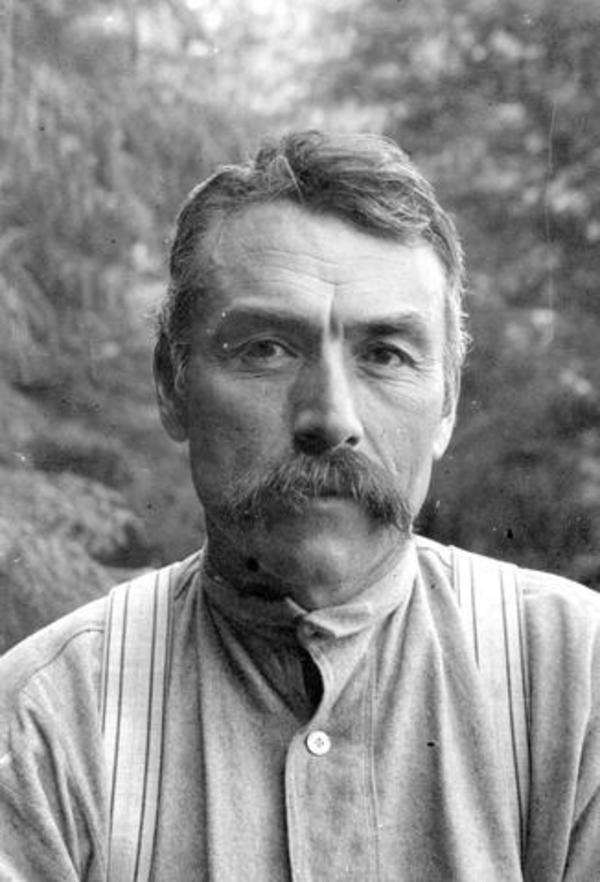

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

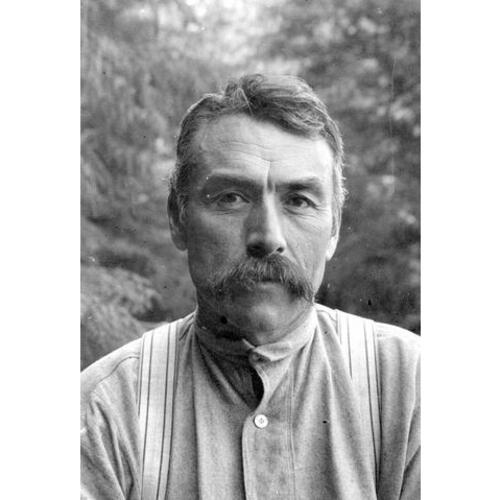

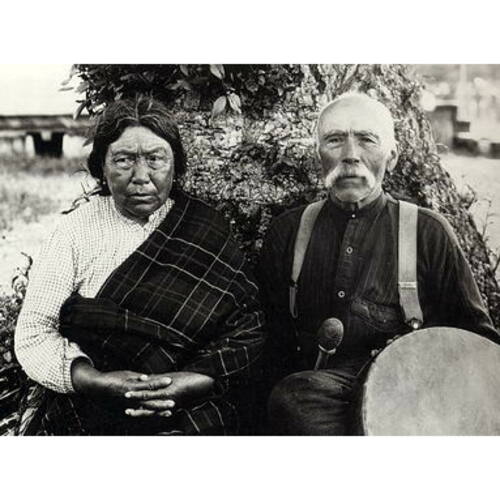

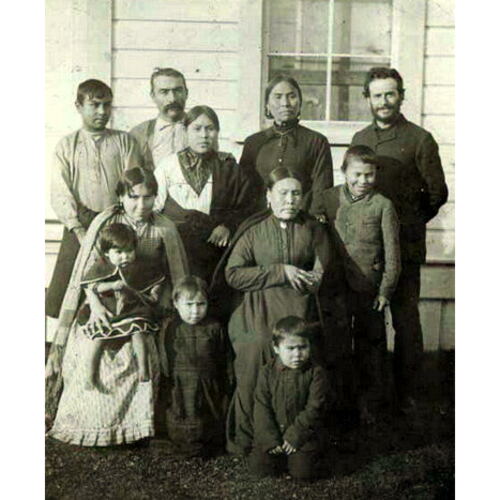

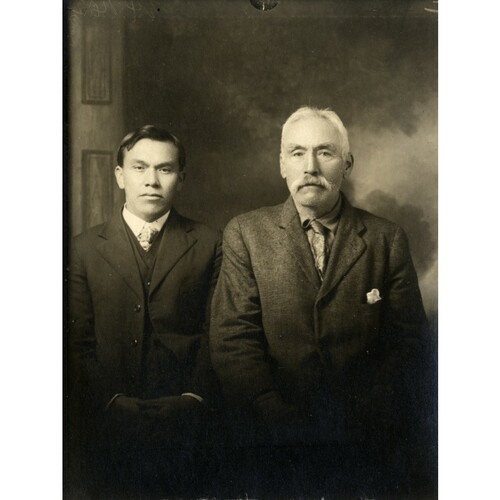

HUNT, George (also named Xawe, ’Maxwalagalis, K’ixitasu, and Nołq’ołala), HBC employee, interpreter, guide, and ethnographic fieldworker and consultant; b. 14 Feb. 1854 in Fort Rupert or Tsaxis (near Port Hardy, B.C.), son of Robert Hunt of Dorsetshire, England, and Mary Ebbitts (Ebbets), also known as Anein and Anisalaga, a Tongass (Taant’a Kwáan) Tlingit from the southernmost tip of what is now Alaska; m. first 1872 Lucy Homiskanis, also known as T’łaliłi’lakw (d. 1908), and they had four sons and three daughters who survived to adulthood; m. secondly c. 1912 Francine T’łat’łaławidzamga, also known as Tsukwani; no children were born of the second marriage; d. 5 Sept. 1933 in Fort Rupert.

A key figure in the history of the ethnography of the north Pacific coast, George Hunt was raised among the Kwakiutl. (This name was generally applied to all native speakers of the Kwak’wala language during the 19th and 20th centuries, but it has been replaced by Kwakwaka’wakw. The former name is still used to denote those from the Fort Rupert community.) In boyhood, George was known as Xawe, meaning loon, which may be a translation of his Tlingit name. At his first and second marriages he received the names ‘Maxwalagalis and K’ixitasu respectively. Both of his wives were Kwakiutl, Lucy from the native community at Fort Rupert, and Francine from Blunden Harbour. In his capacity as an official of the Fort Rupert winter dances he would be called Nołq’ołala.

Although Hunt would travel frequently, mostly along the central coast of British Columbia, he resided all or nearly all of his life at Fort Rupert, where his father was a Hudson’s Bay Company employee and, from 1871 to 1882, the postmaster. He initially followed in his father’s footsteps, and started to work for the HBC just before he turned 10. The company records note that at age 17, he was “well spoken of as steady and useful” (probably the words of chief factor James Allan Grahame*). He was already entrusted with extended buying expeditions to native communities, including voyages on which he captained the company’s sloop Mystery and its crew of four. He also began to act as an interpreter and guide for missionaries and travelling colonial officials, types of employment which he undertook more often as the fur trade declined.

In 1879, on his second tour of the coast with the province’s superintendent of Indian affairs, Israel Wood Powell*, Hunt, at Powell’s behest, made his first foray into the acquisition of ethnographic artefacts. This event marked the beginning of a new career, one he would pursue for the rest of his life, as a buyer, fieldworker, and consultant for collectors, museum officials, and ethnographers. In addition to Powell, these men included Johan Adrian Jacobsen, Franz Boas*, George Gustave Heye, Edward Sheriff Curtis, Samuel Alfred Barrett, Pliny Earle Goddard, Edward Sapir, and Charles Frederic Newcombe*. Hunt became one of the principal collectors of ethnographic objects from the region, procuring masks, clothing, hunting and fishing equipment, carpentry tools, dishes for feasts, and everyday eating implements. He was partly or wholly responsible for most of the collections of Kwakiutl material culture in the world’s museums that were assembled during his lifetime. The two largest, each numbering over 1,000 objects, are at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Milwaukee Public Museum in Wisconsin. In addition, the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Que., the Ethnological Museum in Berlin, the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle, and the National Museum of Natural History (Smithsonian Institution) and the National Museum of the American Indian, both in Washington, D.C., hold artefacts found by Hunt.

During the years 1911 to 1914 Hunt assisted photographer and ethnographer Edward Sheriff Curtis with his pictures of the Kwakiutl. He was also an indispensable member of the crew assembled for the filming of Curtis’s motion picture, In the land of the head hunters (1914), which starred Kwakiutl actors. A restored version entitled In the land of the war canoes would be released in 1973. Among his other roles, Hunt served as set carpenter, stage manager, interpreter, special-effects man, props and costumes supplier, and chief cultural consultant.

Hunt’s most important ethnographic employment was with German-born American anthropologist Franz Boas. Their first documented meeting was in 1888. They were in communication from 1891 until Hunt’s death, and they worked together through more than four decades, except in the period 1912 to 1915. At first their collaboration focused on the acquisition and documentation of ethnographic items. The climax of this phase was Hunt’s involvement from 1897 to 1904 with the extensive research and gathering activities of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition [see James Alexander Teit*], a project sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History.

In the mid 1890s Boas also began paying Hunt to provide linguistic, ethnographic, and folkloric information about the Kwakiutl, primarily in the form of Kwak’wala-language texts written in an alphabet of Boas’s devising that they continued to refine throughout their collaboration. During his lifetime, Hunt produced as many as 10,000 manuscript pages in Kwak’wala with English interlineations. He covers a wide range of topics, from myths and family histories to carpentry and cooking methods. Boas published 11 volumes of Hunt’s texts, most of them under his own name; for various reasons several volumes of material remain unpublished.

Because of Boas’s dominant position in the history of North American anthropology, this so-called five-foot shelf of Kwak’wala texts has possessed an iconic status, regarded as both positive and negative, even while the texts themselves have been poorly understood. Hunt’s texts are essentially his half of an epistolary ethnography that consists of a copious exchange of information, comments, and instructions. Communication between the two was punctuated only intermittently by face-to-face meetings with Boas. The encounters usually took place during Boas’s visits to British Columbia, although Hunt twice travelled east to work with Boas: he was in Chicago for six months in 1893, when Boas trained him in the Kwak’wala writing system and he helped to organize a Kwakiutl display for the Columbian exposition, and in New York for two months in 1903. Although Boas presented Hunt’s texts as the product of a Kwakiutl mentality, embodying “the culture as it appears to the Indian himself,” the texts were shaped as much by Boas’s research agenda as by Hunt’s own perspective and interests. And Hunt, of course, was not Kwakiutl by birth, upbringing, or self-identification. Although he was fluent in Kwak’wala, his spelling suggests that he had a Tlingit accent and the texts contain occasional grammatical errors. He did enter deeply into the cultural and social life of the Kwakiutl, most significantly through his marriage to Lucy and through his sons, who fell heir to the seats of several high-ranking Kwakiutl chiefs.

In fact, missionaries and government authorities saw Hunt as too deeply enmeshed in Kwakiutl life, and they frequently warned him about his involvement in the banned potlatch and winter dances. In 1900 Hunt was arrested and tried for participating in a “dance against the Law.” His lawyer managed to obtain an acquittal – with publications provided by Boas to support his argument – on the grounds that Hunt’s presence at the event had been purely in the interests of scientific observation.

This incident points to complex and even conflicting perspectives manifest in Hunt’s writings: on the one hand those of a resident outsider, employed to conduct research by some of the most eminent scholars of his day, and on the other of a man who, by choice, had nearly assimilated into the Kwakiutl. For example, regarding shamanism, he wrote, “Sometimes I believe, and sometimes I do not believe.” A key aspect of his texts is his concern with procedural detail rather than with cultural significance, as if to the end of his life he remained focused on the rules he had had to learn to participate in Kwakiutl life.

Hunt’s outsider status, the complexity of his Kwak’wala, and a writing system that is difficult for most readers are among the issues that have led some to criticize the texts as a whole. In fact, Hunt’s Kwak’wala embodies elements of a formal oratorical style used by high-ranking chiefs of the period. Boas affirmed the authenticity of some of its uncommon features. Regarding the content of the texts, he noted that, when he had checked Hunt’s information with other natives, he “invariably found that [Hunt’s] statements are correct.” Hunt himself often spoke of obtaining information from a broad selection of Kwakiutl elders. Overall, his labours in artefact collecting and ethnographic writing must be seen as an enduring achievement. They document the Kwakiutl of his era in more depth and detail and from more angles than can be found in any other single ethnographic enterprise on the north Pacific coast – and perhaps in North America.

Texts by George Hunt that were published under the name of anthropologist Franz Boas include: “The Kwakiutl of Vancouver Island,” American Museum of Natural Hist., Memoir (New York), [8] (1909), pt.ii: 301–522; Kwakiutl tales (New York, 1910) ; Columbia University contributions to anthropology (37v., New York, 1913–56), 3 (Contributions to the ethnology of the Kwakiutl, 1925), 10 (The religion of the Kwakiutl Indians, 2v., 1930), 26 (Kwakiutl tales, new series, 2v., 1935–43); “Ethnology of the Kwakiutl, based on data collected by George Hunt,” ed. Franz Boas, Bureau of American Ethnology, Annual report (Washington), 35 (1913/14): 43–1481; “Bella Bella tales,” American Folk-Lore Soc., Memoirs (New York), 25 (1932). Under his own name, Hunt published “The rival chiefs: a Kwakiutl story,” rev. Edward Sapir, in Boas anniversary volume: anthropological papers written in honor of Franz Boas …, ed. N. M. Butler et al. (New York, 1906), 108–36. The two articles that appeared under both names are “Kwakiutl texts,” American Museum of Natural Hist., Memoirs, 5 (1902–5), pts.i, ii, iii, and “Kwakiutl texts – second series,” American Museum of Natural Hist., Memoirs, 14 (1906), pt.i: 2–269.

The most important collection of Hunt’s unpublished manuscripts is held by the American Philosophical Soc. (Philadelphia, Pa) in mss 497.3.B63c, Kwakiutl, 28, 31, W1a.3, W1a.15, W1a.19; Nootka, W2a.5. Hunt’s extensive correspondence with Boas, which covered a period of over 40 years, can be found in the Franz Boas professional papers held by the same organization in mss.B.B61p. The American Museum of Natural Hist. (New York) also holds some of Hunt’s correspondence as well as accession records for artefacts he collected. Photographs of over 1,000 items Hunt acquired for the museum can be found in its “Anthropology collections database”: https://anthro.amnh.org/collections (consulted 28 July 2016).

AM, HBCA, Biog. sheets, Robert Hunt. Judith Berman, “‘The culture as it appears to the Indian himself’: Boas, George Hunt, and the methods of ethnography,” in History of anthropology (12v., Madison, Wis., 1983–2010), 8 (Volksgeist as method and ethic: essays on Boasian ethnography and the German anthropological tradition, ed. G. W. Stocking, 1996), 215–56; “George Hunt and the Kwak’wala texts,” Anthropological Linguistics (Bloomington, Ind.), 36 (1994): 482–514. Franz Boas, Kwakiutl ethnography, ed. Helen Codere (Chicago, 1966). Jeanne Cannizzo, “George Hunt and the invention of Kwakiutl culture,” Canadian Rev. of Sociology and Anthropology (Toronto), 20 (1983): 44–58. Douglas Cole, Captured heritage: the scramble for northwest coast artifacts (Vancouver and Toronto, 1985). E. S. Curtis, The North American Indian, being a series of volumes picturing and describing the Indians of the United States and Alaska, ed. F. W. Hodge (20v., New York, 1907–30), 10. The ethnography of Franz Boas, trans. Hedy Parker, comp. R. P. Rohner (Chicago, 1969). “George Hunt, collector of Indian specimens,” in Chiefly feasts: the enduring Kwakiutl potlatch, ed. Aldona Jonaitis (exhibition catalogue, American Museum of Natural Hist., Seattle and New York, 1991). B. M. Gough, Gunboat frontier: British maritime authority and northwest coast Indians, 1846–1890 (Vancouver, 1984). Bill Holm and G. I. Quimby, Edward S. Curtis in the land of the war canoes: a pioneer cinematographer in the Pacific northwest (Vancouver, 1980). Milwaukee Public Museum, Publications in primitive art (4v., Milwaukee, Wis., 1964–72), 2 (Masks of the northwest coast, ed. Robert Ritzenthaler and L. A. Parsons, intro. S. [A.] Barrett, 1966).

Cite This Article

Judith Berman, “HUNT, GEORGE (Xawe, ’Maxwalagalis, Q’exitaso, Nołq’ołala),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hunt_george_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hunt_george_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Judith Berman |

| Title of Article: | HUNT, GEORGE (Xawe, ’Maxwalagalis, Q’exitaso, Nołq’ołala) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2017 |

| Year of revision: | 2017 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |