Source: Link

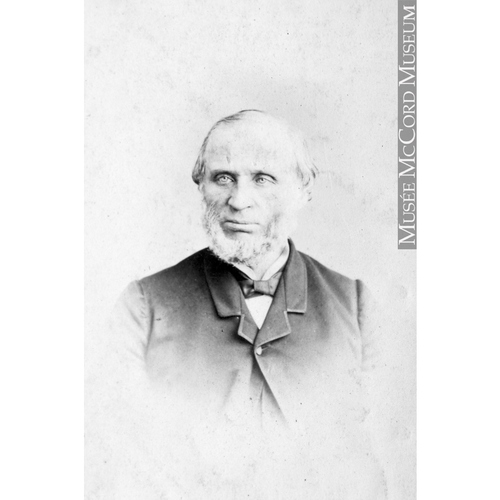

HUDON, VICTOR, businessman; b. 31 Aug. 1812 in Rivière-Ouelle, Lower Canada, son of Alexandre Hudon and Julie Chapais (Chapet); m. first 20 July 1835, in Montreal, Marie Godard, and they had three daughters and six sons; m. there secondly 31 July 1886 Philomène Godard; d. 28 March 1897 in Montreal.

Prominent as a merchant, banker, and industrialist whose factories hired hundreds of workers, Victor Hudon was a celebrated member of Quebec’s regional bourgeoisie. Yet although he was a businessman whose affairs were far from negligible, he was not in the same league as such powerful members of Canada’s national bourgeoisie as fellow Montrealers George Stephen* or Donald Alexander Smith*. By the last decades of the 19th century control over the Canadian economy was falling into fewer and fewer hands and capitalists such as Hudon were being pushed aside by those with greater resources. Hudon’s experience was similar to that of other members of the regional bourgeoisie, many of whom were franco-phones, and his career illustrates the marginal role of the French-speaking bourgeoisie in the Quebec economy by the turn of the 20th century.

Hudon began his business career as clerk in a Quebec City firm in 1830. In 1832 he moved to Montreal to fill a similar position in the commercial house of Jean-Baptiste Casavant on Rue Saint-Paul Later that year Casavant sent Hudon to manage his branch store at Saint-Césaire, a small town southeast of Montreal. During the rebellion, major battles were fought at nearby Saint-Denis and Saint-Charles-sur-Richelieu in 1837 [see Wolfred Nelson*; Thomas Storrow Brown*], and in later years Hudon claimed to have been at both engagements, although he was vague as to the precise role he played. The year 1837 was also significant – in Hudon’s business career. He left the employ of Casavant to strike out on his own as a merchant in partnership with N. C. Chaffers of Saint-Césaire. The business appears to have been successful and branch stores were soon opened at Saint-Pie and Saint-Dominique.

In 1842, ready to expand his business activities, Hudon moved back to Montreal, where he formed a dry-goods and grocery firm with his cousin Ephrem Hudon. The partnership continued until 1857 when Victor Hudon left to set up his own firm for the import and export of a wide variety of goods. He was a frequent traveller to Europe, but seems to have specialized in business with Cuba, importing sugar and molasses in exchange for exports of Canadian lumber. Given his interest in international trade, he was sensitive about the slightest suggestion of increased tariffs, and he made his attitude perfectly clear in an 1870 letter to Sir George-Étienne Cartier*, in which he described tariffs as nothing more than an incentive to smuggling.

During these years of commercial prominence in Montreal, Hudon’s affairs no doubt benefited from his involvement with the Banque Jacques-Cartier. Like other French-speaking businessmen of the time he was willing to aid in the establishment of financial institutions that might provide the credit not always made available to them by the large English-run institutions in Montreal, notably the Bank of Montreal. In 1861 Hudon was among the group of francophones, mostly merchants, who formed the Banque Jacques-Cartier and who served on its first board of directors. This bank, which publicly claimed to serve “the French Canadian trade,” was of great help to merchants such as Hudon, and in catering to this specific clientele it expanded rapidly during the 1860s and early 1870s. The depression of the mid 1870s, and revelations of dishonest and unconventional banking practices on the part of the bank’s cashier (general manager), forced the Jacques-Cartier to suspend operations in June 1875. Rumours circulated that the directors had been aware of the activities of their cashier, and when the bank reopened for business later in the year Hudon was among the directors purged in a thorough overhauling of its management.

By 1875 Hudon had won considerable acclaim as an industrialist, preserving as a consequence a solid reputation in the community despite the Jacques-Cartier fiasco. In 1873 he had established the V. Hudon Cotton Mills Company, Hochelaga (Montreal), with an authorized capital of $200,000. In February 1874 the authorized capital was increased to $600,000 and the factory began production with great fanfare. A banquet featuring prominent business, political, and church figures of Montreal, including Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau, was held to mark the event. Hudon, whose stated intention was to hire Quebeckers who had emigrated to work in American mills, was proclaimed a national hero. The Gazette reported that the workers were “French-Canadians who have been trained in American factories.” Hudon was also seen as an example of the vitality of French Canadian entrepreneurship. This national pride was expressed by L’Opinion publique: “It is possible to note that this business is completely French Canadian. We are so often accused of apathy, even incompetence in industrial matters, that [now] we surely have the right to show off our achievements and to say: This is our handiwork!” At the time of opening, the mill could produce about 12,000 yards of cotton a day and provided employment for some 250 workers; by the early 1880s it had 800 workers.

From the beginning the company proved an unequivocal financial success. A 10 per cent dividend was paid in 1878, followed by a 333 per cent stock bonus in 1880 and 10 per cent dividends on the enlarged capital in both 1881 and 1882. Another stock bonus, this one doubling the company’s capital, was awarded to the shareholders in 1883, but by this time Hudon was no longer associated with the mill that bore his name. He had called upon outside capital in 1881–82 to finance an expansion of the mill, bringing the production of cotton goods up from 42 million yards in 1877 to 15 million yards in 1882, and this dependence upon larger financial interests was ultimately his undoing. In February 1882 a new board of directors led by Andrew Frederick Gault* and David Morrice was elected by the shareholders and Hudon was deposed as president.

Hudon did not mope about his defeat for long. Only one month later he was reported to be establishing an “opposition cotton mill” in Hochelaga with the support of an industrial bonus from that municipality. This new firm, the Compagnie de Filature Ste-Anne, with an authorized capital of $300,000, had a very brief corporate existence. Hudon lost control some time in 1883, and in 1885, when the company merged with the V. Hudon Cotton Mills Company to form the Hochelaga Cotton Manufacturing Company, he was no longer a member of the board. Gault and Morrice, the controlling interests in the new company, went on to combine 14 major Canadian cotton mills into two firms: Dominion Cotton Mills Company (Limited) in 1890 and Canadian Colored Cotton Mills Company in 1892. Concentration in the textile industry was one of the first steps in the late-19th-century cartelization of the Canadian economy and Victor Hudon was one of the first victims.

During the last decade of his life, Hudon, already in his seventies, returned to the wholesale grocery trade as a partner in the Montreal firm of Hudon, Hébert et Compagnie. He focused an impressive letter-writing campaign on leading Conservative politicians in an effort to obtain an appointment to the Senate. Hudon had various motives for seeking this post. On the one hand he saw it as a means of gaining funds for a railway project that he was trying to launch. He doubted whether he could secure subsidies for the project from the federal government and the Senate seat was perceived as an alternative form of federal aid. As he wrote to cabinet minister Mackenzie Bowell* in October 1891, “A place as Senator . . . will give me the necessary influence to get people to take shares in our Railway.” More frequently, however, Hudon gave as a reason the services rendered during his career. He referred to his industrial successes, but placed greater emphasis upon his long years of loyalty to the Conservative party. In the same letter to Bowell he wrote, “I have always been a conservative and have never changed my mind in politics. I have disbursed large sums especially given to Sir John A. [Macdonald] for the province of Ontario, besides having subscribed for several counties in Quebec . . . to which I have given $40,000. I have never received one Dollar from the Government for all that.” Referring to an unsuccessful attempt to win a seat in the 1872 federal election, he added: “I have run in Hochelaga against Mr [Louis Beaubien*] but I had only three weeks ahead of me to organise my committees. . . . With all this to my credit I have not been named a Senator.” In a subsequent letter to Bowell, Hudon insisted, “I am not begging, but claim what is thoroughly due me.” Hudon never did obtain his Senate seat, and the one patronage position he did hold, a place on the Montreal Harbour Commission from the 1850s, slipped out of his grasp upon the election of Wilfrid Laurier* and the Liberals in 1896.

At the time of his death in 1897 Hudon was a rather pathetic figure, a man who had taken considerable risks in business and who had helped pioneer the industrial development of Montreal in the second half of the 19th century, only to be pushed aside by men with greater wealth.

NA, MG 26, A, Hudon to Macdonald, 25 May 1883, 1 Nov. 1887; C, Hudon to Abbott, 5, 20 Oct., 20 Dec. 1891; MG 27, 1, D4, 2:680. Can., Royal commission on the textile industry, Report (Ottawa, 1938); Statutes, 1900, c.98. Canadian Manufacturer (Toronto), 31 March 1882. Ont., Statutes, 1894, c.63. Que., Statutes, 1875, c.66; 1885, c.62. Gazette (Montreal), 16 Feb. 1875, 29 March 1897. Monetary Times, 1 Jan. 1875, 31 March 1882, 2 April 1897. Montreal Daily Star, 29 March 1897. L’Opinion publique, 26 févr. 1874. La Presse, 31 mars 1898. Canadian album (Cochrane and Hopkins), vol.4. Canadian biog. dict.

Cite This Article

R. E. Rudin, “HUDON, VICTOR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 8, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hudon_victor_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hudon_victor_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | R. E. Rudin |

| Title of Article: | HUDON, VICTOR |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | March 8, 2026 |