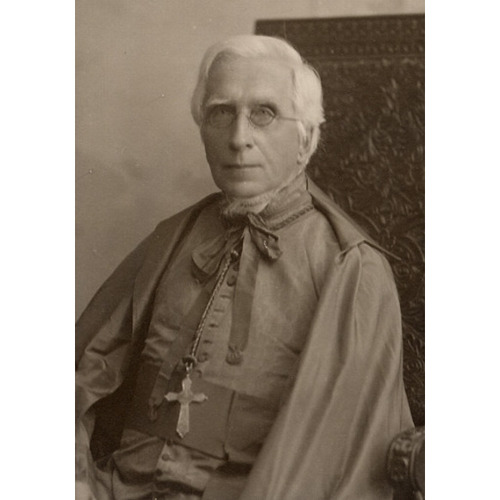

![Joseph-Calixte Marquis, [Vers 1880], Archives nationales à Québec, Fonds J. E. Livernois Ltée, (03Q,P560,S2,D1,P861), J.E. Livernois Photo. Québec. Original title: Joseph-Calixte Marquis, [Vers 1880], Archives nationales à Québec, Fonds J. E. Livernois Ltée, (03Q,P560,S2,D1,P861), J.E. Livernois Photo. Québec.](/bioimages/w600.25538.jpg)

Source: Link

MARQUIS, CALIXTE (baptized Joseph-Calixte Canac, dit Marquis), Roman Catholic priest, colonizing missionary, and protonotary apostolic; b. 14 Oct. 1821 at Quebec, son of David Marquis (Canac, dit Marquis), a merchant, and Euphrosine Goulet; d. 19 Dec. 1904 in Saint-Célestin, Que.

After completing his classical studies at the Petit Séminaire de Québec (1831–39) and his theological education at the Grand Séminaire de Québec (1840–44), Calixte Marquis was ordained priest on 21 Dec. 1844. In the autumn of 1845 he became curate at Saint-Grégoire (Bécancour), where he distinguished himself by his zeal. In 1847 he set about finding homes for 33 Irish orphans in Saint-Grégoire and Bécancour, and he helped pay for the schooling of four of them, two boys and two girls. Along with his parish priest Jean Harper, he grappled with educational problems; as secretary-treasurer of the school board he had to face a large group of people who would not contribute financially to the schools and who even burned down a barn and poisoned his mare. From 1849 to 1853, in close collaboration with his superior, he laid the foundations for a community of teaching nuns, the Sisters of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin; he claimed the title of founder, but it was disputed by those supporting Harper [see Edwige Buisson].

From his earliest days in Saint-Grégoire Abbé Marquis had taken an interest in the colonization of the Eastern Townships. He became more actively involved in the issue when in 1852 he was made parish priest of Saint-Célestin, with responsibility for “all the faithful . . . in Aston Township.” Despite delicate health, which frequently confined him to his residence, he went about the missions – serving as many as eight at one time – and he helped found 12 parishes. In these emerging settlements he added to his pastoral tasks those of local leadership, in order, he said, “to supervise the building of religious edifices [and] the opening of roads, to intervene between the settlers and the Department of Lands or the big landowners if necessary, to be notary, doctor, postmaster, justice of the peace, etc.” He participated regularly in municipal and school affairs, and he was not afraid to support certain Liberal candidates openly; he even thought of running in the federal election of 1877, but Bishop Louis-François Laflèche* of Trois-Rivières demurred. Acting unofficially as land agent, he bought a great many properties, among the most fertile and best located, and then sold them to settlers at a good profit, a procedure that gave rise to accusations of speculation and even dishonesty.

In this period Abbé Marquis showed himself one of the keenest of those theorizing about colonization: he denounced obstacles such as the absence of roads, the speculation of large landowners, and the lack of religious succour, and in 1857 and 1867 he put forth overall plans to correct the situation. His key idea was to make the clergy “the vehicle for colonization” and to ensure its leadership in the Eastern Townships by creating a diocese at Nicolet.

He was to pursue this project for more than 30 years. In 1852, along with a group of priests from the south shore of the St Lawrence, he asked that Nicolet, rather than Trois-Rivières, be chosen for the residence of the new bishop being sought by the Canadian episcopate. In 1867 he returned to the attack with a proposal that a diocese be carved out of those of Quebec and Trois-Rivières, to consist of the region south of the St Lawrence minus the old parishes along the river’s edge. For the episcopal town it was possible to find “a central place,” with “a church and residence suitable for receiving a bishop,” and even a college: none other than Nicolet. The creation of the diocese of Sherbrooke in 1874 did not fit with the colonizing missionary’s plans.

Abbé Marquis then teamed up with the priests of the Séminaire de Nicolet; these priests, anxious about the survival of their institution ever since Bishop Laflèche had raised the Collège de Trois-Rivières to a diocesan seminary in 1874, were asking Rome to split the diocese of Trois-Rivières and create a diocese of Nicolet. His support, given discreetly at first, changed into a full-blown campaign upon the arrival of an apostolic delegate, Bishop George Conroy*, in 1877. Laflèche denounced Marquis as “the heart and soul of all this agitation,” and Conroy described him as a “base schemer.” In the summer of that year Laflèche seized upon a complaint by some parishioners in Saint-Célestin to remove Marquis from “the theatre of his intrigues and the main communication routes . . . and from a population afraid of him, many of whom doubt his honesty.” Marquis refused to be transferred to Sainte-Ursule and withdrew from active ministry; from then on he lived in a small house opposite the church of Saint-Célestin. The announcement in April 1878 that no new diocese would be established at Nicolet forced him to ask Laflèche for some means of subsistence, which became a bone of contention between the two men for some years. In 1883 the former curé was licensed as a priest to serve in the diocese of Chicoutimi, whose bishop was his friend Dominique Racine*; he continued to reside in Saint-Célestin.

Taking advantage of his newly acquired “spare time,” Abbé Marquis had begun work on another petition to the Holy See pleading the cause of Nicolet; it was completed in August 1881 but was not presented to the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda until December 1882. He himself went to live in Rome in 1882 and steered the case through the help of a network of friends within the Roman congregations; he sent information back to his supporters in Canada, and he provided the Holy See with a mass of documents and commentaries. Skilfully demolishing the principal arguments of those who opposed Nicolet, he systematically denigrated Bishop Laflèche and his agent Luc Desilets*. Despite the objections of apostolic delegate Joseph-Gauthier-Henri Smeulders, he succeeded in getting Nicolet made into a diocese in 1885, thanks to the support of a majority of the Quebec bishops and the powerful intervention of Archbishop Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau*. Canon Elphège Gravel, of Saint-Hyacinthe became the first bishop.

Marquis then returned to Saint-Célestin, crowned with titles: founder of the new diocese, protonotary apostolic ad instar participantium, and even honorary canon of the basilicas of Loreto and Verona in Italy. He also brought back many relics that he is believed to have taken from the catacombs of Rome and the chapel of the Odeschalchi family. He distributed many of them among the parishes that requested some, but also kept many in his home. Later brought together in 226 reliquaries, 6,200 relics formed the ornamentation of the first Tour des Martyrs, a chapel built in Saint-Célestin by Monsignor Marquis in 1895–96 that became the site of parish pilgrimages and in the 1930s the “national sanctuary for devotion to saints’ relics.”

This foundation added further lustre to the career of Calixte Marquis, who was an enterprising man, blunt and colourful in his language, and who would leave his mark on religion, education, politics, and colonization. In 1889 Honoré Mercier*’s government recognized him when it invited him to collaborate with assistant commissioner François-Xavier-Antoine Labelle* in promoting colonization in the northern part of the Lac Saint-Jean region; the two priests worked especially at establishing some Trappists in the ecclesiastical district of Saint-Michel-de-Mistassini (Mistassini) who were to teach agriculture [see Pierre Oger*]. This was the last mission Marquis undertook. He lived more and more in isolation, as his many friendships with bishops came to an end through death or quarrels; he retained the affection and veneration of his former parishioners, however. This mixed regard was apparent at his funeral in December 1904, at which no titular member of the episcopate was to be seen in the large crowd, not even the new bishop of Nicolet, Hermann Brunault.

Calixte Marquis is the author of Mémoire sur la colonisation des terres incultes du Bas-Canada: pour être présenté à Nosseigneurs les évêques de la province ecclésiastique du Canada, réunis à Québec, à l’occasion de la consécration de Sa Grandeur Mgr. J. L. Langevin, évêque de Rimouski ([Québec], 1867) and Petit recueil de cantiques, à l’usage des missions, retraites, neuvaines et cathéchismes ([Trois-Rivières, (Qué.)], 1845; 2e éd., [Québec], 1863; 3e éd., [Trois-Rivières], 1889).

ANQ-Q, CE1-1, 14 oct. 1821. Arch. de l’Évêché de Trois-Rivières, Doc. relatifs à Mgr Calixte Marquis (en cours de classement). Arch. du Séminaire de Nicolet, Qué., C133 (Div. du diocèse de Trois-Rivières); F163 (Calixte Marquis). Archivio della Propaganda Fide (Rome), Scritture originali riferite nelle Congregazioni generali, vol.1021; Scritture riferite nei Congressi, America settentrionale, 15 (1877); 16 (1877a: Mgr Conroy); 17 (1877b: Mgr Conroy); 18 (1877c); 26 (1875–86). Can., Prov. of, Legislative Assembly, App. to the journals, 1857, app.47; Select committee on the colonization of wild lands in Lower Canada, Report ([Quebec], 1862); Special committee appointed to inquire into the causes which retard the settlement of the Eastern Townships of Lower Canada, Report (Toronto, 1851); Special committee on colonization, Report (Quebec, 1860). Georges Désilets, Le guide du pèlerin à la Tour des martyrs de Saint-Célestin, comté de Nicolet, P. Qué., Canada ([Annaville?, Qué.], 1932). Arthur Girard, La “Tour des martyrs” de Saint-Célestin, comté de Nicolet (Arthabaska, Qué., 1924). J.-E. Laforce, “Monseigneur Calixte Marquis, colonisateur . . . ,” CCHA Rapport, 11 (1943–44): 113–35. André Laganière, “Le missionnaire, un membre de la société,” Les Cahiers nicolétains (Nicolet), 4 (1982): 90–110; “Les missionnaires colonisateurs dans les Bois-Francs: 1840–1870” (thèse de ma, univ. du Québec à Montréal, 1979). Germain Lesage, Les origines des Sœurs de l’Assomption de la Sainte Vierge (Nicolet, 1957). Sœur Marie-Immaculée, “Monseigneur Joseph-Calixte Marquis et les Sœurs de l’Assomption de la Sainte Vierge,” CCHA Rapport, 11: 89–111. Michel Morin, “Calixte Marquis, 1821–1904” and “Calixte Marquis, missionnaire colonisateur du canton d’Aston (1850–1867),” Les Cahiers nicolétains, 3 (1981): 5–19 and 42–51; “Calixte Marquis, colonisateur des Cantons de l’Est, 1850–1870” (thèse de ma, univ. de Sherbrooke, Qué., 1980). Alphonse Roux, “Monseigneur Calixte Marquis et l’érection du diocèse de Nicolet,” CCHA Rapport, 11: 33–87. Jean Roy, “L’invention du pèlerinage de la Tour des martyrs de Saint-Célestin (1898–1930),” RHAF, 43 (1989–90): 487–507. Nive Voisine, “La création du diocèse de Nicolet (1885),” Les Cahiers nicolétains, 5 (1983): 3–41 and 6 (1984): 147–214; Louis-François Laflèche, deuxième évêque de Trois-Rivières (1 vol. paru, Saint-Hyacinthe, Qué., 1980– ).

Cite This Article

Nive Voisine, “MARQUIS, CALIXTE (baptized Joseph-Calixte Canac, dit Marquis),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 27, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/marquis_calixte_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/marquis_calixte_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Nive Voisine |

| Title of Article: | MARQUIS, CALIXTE (baptized Joseph-Calixte Canac, dit Marquis) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | February 27, 2026 |