston_william_hales_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Denis Goulet and Othmar Keel |

| Title of Article: | HINGSTON, Sir WILLIAM HALES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | February 27, 2026 |

![Sir William Hingston, 16ième Maire de Montréal [P.Q.] 1875-1876. Original title: Sir William Hingston, 16ième Maire de Montréal [P.Q.] 1875-1876.](/bioimages/w600.6169.jpg)