Source: Link

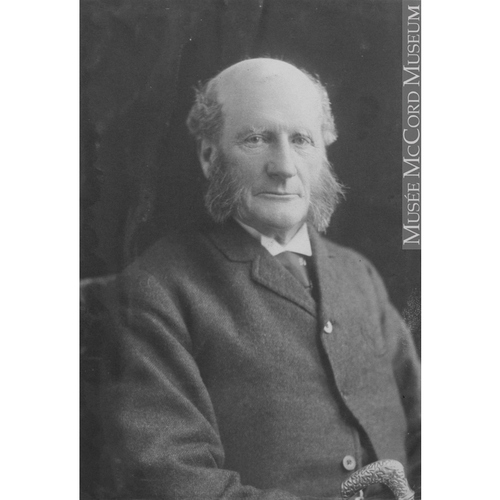

IRVINE, GEORGE, lawyer, teacher, politician, and judge; b. 16 Nov. 1826 at Quebec, son of John George Irvine, a merchant, and Ann Bell; m. there 19 Aug. 1856 Annie Routh LeMesurier, daughter of merchant Henry LeMesurier*, and they had at least eight children; d. 24 Feb. 1897 at Quebec.

The grandson of Mathew Bell* and James Irvine*, George Irvine belonged to two important families who were influential in the political and economic life of Lower Canada early in the 19th century. Nothing is known about his childhood and youth, except that he did his classical studies at Quebec with the Reverend Francis James Lundy. He was called to the bar on 7 Jan. 1848 and practised first in partnership with Charles Gates Holt, and later with Edward H. Pemberton. Eventually he became a specialist in commercial law and taught it at Morrin College, founded in 1862. His family and professional contacts were assets that he turned to good advantage. He quickly rose to the top of his profession and was one of the lawyers most sought after by lumber merchants and financiers. Made a qc on 28 March 1868, he was bâtonnier (president) of the Quebec bar in 1872–73 and in 1884–85. On 23 June 1875 Bishop’s College made him its chancellor (which he remained until 11 April 1878), and the following day it granted him a dcl honoris causa.

In the spring of 1863 Irvine had been elected the Liberal-Conservative member for Mégantic. It is hard to know what led him into politics, especially since he seldom spoke in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada and was frequently not even in attendance. He made no notable contribution to the debates in 1865 on confederation and voted only once on the amendments. It was his fame as a jurist and the fact that he came from the English-speaking minority, rather than his record of political service, that led Premier Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau* to appoint him solicitor general in the first cabinet of the province of Quebec in July 1867.

Irvine proved highly knowledgeable in constitutional law. Within the cabinet and the assembly, he followed closely the negotiations on the division between Quebec and Ontario of the Province of Canada’s debt. He sought to ensure that the constitutional provisions were put into effect and looked after the interests of both the Quebec region and his own riding, as well as the organization of the system of justice. He also attended to railway matters as a member of the committee on railways from 1867 to 1876. With his cultivated, cool, and methodical mind, he was a formidable debater, whose eloquence derived from the coherence, precision, and clarity of his arguments. An Anglican, and in sympathy with the broadmindedness of the Catholic clergy of Quebec City, he did not take kindly to the rise of the ultramontanist wing within the Conservative party. After the 1871 provincial election, he opposed the establishment of a Jesuit university in Montreal and of an altered system of registering births, marriages, and deaths, two projects sponsored by Bishop Louis-François Laflèche. Irvine was deeply involved in provincial politics and the English-speaking minority considered him their voice within the government following the departure of Christopher Dunkin* on 25 Oct. 1871; thus he did not stand as a candidate in the 1872 federal election.

Chauveau’s resignation in 1873 led to a cabinet shuffle. Gédéon Ouimet* replaced him as premier and Irvine became attorney general. In this capacity he gave his support to contractor Thomas McGreevy the following January when the contract for the construction of the North Shore Railway was let. In the summer of 1874 the Tanneries scandal [see Louis Archambeault*] put him in the political limelight. The sale of a piece of land to a speculator with the approval of the cabinet, from which, however, some information had been withheld, came as a profound shock to Irvine. His resignation on 30 July, followed by that of two other ministers, Joseph Gibb Robertson and John Jones Ross*, brought about the fall of the Ouimet cabinet and created lasting enmity between Irvine and Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau, the solicitor general of Quebec. Irvine sat from then on as an independent Conservative until the provincial election of 1875, when he was elected as the Liberal member for Mégantic.

In December 1875, during a debate on the construction of the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental, Irvine took up the cause of the south shore railways. Not wanting to see him sit as a Liberal, Premier Charles-Eugène Boucher* de Boucherville appointed him commissioner of the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental, with the task of examining the accounts and claims of contractors receiving government subsidies. Irvine gave up his seat on 28 Jan. 1876, but spent more time practising his profession than overseeing contractors. As counsel for the shareholders of the bankrupt Levis and Kennebec Railway, in 1877 he undertook a series of court actions against entrepreneur Louis-Adélard Senécal*, thereby worsening his relations with Chapleau, who had become provincial secretary. At the time of the coup d’état effected by Lieutenant Governor Luc Letellier* de Saint-Just, Irvine rallied to the Liberals Re-elected in Mégantic on 1 May 1878, he carried on his battle against the Senécal–Chapleau duo in the Legislative Assembly. Appearing before the committee on public accounts in 1880, he attacked Senécal and Clément-Arthur Dansereau*, who had engineered the Tanneries affair. In May 1881 the party in power tried to implicate Irvine in a fraudulent scheme connected with the sale of the Levis and Kennebec Railway, but the assembly exonerated him. In October and November, along with Honoré Mercier, Irvine defended L’Électeur of Quebec and Wilfrid Laurier*, who were being sued by Senécal following the publication on 20 April 1881 of an article entitled “La caverne des 40 voleurs.” In the spring of 1882 Irvine unsuccessfully opposed the sale of the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental to a syndicate set up by Senécal, arguing that Sir Hugh Allan* had put in a higher bid.

When Premier Chapleau left the provincial scene in the summer of 1882, Irvine supported a coalition between Mercier and Joseph-Alfred Mousseau*, that is, between the moderates of both parties. But the coalition collapsed. Moderate and ultramontanist Conservatives agreed to a truce and rallied around John Jones Ross, who formed a transitional government. Mercier, as leader of the opposition, stopped at nothing, and in the spring of 1884 gave free rein to his aspirations for provincial autonomy. Irvine, who saw the dominion parliament as the supreme authority and thought that the provinces possessed only delegated powers, found himself in an uncomfortable position in the Liberal party. He was unable to see eye to eye either with Mercier’s supporters or with the radical Liberals of the Montreal newspaper La Patrie. He used his political influence to obtain an appointment to the bench. On 7 June 1884 he was named judge in the Court of Vice-Admiralty for the district of Quebec, and on 2 Oct. 1891 judge in admiralty of the Exchequer Court for the same district. He pursued his brilliant career as a lawyer in other courts, and even appeared before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

On relinquishing his position as the member for Mégantic on 6 June 1884, George Irvine had been given the “rather rare distinction of being appointed a judge by his political opponents.” His colleagues in the assembly recognized him as the specialist in “questions of constitutional law” and gave him “the homage that is rendered to just and honest men.” On the occasion of his departure, Mercier summed up his whole career in public life: “The house is losing one of its leading lights; the opposition, one of its towers of strength; politics[,] one of its ornaments,” but “the country’s judiciary will be the beneficiary.” Irvine continued to live up to this testimony until his death on 24 Feb. 1897.

Bishop’s Univ., Arch. and Special Coll. (Lennoxville, Que.), Minutes of the business meeting of convocation, 212, 216–17, 232. Cathedral of the Holy Trinity (Quebec), Reg. of baptisms, marriages, and burials, 31 Jan. 1827, 19 Aug. 1856. St Matthew’s Anglican Church (Quebec), Reg. of baptisms, marriages, and burials, 26 Feb. 1897. Que., Legislative Assembly, Journals, 1867–84. Le Journal de Québec, 9, 23 juin 1863. Quebec Daily Mercury, 24 Feb. 1897. F.-J. Audet, “Commissions d’avocats de la province de Québec, 1765 à 1849,” BRH, 39 (1933): 594. “Bâtonniers du barreau de Québec,” BRH, 12 (1906): 342. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth). J. Desjardins, Guide parl., 40, 174, 193. A. R. Kelley, “The Quebec Diocesan Archives: a description of the collection of historical records of the Church of England in the diocese of Quebec,” ANQ Rapport, 1946–47: 199, 202, 277, 280. Lucien Lemieux, “Juges de la Cour de vice-amirauté de Québec,” BRH, 12: 308. P.-G. Roy, Les avocats de la région de Québec, 225; Les juges de la prov. de Québec, 272. RPQ. L.-P. Audet, Le système scolaire de la province de Québec (6v., Québec, 1950–56), 4: 179–80. Réal Bélanger, Wilfrid Laurier; quand la politique devient passion (Québec et Montréal, 1986). Cornell, Alignment of political groups. M. Hamelin, Premières années du parlementarisme québécois. Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vols. 1–4; Mercier et son temps, 1: 163–64, 177, 218, 224.

Cite This Article

Jean Hamelin and Michel Paquin, “IRVINE, GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 8, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/irvine_george_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/irvine_george_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean Hamelin and Michel Paquin |

| Title of Article: | IRVINE, GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | February 8, 2026 |