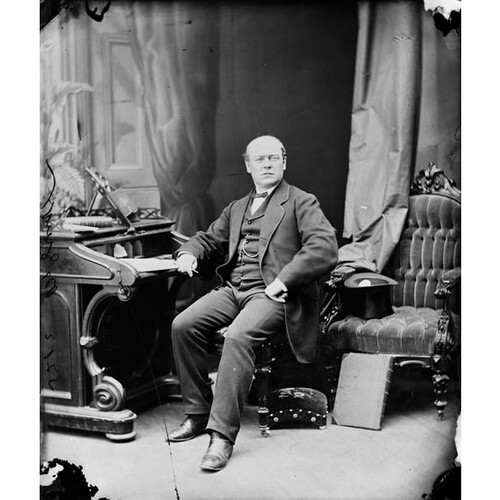

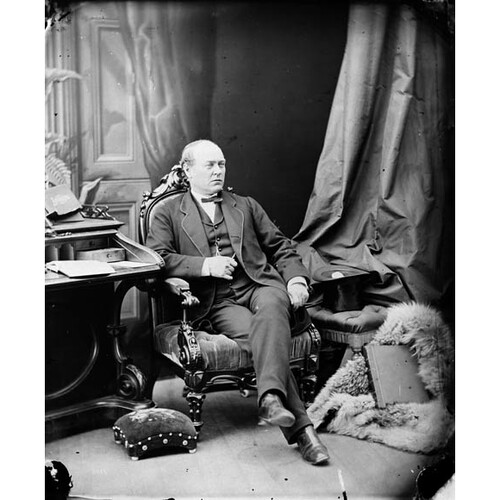

McGREEVY, THOMAS, businessman and politician; b. 29 July 1825 at Quebec, son of Robert McGreevy, a blacksmith, and Rose Smith; m. there first 13 July 1857 Mary Anne Rourke; m. there secondly 4 Feb. 1861 Bridget Caroline Nowlan; m. there thirdly 30 Jan. 1867 Mary Georgina Woolsey, and they had two sons and two daughters; d. 2 Jan. 1897 in his native city.

Thomas McGreevy was the son of an Irish craftsman who had emigrated to Quebec. In 1842 he was apprenticed to Joseph Archer Sr, a carpenter and general contractor, who passed on to him the handicraft traditions of Devon, England, which had such a strong impact on the building trades in Canada. When his apprenticeship was finished, McGreevy became a carpenter in the construction industry and soon was known for his energy. In 1850 he listed himself as a contractor and builder. On his own or sometimes with a partner, he carried out repairs and erected private dwellings and buildings of various kinds. In 1854 he put up the presbytery of St Patrick’s Church on Rue Saint-Stanislas from plans drawn by architect Goodlatte Richardson Browne. The construction of this stately edifice was tangible evidence of McGreevy’s competence and efficiency as a contractor. On 15 Dec. 1856 he signed a contract with the Department of Public Works for a custom-house. This huge structure, designed by Toronto architect William Thomas*, had a basement, ground floor, and second storey. With its Doric portico, and the 30-foot dome added in 1910 after a fire, the building was for a long time one of the most beautiful in the city of Quebec. Completed at a cost of $227,000, it was opened on 1 Aug. 1860.

This contract raised McGreevy to the rank of a major contractor. It established his reputation and led him to take an interest in public life. Leaving the faubourg Saint-Roch, he settled in Upper Town. In the fall of 1857 he ran for election as a municipal councillor in Montcalm ward, where most of the Irish in the city lived. His victory was contested but was later confirmed by the Superior Court, and he took the oath of office on 12 Oct. 1858. After two consecutive terms he stood down in 1864. His appointment to the finance committee in 1862 and to the special committee to amend the charter of the city the following year was an indication of his growing influence at City Hall, despite his rather irregular attendance at council and committee meetings. His position as a councillor gave him an entrée to the Quebec community and led to a close friendship with Hector-Louis Langevin*, the member for Dorchester in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada since 1858 and mayor of Quebec from 1858 to 1861.

Thenceforth McGreevy had access to the upper echelons of the Liberal-Conservative party. There had been a hint of this connection when he was awarded the contract to build the custom-house, and proof of it came with the contract to erect the Parliament Buildings. On 7 May 1859 the Department of Public Works announced a competition for the design of buildings in Ottawa to house parliament and the various government departments [see Thomas Fuller]. A ceiling of $300,000 was set for the construction of the main building, and $240,000 for the secondary buildings. Several months later the government awarded the contract to McGreevy, even though his tender, unlike that of a competitor for a like amount, had no attached schedule of costs which would make it possible to evaluate and monitor the work. McGreevy then managed to have a new contract for the secondary buildings awarded to Jones, Haycock and Company, but kept for himself the construction of the main building. This project, begun on 20 Dec. 1859, went badly from the start. The excavation proceeded slowly because of rock outcroppings. The plans proved incomplete, providing for neither a heating nor a ventilation system. Costs skyrocketed. As a result, there were rumours, later confirmed by the report of a royal commission in 1863, that department officials had themselves devised the schedule which McGreevy had failed to attach, using estimates submitted by his competitors, and that, when they drew up the second contract, they neglected to include certain price lists as well as clauses restricting extras and ruling out the contractor’s right to compensation if he exceeded the approved limits. The royal commission brought to light the waste of government funds and administrative omissions in the Department of Public Works, but it avoided clarifying the relations between the leading figures of the Liberal-Conservative party, its election fund, and the contractors. It merely recommended that new contracts be offered to the contractors. In retrospect, a closer examination of the documents shows that McGreevy and other Quebec contractors enjoyed the patronage of two assembly members, Joseph-Édouard Cauchon* and Langevin, and did not hesitate to have anyone who opposed their plans pushed aside, as witness the dismissal of architect Charles Baillairgé* from the Department of Public Works in 1865. That year the government was able to move into its new premises, which, by the time they were completed in 1878, would have cost some $4,000,000.

The scandal over the Parliament Buildings led to the resignation in June 1861 of the chief commissioner of public works, John Rose*. It brought about the dismissal of the deputy commissioner, Samuel Keefer*, and tarnished the reputation of the Liberal-Conservative party. It substantiated rumours that the party in power was using the Department of Public Works as a source of funds and patronage. McGreevy, on the other hand, benefited from the affair, becoming a wealthy and powerful man within the party. In 1866 he was living in Quebec at 7 Rue d’Auteuil. The city directory lists him as a contractor, vice-president of the Union Bank of Lower Canada (1862–94), commissioner for the turnpike roads on the north shore (1863–81), and vice-president of the Asile de Sainte-Brigitte, a shelter for indigent Irish. At this point, on the strength of promises given by the leaders of the Liberal-Conservative party, he took a new tack in his career, becoming a financier and a politician. On 29 Nov. 1866 he signed a deed, witnessed by notary Philippe Huot, transferring his equipment and the uncompleted part of his 1863 contract for the Parliament Buildings to his brother Robert (his partner since at least 1857) for about $25,000. This deed may have been accompanied by a verbal agreement for an out of court division of the profits on the contract. It now looks as if the brothers agreed to split the work. Thomas was to be the political broker and the financier, negotiating contracts and raising funds; Robert, the contractor, was to fulfil the contracts; they were to share the profits. The agreement was thus modelled on the situation at the time the construction of the Parliament Buildings had begun, when Robert had been manager of the project and Thomas the political go-between.

In 1867 McGreevy had a sumptuous Italianate residence built for himself at 69 Rue d’Auteuil. Designed by architect Thomas Fuller, the house had a foyer decorated with sculpture, a staircase with banisters embellished by carved leaves, and a ballroom on the second floor. The façade was of yellow sandstone, identical to that used in the construction of the Parliament Buildings. In 1895 the residence was valued at $20,000. McGreevy’s move to it marked the beginning of his new career.

Throughout 1867 McGreevy was involved, along with Langevin and Cauchon, two of the most influential local Conservative leaders, in the various negotiations in the region around Quebec that accompanied the first elections to the House of Commons and the establishment of federal and provincial institutions. He busied himself with recruiting candidates and financing the campaigns. On 24 August he himself was returned by acclamation in Quebec West, thereby becoming one of the 52 members from the province of Quebec who supported Sir John A. Macdonald, the prime minister. In November he was appointed to the Legislative Council of the province of Quebec to represent Stadacona division, a seat he held until 1874. Public speaking did not come easily to McGreevy, and he did not make his maiden speech in the commons until March 1880. He was, and intended to remain, an éminence grise. A pragmatist, he did not care about the political stripe of men or parties as long as it served his personal ambitions. His activities suggest that he wanted to build an empire for himself grounded in the highly competitive but promising field of rail and water transportation. He had two assets: the Union Bank of Lower Canada, which could advance him the funds he needed, and his position within the Liberal-Conservative party.

McGreevy’s political responsibilities gave him access to the information he needed, and he made good use of it. In the Legislative Council, he was a member of the committee on contingent accounts and the special committee to inquire and report on the classes of acts for the incorporation of private companies. In the commons, he sat on the railway, canal, and telegraph committee, as well as the committee on banking and commerce. On 5 July 1870 his brother Robert obtained the contract to build section 18 of the Intercolonial Railway. The partnership was proceeding according to the 1866 agreement. Thomas had devised the contract and raised the funds, and he was keeping the books; Robert carried out the terms. According to both men, it resulted in a net loss of $170,430.35, giving rise to a lawsuit before the Exchequer Court of Canada in 1888. The McGreevy brothers were awarded $65,000 in compensation.

There was hardly a regional transportation firm that McGreevy did not have a hand in. He was a director of the Quebec Marine Insurance Company in 1867, the St Lawrence Tow Boat Company in 1867–68 and again from 1870 to 1874, and the Quebec Harbour Commission from 1871 to 1874; president of the St Lawrence Steam Navigation Company from 1874 to 1891; and a director of the North Shore Railway Company from 1871 to 1876. The railway project, which was so promising, was especially close to his heart. But, as a shrewd businessman, McGreevy speculated in land and diversified his investments. He acquired 4,951 acres in Watford Township in March 1867 and he held mortgages on lots in Nicolet and properties at Quebec. He invested in mining and manufacturing, and owned 1,530 shares, valued at $22,000, in the English and Canadian Mining Company, of which he was a director from 1869 to 1871. In 1869 he gambled $7,500 on a sulphuric acid plant which was built at Lauzon on land belonging to the St Lawrence Tow Boat Company. That year he sold 30,000 pine sawlogs, valued at $20,000, to Valentine Cooke, a merchant, and in 1870 he bought 80,000 from William Gerrard Ross, who owned a sawmill at Saint-Nicolas.

The Canadian Pacific Railway scandal, uncovered by Lucius Seth Huntington* in the spring of 1873, marked the beginning of some difficult years. McGreevy was one of the people whom company president Sir Hugh Allan* was believed to have won over to his cause by bribes and blocks of shares. This affair besmirched the Liberal-Conservative party, which suffered defeat in the federal elections of 1874. McGreevy himself won a seat at Ottawa; however, with the abolition of the double mandate he gave up his position on the Legislative Council on 21 Jan. 1874 in order to pursue a career in the House of Commons. It was a logical choice. Langevin, who was at the centre of McGreevy’s network of political influence, was busy on the federal scene. Along with the Pacific Scandal, the severe depression of 1873–78 added to McGreevy’s worries. Shortly before resigning from the Legislative Council, he had obtained, through George Irvine, then the attorney general of the province of Quebec, and Langevin, the contract to build the North Shore Railway. He went to England to raise capital but returned empty-handed, and he tried, in vain, to fulfil the conditions of his contract by means of private capital and subsidies from the province and the city of Quebec. The provincial government had no choice but to intervene. In the fall of 1875 it amalgamated the Montreal Northern Colonization Railway and the North Shore Railway into the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway and took over direct control of its construction through a chief engineer and a board of commissioners. McGreevy was awarded the contract to build the eastern section for $4,732,387 under strict but not iron-clad conditions. The work progressed with difficulty, interrupted by strikes, rivalry between Quebec and Montreal over the route, political manipulation, and disagreements between the contractors and the chief engineer about extras and the quality of materials. On 15 June 1880 the government took possession of the eastern section, which had cost much more than originally estimated. The affair was similar to that of the parliament buildings: the Quebec Conservative party was believed to have used to its own advantage, through the contractors’ financing of party activities and support of its newspapers, sums of money earmarked for the construction of the railway. Two major problems were still unsettled: an unpaid bill to McGreevy for extras, amounting to at least $1,000,000, which was referred to an arbitration committee, and the use to be made of the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway.

In October 1878, just as the railway was nearing completion, the Conservatives were returned to power in Ottawa. The following year Macdonald reappointed Langevin minister of public works, and at the same time made him the political successor to Sir George-Étienne Cartier*. Langevin felt he needed a loyal, discreet, and efficient man at his side to distribute appointments, favours, and election funds, so as to strengthen his authority and maintain party unity. At that time Canadian political parties were organizations dominated by a core of prominent public figures; their continuity and vitality were maintained by senators, members of parliament, and newspaper editors. In the absence of dues-paying members, the parties relied on rebates from public contracts and various forms of patronage to finance their activities and to strengthen the loyalty of their supporters. Under this system, the party treasurer, who was responsible for collecting funds from the wealthy and distributing them as the political leaders directed, held a key position; Langevin decided to give this post to McGreevy. It was a role in keeping with his image as an éminence grise and with his personal ambitions: it opened the door to the mysterious world of power, where politicians and businessmen reconciled their interests. Naturally, whenever he was in Ottawa McGreevy made his home at Langevin’s residence.

The sale of the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway in 1882 was the first major transaction in which McGreevy participated in a double capacity: as party treasurer, he acted for Langevin and the Quebec premier, Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau; as businessman, for Louis-Adélard Senécal*. The CPR bought the western section of the railway. The North Shore Railway financial syndicate, a group set up by McGreevy, purchased the eastern section at the beginning of March 1882, with the connivance of Senécal, who as superintendent of the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway was both vendor and purchaser. The syndicate had assets of $1,000,000; McGreevy underwrote $100,000 in shares, and Senécal $160,000. The transaction was carried out through political manœuvring marked by keen rivalry between the CPR, the Grand Trunk, and Allan, who already owned the Dominion Line. The syndicate resold its newly acquired property to the Grand Trunk, which in turn sold it to the CPR.

Never at a loss for ideas, McGreevy himself fabricated another source of electoral funds for Langeevin. In 1880 he had been reappointed to the Quebec Harbour Commission, and in 1882 he conspired with a group of Quebec contractors – Michael and Nicholas Knight (Karrol) Connolly, Owen Eugene Murphy, and Patrick Joseph Larkin – to defraud the public treasury. He put his influence, connections, and privileged information at the service of Larkin, Connolly and Company when dredging contracts were put out for public tender by the federal government. In return, the partners brought his brother Robert into their company and were to pay him a commission of up to 30 per cent on certain contracts. From 1882 to 1890 the two had a rich source of funds: the firm obtained contracts at Quebec and Esquimalt, B.C., worth more than $3,000,000. Robert is believed to have received $188,000 in commissions, and Thomas $114,000 for political use and $58,000 in personal compensation. Senécal died in 1887 and three years later McGreevy became president of the Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company, which Senécal had also served in this capacity. McGreevy was now at the height of his power.

McGreevy’s strength depended on a modicum of unity within the federal Conservative party and on that body’s predominance in both Canada and Quebec. The Riel affair in 1885 [see Louis Riel*], which brought Liberal Honoré Mercier to power in Quebec in 1887, as well as Chapleau’s meteoric rise within the Canadian Conservative party at Langevin’s expense, and a fight to the finish in Quebec between ultramontanes and moderate Conservatives, radically changed the political situation. No longer able to reconcile his interests with those of the party, McGreevy committed a series of blunders. Eager to pocket $1,500,000 in extras on the construction of the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway, he aligned himself more closely with Premier Mercier, and increasingly funded the activities of the Quebec Liberals at the provincial level. But federally he supported Langevin in his struggle with Chapleau and the Montreal group, much to the detriment of the scheming Joseph-Israël Tarte*. Disappointed that his brother Robert, who was drawing substantial sums from the Esquimalt contract, refused to repay a number of debts to him, totalling by his estimate some $400,000, McGreevy brought an action against him in the Superior Court on 27 June 1889. This step may have been an indication of dissension creeping into the coalition that was draining the resources of the Department of Public Works. McGreevy claimed that his opposition to interference by some of the coalition in the management of the Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company, of which he was president and Murphy a director, caused a falling out with his brother and Murphy. By the beginning of 1890 McGreevy was a marked man The political rivalries were too keen, and the interests at stake proved too great, for there to be any possibility of arbitration between the parties, as witness the failure of pressures brought to bear on Macdonald to get rid of the Langevin–McGreevy duo, or at least McGreevy himself.

Events moved rapidly. Tarte took it upon himself to bring down the colossus. In the 18 April 1890 issue of his newspaper Le Canadien he published a rumour that Mercier was getting ready to pay McGreevy $800,000 in settlement of his claims in connection with the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway, $300,000 of which would line the coffers of the Liberal election campaign fund. On 30 April Tarte disclosed the Quebec Harbour Commission scandal, using the testimony given by Murphy and by Robert McGreevy. The McGreevy affair was front-page news. On 5 May “Uncle Thomas” – today he would be called the Godfather – had Tarte arrested for libel and on 14 May he sued him for $50,000 in damages, but in vain. The fire Tarte had lit was spreading. It reached the Langevin–McGreevy duo and then the Conservative party. Various dealings to hush up the affair delayed the dénouement just long enough for Mercier to be returned to power in Quebec on 17 June 1890, and for Macdonald to lead his troops to one last victory in the spring of 1891. When the commons met that May the McGreevy affair was on the agenda. Tarte drew up a list of 63 charges on 11 May. On 26 May the house appointed a committee, and its investigations, interrupted briefly by Macdonald’s death on 6 June, led to the disclosure of the Baie des Chaleurs Railway scandal in the Senate on 4 August, Langevin’s resignation on 11 August, and the expulsion of McGreevy from the commons on 29 September.

With this expulsion, McGreevy’s downfall was complete. When his suit against his brother was dismissed by the Court of Queen’s Bench, leaving him no further hope of compensation for his railway activities, he was financially ruined. He rented his property on Rue d’Auteuil to Andrew Hunter Dunn, the Anglican bishop of Quebec, and transferred the rental income to one of his creditors. His brother Robert was convicted and sent to jail in May 1892. He himself and Nicholas Knight Connolly, charged with conspiring to defraud the public treasury of more than $3,000,000, were sentenced to a year in prison and began serving their terms in the Ottawa district jail on 22 Nov. 1893. Their sentences were commuted on 1 March 1894 by Governor General Lord Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon*], on the basis of a favourable opinion by cabinet, which had consulted two doctors and taken steps to destroy any documents that might compromise members of the Conservative party. After his release from prison, McGreevy fought one last-ditch battle to save his honour: he won back his seat in the Quebec West by-election of 1895, but, like most of his Conservative colleagues, he was defeated in the general election of 1896. Shortly afterwards, on 2 Jan. 1897, he died of heart failure, leaving no will. His widow and three surviving children renounced their claim to the estate, which was heavily mortgaged.

Historians have identified various political consequences of the McGreevy scandal: it put Langevin out of the running to succeed Macdonald; it paved the way for Wilfrid Laurier*’s rise to power; it forced the commons to pass legislation dealing with relations between contractors and the government; finally, it lent credence to the legend that corruption was more deeply ingrained in political life in Quebec than elsewhere in Canada. Few historians, however, have considered this affair – or the others of a similar kind – as a sign of the changes affecting Canadian political life in the mid 19th century, and of the factors influencing these changes. Canadian liberal democracy took shape at the time Canada was moving from a feudal to a capitalist system, and from a colonial to an autonomous society. With industrialization and the railway, modern social classes made their appearance, and with these classes came responsible government and the system of tightly knit and affluent political parties as the instrument of dominant groups. The outlook implicit in Sir Allan Napier MacNab*’s quip in 1851 – “All my politics are railroads” – ushered in a new era that saw a redefinition of relations between classes and power, capitalists and politicians, ethics and politics. During the 19th century these questions were not widely debated by the public; they were brought up on occasion by journalists and touched upon in the commons, but never discussed in depth. Thus a spoils system was put in place, with public funds being diverted for the use of dominant groups. Such groups made Thomas McGreevy – “by far the most honest man of the lot,” according to Sir Richard John Cartwright* – their instrument and scapegoat.

AC, Québec, État civil, Catholiques, St Patrick’s Church, 4 Jan. 1897; Minutiers, Philippe Huot, 29 nov. 1866; William Bignell, 30 janv., 27 août, 26 oct. 1869; 27 janv. 1870. ANQ-Q, CE1-1, 31 juill. 1825, 30 janv. 1867; CE1-58, 4 févr. 1861; E17/23, no.1593; P-134; P1000-67-1348; T10-1/29, 56, 76; T11-1/1030. ASQ, Séminaire, 230, no.159. AVQ, Conseil, conseil de ville, procès-verbaux, 1861–63. NA, MG 26, D, 193, 201; MG 29, D36; RG 13, A3, 656. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1870; 6–7, 16 May 1890; 11, 13, 27 May 1891. Canadian Architect and Builder (Toronto), 6 (1893): 122. Que., Legislative Council, Journals, 1868–73. Le Canadien, 1er févr., 30 avril, 18, 20, 25 sept., 1er–2, 7–8oct., 1er nov.–4déc. 1890. L’Électeur, 11, 17 nov. 1893; 2 mars 1894. Gazette (Montreal), 4 Jan. 1897. Montreal Daily Star, 4 Jan. 1897. Quebec Daily Mercury, 2, 5 Jan. 1897. Canadian biog. dict., 2: 341–42. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson), 411. CPC, 1867–96. Geneviève Guimont Bastien et al., Inventaire des marchés de construction des archives civiles de Québec, 1800–1870 (3v., Ottawa, 1975). Langelier, Liste des terrains concédés, 1664. Quebec directory, 1847–97. A. J. H. Richardson et al., Quebec City: architects, artisans and builders (Ottawa, 1984). Wallace, Macmillan dict. Lucien Brault, Ottawa old & new (Ottawa, 1946). Christina Cameron, L’architecture domestique du Vieux-Québec ([Ottawa], 1980); “Charles Baillairgé, architect (1826–1906)” (thèse de phd, univ. Laval, Québec, 1982). R. [J.] Cartwright, Reminiscences (Toronto, 1912). Davin, Irishman in Canada. Désilets, Hector-Louis Langevin. Gervais, “L’expansion du réseau ferroviaire québecois.” L. L. LaPierre, “Politics, race and religion in French Canada: Joseph Israël Tarte” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1962). Michel Stewart, “Le Québec, Montréal, Ottawa et Occidental, une entreprise d’État, 1875–1882” (thèse de phd, univ. Laval, 1983). Waite, Canada, 1874–96; Man from Halifax. S. E. Woods, Ottawa, the capital of Canada (Toronto and Garden City, N.Y., 1980). B. J. Young, Promoters and politicians. “Les disparus,” BRH, 39 (1933): 511. L. L. LaPierre, “Joseph Israël Tarte and the McGreevy–Langevin scandal,” CHA Report, 1961: 47–57.

Cite This Article

Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin, “McGREEVY, THOMAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 9, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcgreevy_thomas_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcgreevy_thomas_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin |

| Title of Article: | McGREEVY, THOMAS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | March 9, 2026 |