![[Vers 1880] Original title: [Vers 1880]](/bioimages/w600.14911.jpg)

Source: Link

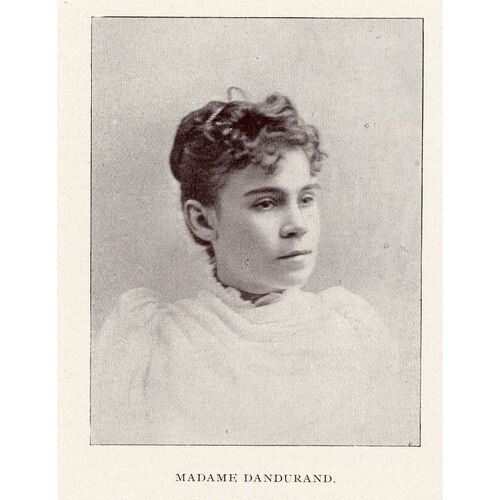

MARCHAND, JOSÉPHINE (baptized Joséphine-Hersélie-Henriette) (Dandurand), journalist, writer, lecturer, and feminist activist; b. 5 Dec. 1861 in Saint-Jean (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu), Lower Canada, daughter of Félix-Gabriel Marchand* and Hersélie Turgeon; m. there 12 Jan. 1886 Raoul Dandurand*, and they had one daughter; d. 2 March 1925 in Montreal and was buried there in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery.

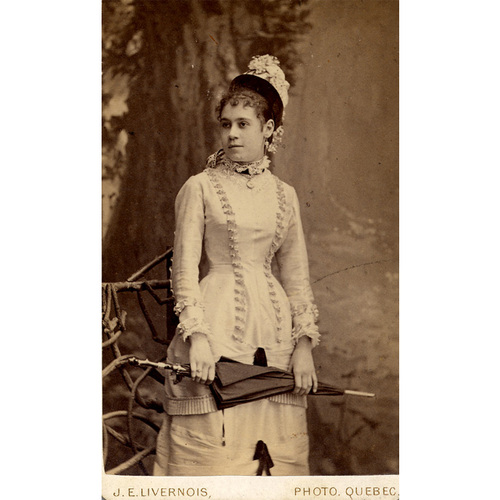

One of a family of 11 children, Joséphine Marchand spent her early years in Saint-Jean. Because she was fidgety, she was nicknamed Froufrou, but in her adult years she would be calm and reserved. Her father, Félix-Gabriel, was a notary by training. In 1860, with Charles Laberge* and Isaac Bourguignon, he had founded a Liberal semi-weekly in Saint-Jean known as Le Franco-Canadien. From 1867 he represented the riding of Saint-Jean in the Legislative Assembly. After pursuing a career both in politics and in letters, he would become premier of Quebec on 24 May 1897. Joséphine’s mother, Hersélie, had been educated at the Couvent de Saint-Roch at Quebec, and loved to read. She unquestionably belonged to one of the most prominent Quebec families of the time.

In this privileged environment, Joséphine acquired a taste for literature very early. Educated in her native city, with the Sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, she was a talented pupil, and is thought to have won a prize for English literature. She adored the French language, but also mastered English, which she would sometimes use in her private diary and in public lectures. Arthur Buies*, Louis Fréchette*, and Benjamin Sulte were among her favourite Canadian writers, and among French ones she was especially fond of Alphonse de Lamartine, Victor Hugo, and Guy de Maupassant. She also read Spanish and English literature.

Joséphine Marchand began to write for publication in 1879. Over the next 12 years her work, usually in the form of short stories and tales, would appear in Le Franco-Canadien, of which her father was editor, and the Montreal newspapers La Patrie and L’Opinion publique; Honoré Mercier*, a family friend, insisted on representing her in her dealings with the latter. Her private diary, begun at the age of 17, is a valuable document, both for the information it contains and for the picture it provides of her. (Her husband would be unaware of its existence until after her death.) Among other things, the young woman tells of the curiosity her by-line aroused. In truth, at the time she began writing few women were trying their hand at literary endeavours in French Canada. Until then, Félicité Angers, known as Laure Conan, had been almost the only one. From the outset of Joséphine’s career, her father, who was her first reader and critic, acknowledged that she showed a certain facility of expression, but he maintained, according to her private diary, that she would have to “work very seriously to eliminate many stylistic shortcomings.”

On 12 Jan. 1886, in the parish of Saint-Jean-l’Évangéliste in Saint-Jean, Joséphine Marchand married Raoul Dandurand, who described himself at the time as a gentleman and lawyer. For their honeymoon they went to New York. Their only daughter, Gabrielle, was born in December of that year. In 1891 they would use all their ready money ($2,000) for a five-month stay in Europe. Over the years Joséphine would take at least six more trips overseas, travelling to France, England, Germany, Austria, and Italy. A Liberal in politics, Raoul Dandurand was appointed to the Senate in 1898, assuming a heavy responsibility for a young man of 36. In his memoirs, which were to be published in 1967, he told of Joséphine’s influence, claiming that he would not have been made a senator had it not been for her prestige and the affection she inspired in the people who met her.

Joséphine Dandurand enjoyed great success with her writing. In 1888 a performance of “Quand on s’aime, on se marie” at the Académie de Musique de Québec aroused public interest. This one-act comedy in prose would come out in 1896 with the title Rancune. In 1889 she published Contes de Noël under the pseudonym Josette, which she had been using since she began to write. With a preface by Fréchette, it was a collection of eight stories that had previously appeared in magazines. According to Fréchette – a man of his times – the style of the stories revealed “the author’s femininity” hidden behind the pseudonym. She then brought out two short children’s plays, Ce que pensent les fleurs in 1895 and La carte postale the following year. All four of these works were published in Montreal.

In January 1893 Dandurand founded Le Coin du feu in Montreal. With the inauguration of this monthly magazine she established a secure place for herself in the field of journalism. Le Coin du feu was the first French-language periodical in Canada edited by a woman and intended specifically for women. Although she could occasionally count on prestigious contributors – Félicité Angers, Marie Gérin-Lajoie [Lacoste*], Jules Simon, and Paul Bourget – as founder and editor she herself produced much of the material: a leading column signed with her married name, Mme Dandurand; columns titled “Travers sociaux,” signed Marie Vieuxtemps and devoted to dissecting the shortcomings of middle-class society; and the articles by Météore, in which she dealt with literature and the French language. This forum enabled her to explore her favourite topics, including literature, family relationships, feminism, the intellectual awakening of women, and politics. In December 1893, for example, she published the opinions of a number of people, including her mother, Félicité Angers, Joseph-Israël Tarte*, and Arthur Buies, on the subject of women’s suffrage. Regular columns on cooking, fashion, hygiene, and health, as well as articles for children, poems, and illustrations, were included in the 30-odd pages of each number.

In the last issue of Le Coin du feu, which appeared in December 1896, Dandurand published an appeal for a flourishing women’s press. “For the experiment has been done. A women’s publication dealing with private family concerns – material as well as intellectual and moral – is timely and desirable in our society.” In order to justify this opinion, she mentioned her “inability to devote to journalism all the time and effort necessary for this difficult profession.” She then began writing for other Montreal publications, including Le Monde illustré (1898–1900), Le Journal de Françoise (1902–9), and La Revue moderne (1920–21). In 1901, in Montreal, she assembled 44 of her early newspaper items and two lectures in an anthology to which she gave the title Nos travers. This volume would be republished in 1924.

Along with her activities as a woman of letters, Dandurand was involved in a number of organizations. In the spring of 1894 she began a career as a public speaker, in English, at the first annual congress of the National Council of Women of Canada, which was held in Ottawa. At the conclusion of her talk on literary clubs, she expressed a wish for closer harmony between Canada’s two linguistic groups. She subsequently became very active as a speaker and her eloquence even earned her the nickname “the female Laurier.” She would be provincial vice-president of the National Council of Women of Canada (1912–13, 1917–19); within its Montreal branch she held the offices of vice-president (1895–96, 1900–1, 1906–7), member of the presidential board (1903–7), and honorary vice-president (1918–21). In 1898 she founded the Œuvre des Livres Gratuits, which provided reading matter for teachers in remote areas and people from underprivileged backgrounds. In March that year the French government awarded her the title of officier d’académie, in recognition of her defence of French culture in North America. Along with her fellow writer Robertine Barry*, known as Françoise, she represented Canadian women at the universal exposition in Paris in the summer of 1900. She was also one of the patronesses who in 1902 founded the women’s section of the Association Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal [see Jeanne Anctil].

The feminist movement “is an awakening of women to responsibility. . . . In the land as in the family, the voice of women must communicate the reassuring words that recall [us] to duty and to humanity,” declared Dandurand in the course of a lecture reprinted in Nos travers. At the heart of her feminism was above all the responsibility to develop the mind. This was the goal of her various undertakings, and indeed of her marriage, to which she chose to give the motto “Knowledge, intelligence before love!” After 1907, already overtaken by illness, she slowed the pace of her activities and less and less often wrote columns. Familiar with the world of politics, she remained closely associated with the work of her husband, who had been appointed speaker of the Senate in 1905. Astute and ambitious, she was also able to use her influence with key individuals, including Sir Wilfrid Laurier*, to advance Raoul Dandurand’s career. Active all her life, she died in Montreal on 2 March 1925, following a lengthy illness, at the age of 63.

[In addition to the works mentioned above, Joséphine Marchand (Dandurand) is the author of the chapter “French Canadian customs” in National Council of Women of Canada, Women of Canada: their life and work; compiled . . . for distribution at the Paris international exhibition, 1900 ([Montreal?, 1900]; repr. [Ottawa], 1975), 22–30. She is also the author of a lecture, “Le français dans nos relations sociales,” published in Premier congrès de la langue française au Canada, Québec, 24–30 juin 1912: compte rendu (Québec, 1913), pp.537–40. For many years she kept a diary which has been published as Journal intime, 1879–1900, Edmond Robillard, édit. (Lachine, Qué., 2000); the original is in LAC, MG 27, III, B3. Joséphine Marchand also wrote articles in various periodicals; beyond those mentioned in the biography, they include Le Journal du dimanche (Montréal), 1884, Le Canada artistique (Montréal), 1890, L’Alliance nationale (Montréal), 1899, and La Bonne Parole (Montréal), 1920. The contributor has compiled a partial list of Marchand’s articles, a copy of which is available at the DCB. An inventory of her writings also appears in Laurette Cloutier, “Bio-bibliographie de madame Raoul Dandurand (née Joséphine Marchand)” (école de bibliothécaires, univ. de Montréal, 1942). l.g.]

ANQ-M, CE604-S10, 6 déc. 1861, 12 janv. 1886. ANQ-Q, P174. Gazette (Montréal), 3 March 1925. La Patrie, 31 mai 1902. Anita, “Mme Dandurand,” La Bonne Parole, 14 (1926), no.2: 10. BCF, 1923: 157. Georges Bellerive, Brèves apologies de nos auteurs féminins (Québec, 1920). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Raoul Dandurand, Les mémoires du sénateur Raoul Dandurand (1861–1942), Marcel Hamelin, édit. (Québec, 1967). La Directrice [Robertine Barry], “Madame la présidente du Sénat,” Le Journal de Françoise (Montréal), 3 (1904–5): 611. DOLQ, 2: 775–76. Sylvain Forêt, “Bibliographie; littérature canadienne,” Le Canada artistique, 1, no.1 (prospectus, décembre 1889): 8–9. Lionel Fortin, Félix-Gabriel Marchand (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Qué., 1979). Françoise [Robertine Barry], “French Canadian women in literature,” in Women of Canada: their life and work, 190–97. Hamel et al., DALFAN, 361–62. Madeleine [A.-M.] Gleason-Huguenin, Portraits de femmes ([Montréal], 1938), 98–99. Yolande Pinard, “Les débuts du mouvement des femmes à Montréal, 1893–1902,” in Travailleuses et féministes: les femmes dans la société québécoise, sous la dir. de Marie Lavigne et Yolande Pinard (Montréal, 1983), 177–98. Diane Thibeault, “Premières brèches dans l’idéologie des deux sphères: Joséphine Marchand-Dandurand et Robertine Barry, deux journalistes montréalaises de la fin du XIXe siècle” (thèse de ma, univ. d’Ottawa, 1981).

Cite This Article

Line Gosselin, “MARCHAND, JOSÉPHINE (baptized Joséphine-Hersélie-Henriette) (Dandurand),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 12, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/marchand_josephine_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/marchand_josephine_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Line Gosselin |

| Title of Article: | MARCHAND, JOSÉPHINE (baptized Joséphine-Hersélie-Henriette) (Dandurand) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | March 12, 2026 |