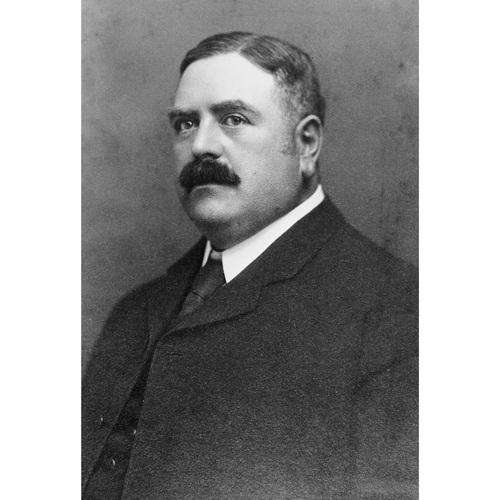

![Patrick J. (Paddy) Nolan, 1864-1913. [ca. 1910]. Image courtesy of Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta. Original title: Patrick J. (Paddy) Nolan, 1864-1913. [ca. 1910]. Image courtesy of Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta.](/bioimages/w600.11447.jpg)

Source: Link

NOLAN, PATRICK JAMES, lawyer; b. 3 March 1862 in Limerick (Republic of Ireland), son of James Nolan, a flour and feed merchant, and Mary O’Rourke; m. 19 April 1892 Mary Elizabeth (Minnie) Lee in Calgary, and they had one son, Henry Grattan; d. there 10 Feb. 1913 and was buried in Banff, Alta.

Paddy Nolan’s family tree included soldiers, bishops, poets, and a mid-19th-century American outlaw. He attended Sacred Heart College in Limerick, Trinity College in Dublin, and the University of London, receiving ba and llb degrees and a number of honours. Called to the Irish bar in 1885, he practised for four years in Dublin. Anti-English and an admirer of Daniel O’Connell, he became despondent over his country’s plight with the failure of the Home Rule Bill of 1886 and he emigrated in 1889. The choice of Calgary as a destination stemmed from a Limerick association with the Costello family, who had come to Calgary before him, but the relationship remains vague. One-quarter of Calgary’s population was Irish, and Nolan saw it as a “Little Dublin.” He was called to the bar of the North-West Territories within four weeks of his arrival, and became the junior partner of Thomas Brown Lafferty. Since Lafferty’s brother James D. was the mayor of Calgary, the partnership flourished in its early years.

Nolan, who played soccer, cricket, and billiards, had many social circles. These included in the city the Calgary Golf and Country Club, the Knights of Columbus, the Ranchmen’s Club, and the St Mary’s Club, as well as the Chinook Club of Lethbridge and the Macleod Club of Fort Macleod (where he established a branch office in 1896). He also enjoyed amateur theatre and operettas. He made his debut in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Trial by jury in 1890, acted as a comic in several plays from 1891, and helped organize the Calgary Literary and Debating Society and the Calgary Amateur Dramatic Club in 1892. That year he married Minnie Lee, who was considered one of the most beautiful young women in the city. Her social and cultural pursuits matched his, and she became active in St Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, and the Red Cross Society.

The young lawyer’s participation in the city’s public life was most notable in his first 15 years there: he was a founding member and the first secretary of the Calgary Board of Trade (1890–94), auditor of the city (1893–95), and editor of the Calgary Herald (1900–3). His participation was not, however, very successful. A useful example is his service as secretary of the Board of Trade. He did not participate in the annual meeting of 1891, and was frequently absent from the board by the autumn of 1894; in December that year its members required a motion to retrieve its charter and official papers from him. Nolan’s one pamphlet, The advantages of Alberta, a glossy and overdone eulogy, was written on behalf of the board in 1892.

A keen student of politics in his early years, Nolan ran in East Calgary for the Legislative Assembly of the North-West Territories in 1894, and was soundly defeated. Thereafter, he enjoyed giving speeches at political rallies, in the tradition of O’Connell, his Irish radical hero. Considering himself a spokesman for working people, he liked in particular addressing miners in the foothills, where he would take them a wagon full of liquor, and drink and talk into the night. His other major platform was as an after-dinner speaker and raconteur. Full of Irish stories, he kept his audiences in perpetual laughter. Since he was a favourite with newspaper associations, his speeches received a full press across the country. Perhaps his most famous speech was delivered to the annual meeting of the Knights of Columbus in New York City, which caused several papers to call him one of the best orators of the age.

Nolan seems to have lost his drive for both politics and law around 1901–2. This decline coincides with his 40th birthday, and with two interesting facts. In 1901 his close friend the politician and editor Nicholas Flood Davin*, also a native of County Limerick, committed suicide. The next year his other close friend, Robert Chambers Edwards*, left the editorship of the Wetaskiwin newspaper to found the Eye Opener in High River. Edwards, like Nolan, was a hard-drinking Catholic who lived for idle talk and laughter, and Nolan’s intemperance seems to have increased with Edwards’s move nearer to Calgary.

A pronounced individualist and extrovert, Nolan attracted unusual clients as well as uninhibited friends. Among those he defended were bootleggers, drunks, horse thieves, disorderly persons, and prostitutes. The stories of his keeping Caroline (“Mother”) Fulham, the famous Irish “pig-lady” of Angus (6th) Avenue, out of jail still occupy local legend. His best-known client, Ernest Cashel, was one of the region’s most notorious criminals. In several prosecutions Nolan defended the young man, until he was found guilty of murder and hanged in 1904. Not surprisingly, Nolan drew large crowds in court, and he delighted them with his antics, for he was a master of procedure, of people, of language. Judges as well enjoyed his humour. He prided himself on entering court with few if any papers. On one of the rare occasions when he litigated a major case before the Supreme Court of Alberta (The King v. Clarke in 1907–8), the opposing counsel, Richard Bedford Bennett*, entered the court-room with his assistant laden with books and called for his references: “Boy, give me Phipson on Evidence; Boy, give me Kenny on Crimes.” Nolan broke up the court when he uttered, “Boy, get me Bennett on Bologney.”

The records reveal that most of Nolan’s litigation was on the criminal side. Thus of the 23 cases in which he appeared before the local Supreme Court over 25 years, 14 were criminal cases. He was counsel for the accused in 11 cases, and lost 7 of them. Only when he began to prosecute in 1910–12, in order to make money, did he acquire a winning record (all three cases). Although he was counsel for few commercial organizations, he did some litigation for the Alberta government’s Beef Commission, the Veterinary Association of Alberta, and the Western Stock Growers’ Association. Most of these files, however, date from after 1907 when he was having financial difficulties. As a measure of his civil practice, only nine of his cases made the local Supreme Court, and seven occurred in 1908–11. He lost most of these as well. Since his criminal defence business was usually on behalf of the poor and the notorious, he was not well paid. In his small civil litigation he often represented renters, debtors, dismissed employees, and farmers.

Nolan has been hailed as one of the most successful criminal defence lawyers in Canadian history, and one of the two best orators in the history of western Canada. These claims, based largely on non-archival evidence, are questionable. Though contemporaries found Nolan’s rhetoric impressive, it is now difficult to judge its effect. As for his legal abilities, most lawyers of the pre-1914 era did not include him among the eminent lawyers of the time. When he was mentioned, it was more in the vein of John Edward Annand Macleod, who referred to Nolan and his partner Frank Ernest Eaton as “Eaton and Drinkin’.” Nolan’s career is mirrored in his association with local professional bodies. In early meetings of the Calgary Bar Association, of which he was a founder in 1890, he was active in moving motions from the floor. But after 1894 there is little mention of him in the minutes, apart from his attendance at the annual dinners through 1904 and at a few meetings in 1906. Admitted by the Law Society of Alberta as a bencher in 1907, the year he was made kc, he never sat on any committees or appeared at any meetings. Its records, however, show several complaints that his clients made against him from 1905.

Nolan’s drinking, often reported in the local press, became legendary. It must have accounted for his lack of business and commercial clients, as well as for his estrangement from his family. According to lawyer Ronald Martland, Nolan’s son Harry, who was appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1956 (he died the next year) “very seldom ever spoke of his father” because of the problems he had caused his mother, and was determined never to follow in his footsteps. Harry’s wife maintained that Paddy kept his wife short of cash and established no relationship with his son, even leaving his schoolboy letters unanswered.

Nolan died on 10 Feb. 1913, at the Ranchmen’s Club, having reached his 50th birthday. According to his biographer, he died “unexpectedly.” In fact, he died of a cerebral haemorrhage after a week of internal bleeding. What is his legacy? The standard biographical dictionaries, from Henry James Morgan to John Blue, give him a high place in the history of the law profession. The manuscript evidence, however, is less clear. Spellbinding as an orator, clever in court, and friend of the unknown and the undefended, Nolan left his mark on the frontier west in a way in which more notable lawyers would never have endeavoured to do.

GA, M1925; M2260, minutes and reports, 1 (1890–1913). Legal Arch. Soc. of Alberta (Calgary), F 5 (Law Soc. of Alberta fonds), vol.60, file 923: 141–42; F 60 (Law Soc. of the North-West Territories fonds), vol.1, file 1: 5, no.77; 93–94, 111–12 (photocopies). PAA, 69.305. Calgary Herald, 13 Feb. 1913. Morning Albertan (Calgary), 11 Feb. 1913. Alberta Law Reports (Toronto), vols.1–4. John Blue, Alberta, past and present, historical and biographical (3v., Chicago, 1924). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). [J. W.] G. MacEwan, “Eye Opener” Bob: the story of Bob Edwards (Edmonton, 1957); He left them laughing when he said good-bye: the life and times of frontier lawyer Paddy Nolan (Saskatoon, 1987). Territories Law Reports (Toronto), vols.1–7.

Cite This Article

Louis A. Knafla, “NOLAN, PATRICK JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nolan_patrick_james_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nolan_patrick_james_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Louis A. Knafla |

| Title of Article: | NOLAN, PATRICK JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |