MacBETH, RODERICK GEORGE, lawyer, Presbyterian minister, author, historian, and lecturer; b. 21 Dec. 1858 in Kildonan (Winnipeg), Red River settlement (Man.), son of Robert McBeath*, a farmer and member of the Council of Assiniboia, and Mary McLean; m. first 21 Aug. 1886 Christina Ellen (Minnie) Sutherland in Kildonan, and they had a son; m. secondly 3 June 1896 Elizabeth (Libbie) Patterson in Oakville, Ont., and they had three daughters; d. 28 Feb. 1934 in Vancouver.

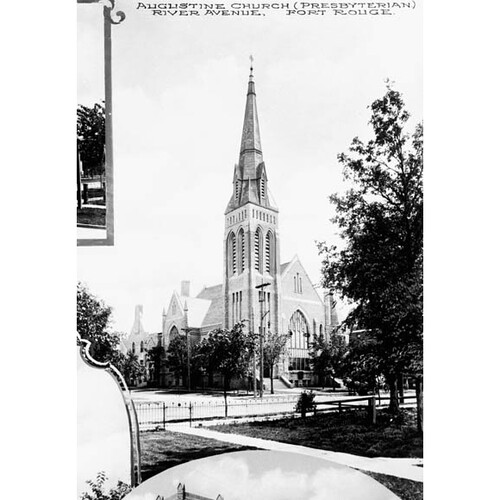

As a son of Scottish immigrants brought to the Red River settlement by Lord Selkirk [Douglas*] in 1815, Roderick MacBeth was among the early generations of settlers in what would become western Canada. His life there provided him with an invaluable perspective on the evolution of the area. After an education in local parish schools, he attended the University of Manitoba, from which he obtained a ba in 1882 and an ma in 1885. Although he was called to the bar in 1886, he soon abandoned law for religion. Graduating from Princeton Theological Seminary in 1891, he was ordained a Presbyterian minister that year, and for the next decade he served congregations in Manitoba, first in Carman and then in Winnipeg, at Augustine Presbyterian Church. In 1900 he moved to Vancouver, where he took over First Presbyterian Church. From 1904 to 1914 he was in Paris, Ont., and then he returned to Vancouver to accept a call from St Paul’s Presbyterian Church, where he stayed until his retirement in 1932.

Known for his keen powers of observation and his excellent memory, MacBeth exhibited a strong and forceful personality, tempered with what would be described in the obituary by the Synod of British Columbia as a “genial and generous disposition.” According to the same source, his strengths as a clergyman included “splendid preaching” and attentive visitation. As a proponent of the Social Gospel, he campaigned against rising criminality, rampant materialism, and behaviour such as swearing and gambling, and promoted temperance and the restriction of commercial activity on Sundays. He prepared reports for the Presbyterian home mission board on the tasks confronting the church in such frontier areas as the newly opened mining region around Cobalt in northern Ontario and in western Canada. Some of his reports were later published for wider distribution under the titles Our task in Canada (Toronto, 1912) and Empire of the north (Toronto, [1912]). Believing that the nation would perish without spirituality and the support of churches, he worried about the challenge of assimilating new immigrants into Canadian society and instilling in them proper values and beliefs. As a proud Scot who championed independence and freedom, he favoured an autonomous Presbyterian church during discussions on the union of the major Protestant denominations in Canada. After the amalgamation of some Presbyterian congregations into the new United Church of Canada in 1925 [see Clarence Dunlop Mackinnon], he wrote The burning bush in Canada (Toronto, [1926?]) to provide guidance and encouragement for the continuance of a separate Calvinist church in the Scottish tradition [see Ephraim Scott].

Following consciously in the steps of such notables as Alexander Ross*, Donald Gunn*, and Alexander Begg* (1839–97), who had all recorded the history of the Red River settlement and the fur trade, MacBeth recounted his memories of growing up in the region. Unlike his predecessors, however, he carried his histories into the 20th century and enlarged his scope to encompass a pan-Canadian perspective. Celebrating the tradition of the peaceful development of the nation from its colonial roots, he wrote as a pioneer and a clergyman, but he supplemented his first-hand information with historical research. His purpose, stated in The romance of western Canada (Toronto, 1918), was to produce “not a dry encyclopaedia but a living, reminiscent history of the people.” He wrote in a liberal, national tradition of the heroic; in The romance of the Canadian Pacific Railway (Toronto, 1924), he explained that “the coming generation must not miss the tonic power that comes from a knowledge of great achievement in a nation’s life.”

The scope of the personal experience recounted in MacBeth’s works is remarkable. He was 11 years old during the Red River rebellion and he remembered its leader, Louis Riel*. The head of the Canadian party, which demanded the colony’s annexation to Canada, John Christian Schultz*, fled to the MacBeth home in Kildonan in January 1870 after escaping from Riel’s forces. A law student during the North-West rebellion of 1885, MacBeth served as a lieutenant in the Winnipeg Light Infantry Battalion under the command of William Osborne Smith*. Following his return to Winnipeg, he attended the appeal hearing that questioned the jurisdiction of the Regina court where Riel’s trial had been held. Later the same year he was among those who rushed to St Boniface (Winnipeg) to prevent any disruption of Riel’s burial. In 1886 MacBeth heard Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* speak during his first visit to the west. Sir Donald Alexander Smith*, governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company and high commissioner to London, was a family friend who wrote the introduction to MacBeth’s The Selkirk settlers in real life (Toronto, 1897). When the first group of Doukhobors arrived in Winnipeg in 1899 [see Peter Vasil’evich Verigin*], MacBeth interviewed them through an interpreter. He toured the mining country of northern Ontario and followed the path used by explorer Alexander Mackenzie* on his 1793 journey to the Pacific Ocean.

In his works MacBeth interprets events, but his handling of often controversial evidence is balanced and non-judgemental. “Let the reader follow the story,” he advises in The romance of western Canada, “and arrive at a verdict.” He places emphasis on the social history of the Red River settlement, and pays special attention to religion and education. Although he disapproves of the Riel rebellions of 1869 and 1885, he acknowledges the legitimacy of the grievances and the mistakes made by both sides, especially criticizing those in positions of authority for their lack of knowledge of western conditions and their failure to communicate their intentions. Language and educational disputes, such as the Manitoba school question [see Thomas Greenway*] and the North-West school question [see Adélard Langevin*], receive similar restrained treatment, but MacBeth was strongly in favour of a single, non-sectarian public school system. The exception is his description of Selkirk, whom he characterizes as “a rescuing angel” to dispossessed Scots who held his name “in sacred memory.” Macbeth also became a popular public speaker; the subjects covered in his published works provided material for numerous lectures. In addition, he addressed audiences on the lives of Abraham Lincoln and William Ewart Gladstone as well as other historical topics.

In the 1920s MacBeth expanded the period covered by his works to include the history of the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Royal North-West Mounted Police (covering its transformation into the Royal Canadian Mounted Police), thus completing his portrayal of the prairies’ contribution to nation building. This focus on the Red River settlement, Riel, the CPR, and the mounted police remains a central part of Canada’s historiographical fabric. However, unlike many who would tell the CPR story, MacBeth continued his account into modern times, chronicling the construction of spiral tunnels, dams, aqueducts, and urban real-estate development. Hoping that his history of the mounted police would “deepen in all men of sincerity a respect for authority in a restless age,” he credits the police force with preventing the prairies from descending into anarchy. Yet, as in his other works, he presents a story without romantic haloes and with many vignettes of the historical record. His books earned him an honorary lld from the University of Manitoba in 1929. The honour guard of 12 red-coated members of the RCMP at his funeral in Vancouver in 1934, along with pipers from the Seaforth Highlanders and a contingent of city policemen, was another testament to the respect in which MacBeth and his writings were held by the public.

A large number of Roderick George MacBeth’s works can be found in the Univ. of Alta Libraries database under the title “Peel’s prairie provinces,” and can be consulted online at www.peel.library.ualberta.ca. Other titles are listed in the LAC catalogue.

AO, RG 80-5-0-234, no.5078. BCA, GR-2951, no.1934-09-489349. Man., Dept. of Tourism, Culture, Heritage, Sport and Consumer Protection, Vital statistics agency (Winnipeg), no.1886-001923. J. M. Bumsted, Dictionary of Manitoba biography (Winnipeg, 1999). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Presbyterian Church in Can., Synod of B.C., Acts and proc. (New Westminster, B.C.), 1934: 270–71. “Rev. R. G. MacBeth, d.d., ll.d.: further tributes,” Presbyterian Record (Toronto), 59 (1934): 143–44. Wallace, Macmillan dict.

Cite This Article

Clarence Karr, “MacBETH, RODERICK GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 22, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macbeth_roderick_george_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macbeth_roderick_george_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Clarence Karr |

| Title of Article: | MacBETH, RODERICK GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2015 |

| Year of revision: | 2015 |

| Access Date: | February 22, 2026 |