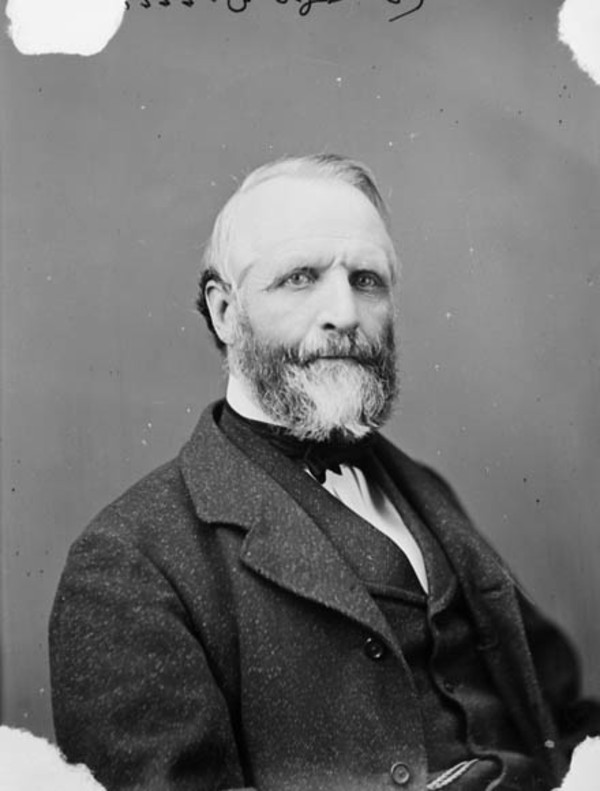

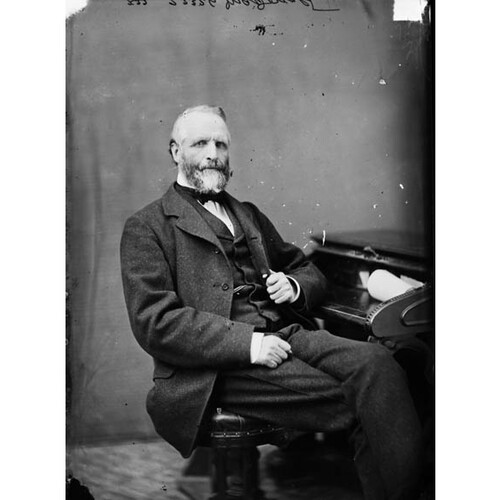

MACDONALD (Sandfield), DONALD ALEXANDER, businessman, politician, and office holder; b. 17 Feb. 1817 in St Raphaels, Upper Canada, fourth son of Alexander Macdonald (Sandfield) and Nancy Macdonald; m. first 1843 Margaret Josephine MacDonell (d. 1844); m. secondly Catherine Fraser, daughter of Alexander Fraser*, and they had at least nine children; d. 10 June 1896 in Montreal.

Donald Alexander Macdonald’s father was a Roman Catholic Highland Scot who immigrated to the upper St Lawrence valley in 1786 with the party led by the Reverend Alexander MacDonell* of Scothouse. After completing his education at Iona College in St Raphaels, Donald moved to the United States, where he became involved in 1840 in the construction of the Illinois Canal. Returning to Upper Canada, he secured a contract in the building of the Beauharnois Canal, begun in 1841. When the Irish canal workers rioted because of poor working conditions, Macdonald, though not at fault, was attacked by the mob. To escape death he jumped “into a canoe and shot the Cedar Rapids, a feat full of peril.” In Montreal he took on an aqueduct for the city’s waterworks and by 1855 he had 500 employees working on it.

In 1844, at the age of 26, Macdonald had moved with his first wife to Alexandria, a village in the back country of Glengarry County. There he established an estate, Gary Fenn, and erected a grist-mill, sawmill, general store, carding-and fulling-mill, and potashery. Because of these various entrepreneurial ventures, by 1850 he was a gentleman of considerable wealth.

Macdonald was also well connected with the Montreal business establishment and was linked to the political scene through his brother John Sandfield Macdonald*, Glengarry’s prominent member in the Legislative Assembly. Both independent reformers, they shared a strong antagonism toward the copremier, Francis Hincks*. In the early 1850s the government of Hincks and Augustin-Norbert Morin* became involved in several education bills, to which Donald was opposed. A university bill, passed in April 1853, modified the secular University of Toronto [see Robert Baldwin*], created University College as the teaching body, left the university as the examining and degree-granting agency, and made provision for denominational colleges to affiliate as teaching units and to receive possible financial support. Under pressure from Irish and French Catholics, legislation was passed in 1853 to extend provisions for separate schools in Upper Canada. Although D. A. Macdonald was a Scottish Catholic he opposed the promotion of segregated religious school systems. In Glengarry he was not alone in this sentiment – many Scottish settlers were quite happy to live as they had, without separate schools. However, Bishop Patrick Phelan* of the diocese of Kingston, which included Glengarry, and the Irish-dominated executive of the diocese were aggressive in the fight to further separate schools. Their determination only stiffened the opposition of the Scottish Catholics of Glengarry. As reeve of Kenyon Township, Macdonald, never one to shy away from a contentious issue, took the lead in the battle against Phelan. Under his direction the counties council of Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry unanimously passed a resolution in 1853 which condemned the University Act, and Macdonald publicly denounced Phelan and the Irish for attempting to promote sectarian education.

To undermine the influence of the Macdonald brothers, in 1854 Phelan sent to Alexandria as priest Father “Spanish” John McLachlan, who, although a Scot, had sided with the bishop over the separate school issue. Glengarry then had 61 common schools and no separate ones, and the teacher in Alexandria was a Protestant. On Easter Sunday 1854 McLachlan read from the pulpit an episcopal letter exhorting Catholics to establish their own schools and preached on the subject. An incensed Donald Macdonald left his pew at the end of the service and harangued his village folk from the church doorway on the folly of segregated education. The next Sunday McLachlan preached against the absent “petty miller” and untalented “devil’s agent” who had “sprung from nothing . . . like mushrooms on a dung hill.” Macdonald responded to this personal assault by charging the priest with defamation of character but he lost his suit.

In 1856 Macdonald became warden of Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry. The following year, when John Sandfield decided to run for the assembly in Cornwall, Donald ran successfully as a Reformer in Glengarry. He secured re-election in 1861 and 1863. In 1859, at the Grit Reform convention in Toronto [see George Brown*], he gave a keynote address condemning a dissolution of the union of Upper and Lower Canada as unacceptable to the eastern, Montreal-centred counties. Five years later he joined his brother in opposing the Quebec resolutions for confederation, believing that dissolution would be ruinous to the interests of the St Lawrence region. After confederation he was elected to the House of Commons in 1867, 1872, and 1874. John Sandfield’s political pact in 1867 with Sir John A. Macdonald, which enabled him to become the first premier of Ontario, had distanced the brothers from each other. Donald preferred to be a leading Grit in Ottawa. Some of his colleagues, however, were suspicious of him because of his brother’s alliance with John A. The death of John Sandfield in 1872 removed this anomaly. In 1873 Donald became postmaster general in the cabinet of Alexander Mackenzie, who thought little of his potential as a minister but who could not ignore him as the senior Liberal in eastern Ontario. Macdonald left the cabinet in 1875 to become the lieutenant governor of Ontario, an appointment caused in part by the need to open a place in the cabinet for Edward Blake*. He remained in that vice-regal post until 1880.

Macdonald’s long concern with the three counties had also been demonstrated over railways. The Alexandria businessman had realized the advantages of building a railway through northern Glengarry and from the 1850s tried to have such a line constructed. He lobbied, unsuccessfully, to have the Grand Trunk serve the area. In 1854, however, Donald and his brothers Ranald Sandfield and John Sandfield received a contract from it to build the section from Farran Point in Stormont to Montreal.

Donald nevertheless remained a bitter critic of Hincks and the Grand Trunk. His own critics suggested that the contract was awarded to him and his brothers to mollify the family’s hostile attitude towards the company but it did not stop Donald from finding fault with the Grand Trunk. In particular he was infuriated that so much of the construction had been given to British contractors. Speaking in April 1855, he emphasized the company’s mismanagement of funds and the poor quality of the railway except for the portion “let to us poor Canadian sub-contractors.”

In 1871 Alexandria still did not have a railway connection, and so Macdonald determined to build a line himself. He headed a group of 14 investors, 7 from the Glengarry area, who obtained parliamentary authorization to form the Montreal and City of Ottawa Junction Railway. The line would run from near Coteau-Landing on the Grand Trunk through Alexandria to Ottawa. Then, in 1872, Macdonald and a group of 6 investors formed the Coteau and Province Line Railway and Bridge Company to extend this line southward into New York State, providing access to the American markets for Ottawa valley lumber and other products.

The depression of 1873 temporarily stopped Macdonald’s railway ambitions. In 1879 the two companies amalgamated to form the Canada Atlantic Railway Company. Financial support for this project was provided by the Ottawa lumber baron John Rudolphus Booth*. Macdonald became president, but his association with the new company was short-lived. He resigned from the presidency in 1881 and by 1882 was not even a director.

In 1882, retired from public office, Macdonald sought election to his old seat but he was defeated. He had had a long career in politics, which, it could be argued, had much to do with his being the brother of John Sandfield. During the general election of 1872 a local analyst, Donald McMillan, provided a more persuasive explanation in a letter to Conservative party manager Alexander Campbell. He argued that the Sandfield family had controlled the area politically for 32 years. A second reason was Donald’s “great wealth, having as he said 1600 notes out in [Glengarry County], a lever no doubt used freely this time.” McMillan also considered the possibility of Macdonald’s using jobs on railway construction as a form of patronage at election time. His electoral defeat in 1882 seems to be linked to the still uncompleted railway. The farmers and businessmen of the area had looked forward to its coming. To facilitate construction they had supported the plan of Kenyon and Lochiel townships to provide the railway with a $50,000 grant. Even though the project was not completed, the money was spent, leaving the citizens to pay for the grant through their taxes. There were accusations, before and after the 1879 merger, of dishonesty on the part of the railway companies. The outrage was so intense that in December 1881 Macdonald was shouted down by spectators at a meeting at the Kenyon town hall.

A minor scandal which had occurred during his term as lieutenant governor may also have influenced the electoral returns in 1882. Macdonald had led an official tour from Toronto to Winnipeg and the cost (in excess of $5,500) was much criticized in the provincial legislature. The trip, labelled the “Corkscrew Brigade” because of an expenditure on corkscrews, resulted in a committee of inquiry and Macdonald’s offer to return $350 to cover his personal expenses.

Macdonald never returned to political life after 1882. He retired to his estate in Alexandria to look after his many business interests. He died in Montreal in 1896. Tragically, in a period of 15 months in 1863–65, he had lost his wife and four of their children to diphtheria. A surviving daughter, Margaret Josephine, married noted surgeon and mayor of Montreal William Hales Hingston*.

Paul W. White wishes to express his gratitude to Eugene Macdonald of Alexandria, Ont., a grandson of the subject, who granted an interview in May 1987.

AO, RG 22, ser.194, reg. K (1894–97): 348–55. MTRL, Robert Baldwin papers. NA, MG 24, B30; B40; MG 26, A. Can., Prov. of, Legislative Assembly, Journals; Parl., Confederation debates. Ont., Legislature, Journals, 1867–72. D. B. Read, The lieutenant-governors of Upper Canada and Ontario, 1792–1899 (Toronto, 1900). Globe, 1844–72, 11 June 1896. True Witness and Catholic Chronicle (Montreal), 27 Oct., 10 Nov., 8 Dec. 1854. Witness and Canadian Homestead (Montreal), 10 June 1896. Canadian biog. dict. J. M. S. Careless, Brown of “The Globe” (2v., Toronto, 1959–63; repr. 1972), 1. Charles Clarke, Sixty years in Upper Canada, with autobiographical recollections (Toronto, 1908). J. G. Harkness, Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry; a history, 1784–1945 (Oshawa, Ont., 1946). B. W. Hodgins, “John Sandfield Macdonald,” The pre-confederation premiers: Ontario government leaders, 1841–1867, ed. J. M. S. Careless (Toronto, 1980), 246–314; John Sandfield Macdonald, 1812–1872 (Toronto, 1971); “The political career of John Sandfield Macdonald to the fall of his administration in March, 1864: a study in Canadian politics” (phd thesis, Duke Univ., Durham, N.C., 1964). R. [C.] MacGillivray and Ewan Ross, A history of Glengarry (Belleville, Ont., 1979). Swainson, “Personnel of politics.”

Cite This Article

Bruce W. Hodgins and Paul W. White, “MACDONALD (Sandfield), DONALD ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_donald_alexander_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_donald_alexander_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Bruce W. Hodgins and Paul W. White |

| Title of Article: | MACDONALD (Sandfield), DONALD ALEXANDER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |