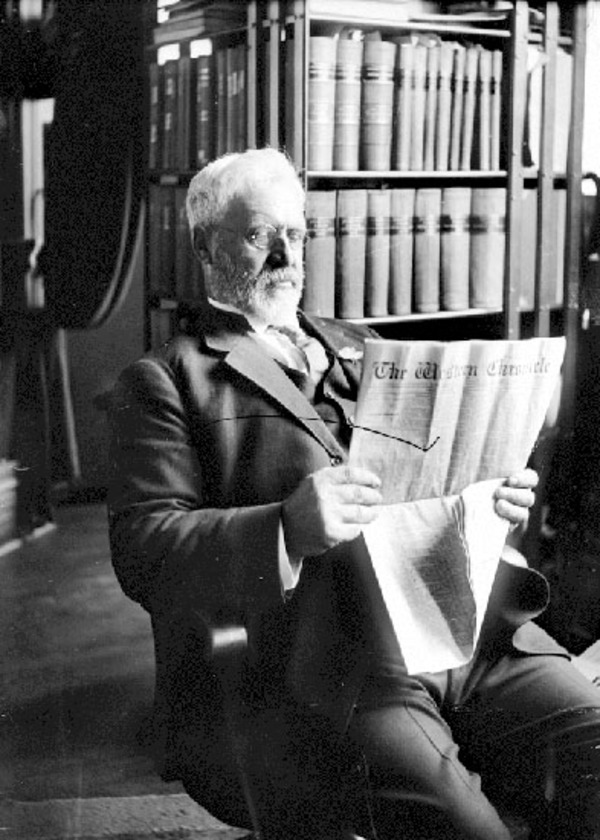

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

OLIVER, JOHN, farmer, office holder, and politician; b. 31 July 1856 in Hartington, England, son of Robert Oliver and Emma Lomas, a widow; m. 20 June 1886 Elizabeth Woodward in Mud Bay, B.C., and they had five sons and three daughters; d. 17 Aug. 1927 in Victoria.

The eldest of Robert and Emma Oliver’s eight children (his mother had a son from her first marriage), John Oliver grew up in an English farming community, where his family eked out a modest living. He left school at age 11 to work in a local lead mine. A few years later, when the mine closed, the Oliver family emigrated to Canada, settling on a farm in Maryborough Township, Ont., in 1870. Five years after their arrival, Emma Oliver contracted rheumatic fever and died. Her death evidently had a significant impact on the family, since members soon began to leave the farm. John stayed in the vicinity for over a year before deciding, at age 20, to travel west. On 5 May 1877 he arrived in Victoria, looking for work. He found it on the mainland of British Columbia with a survey crew of the Canadian Pacific Railway. After a summer of hard labour, he had saved enough money to start a farm, so he pre-empted land in Surrey.

While building a cabin and clearing land, Oliver was drawn to community affairs. He helped to establish a rural school and he petitioned the provincial government for assistance with roads in the recently settled district. At age 26 he was appointed clerk of the municipality; he also served as tax collector and general functionary. In the fall of 1882 he resigned his positions, sold his land, and purchased a farm in Delta. Four years later he married Elizabeth Woodward, a daughter of the local postmaster. They would raise five sons and three daughters, while developing one of the most prosperous farms in the region. Oliver also earnestly applied himself to municipal affairs in Delta. He became a school trustee and a few years later he was elected to the municipal council; he served two terms as reeve.

Although Oliver loved rural life, he had set his sights on higher public office. At age 43, he took a long-contemplated step into provincial politics by running in the election of June 1900. At the time, politics in British Columbia were characterized by intense factionalism and the absence of formal parties. On 28 February Joseph Martin had assumed the premiership, though with little support. Surprisingly, Oliver threw his lot in with Martin’s forces and campaigned aggressively in Westminster-Delta. On 9 June the Martinites went down to a crushing defeat, electing only 6 members to a house of 38. Oliver experienced his first important political triumph, however, winning in his riding.

Oliver’s introduction to the rough-and-tumble of British Columbia politics was neither kind nor gentle. A plain-spoken, rough-hewn man, he was derided as a hayseed by the more urbane and experienced members of the assembly. His unsophisticated clothes, heavy boots, and often crude use of the English language were lampooned by opponents. The Victoria Week described him in 1905 as “a good farmer and a weak politician, given to long-winded and very ungrammatical attacks upon anyone who does not agree with him.” This criticism did not dampen his spirits; rather, he became even more determined to show that an ordinary man could make a contribution to the democratic process. He studied parliamentary procedure and, over time, he made the transition from municipal to provincial politics, carefully choosing the causes that he championed in the assembly.

During the first decade of the 20th century the province moved towards formal adoption of the party system. By aligning himself with Martin, Oliver had identified himself as a Liberal, in opposition to the government of millionaire coalminer James Dunsmuir*, which was Conservative in all but name. Certainly, Oliver was an anti-establishment figure, yet his own brand of liberalism was shaped by his rural conservative roots. He earned the nickname Honest John for his principled pursuit of a legislative inquiry in 1902–3 into railway land grants that helped to bring down the government of Dunsmuir’s successor, Edward Gawler Prior, in June 1903. Richard McBride*, who formed the next government, immediately called an election and announced that it would be the first in British Columbia to be fought along party lines. Even though Oliver had had a falling-out with Martin, there was little doubt that he would campaign as a Liberal. On 3 Oct. 1903 he was returned in Delta with an increased majority. He would serve as part of the Liberal opposition led by James Alexander Macdonald*. McBride became the first premier in British Columbia to hold office under the Conservative banner.

While a member of the opposition, Oliver developed a reputation as a forceful politician. A colourful and folksy figure, he took great pride in his increasing comfort as an mla and as the opposition’s watchdog. Meanwhile, McBride, who held office during a period of economic growth, increased his popularity. His Conservatives were handily re-elected in the provincial election of 2 Feb. 1907. Once again Oliver retained Delta. The Liberal opposition was dispirited by McBride’s triumph and lacked the resources to hold a popular government accountable. Even more discouraging was the failure of the federal Liberals to offer any help. In desperation Oliver wrote to Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* in June 1909, stating that the provincial Liberal party “would much prefer to fight than to lie down but . . . the latter course appears to be the only one open to us.” Oliver sought visits from federal cabinet ministers and, most of all, newspapers with a Liberal bias. “We have an unscrupulous government with a large amount of money at their disposal and with full control of eighty per cent of the newspapers of the Province with an organization in full working order.” Laurier responded, but only with words of encouragement, counselling that “it would be a mistake to lose heart.”

In the fall of 1909 Macdonald was appointed to the bench, creating a vacancy in the position of provincial Liberal leader. Oliver had emerged as his chief lieutenant and was the obvious choice for the uncoveted post. Reluctant to assume the position, he told Laurier, who had encouraged him to seek the job, that “it is not a desirable thing to fall heir to at this juncture with the prospect of going into a fight crippled and almost helpless.” Nevertheless, mounting pressure and the absence of any other candidate compelled him to reconsider. He became leader with insufficient time to prepare for the general election, called for 25 Nov. 1909. A vociferous critic of the government’s railway policy, he decided to make it the centrepiece of his campaign. He disapproved of the recently negotiated contract with the Canadian Northern Railway for a line from the Alberta border to Vancouver, arguing that the province was not obliged to assist a private railway and that the details of the contract should have been made public before the election.

The Conservatives, who waged an aggressive campaign, won 38 of the 42 seats. They would face an opposition of two Liberals, Harlan Carey Brewster* and John Jardine, and two Socialists, James Hurst Hawthornthwaite and Parker Williams. For the first time in almost a decade, Oliver would not sit in the legislature; he lost in the two ridings he had contested, Delta and Victoria. There were reports that $60,000 had been spent to defeat him. Of course, Oliver had not expected to dislodge the Conservatives, but neither had he anticipated a rout and a personal defeat. The day after the election he declared that he was “out of politics for good.” As the drubbing was absorbed, however, it was clear that he had not lost his passion for public life. Initially, he returned to his farm and to local affairs in Delta; he was elected a school trustee and later served again as reeve. In the federal election of 1911 he stood as a Liberal in New Westminster. He went down to defeat with the Laurier government.

Early in 1912 McBride called a provincial election. With increased public revenues and little opposition, the Conservatives were poised for another easy victory. In fact, the incumbent in Delta, Conservative Francis James Anderson Mackenzie, pointed to the government’s plan to spend $85,000 on public works in the constituency during the forthcoming year, as opposed to the mere $15,000 that had been spent in the last year that Oliver represented the riding. On 28 March 1912 Oliver suffered another political setback and the Liberal party was completely shut out of the legislature. It was difficult to believe that there was a future for the Liberal party in the province. Oliver’s political career and dreams of higher public office were seemingly finished.

Within a few years, and after more than a decade in office, the Conservatives started to run out of steam. The provincial economy was unable to sustain rapid levels of growth and headed into a recession as World War I broke out. More troubling for the provincial government were the charges of corruption levelled at it. On 15 Dec. 1915 McBride surprised many by resigning the premiership. He was replaced by the energetic but dour William John Bowser*, who would preside over a sinking ship. In the spring of 1916 two Liberals, including Brewster, the new party leader, won by-elections. When Bowser took his flagging Tories to the polls late in the summer he faced a more organized Liberal party with some new, reformist ideas. On 14 Sept. 1916 Oliver was successful in Dewdney as part of an impressive electoral victory; 36 Liberals, 9 Conservatives, and 2 independents were chosen. The Liberals began a quarter century in which they would be the dominant force in British Columbia’s politics.

Oliver was appointed by Brewster, the new premier, to two cabinet positions, agriculture and railways, on 29 November. In both portfolios he applied himself keenly, inspired by the reforming impulse associated with the Liberal victory. Agriculture was a natural choice for him. He took great pride in his understanding of the challenges faced by farmers and he believed that a strong agricultural sector was vital to the province’s future. He also concerned himself with the soldiers who would return from the war and wanted to ensure that they would have the opportunity to own and develop farms in rural areas of the province. “Thinking over these problems in the night,” wrote his biographer, “an idea occurred to him. He got out of bed, and sitting in his nightshirt . . . he drew up the ‘Land Settlement [and Development] Act.’” This landmark legislation, passed in 1917, would be dubbed the “nightshirt” act. Oliver successfully urged the federal government to establish a national policy for the settlement of returning soldiers.

The railway portfolio allowed Oliver to pursue one of his abiding political interests, railway subsidies. His most pressing concern was the fate of the troubled Pacific Great Eastern Railway, a privately promoted scheme closely associated with the Conservative government. The PGER had never fulfilled its objective of establishing a north-south line to serve the province. At one point Oliver went so far as to proclaim in the legislature that he was “not going to become the foster-father of this illegitimate offspring of two unnatural parents. It was a waif left on my doorstep. It was conceived in the sin of political necessity; it was begotten in the iniquity of a half-million dollar campaign fund. I refuse to be the godfather of any such foundling.” Despite the declaration, Oliver initiated an investigation into the railway’s finances and negotiated its purchase. The criticism he received from the press for his actions made him extremely indignant. He had never evinced a great fondness for the line and he claimed to have “sweat blood” in order to achieve the best possible terms for the province.

Oliver had already established himself as one of Brewster’s chief lieutenants when the premier died on 1 March 1918. In the party caucus that followed four days later, Oliver was elected leader of the Liberal party and on 6 March he became premier. He would hold the reins of power, in his distinctively rustic fashion, for almost a decade. He was to retain the agriculture portfolio until April 1918 and the railway portfolio until October 1922. He chose a number of competent ministers to serve in his cabinet; three of them, John Duncan MacLean*, Thomas Dufferin Pattullo*, and John Hart*, would later serve as premiers.

British Columbians seemed comforted by their new, plain-spoken premier, whose personal habits were largely unaffected by the trappings of office. Oliver continued to wear the same old-fashioned tweed suits and heavy boots that had become his trade marks. “Doff your broadcloth and don your overalls,” he instructed a large delegation from the province’s municipalities soon after assuming office, urging them to assume responsibility for their overspending. He portrayed himself as a man of the people, distrustful of experts and wholly lacking in pretence. This populist style of politics would be his strength and it had great appeal in a province that had grown apprehensive about its future.

When Oliver became premier, World War I was coming to an end. Over the next few years, instead of accepting the government’s programs to develop farms, veterans poured into the province’s urban and industrial centres. The new premier was sadly disappointed with this result. His government had attempted to deal with the challenges anticipated in the post-war period by introducing social legislation that limited work to an eight-hour day in certain industries, improved working conditions, and provided a minimum wage for women. It moved as well to establish mothers’ pensions in 1920, provide maintenance for deserted wives, and improve both health and educational services. Legislation to regulate public utilities and impose controls on the forest industry was also passed. All of these initiatives were based on the belief that direct government intervention was the best way to deal with the problems that beset the province.

The bright burst of reform was insufficient to quell social and economic turmoil, however. To Oliver’s chagrin, farmers were agitating against the government, having formed their own political party, the United Farmers of British Columbia, in 1917. The first years of Oliver’s premiership were also ones of labour militancy; many workers struck in sympathy with those involved in the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 [see Mike Sokolowiski*]. In addition to these troubles, the premier acquired some notoriety in the libel case concerning the Dolly Varden mine when he sued the mining company’s lawyer for suggesting that he was involved in private land speculation. He eventually won, but was awarded only a token amount in damages. The court decided that Honest John had neither lost his reputation nor suffered from the accusation.

Oliver’s leadership of the Liberal party was the subject of criticism. Some Liberals argued that he should have promptly submitted his selection as party leader to the electorate for endorsement. In June 1920 he responded to this pressure, calling an election for 1 December. Women would be casting ballots for the first time in British Columbia and Oliver had been advised that an earlier date in the autumn would be inconvenient for them because it coincided with church fairs and the making of preserves. As it turned out, he had more to worry about than the newly enfranchised women. His government was under attack from resurgent Conservatives and an array of parties and candidates representing labour, farmers, and veterans. His election manifesto asked voters to let the Liberals continue their “safe, sane and progressive administration.” The premier focused his campaign on the building of roads to open up the rural areas of the province – a theme that would become a constant feature of politics in British Columbia for the next half century.

The Oliver government barely survived, winning a slim majority, 25 seats out of 47. Under Bowser’s aggressive leadership, the Conservatives won 15 seats. Joining them in opposition was a motley group of Labour and independent members. The Liberals’ support came primarily from the urban centres. Oliver, who had won in both Delta and Victoria, chose to represent the capital. The election of 1920 signalled a shift in direction for the Liberal government. The hard-fought campaign had been won by Oliver largely because of the fragmented opposition. Entering a new decade with a tenuous grip on power, he was forced to contend with dissent within his party. Although his cabinet boasted a number of strong ministers, he was criticized as “bossy” and was inclined to function as a one-man government. He suffered resignations, including, in November 1921 that of Mary Ellen Smith [Spear*], the first woman elected to the assembly, and in 1924 that of his finance minister, Hart. The premier fought the Vancouver Liberals’ audible mutterings that “Oliver must go.” The younger, more urbane forces in the party were clearly tiring of their grandfatherly farmer-premier.

In this hostile environment, Oliver retreated into a careful, almost tentative, mode of governance. The reform impulse associated with the Brewster-Oliver administration dwindled. The 1920s were an economically uncertain decade. Oliver grew even more cautious when it became evident that revenue from resource industries such as forestry could not be counted on to support an expensive agenda of social initiatives. The premier’s enthusiasm for reform also diminished because the external challenges to his government increasingly came from the right wing of the political spectrum and from the business community. This situation was highlighted by the formation of a new political force in 1923. Led by Vancouver millionaire Major-General Alexander Duncan McRae* and by Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper, the Provincial party called for an end to waste in government and the termination of the party system; its interests were those of big business, not the disadvantaged of society. In many other ways the business community expressed its lack of support for the Oliver government. For instance, through 1923 and 1924 the forest industry waged a public battle with the government over its proposals to raise the royalties charged to forest companies. The Timber Industries Council, a powerful lobby group, was eventually able to persuade it to back away from this initiative.

Among the numerous issues that beset Oliver was the liquor question. Through a referendum on 20 Oct. 1920, the province had rejected Prohibition in favour of government-controlled sale of alcohol, although this solution was controversial even within the Liberal party. For example, in 1921 Liberal mla Henry George Thomas Perry objected to the government profiting from the sale of alcohol, warning that “British Columbia should not become a second Monte Carlo, or the Premier of the Province another Prince of Monaco.” The Government Liquor Act, adopted later that year, provided for the sale of alcoholic beverages in government stores, which became known as John Oliver’s drug stores, but not in bars or saloons.

The premier managed to keep his party under control and shrugged off the attacks of the combined opposition forces, but his government’s prospects appeared bleaker as his term wore on. He had hoped that the return of a Liberal government to Ottawa in 1921, under William Lyon Mackenzie King*, would assist his beleaguered administration. The federal Conservatives had granted scant consideration to his pleas for revisions to railway freight rates. King, although sympathetic, provided little in the way of practical benefit. As Oliver began to contemplate the discomfort of another provincial election campaign, he bravely reported to King, “I am optimistic and if I have to go down, I will go down fighting and with the flag flying.”

The lack of favourable reaction from the new Liberal government in Ottawa, combined with intense pressures at home, produced in Oliver the new battle cry “Fight Ottawa.” Since the federal government would not assist British Columbia with helpful railway policies or better terms on a range of other issues, Oliver increasingly gave vent to strong words on provincial rights. In moments of sheer frustration, he even went so far as to question his citizenship. “I have never advocated separation, but if the grossly unjust treatment Western Canada is subjected to in favour of Eastern Interests is to be continued indefinitely, then I do not want to call myself a Canadian.”

Oliver took this aggressive posture into the provincial election, called for 20 June 1924. It was a bitterly fought contest. Voters were confused and so were the results. After a number of recounts it became clear that the leaders of all three major parties, including Oliver, had been defeated. The Liberals won 23 seats, the Conservatives 17. The Provincial and Labour parties each elected three members and the house would include two independent mlas as well. With the support of less than a third of the electorate, the Liberals could form a minority government, but the two right-of-centre parties combined had received nearly 54 per cent of the votes cast.

Believing his leadership had provided the key to the Liberal party’s bare survival, Oliver stayed on. He won a by-election in Nelson on 23 August and governed by a fragile thread with the support of independent and Labour members of the house. It was hardly a situation to produce vigorous government; in fact, the reform impulse completely faded away. The premier tried to invigorate his party by launching another campaign for lower freight rates. In 1925 he was able to secure a reduction in the rate for grain. This victory enabled him to assist the Liberals in the federal election of 1926. When the Liberal representation from British Columbia in the House of Commons dropped from three in 1925 to one in 1926, it left the premier “very blue.”

An improving economy made the last part of the decade somewhat sweeter. Oliver continued his efforts to move construction of the PGER forward against opposition charges of incompetence and corruption, and he survived the royal commission re campaign funds, an investigation in 1927 into allegations that liquor interests had funnelled contributions to the Liberals. In spite of continuing challenges from within his party, he firmly held the reins of leadership. In 1926 he had celebrated his 70th birthday; he was the oldest government leader in Canada. The last session of the legislature with Oliver as premier, which ended on 7 March 1927, was marked by the passage of the Old-age Pension Act. The premier considered it to be among the most important pieces of legislation he had sponsored. In addition to promoting the measure, his party adopted a new program for reform that year, marking a return to the concern for social issues that had characterized Oliver’s first mandate. His final year as premier was notably busy. He travelled to Ottawa to lobby the federal government once again on railway issues. He also toured the interior of the province, attending various ceremonies. These activities seemed to take their toll. After he fell ill, his doctors sent him in May 1927 to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., where an exploratory operation determined that he had incurable cancer.

John Oliver returned to British Columbia and called a caucus meeting in July, during which he tearfully offered his resignation as party leader and premier. His colleagues refused to accept it, urging him stay on. He agreed, but only on the condition that J. D. MacLean, his long-time lieutenant, be named premier designate. Oliver died in Victoria, aged 71. He lay in state in the legislative chamber that he had dominated for so many years and was given an official funeral. A populist political leader, he had strengthened and consolidated the provincial Liberal party and established a folksy, yet combative style of leadership that would be emulated by British Columbia premiers for generations to come.

LAC, MG 26, G; J. Brief record of the Oliver government ([Victoria], 1920). Electoral hist. of B.C. Robin Fisher and David Mitchell, “Patterns of provincial politics since 1916,” in The Pacific province: a history of British Columbia, ed. H. J. M. Johnston (Vancouver and Toronto, 1996), 254–72. S. W. Jackman, Portraits of the premiers: an informal history of British Columbia (Sydney, B.C., 1969). James Morton, Honest John Oliver: the life story of the Honourable John Oliver, premier of British Columbia, 1918–1927 (London, 1933). M. A. Ormsby, British Columbia: a history ([Toronto], 1958). Martin Robin, The rush for spoils: the company province, 1871–1933 (Toronto, 1972).

Cite This Article

DAVID MITCHELL, “OLIVER, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 27, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/oliver_john_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/oliver_john_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | DAVID MITCHELL |

| Title of Article: | OLIVER, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | February 27, 2026 |