Source: Link

LALEMANT, CHARLES, first superior of the Jesuits of Quebec (1625–29), missionary at Quebec (1634–38), procurator of the mission of New France, in Paris (1638–50), son of a criminal court lieutenant of Paris; brother of Jérôme Lalemant; b. 17 Nov. 1587; d. 18 Nov. 1674 in Paris.

Charles Lalemant entered the noviciate at Rouen on 29 July 1607. He studied philosophy at the Collège in La Flèche (1609–12), taught the lower classes at the Collège in Nevers (1612–15), studied his theology at La Flèche (1615–19), and did his third probationary year in Paris under the direction of the celebrated Father Antoine Le Gaudier (1619–20). He was then a teacher of logic and physics at the Collège of Bourges (1620–22), and from October 1622 to March 1625 was principal of the boarding-school at the Collège de Clermont.

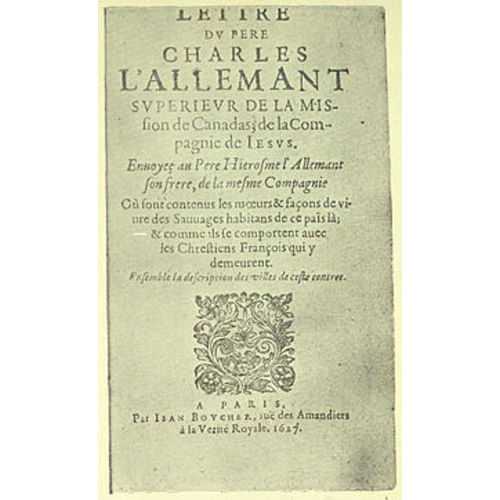

He was made responsible for setting up a mission of the Society of Jesus in Canada, and in April 1625 he left Dieppe with Fathers Énemond Massé, Jean de Brébeuf and two lay brothers. He arrived at Quebec in June. Neither the directors of the Compagnie de Montmorency nor the settlers amongst whom the pamphlet Anti-Coton was then circulating had any liking for the Jesuits. But the Recollets received them with great kindliness and gave them hospitality until they could have their own house. Father Lalemant was quick to realize that the progress of the colony was being impeded by the very people who ought to have promoted it, the de Caëns, who were interested exclusively in the fur trade. A change was imperative. Therefore, as soon as Father Philibert Noyrot arrived in 1626 he was ordered, because of the good standing that he enjoyed at the court, to take ship again for France, with the object of advancing the welfare of the colony. One result of this move was the revocation of the Edict of Nantes where New France was concerned. Father Noyrot had arranged for supplies to be sent to his Quebec colleagues, but they never reached their destination. According to Father Chrestien Le Clercq, they were seized at Honfleur by Raymond de La Ralde and Guillaume de Caën. Hence Father Lalemant returned to France in the autumn of 1627. The ship that was bringing him back to Canada in 1628, and that was commanded by Claude Roquemont de Brison, fell into the hands of the Kirke brothers. The latter made Lalemant their prisoner and dispatched him to Belgium, whence he got back to France. A fresh start, made in 1629, was interrupted by a shipwreck in the Strait of Canseau. Lalemant had to return to France on a Basque fishing vessel which was itself wrecked near San Sebastián in Spain [JR (Thwaites), IV, 229–44]. These were personal misfortunes, to be superseded in the apostolic soul of Father Lalemant by a greater one: Quebec was in the hands of the English, and what the missionaries had accomplished was already overthrown.

But Lalemant lost no time in setting to work to restore the ruins. He launched crusades of prayer in the Paris monasteries; as rector of the Collège in Eu, then of the Collège in Rouen, he followed closely the negotiations which were to culminate in the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1632). By December 1631 he was convinced that Canada would be given back to France, and he asked to return to the colony. His wish was not to be granted until 1634, and he was to return to France for good in 1638. It was he who helped Champlain during his last illness and who celebrated the funeral mass. A letter that he addressed to his brother Jérôme Lalemant, on 1 Aug. 1626, reveals the soul of the man. He was, under no illusions as to the difficulties of the missionary apostolate: “The conversion of the Savages takes time. The first six or seven years will appear sterile to some; and, if I should say ten or twelve, I would possibly not be far from the truth. But is that any reason why all should be abandoned? Are not beginnings necessary everywhere? Are not preparations needed for the attainment of every object? For my part, I confess that, if God shows me mercy, although I expect no fruits as long as it will please him to preserve my life, provided that our labours are acceptable to him, and that he may be pleased to make use of them as a preparation for those who will come after us, I shall hold myself only too happy to employ my life and my strength, and to spare nothing in my power, not even my blood, for such a purpose.” These words reveal a clear grasp of the difficulties, linked with the spiritual strength to overcome them: Precious qualities in the founder of a mission. He did not labour in vain. The residence that he had built at Quebec was to receive Father Paul Le Jeune in 1632, and he was to live there himself from 1634 to 1638. Indeed, Father Lalemant’s zeal was particularly manifest in his efforts on behalf of the French population of Quebec. He had left such pleasant memories there those 12 years after his departure the Communauté des Habitants was to recommend him to the queen as the first bishop of Quebec.

In 1626 when Father Lalemant reported to the general of the Society Father Noyrot’s return to France, he said that the object of his voyage was to inform certain benefactors and even his colleagues in Paris about the needs of the Jesuit mission in New France. Lalemant added that, after the return of Father Noyrot in the spring, it would be necessary to replace him with a person who would look after the interests of the Canadian mission in France. What Father Lalemant was suggesting was a procurator for the mission, a post that he was to be the first to hold and that would allow him to play a very important part in the founding of Montreal. It was through his personal intervention with M. Jean de Lauson, the future governor of New France, that the island was ceded to the Société de Montréal. It was he who introduced Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve to Jérôme Le Royer de La Dauversière. He likewise had a decisive influence in bringing Jeanne Mance, Louis d’Ailleboust de Coulonge, and his wife Marie-Barbe de Boullongne to Montreal.

Father Lalemant’s ministry, like that of his successors in Paris, Fathers Le Jeune and Paul Ragueneau, was devoted to preaching and spiritual leadership. In 1660 he published La vie cachée de Jésus-Christ en l’eucharistie, which was reprinted in 1835, 1857, and 1888. Father Lalemant died in Paris 18 Nov. 1674, at the age of 84. His contribution to Canadian history, if less spectacular than that of men such as Le Jeune and Ragueneau, is very important. In particular, he occupies a distinguished place in the gallery of people who never saw Montreal, but among whom one must seek the explanation of its heroic origins.

It is known that Father Charles Lalemant had been the superior of the professed house in Paris, and for a time vice-provincial. It was in this capacity that he authorized Cramoisy, on 3 February 1652, to publish the 1651 Relation.

Father Lalemant was an unflagging correspondent. His letter of 1 Aug. 1626 to Father Jérôme was the 68th of that year, and it was not the last. What has become of them? We do not know.

Le Clercq, First establishment of the faith (Shea); Premier établissement de la foy. E. R. Adair, “France and the beginnings of New France,” CHR, XXV (1944), 246–78. Campbell, Pioneer priests, II, 247–76. Robert Le Blant, “Le testament de Samuel de Champlain, 17 novembre 1635,” RHAF, XVII (1963–64), 273–77. In Ville, ô ma ville (Montréal, 1941), 63–71, the author has described the part played by Father Charles Lalement in the founding of Montreal. Rochemonteix, Les Jésuites et la Nouvelle-France au XVIIe siècle, I, 137f.

Cite This Article

Léon Pouliot, “LALEMANT, CHARLES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lalemant_charles_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lalemant_charles_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Léon Pouliot |

| Title of Article: | LALEMANT, CHARLES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | February 19, 2026 |